In Booming Brooklyn, Who’s Getting Left Behind?

The borough outpaces the city in creating new jobs, but statistics show the persistence of Central Brooklyn's misery

Construction workers on the job at 280 Cadman Plaza West, which will be a 36-story condo tower. Last year, the construction sector of Brooklyn's economy was responsible for a record 32,100 jobs with an average salary of $60,000, according to a state report (Photo by Steve Koepp; graphics by Heather Jones)

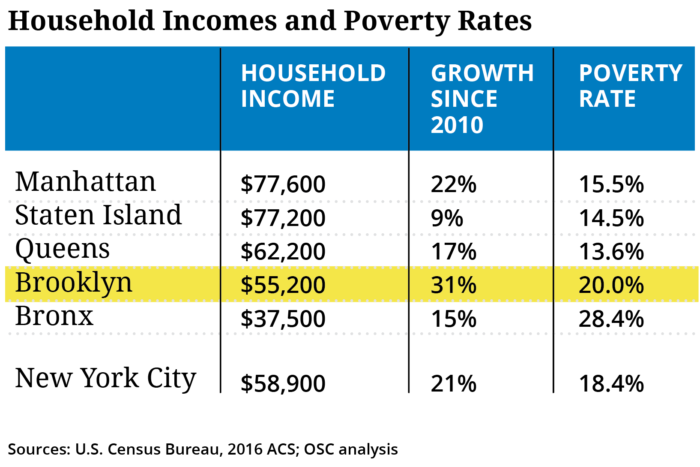

Brooklyn has the fastest income growth of any borough in the city–and the second-lowest household income. Its unemployment rate is the lowest in decades, but one in five of its households still lives below the poverty line. No other borough has added as many businesses in recent years, yet its businesses pay the lowest average salary in the city.

Overall, economic times are great in the County of Kings, but many of its residents have been left out of the staggering growth that has transformed the borough, according to a report released recently by the state comptroller’s office.

The report is a highlight reel of prosperity. To start with, the borough’s rate of job growth (4.4% last year) is faster than the pace of the city, state and the U.S. as a whole, said comptroller Thomas DiNapoli in a statement announcing the report.

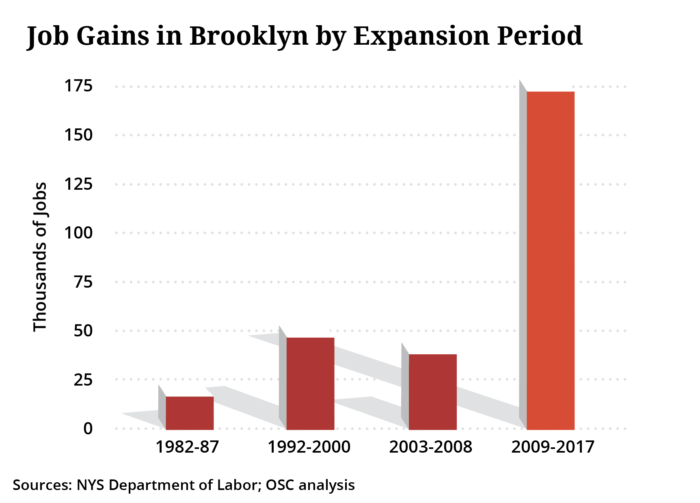

What’s more, Brooklyn’s growth hasn’t had to make up for huge numbers of jobs lost in the Great Recession. The borough lost 1,400 jobs overall, but since 2009, the year the recession ended, Brooklyn has added 172,600 private-sector jobs, which is nearly four times as many jobs added during the last big expansion in the 1990s.

Jonathan Bowles, executive director of the Center for an Urban Future, a New York City think tank, used a non-technical term to sum it all up. “Brooklyn,” he told The Bridge, “is really crushing it when it comes to economic growth.”

More People, More Jobs

Several factors could be driving that growth, he said. For one, the borough has become much better educated. In 2000, about one in five residents had a college degree or more, according to the report, while today one in every three residents does. Highly educated people have been migrating into the borough, said Bowles, in a pattern that Manhattan has previously benefitted from.

