Amazon Next Door: What Does It Mean for Brooklyn?

The multibillion-dollar investment will have an impact on jobs, housing, transportation and more

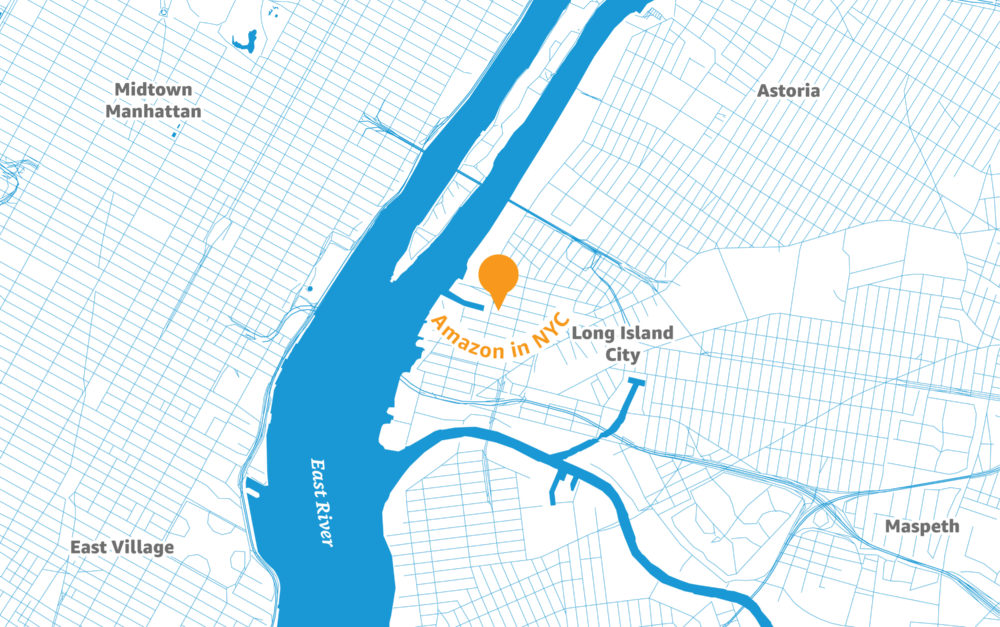

Amazon's planned Long Island City campus will be just north of the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Greenpoint and Williamsburg (Map courtesy of Amazon)

Since Amazon announced that half of its second headquarters is coming to Long Island City—with the other half landing in Crystal City, Va.—opinions on the development ranging from jubilant to outraged have flooded the zeitgeist. In Queens, the news has raised concerns about everything from the state’s generous tax incentives to rising housing costs to overcrowded transit systems.

As early as next year, Amazon will occupy up to 500,000 sq. ft. of office space in the 50-story tower at One Court Square in Long Island City, while working to develop 4 million sq. ft. of commercial space on the nearby waterfront over the next decade, and possibly much more in the years beyond, according to the New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYCEDC).

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo, often at odds, showed rare agreeability in cutting the deal. “We’re building a New York that’s attracting the industries of tomorrow,” read a tweet from the governor. “My thanks to @NYCMayor and our partners in the city for their help in this transformative investment in Queens.”

But what the mayor and governor hailed as a blessing was seen as a burden by many local officials, who felt the deal was imposed on them without their consent. “The community’s response? Outrage,” read a tweet from newly elected U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who will represent sections of the borough that abut Long Island City.

But what of Brooklyn?

Looking along 44th Drive in Long Island City, Queens, toward the towers of midtown Manhattan (Photo by Mark Lennihan/AP)

Like 238 other cities scattered across North America, Brooklyn put in its own bid last year for the headquarters project, known as HQ2. In an open letter to Amazon, Borough President Eric Adams advertised Brooklyn as though it were an independent municipality—“America’s fourth- (and soon-to-be third-) largest city”—while touting the area’s tech-centric universities, skilled workers, thriving neighborhoods and abundant mass transit.

Given the borough’s impassioned pitch, some Brooklynites may view Amazon’s choice of Long Island City as a snub. But with Amazon pouring an estimated $2.5 billion into a neighborhood just across Newtown Creek, the company’s arrival in Queens is sure to have an outsized impact on Kings County as well.

Potentially, here’s how:

The Prospect of New Jobs

The NYCEDC says that with Amazon’s second headquarters coming to Long Island City, the company “will draw from the diverse and talented workforce” in the area to fill a minimum of 25,000 new jobs by 2029. Up to 40,000 jobs are expected to be created by 2034.

