The Business of Brooklyn: an Amazing History in 20 Artifacts

Think we're inventive here now? A new show looks back in wonder at more than a century of progress

The Brillo cleaning-supply company got started in 1917 in Dumbo, founded by a jeweler and a cookware peddler. They packaged steel wool with soap cakes and later figured out a way to embed the soap in the pads (All photos courtesy of the Brooklyn Historical Society, except where noted)

Thomas Mellins, an architectural historian and independent curator, had a tough assignment. The goal: to tell the sweeping history of more than a century of business in Brooklyn through about 130 items. “The topic of business in Brooklyn is vast–in fact, it was a little intimidatingly broad–so I selected images and objects that encapsulated large themes, such as the processes of industrialization and de-industrialization; the simultaneous presence of big business and mom-and-pop shops; and the ‘Did-you-know-that-was-made-in Brooklyn?’ phenomenon,” he told The Bridge.

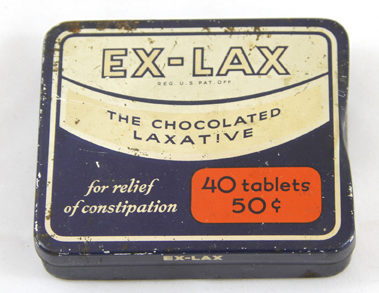

The result, The Business of Brooklyn exhibition at the Brooklyn Historical Society, is indeed full of surprises, probably even to longtime Brooklynites. Examples: One of the first modern oil refineries was in Greenpoint. North Brooklyn was a regional brewing capital. Two major pharmaceutical companies, Pfizer and Squibb, got their start here (not to mention Ex-lax). Brooklyn sold the world pencils (Eberhard Faber), bubble gum (Bazooka) and artificial sweetener (Sweet’N Low). Indeed, Brooklyn’s current reputation for inventiveness has deep roots.

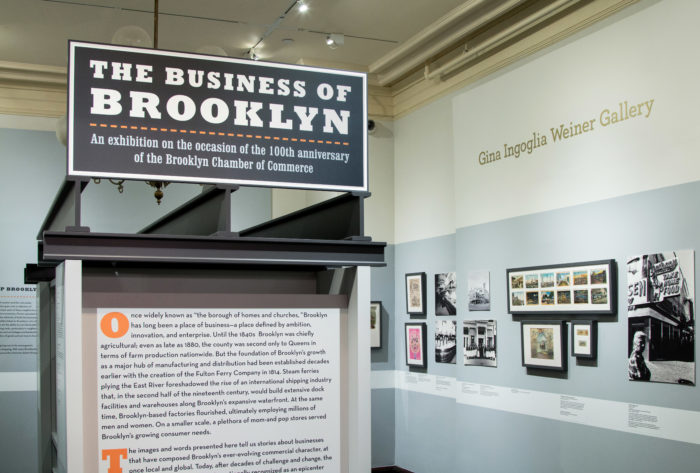

The show at the Brooklyn Historical Society will be on exhibit till year’s end (Photo by Denise Bosco)

The show, marking the 100th anniversary of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, is a celebration of business innovation, but it also tells the story of struggle. “I thought it was important to acknowledge the historic existence of barriers to success and struggles to achieve economic justice,” said Mellins.

The exhibit will be on display till the end of the year. We offer a compact version, with commentary from the curator:

1. Producing to a higher standard

Dr. Edward Robinson Squibb, a U.S. Navy doctor, “was so unimpressed by the quality of medicines available on ships that he threw the unfit drugs overboard,” according to the Squibb company history. He founded his pharmaceutical company, E.R. Squibb, M.D., in Brooklyn in 1858. The pioneering venture had higher standards for quality control than what was required by the American Medical Association. “It’s an example of industry actually pushing government rather than government regulating industry,” says Mellins. Squibb merged with Bristol-Myers in 1989 and now calls itself “a global biopharmaceutical company.”

