Brooklyn’s Latest Small-batch Product: Electricity

How a Gowanus microgrid illuminates the future of power generation

Lawrence Orsini, founder and CEO of LO3 Energy, on a Brooklyn rooftop solar installation. (Photo credit: Sasha Santiago/LO3 Energy)

What if your local bodega sold not only potato chips, six packs and toilet paper, but 14 kilowatts of solar-generated electricity? That’s the future think behind Park Slope-based LO3 Energy’s innovative project, Brooklyn Microgrid, which pioneers the idea of electricity as a home-grown commodity.

Not far from the aromatic Gowanus canal, in a Brooklyn neighborhood blossoming with hotels, a boutique ice-cream shop and a barbecue hall, LO3 Energy is rolling out its test case in a five-block by five-block power grid, which by midyear will include 40 electric meters that monitor current in two directions: coming and going. If the test goes well, they will take up more participants on a rolling basis. The first test, in April 2016, connecting two neighbors on President Street, proved out the basic concept and technology. The buying neighbor paid his solar-generating neighbor around $13 a month in credits for his excess power. Distributed electric grids are a growth technology right now. The benefits are many:

- Decentralizing power distribution for better security in case of a terror attack or weather emergency;

- Reducing the energy loss from sending current over long stretches of wire;

- Exploiting innovations in solar and wind energy that allow homeowners to produce power beyond their needs;

- Meeting the demand of growing cities so utility companies don’t need to build more expensive power plants.

The Brooklyn Microgrid, which is organized as a public-benefit company, was launched primarily to address that first need: safety. When Superstorm Sandy blasted the east coast in 2012, the Gowanus Canal flooded, knocking out power to businesses and residents for more than three weeks. That caused job layoffs in some blocks, and the 3,000 people living in the Gowanus housing projects suffered a devastating 11-day loss of power. Initially, LO3, a power-technology startup, signed on to construct a parallel grid system using ConEd’s utility wires. That way, if the traditional grid were knocked out, the neighborhood could change over to locally generated energy, primarily a combined heat-and-power system in the housing projects using natural gas to generate electricity and diverting the remaining power for heat.

Solar panels atop houses in Gowanus provide electricity for neighbors when the owners have a surplus. (Photo credit: Sasha Santiago/LO3 Energy)

While embarking on that project, the LO3 team imagined other potentials for the microgrid, including locally sourced clean energy. When people buy into energy plans that seem to deliver wind- or solar-powered energy to their city homes through the large utilities, they are not literally receiving a direct stream of clean power but underwriting the construction of renewable generation upstate or even farther away. The concept is that all electron generation goes into the same pool, but the likelihood that a Brooklyn resident is getting an electron from a Syracuse renewable is slim, simply because the grid pulls from the closest source of energy. “People in the community who think they are getting green energy are really getting their electrons from a fossil-fuel based source. People don’t understand that,” says Scott Kessler, LO3’s director of operations. “One person even told us she was using more energy because she thought she was supporting the green initiative. We think there should be a direct local tie between what you are buying and what you are getting.”

Why a Microgrid in Gowanus?

The Gowanus area offers a particularly useful laboratory for energy solutions that LO3 hopes to apply around the world. Gowanus presents an intriguing socio-economic mix of residents; architectural diversity including small brownstones, large multifamily homes and industrial warehouses; and a strong environmental consciousness. Active early adopters include Whole Foods, which generates most of its own energy needs through a solar canopy, windmills and a combined heat-power unit. Kessler says Brooklyn has barely begun to tap its own potential riches. “New York has better solar potential than Germany,” he says, “and Germany has so much solar installed, at a certain point in the year, people were paid to consume it. It gets to a negative cost.”