“With an average salary of $150,000 per year for 25,000 new jobs Amazon is creating in Queens, economic opportunity and investment will flourish for the entire region,” Cuomo said in the NYCEDC’s press release. “Amazon understands that New York has everything the company needs to continue its growth.”

Regina Myer, president of Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, a collective of local leaders committed to the neighborhood’s prosperity, echoed that sentiment in an interview with The Bridge after the announcement. Though she’d hoped HQ2 would have landed in Brooklyn, Myer stressed that Amazon’s decision to build anywhere in the five boroughs is “a net positive” and “great news for all of us.”

“I really think that having this kind of job growth in the city of New York is exactly what we need,” she said. “Amazon made the decision to come to New York City … because they knew they could find talent, and to me that’s why this is such an important move for New York.”

Myer added that she’s certain there will be “some fantastic spinoff” in the form of “other tech companies moving to either New York City, or, obviously, my first choice would be Brooklyn.” She observed that members in the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership and officials in the area have been “spending so much time building on the strengths” of nearby tech schools like the NYU Tandon School of Engineering and City Tech, part of the Brooklyn Tech Triangle that includes innovative companies and startup incubators in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Dumbo.

Amazon workers in its campus in Seattle, where its employs more than 40,000 people (Amazon photo)

“We are excited about Amazon’s decision to co-locate its new headquarters in New York City,” said Jelena Kovačević, dean of NYU Tandon, in an email to The Bridge. “While the company’s needs in such areas as computer science, AI, cybersecurity and tech management will surely be a boon to the school and our students—providing internships and employment opportunities—it will also help accelerate the existing growth of the Brooklyn Innovation Coastline. … While NYU draws students from all over the U.S. and world, most stay on and work here in New York.”

But what about Brooklynites without engineering degrees? The potential ripple effects on other industries have yet to be charted, though Amazon says that in Seattle, 53,000 additional jobs were created as a result of the company’s investments there, besides its direct payroll. In New York City, the construction trade may be the first to benefit.

The building of the HQ2 complex is expected to create an average of 1,300 direct construction jobs annually through 2033, according to the NYCEDC. Gary LaBarbera, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, said in the press release: “We look forward to working closely with Amazon and the community to ensure that the project includes good middle-class construction jobs with benefits and high-quality permanent jobs.”

Amazon’s HQ2 is estimated to create more than 107,000 total direct and indirect jobs, as well as over $14 billion in new tax revenue for the state and a net of $13.5 billion in city tax revenue, according to the NYCEDC. The city and state expect an overall 9:1 return on their investment from the tax incentives being offered.

Big Development, Higher Costs

The arrival of Amazon’s campus is likely to supercharge the residential-development boom already underway in Long Island City, as well as the neighborhoods to the south in Greenpoint and Williamsburg. According to a report from Localize Labs, which analyzed data from the city’s Department of Buildings for the year beginning July 1, 2017, Long Island City saw 1,436 new housing units approved by the DOB, the most of any neighborhood in the five boroughs. Williamsburg ranked ninth on that list with 677.

Even more is in the pipeline. Long Island City also had the highest number of apartments with permits awaiting approval during that time, with 2,597. Greenpoint came in second, with applications filed for 1,493 units. So in terms of available space, if there’s any area in the city that’s geared up to house an influx of new Amazonian workers, it’s Southwest Queens and Northwest Brooklyn.

Just to the south of Long Island City, along a half-mile stretch of the East River waterfront, the Greenpoint Landing development is expected to include 5,500 residential units within a decade. Just to the south of that future skyline, plans are underway for a 40-story, mixed-use tower at 18 India St., just across the street from The Greenpoint, a just-completed residential tower of the same height. The 18 India St. building is expected to include about 470 new units, some of which will be deemed affordable housing. An 11-story building on the rise at 30 Kent Street will house 80 units, to name a few of the many new developments in the neighborhood.

Amazon’s complex in Seattle includes 33 buildings with more than 8 million sq. ft. of floor space (Photo by Jordan Stead/Amazon)

Plenty of new apartments, but at what prices? The demand from well-paid Amazon employees is likely to reignite the rise of rents and residential-property values in Brooklyn, at least in the vicinity of the new campus. Kara Dusenbury, director of sales at the Williamsburg-based Brick & Mortar real-estate firm, told The Bridge that asking prices at new condo developments in Greenpoint are “a little under $2,000 a square foot.” She called that figure “crazy.” “I remember along McCarren Park, in 2007, the asking price was $600,” Dusenbury said. “This is three times as much, what, in 11 years?”