2. A Brooklyn tale of two sweeteners

(Photo by Denise Bosco)

The American Sugar Refining Co., later known by the Domino Sugar brand, moved to Williamsburg in 1857 after having previously been based in Manhattan. By 1870, the company was responsible for refining more than half of the sugar consumed annually in the U.S. The main refinery, adorned with its iconic neon sign in the late 1960s, defined the North Brooklyn waterfront and is now being turn into a sprawling office-and-residential complex by Two Trees Management, the company that redeveloped much of Dumbo.

(Photo by Denise Bosco)

In the 1940s, Ben Eisenstadt, a maker of tea bags, was in a restaurant one day with his wife Betty Gelman, who ordered tea. Her tea arrived with the usual sugar bowl and spoon (and flies circling around), which prompted them to wonder, “Why doesn’t sugar come in an individual packet?” Eisenstadt told sugar companies about the concept but didn’t patent it, so he never fully capitalized on that idea. In 1957, however, he came up with a powdered saccharine mixture, put it in pink packets, and called it Sweet’N Low. The product was a hit and continued to be made in Fort Greene until 2016, when the company moved production to another facility.

3. Come to order, Brooklyn Chamber members!

The Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1918 and in less than a decade was the second-largest chamber in the U.S. Among other distinctions, in 1922 it led social change by allowing women to join. This gavel, from 1925, “was used in the Chamber’s meetings and is engraved with the names of the organization’s presidents, beginning in their founding year,” says Mellins. Today the Brooklyn Chamber has more than 2,000 members and was named the state’s chamber of the year in 2017.

