In a negotiation that went down to the wire—past the start of a scheduled City Council subcommittee hearing Thursday—months of debate over the scale of the ambitious two-tower 80 Flatbush project concluded with a compromise agreement for modest cuts in its height and bulk. The promised public benefits in the project—two schools and 200 units of affordable housing—will remain in place, according to the deal reached by City Council Member Stephen Levin (33rd District), Alloy Development, and city officials.

The mixed-use mega-project, which has been strenuously opposed by nearby residents as having unacceptably massive scale near low-rise blocks, was able to overcome resistance because of the popular momentum to maintain its proposed benefits and the emergence of a moderately smaller revision that the developers revealed this week.

The willingness of Alloy Development to accept a 12.5% cut in the project’s bulk suggests that the original rezoning proposal, made in partnership with the New York City Educational Construction Fund (ECF), called for a somewhat bigger project than necessary to cross-subsidize the public benefits.

Much of the debate has been over the project’s sheer heft—as measured by a metric called Floor Area Ratio (FAR), a measure of bulk as a multiple of a fully covered lot—and its attendant impacts on the area around it. The original proposal called for a FAR of 18, which is unprecedented in recent decades around Downtown Brooklyn and would have nearly tripled the bulk allowed by the site’s current zoning. Community Board 2 had almost unanimously rejected the original proposal in its advisory vote, without recommending any compromise.

A redesign of the project transfers bulk lower down, to a new pedestal structure at the corner of Third Avenue and Schermerhorn Street

Thus the deal marks a victory for 80 Flatbush proponents, given that the approved FAR is 15.75, even with a cut of some 137,000 sq. ft., involving office space and perhaps 30 of the 700 planned market-rate units, all in the larger tower.

Levin, who as the local representative has the key political voice on the project, had indicated a preference for a bigger cutback in the project. Earlier this year, he compared 80 Flatbush to a building that had won an FAR of 15, noting that the latter was more clearly located in Downtown Brooklyn. That suggested less bulk should be tolerated in the 80 Flatbush block, which transitions between broad Flatbush Avenue and row-house State Street (and is claimed by some as part of Boerum Hill). The other boundaries for the site, which is a block from the Atlantic Terminal transit hub, are Third Avenue and Schermerhorn Street.

The Council Member also seemingly endorsed the Boerum Hill Association’s (BHA) call for an FAR of 12, the zoning standard in the Central Business District, but earlier this week told the Brooklyn Paper, “I’d find it difficult to go above 15 FAR with the schools included.”

Originally, the taller tower would have stood between two historic buildings, leaving the project with a narrower base

He wound up bending a bit further, negotiating Wednesday night with Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen and checking in daily with Council Speaker Corey Johnson, as well as toggling between constituents and Alloy. “I think honestly it came down about as far as it could while still achieving all of the benefits that were proposed and still being a viable project,” Levin told The Bridge.

Scale and Design Changes

The taller tower, on Third Avenue, will be 840 feet, including the bulkhead, rather than 986 feet. It will still eclipse the tallest tower nearby, the Hub on the north side of Schermerhorn Street, which is 610 feet. Borough President Eric Adams had endorsed the Hub as a height cap, while essentially endorsing a similarly modest cut in bulk. (The buildings on the south side of Schermerhorn, which will include 80 Flatbush, are typically 140 feet.) A second, wedge-shaped tower, on Flatbush, will be trimmed from 561 feet to 510 feet.

A redesign of the project, with a new floating-pedestal structure over a historic building at the corner of Third and Schermerhorn streets, transfers bulk closer to the street. At the Subcommittee on Zoning & Franchises meeting Wednesday, the redesign was described by Chairperson Francisco Moya as lessening the impact of shadows on the nearby Rockwell Place Brooklyn Bear’s Community Garden, whose members have protested the projects.

Levin praised Alloy for responding to community concerns, such as agreeing to move the loading docks off State Street. He had even brought up the possibility of sacrificing two historic but not landmarked structures that will be incorporated into the project, but Alloy—run by architects—“said ‘We’d rather not,’” Levin recounted. (The approval of the deal by the full City Council is expected, culminating the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP, to allow the necessary rezoning.)