Will Brooklyn become the next Seattle, overwhelmed by Amazon’s presence? “When Amazon first moved in, Seattle wasn’t even near the top of America’s priciest housing markets. Today, at a median home price of $739,600 and median rent of $2,479, it’s now the third-most expensive housing market in the country,” wrote real-estate reporter Aly J. Yale in a Forbes article. But New York City is a far bigger place, “one of few cities that can best absorb HQ2 with minimal disruptive impact.”

Transit Innovation and Expansion?

Much of the transportation burden will be borne by the 7 train, carrying east-west traffic between Queens and Manhattan. But Brooklynites commuting to Long Island City will depend in large part on the L and G trains, the former about to undergo a shutdown for tunnel repairs and the latter not well equipped for high-volume traffic.

“I think the L train shutdown will be a good test run of what transit will look like once HQ2 is finished,” John Surico, who covers transit for Vice, said in an email to The Bridge. Court Square will be “an even more crucial (and crammed) hub; local buses and ferries exacerbated with passengers; and more transfers onto other train lines. If the city and state were smart, they’d learn from whatever flaws arise in the L train shutdown, and make sure they’re fixed before HQ2 arrives.”

The G train is expected to get additional cars in the wake of the L train shutdown, and Surico expressed hope that they’ll remain on the line after the L is up and running again, easing the added congestion HQ2 is almost sure to bring.

A rendering of the proposed BQX streetcar passing Industry City in Sunset Park (Image courtesy of Friends of the BQX)

The arrival of HQ2 adds fuel to the argument for an expensive mass-transit proposal whose momentum had seemed to be flagging: the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, a streetcar line known as the BQX. Since its announcement in 2016, with the mayor’s blessing, the plan has endured numerous stops and starts due to questions about funding, how long it should stretch, and whether it’s even necessary. But the disclosure of the planned location of HQ2 right along the proposed streetcar track, stretching 11 miles from Astoria to Gowanus, immediately ignited speculation that a stronger rationale for the project could get it back on track.

“It’s undeniable that the BQX would provide a powerful benefit for Amazon and its future employees, but its benefits would be far broader, serving an emerging jobs corridor along the East River in LIC, the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Downtown Brooklyn,” said Jessica Schumer, executive director of the advocacy group Friends of the BQX, in a statement.

The BQX “will also connect underserved communities to employment, education and workforce development opportunities that will surely follow Amazon’s arrival,” Schumer continued. “Now is the moment to seize on this potential for equitable transit planning, to deliver the reliable option so many communities along the corridor have long lacked.”

The Daily News postulated that the revenue generated locally by Amazon could chip away at the $1 billion Mayor de Blasio recently said the city would need from the federal government to complete the BQX.

“We’ve been a huge proponent of the BQX,” the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership’s Myer told The Bridge. “The proximity to Greenpoint and Williamsburg is also part of the attraction of Long Island City [to Amazon], and in terms of the greater Brooklyn area, that just makes the commercial vitality of Williamsburg and Greenpoint all the more important, and for me there’s connectivity to Downtown Brooklyn through that.”

In a statement emailed to The Bridge, Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce CEO Hector Batista called Amazon’s tapping of Long Island City for half of its HQ2 “a win for Brooklyn,” and offered a similar pitch for the BQX: “I’m sure many Brooklynites will be commuting to Long Island City to work at Amazon. So, this is actually a great time to get to work on projects like the BQX light rail in order to help us continue to grow our local talent and economy along the thriving coast of Brooklyn and Queens.”

Why Weren’t We Consulted?