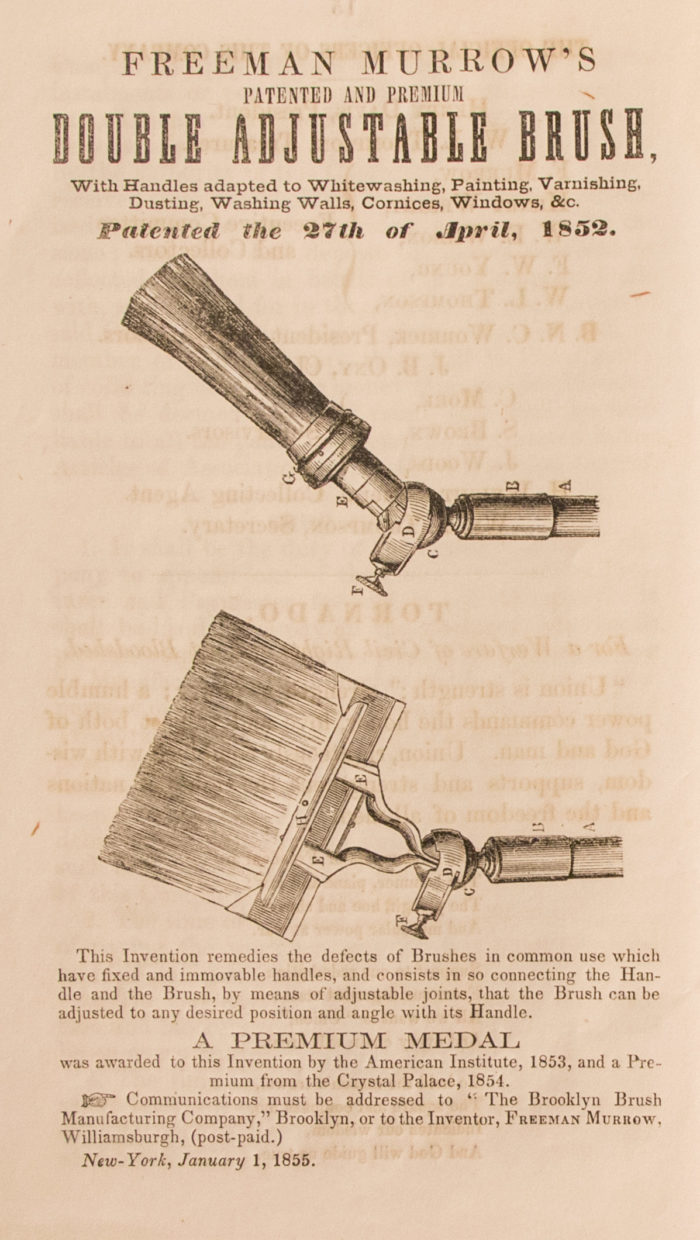

4. A black inventor's breakthrough patent

Freeman Murrow, an African-American inventor, patented a design in 1852 for an adjustable paint brush and established a company to produce it, the Brooklyn Brush Manufacturing Co. Because of his skin color, however, Murrow wasn’t allowed to display or demonstrate his own invention. He hired a white person to demonstrate the product in public at New York’s famed Crystal Palace exhibition, but stood by his proprietary rights in setting down the company’s bylaws. “What’s fascinating about these rules is that they directly refer to the U.S. Constitution. They are not mincing their words,” says Mellins. “They talk about being disenfranchised by the government and how important entrepreneurship is for the African-American community in New York.”

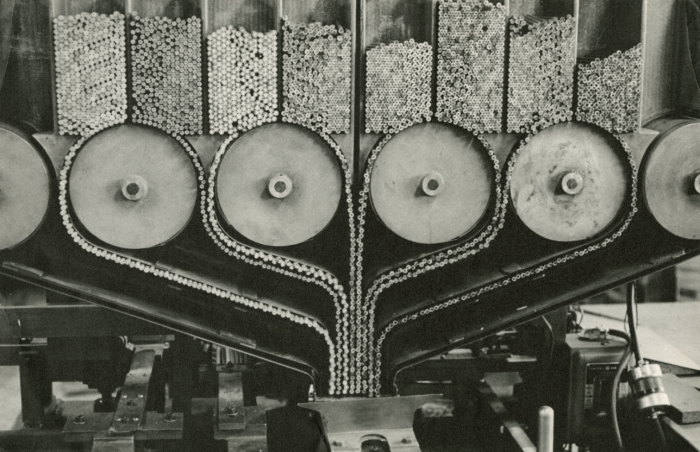

5. Brooklyn-made pencils had the write stuff

(Photo by Denise Bosco)

John Eberhard Faber, whose family had been making pencils in Bavaria for around a century, emigrated to the U.S. in the 1860s and started making pencils in Manhattan. After a factory fire, he moved his operations to Greenpoint, where he established one of America’s biggest pencil makers. The Mongol–a yellow pencil named for his favorite soup, purée Mongole–came to dominate the marketplace, along with its Jersey City rival Dixon Ticonderoga. Faber is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery and his Greenpoint factory now houses studios for illustrators and designers.

6. First a refinery, then an institute of higher education

In 1867, Charles Pratt built one of the first modern oil refineries in the U.S., the Astral Oil Works in Greenpoint, which produced kerosene for lighting purposes. In 1874, the company became part of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil trust. “It’s an example of a Brooklyn-based company becoming a part of one of the major industrial corporations of the world,” observes Mellins. “And then Pratt himself becomes very focused on the fact that these emerging industries in the U.S. are going to require a technical expertise that is not widely available in this country. So he established Pratt Institute because the industrialization of the U.S. is going to require a different level of education.” Today the institute, which has a 25-acre campus in Clinton Hill, is at the forefront of design and tech education.