Behind the Deal

Some market-rate units in the first tower, expected by 2022, will pay for a new elementary school (with 164 net new seats, given 186 expected new students who will reside in the project) and a larger replacement for the on-site Khalil Gibran International Academy, also with 350 seats. Market-rate units in the second tower, expected by 2025, will cross-subsidize the permanently affordable low-income units in that building.

Two new schools on the site were a major selling point of the project

Alloy touted an estimated $230 million in public benefits from the project—the schools, affordable housing, and cultural space—with no spending by the city. However, the project has been marked by a lack of transparency regarding its financials. No neutral entity assessed how valuable the increased bulk allowed by the proposed rezoning would be to the developer. Moreover, an agreement between ECF and Alloy regarding rental terms, which could illuminate the balance between public and private benefit, was never made public, though Levin gained some access. “I don’t know if it’s actually finalized yet,” he said.

Alloy CEO Jared Della Valle, in a statement, thanked Levin “for his deep engagement on the issues and working tirelessly to help deliver a project and design that addresses community concerns without compromising the project’s essential benefits.” He also thanked neighborhood stakeholders, citing the Boerum Hill Association for “its respectful and constructive advocacy.”

The BHA, though, was not cheering the compromise. “From the beginning the BHA asked for one tower, a new high school, and affordable housing,” stated BHA President Howard Kolins. “We were always willing to be flexible so that the City could benefit, and the nearby community would have a say. This is a very mixed outcome. The City needs to revise the development process to allow meaningful community engagement so intelligent development can take place.”

The push for benefits from a project like 80 Flatbush was heightened by the unintended consequences of the 2004 Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, which was aimed to produce office space but instead triggering market-rate housing without sufficient schools. Those needs overrode the original purposes of the Special Downtown Brooklyn District, designated to create a transition between high-rise Downtown Brooklyn and the row houses of nearby neighborhoods like Boerum Hill. (A large building, more than 500 feet, could still have been built as-of-right, with no rezoning.)

“It’s not a transitional block, that’s the new reality, but it brings really significantly more benefit than any other development in Downtown Brooklyn,” Levin said.

While Della Valle said “it’s those benefits”—the schools and the affordable housing—“that led us to pursue this project in the first place,” presumably Alloy didn’t invest $80 million to acquire the private property on site as an act of charity. The land acquisition put Alloy—known for architecturally striking projects in DUMBO—in a unique position to respond to a Request for Expressions of Interest from the ECF, which controls the 23% of the block that’s publicly owned, to build a mixed-use project.

Tailwinds in Favor

The deal benefited from some significant tailwinds in favor of the project, and not just from the de Blasio Administration. A Daily News editorial backed the project as proposed, claiming that a diminished scale would torpedo the benefits. An op-ed in Crain’s New York Business suggested that the benefits “clearly outweigh the costs.”

Notably, architecture critic Alexandra Lange, a Cobble Hill resident writing in Curbed, acknowledged that “over the past two years I have become increasingly uncomfortable with my position” opposing increased density at another controversial project, the redevelopment of the Long Island College Hospital site. (The LICH site developers, unlike those at 80 Flatbush, decided to build as-of-right rather than a larger complex that included public benefits.)