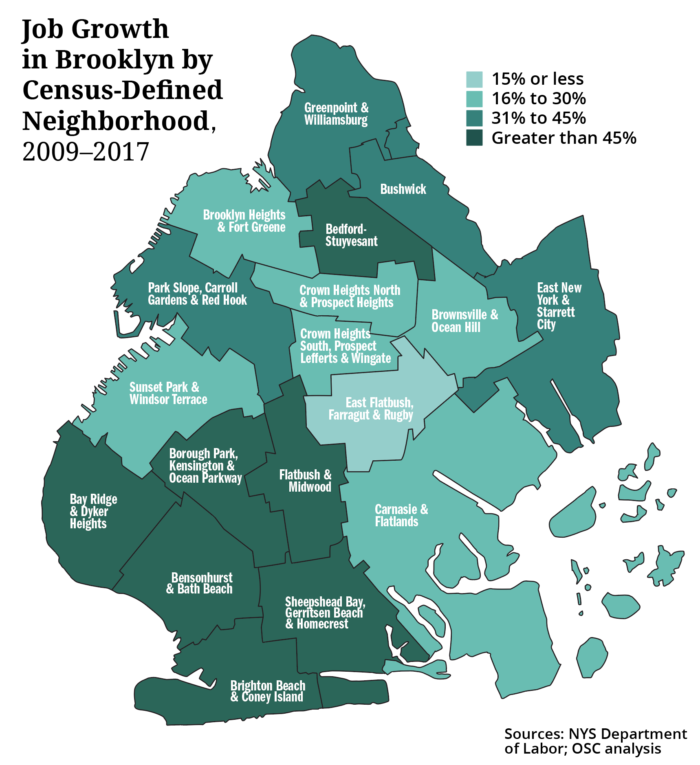

Brooklyn’s population growth–a 19% gain since 1980, to 2.6 million–may have also propelled job growth by boosting local demand for goods and services. Jobs have grown fastest in an area that extends from Flatbush to Bay Ridge and stretches southward to Brighton Beach, according to the comptroller’s report.

Population growth and aging of the population in those areas–the fastest-growing segment of Brooklyn’s population in recent years has been between the ages of 55 and 64–has created the demand for health-care jobs at hospitals, community clinics and urgent-care centers. Health care has led growth across the entire borough, Bowles noted, and “doesn’t get as much attention as it probably deserves.” The sector is the largest employer in Brooklyn, with 149,100 jobs last year, a 54% increase since 2009.

Retail jobs have grown swiftly as well, up 36% since 2009, to 77,100 last year. What’s most dramatic in the last two decades, however, is that Brooklyn’s economy has diversified beyond traditional industries to include so-called creative jobs including tech and design positions, often filled by the highly educated newcomers from outside the borough. Tech jobs in particular tend to be highly paid, with an average salary of $92,900.

Brooklyn has become a tourist destination as well, attracting an estimated 15 million visitors a year, who spent $2.1 billion in 2016. To accommodate them, 64 new hotels have been built in the borough since 2009 and the leisure-and-hospitality sector’s payroll more than doubled, adding 30,100 jobs, according to the comptroller’s report.

While traditional, large-scale manufacturing has declined in Brooklyn, smaller-scale operations have mushroomed at repurposed and expanded industrial centers including the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Brooklyn Army Terminal. Food-and-beverage manufacturing has grown 31% since 2009, to 7,300 jobs, the state report said.

“We Have Much More to Do”

While median household income in Brooklyn rose 31% since 2010, faster than in any other borough, it had a lot of catching up to do. Brooklyn’s household income of $55,200 still lags behind every borough except the Bronx. Last year, average private-sector salaries ranked dead last, at $42,500, even after a 55% jump since 2009.

What those averages betray is the persistence of dire poverty and joblessness in Central Brooklyn neighborhoods including Brownsville, Ocean Hill, East New York and parts of Bedford-Stuyvesant.

In Brownsville and Ocean Hill, nearly 36% of households had income below the federal poverty line in 2016, the state reported. In Brownsville, the most recent unemployment rate is 14%, more than three times the city’s average, according to figures from the New York University Furman Center.

Residents in the Brownsville/Ocean Hill area have the shortest life expectancy of any community district in the city, at 76.7 years, a 13-year difference from the longest-lived neighborhood of Bayside, Queens, according to a statistical portrait of the city.

Said Borough President Eric Adams said in a statement accompanying the comptroller’s report: “While we have done a lot to come back from the Great Recession, we have much more to do, particularly in areas such as communities in central and eastern Brooklyn to combat the deep roots of inequality and poverty.”