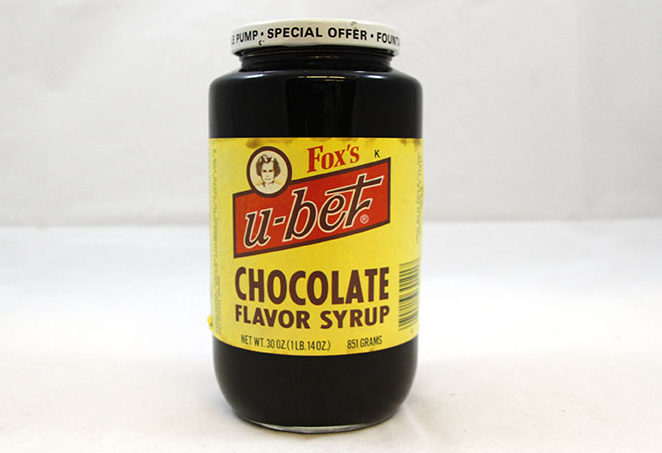

7. The syrup that made a New York beverage famous

In 1895, Brooklyn’s H. Fox & Co. started making its U-bet Chocolate Flavor Syrup, which would become an essential part of soda-counter culture. U-bet syrup was a key ingredient, along with seltzer water and milk, in the celebrated fountain beverage, the egg cream. (It famously contains neither eggs nor cream.) The syrup is made with real cocoa; the popular kosher-for-Passover version is made with cane sugar instead of corn syrup. Today the syrup comes in many other flavors as well, and is made by the same company that produces another Brooklyn creation: Gold’s prepared horseradish.

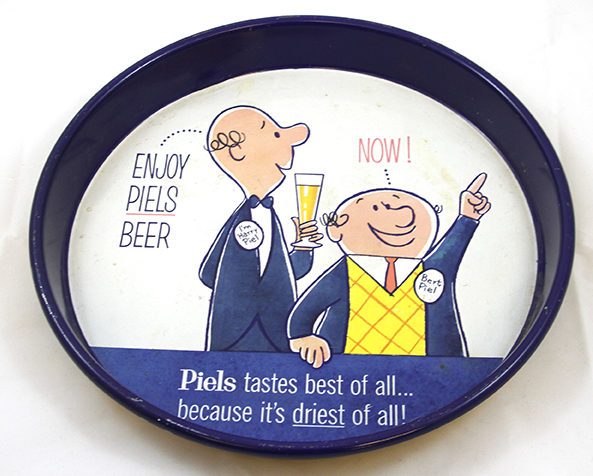

8. Bert and Harry Piel, ambassadors of Brooklyn beer

In 1883, the German brothers Gottfried, Willhem and Michael Piel bought a small existing brewery in East New York and began brewing traditional German lager with modern innovations. Along with other immigrant brewers, they soon helped established North Brooklyn as the brewing capital of New York. The Piels tray in the exhibit is from 1955, when the Brooklyn beer industry near its peak, and represents a novel collaboration between Brooklyn manufacturers and the “Mad Men” era of advertising.

“The fun thing about this tray is the two characters depicted on it,” says Mellins. “They’re fictitious characters. It’s Bert and Harry Piel. And the company uses them in print ads, radio, television and on merchandise. And they hire the comedians Bob and Ray to be the voices for their spots.” Like other regional beers, however, Piels was soon challenged in the marketplace by big national brands. By 1976, Brooklyn had no breweries left; a decade later, the comeback began.

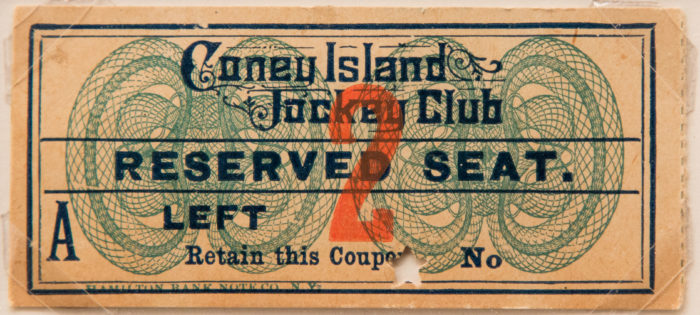

9. A horse-racing mecca that led to roller coasters

(Photo by Denise Bosco)

While Coney Island is most associated with carnival rides and freak shows, at one time it was a center for horse racing. The Coney Island Jockey Club, which opened in 1880, was among three tracks that drew the wealthy and sporty, establishing the area as a warm-weather playground. “At that time there’s an element of the rich, followed by the increasing democratization of entertainment and recreation in the city,” says Mellins. Anti-gambling sentiment led to the closing of the tracks in the early years of the 20th century, but today Coney Island is being refurbished with new rides, restaurants and other attractions.