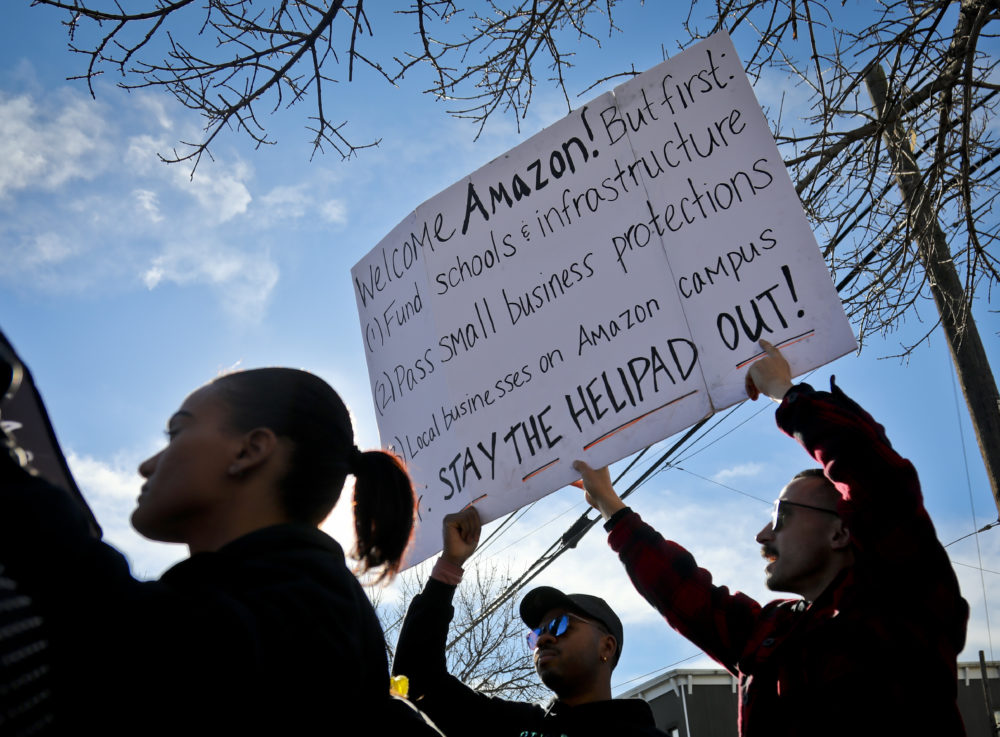

Despite the seeming windfall of billions of dollars in economic development, many local elected officials didn’t share Cuomo and de Blasio’s sense of triumph. Queens and Brooklyn politicians appeared to have two main objections: the handout of tax incentives that seemed excessive given Amazon’s trillion-dollar scale, and the lack of local input on the deal.

Many are angered over the fact that “according to the broad contours of the plan, the state and the city will bypass the City Council, which has the power to block rezoning and land-use measures,” wrote the New York Times as the deal was being finalized. “They will instead employ a state-level process previously used for large-scale development projects, such as Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn and Hudson Yards on the Far West Side of Manhattan. The price tag in city and state tax breaks [in the Amazon agreement] appeared to exceed those of other projects.”

Protesters hold up anti-Amazon signs during a coalition rally and press conference in Long Island City on Nov. 14 (Photo by Bebeto Matthews/AP)

In a joint statement, Michael Gianaris and Jimmy Van Bramer, who represent Long Island City in the State Senate and City Council, respectively, said that they have “serious reservations” about Amazon’s HQ2 coming to Long Island City. “Corporate responsibility should take precedence over corporate welfare,” they wrote. “If public reports about this deal prove true, we cannot support a giveaway of this magnitude, a process that circumvents community review … or the inevitable stress on the infrastructure of a community already stretched to its limits.”

Brooklyn Borough President Adams expressed his displeasure over the deal in a press release—and it had nothing to do with Brooklyn being passed over for the HQ2 site: “I was dismayed to hear that the City and the State have signed off on a plan that has shut out the level of robust community review that New Yorkers expect and deserve.”

He asserted that “a top-down approach to community planning is not sustainable over the long term,” and that he “will review the plan closely, with a keen eye on the commitment to sustainable local hiring and infrastructure investment both in Long Island City and surrounding communities—including neighboring north Brooklyn.”

In an email to The Bridge, City Council Member Rafael Espinal of Brooklyn, who chairs the Committee of Consumer Affairs and Business Licensing, called the agreement “tone deaf to what the city needs and is being conducted behind a veil of secrecy.” He also cited the “egregious labor practices” that Amazon is known for—including the suppression of unionizing efforts on the part of its workers, low wages and long hours, and poor warehouse conditions—as another source of his frustration.

“I strongly urge the city, state and Amazon to rethink the approach here so that the community has input and we can decide what is best for our neighborhoods,” Espinal said.

In New York, a way forward is more complicated: Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the deal as a General Project Plan (GPP), a special genre of development that doesn’t need to go through a state or city vote. So instead, some New York legislators are drafting new laws aimed at preventing as much bloodletting in the next bidding war. And others are trying to find a legal way to challenge the GPP retroactively.

Says Gianaris, the second-ranking Democrat in the State Senate: “We’re looking to delete what just happened and reset.”