“We have had such success in urban revival that New York City has become a place rich people from around the world want to live,” Richard Florida, a professor and director of cities at the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, told the New York Times last month. “So now we have to deal with the hard problem of persistent poverty, which remains in largely minority neighborhoods.”

Solutions and Risks

Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio have both launched sweeping programs to boost employment and quality of life in the city’s disadvantaged neighborhoods, though the results will take years to bear fruit.

Cuomo appeared in Bedford-Stuyvesant in April to provide an update on his $1.4 billion program, called Vital Brooklyn, to boost the borough’s central neighborhoods in eight different ways, including job creation, health care, affordable housing and parks. The governor announced five requests-for-proposals (RFPs) to build more than 2,000 affordable homes. Among the myriad features of Cuomo’s plan is an allocation of $325,000 to open 12 new, youth-run farmers markets to teach kids about entrepreneurship and healthy foods.

Mayor de Blasio, for his part, launched a $1.5 billion program last year, called New York Works, aimed at creating 100,000 jobs paying $50,000 or more over the next decade. But there is concern among elected officials in poor and working-class neighborhoods that the bulk of the new jobs won’t be accessible to their residents.

On the borough level, Adams has helped connect K-12 schools to CUNY institutions for job training, and has provided funding for business incubators for industries including advanced technology, life sciences, and fashion and design.

Business is picking up dramatically along the Fulton Mall, where new developments like City Point have drawn shoppers from neighborhoods all over Brooklyn (Photo by Crary Pullen)

City government is trying to do its part to get jobs to those who don’t have them. Workforce1 is a program of the city’s Department of Small Business Services (SBS) that prepares residents for jobs and matches employers with candidates. A spokeswoman said SBS connects at least 25,000 people to jobs each year, a fourth of whom live in Brooklyn. Last year, one of Workforce1’s largest sources of jobs was the live-entertainment company AEG, which hired ushers, lobby attendants, and others to help the company staff Barclays Center.

Increasingly, though, boosting employment levels will require more spending and innovation in education, said Bowles, the think-tank director. To lift up neighborhoods like East New York and Brownsville, more investment in education should focus on creating pipelines into well-paying jobs, he said. Brooklyn has assets that could be called upon, including 18 college-level institutions, which have been developing specialized programs aimed at fast-growing sectors ranging from hospitality to cyber-security.

Another way to stimulate employment would be to help keep Brooklyn’s small-business juggernaut rolling. The borough had a total of 61,300 businesses last year, an increase of 32% since 2009, almost double the citywide growth rate, the state reported.

At a rally at City Hall last week, Council Member Mark Gjonaj said that helping small entrepreneurs in the city could be best achieved by lowering their taxes and fees. Gjonaj (pronounced “Joe-nye”), who represents a Bronx district and chairs the council’s Small Business Committee, introduced a bill after the rally that would identify locally owned businesses with fewer than 10 employees and use that count of so-called micro-businesses “so that we can develop solutions that are specific to their needs,” he said, as reported in The Villager.

Advocates for small-business tenants have proposed another solution: the Small Business Jobs and Survival Act (SBJSA), which has been kicking around the council for more than three decades. The advocacy group TakeBackNYC says on its website that the SBJSA would give tenants “[a] minimum 10-year lease with the right to renewal, so they can better plan for the future of their business.” Asked by The Villager whether he supports the legislation as proposed by advocates, Gjonaj responded, “We’re going to look at it.” Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez, who represents uptown Manhattan neighborhoods, re-introduced the bill in March, and Gjonaj said a hearing would be held in July.

There’s another challenge to the borough’s future prosperity, one that is largely out of the city’s control. President Trump’s immigration policies could depress the number of people who move to New York City from other countries.

While local sanctuary policies may have blunted the effects of the crackdown on undocumented workers by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the President’s policies have diminished legal immigration as well. The number of people receiving visas to move permanently to the U.S. is on pace to drop 12% in Trump’s first two years in office, according to a Washington Post analysis of State Department data.

Foreign-born residents make up 36% of Brooklyn’s population, one of the highest components of any county in the U.S., but they have an even larger role in the economy. Immigrants make up 48% of the work force and 57% of self-employed entrepreneurs, according to the comptroller’s report.

“There are few cities that would be hurt more” by restricting immigration than New York, said Bowles. In Brooklyn, he noted, “So much of the economic growth in recent years has in some way been driven by immigration.”