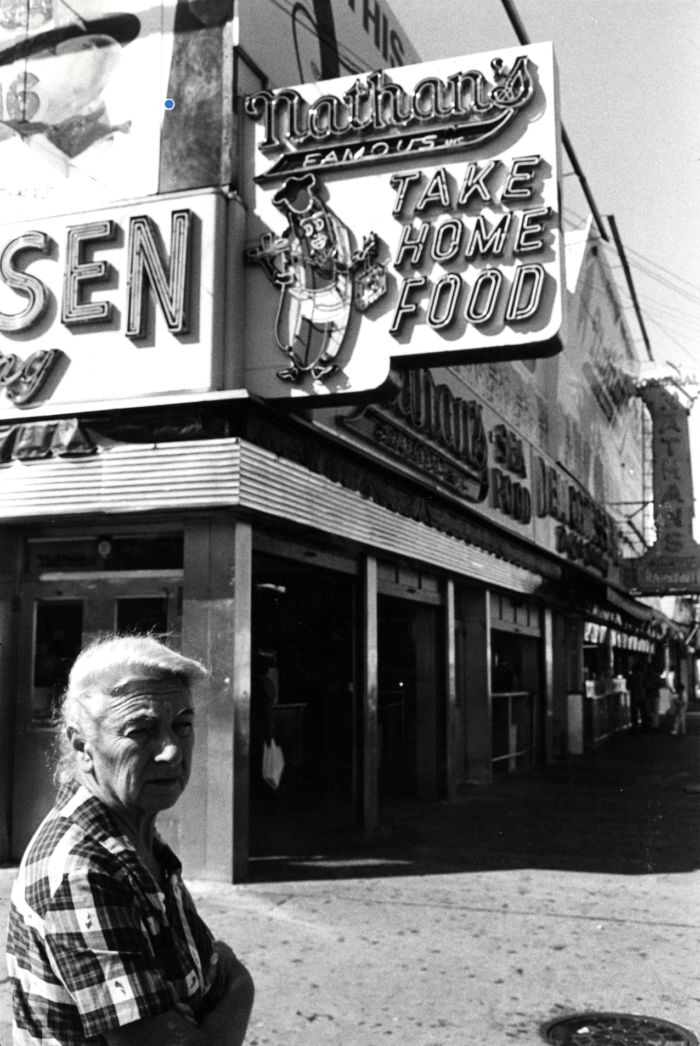

10. The frankfurter that became synonymous with Coney

(Photo by Anders Goldfarb, 1983)

Nathan Handwerker, a Polish immigrant, launched his claim to frankfurter fame with savings of just $300.“He opens up a hot-dog stand near the Coney Island boardwalk. He uses a recipe that comes from his wife, in the tradition of Polish sausages, things like kielbasa,” says Mellins. Handwerker did not invent the Coney Island hot dog–that distinction usually goes to entrepreneur Charles Feltman, who built a small boardwalk empire around his German beirgarten fare. But Handwerker priced his hot dogs lower, for the masses–and eventually mass consumption. Nathan’s was the fame that endured.