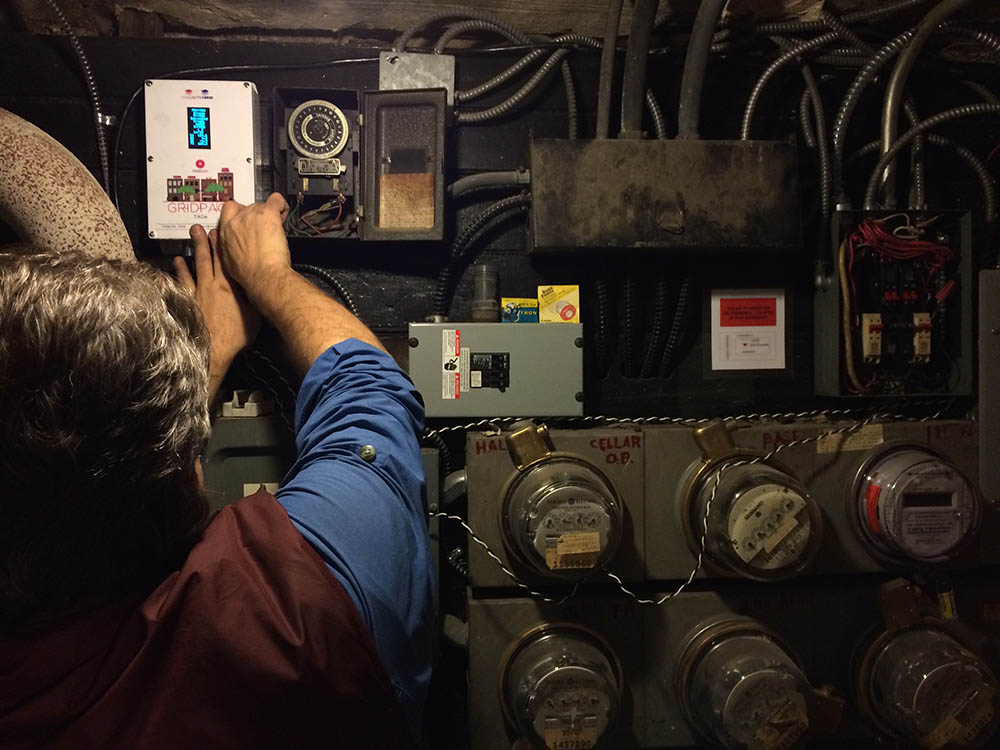

Joining the microgrid involves the installation of new meters that measure power traveling in two directions. (Photo credit: Sasha Santiago/ LO3 Energy)

So Brooklyn neighbors selling solar energy to one another should be a no brainer. But a few problems stand in the way. One, it’s illegal in New York State for people to privately sell energy; it must go through the utility. LO3 Energy answered that problem by designing an app called TransActive Grid, based on blockchain, the digital-ledger system that powers Bitcoin. The app allows grid participants to transform their energy into non-monetary units, set their top price for buying local power, and have it delivered whenever that price is right.

Let’s say a cloudy day reduces solar harvest and the demand outstrips normal supply. The price might rise. When it rises to a level that is beyond the consumer’s pre-set limits, the consumer would switch over to the standard carbon-based grid for consumption. If the microgrid creates an abundance of solar energy and the price is favorable, the consumer can have a home or business run entirely by neighborhood clean energy. The provider, meanwhile, would receive a credit from the utility company.

Scaling It Up

One might think that the big power utilities would resist the idea of home-grown power, but Kessler says they show real interest. “There are folks in the utilities business who are really into this. They think it’s the coolest thing in the world. They love solar and renewables. They just can’t figure out a way that it doesn’t put them out of business. And New York is trying to get ahead of that,” says Kessler. By state law, a large portion of a consumer’s electric bill is a fixed cost for maintenance of the overall system, protecting the utility from financial losses based on the ups and downs of energy consumption. One day, however, electric rates might be based on the distance from generation. So getting your power locally could theoretically lower your bill. That change is a long way off, but the dream is charging up along the Gowanus canal.