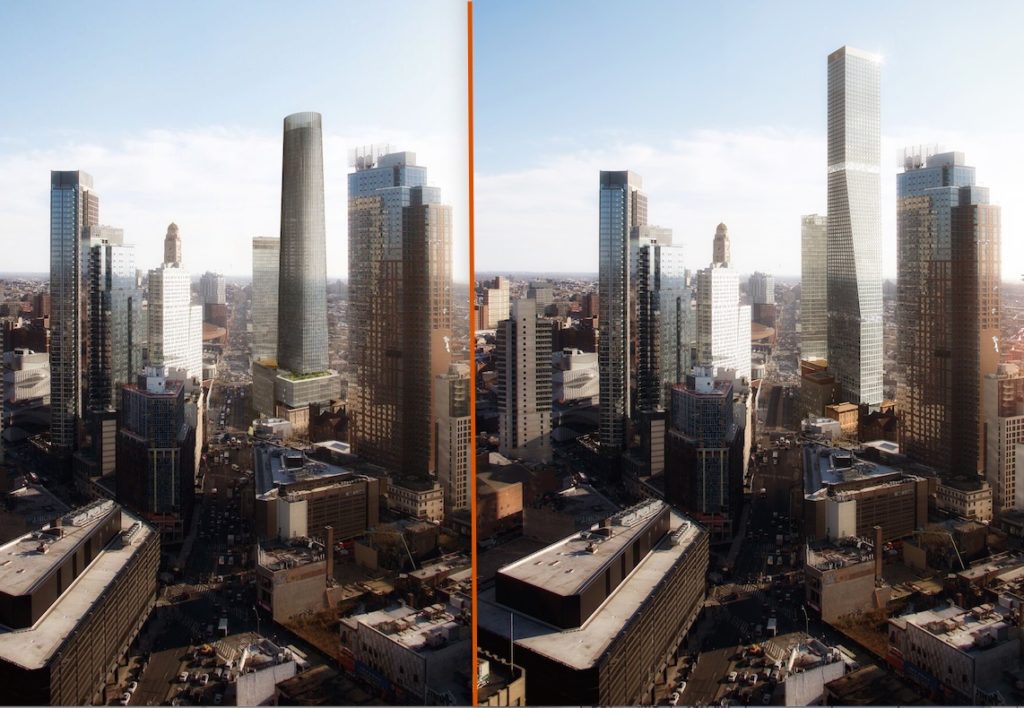

The smaller of the two towers, a wedged-shaped building in the foreground, has been cut by about 50 feet (left rendering), to about the same height of the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank building. (The previous version is at right.) The larger tower will be 840 feet, down from 986 feet. In the background, the supertall tower 9 DeKalb, currently under construction, will be 1,066 feet

Lange suggested the debate concerned “how a city as dense as New York should build its way out of a housing crisis and insufficient community facilities” and called a 80 Flatbush a “best-case scenario” for cross-subsidizing benefits, given “high-quality design, excellent public transit options, and a desirable neighborhood.”

Given that Alloy built some padding “into its opaque funding structure”—she cited The Bridge—Lange urged compromise not on density but benefits, such as support for parks and the pedestrian and transit experience. (The project gained support from transit advocates by eliminating parking facilities.) She contended that a FAR of 18 is “not out of scale for the avenue as it has developed.”

Is This Any Way to Review Big Projects?

Kolins’s statement about the need for “meaningful community engagement so intelligent development can take place” in some ways echoed Brooklyn Council Member Brad Lander’s comments this past Monday before the Council-spurred Charter Revision Commission 2019 that “our highly reactive ULURP process just is not getting the job done.”

“Each application is brought either by a private developer or by the administration, and it’s not judged against a broad set of goals we’ve collectively agreed to, for sustainability or affordability or how to share and distribute the challenges and benefits of growth,” Lander said.

“I don’t think it’s simple,” Lander said, citing a joke that “sometimes our whole land-use process is just REBNY [Real Estate Board of New York] versus NIMBY [Not In My Back Yard],” pitting “developers that want to see change happen, and people in their neighborhoods who feel that it’s going to erode or destroy what’s best about their neighborhoods. And we just shout it out. Right now we are not starting from a more comprehensive look at what challenges the city is facing.”

In this case, 80 Flatbush also got a general push from pro-development YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard) advocates and editorialists who believed that housing growth near mass transit trumped other concerns. Said Alloy’s Della Valle in the firm’s statement: “We hope the broad support we received for building a dense project in a transit-rich area sends a strong message across the five boroughs: amid an ongoing housing crisis, New York City needs to be progressive and seize every opportunity for growth in locations that can accommodate it.”