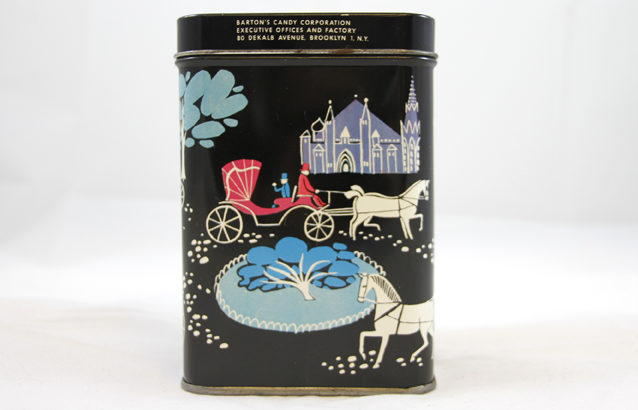

11. Bringing sophistication to candy–and its packaging

Barton’s Candy was founded by Austrian immigrant Stephen Klein, who came to America as a refugee in 1939. His family had been candy makers in Austria for generations and Klein brought those confectionary skills with him. “Americans knew about Hershey candy bars, but they didn’t understand the next level,” says Mellins. Barton’s also introduced Americans to ornate package designs. “In addition to bringing a sophisticated product, he also brings sophisticated product design. And the tin that’s on display has a kind of flair to it. This is not just selling the product, but selling modernity. The design has a crisp, Viennese look to it, with bright colors on black background–not the typical American design of that period.”

12. A shooting sportsman becomes a defense contractor

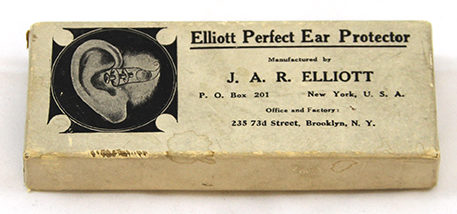

James Albert Riley Elliott, a champion trap shooter who worked for the Winchester company, got a tip that would turn quite profitable. He was friends with John Philip Sousa, the bandleader and avid trap-shooter, who complained that the exposure to all the gunfire was affecting his hearing. (Shooters at the time wore no ear protection.) That inspired Elliott in 1911 to invent and patent the Elliott Perfect Ear Protector, which became a successful product that he sold mostly to gun clubs, but also to the military. “You know, military contracts are a big source of wealth in this country and part of its business history. And this is a very specific example of that,” says Mellins. Wealthy indeed, Elliott lived in a giant stone mansion in Bay Ridge. Today one of Brooklyn’s most prominent defense contractors is Crye Precision, which makes state-of-the-art body armor.

13. On Atlantic Avenue, a Middle Eastern market since the 1940s

(Photo by Jim Kalett, circa 1983)

Sahadi’s, the iconic Middle Eastern grocery store, was founded in lower Manhattan in 1898, but its Brooklyn chapter began in the 1940s, when the Lebanese-American family joined many fellow residents of the Little Syria neighborhood who were uprooted by the construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Many of them moved across the river to the Atlantic Avenue area of Brooklyn, which became a corridor of Middle Eastern businesses that endures today. The thriving Sahadi’s recently announced plans to build a second, bigger store in Sunset Park.

14. The colorful originality of mom-and-pop storefronts

(Photo by James and Karla Murray)

Before the arrival of national retail stores, with their standardized look, Brooklyn was a colorful mosaic of expressive storefronts. These beacons of neighborhood spirit were anything but anonymous. Thankfully, many endure, including Gottlieb’s Restaurant, a kosher deli in Williamsburg founded by Hungarian immigrant Zoltan Gottlieb in 1962. Thankfully too, New York City’s storefronts have been photographed and collected into several books by James and Karla Murray.

“Mom-and-pop business was so key to Brooklyn’s identity–and to some extent still is,” says Mellins. “There are these little entrepreneurial ventures, and it’s very much about New York–and the U.S. by extension–as a place of opportunity.”

15. First a laxative factory, then a model of urban re-use

Ex-lax, the laxative brand, was produced in Brooklyn starting in 1906 by the Hungarian-American pharmacist Max Kiss, who named it as an abbreviation for “excellent laxative.” But its enduring legacy in the borough may have more to do with urban redevelopment, says Mellins. Pedestrians strolling along Atlantic Avenue in Boerum Hill can still see the brand name Ex Lax Inc. on the company’s former headquarters, which around 1980 was turned into condo lofts. “At the time that it was converted to a residential building, adaptive reuse was still a relatively new vehicle in New York. And it had to do with New Yorkers really understanding for the first time that there was a value in their existing buildings, and that you didn’t always want to tear things down.” Today Ex-lax is made by the pharma giant GlaxoSmithKline.

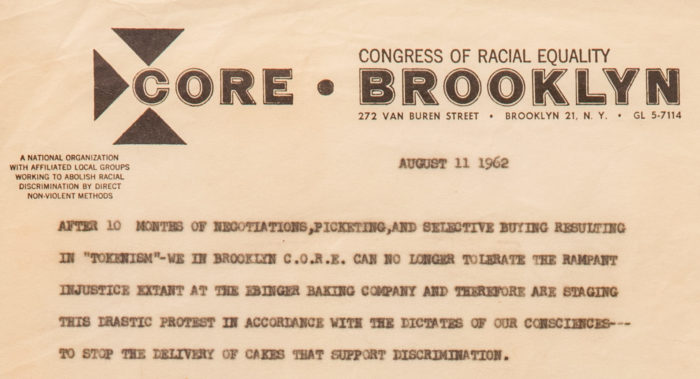

16. A bakery gets schooled about discrimination

(Photo by Denise Bosco)

Ebinger’s Bakery was beloved in Brooklyn. It opened its doors on Flatbush Avenue in 1898 and was famous for its “Brooklyn Blackout cake,” a chocolate cake filled with chocolate pudding and chocolate cake crumbs, topped with chocolate frosting. Less well-known was the bakery’s policy of refusing to hire people of color in the positions of salespeople, bakers or store managers.

In 1962, the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized demonstrations and boycotts “to stop the delivery of cakes that support discrimination.” These protests worked, and the bakery abandoned its biased hiring policy, though a requirement that employees had to live near the stores and factories where they worked helped to keep numbers of nonwhite workers low. The episode was an important reflection of changing demographics in the borough and also, says Mellins, it showed “a certain level of conflict and struggle. The story of business in Brooklyn has not been simply one success story after another, but efforts at unionization and fair hiring practices and decent workers’ rights.”

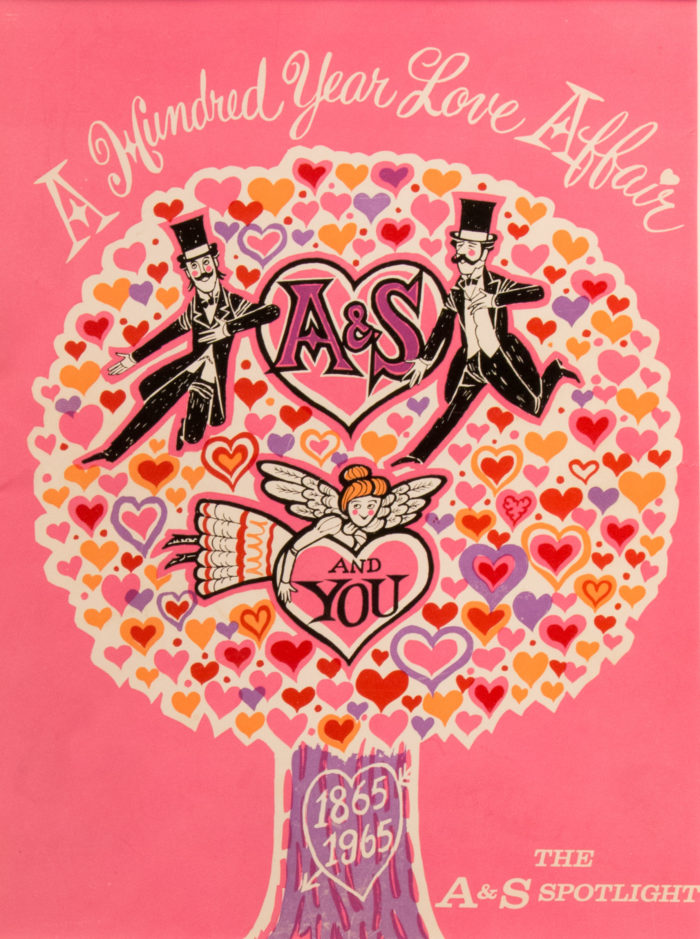

17. The department store that drew 70,000 shoppers a day

(Photo of poster by Denise Bosco)

“Department stores used to play a really important role in the New York economy and Brooklyn was no exception, where they weren’t simply places to buy things, but places to meet people and socialize,” says Mellins. “There were restaurants, lavish interior decoration, and enormous sales forces to help you.” In Brooklyn, that hub of cultural life was Abraham & Straus. “It was before there were malls and at a time when women were making a transition from very private, domestically focused lives to ones lived much more in public.”

The grand Brooklyn emporium had started small, a 25-foot-wide storefront opened in 1865 by a 22-year-old Bavarian immigrant named Abraham Abraham and his friend Joseph Wechsler. In 1893, the Straus family bought Weschler’s interest in the company and was renamed Abraham & Straus. The store grew and thrived; in the 1940s, it had an estimated 70,000 customers a day. By a half-century later, the brand name adorned 18 stores across the New York area. In 1995, however, the parent company converted them all to better-known national brands like Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s. The original Fulton Street flagship of A&S is now a Macy’s, which is being crowned with an office tower and will be part of a mixed-use complex called The Wheeler.

18. A pioneering campaign to bring a neighborhood back

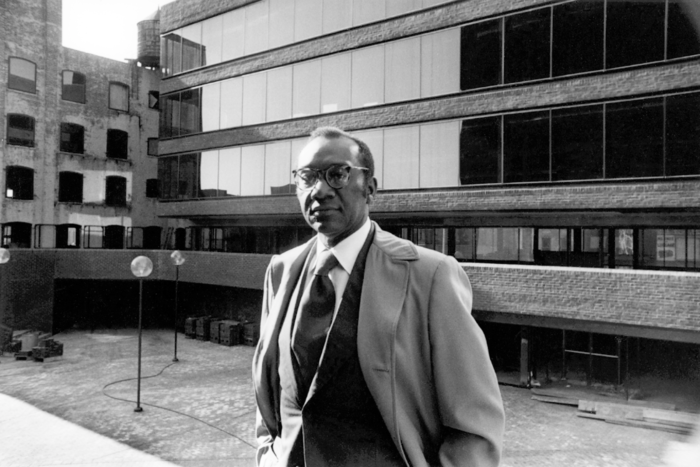

(Photo courtesy of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corp.)

In the mid 1960s, when the decline and neglect of Bedford-Stuyvesant had drawn national attention, New York Senator Robert Kennedy realized that something had to be done about it–and something bold. “People like myself can’t go around making nice speeches all the time. We can’t just keep raising expectations. We have to do some damn hard work, too,” Kennedy said.

He wasn’t wrong about the effort it would take. But a partnership of community leaders, elected officials and corporate executives set in motion the creation of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corp., which launched in 1967 as the nation’s first community-development corporation. Franklin Thomas, a deputy police commissioner, was chosen to be its first president. Above, he stood before a former milk-bottling plant that was restored to become the group’s headquarters, called Restoration Plaza. Since its creation, the group has built or rehabilitated 2,200 housing units and brought more than $500 million in investments to Central Brooklyn.

19. The first in a revived Brooklyn brewing industry

Brooklyn, which had 45 breweries at the beginning of the 20th century, had seen them all close by 1976 as national brands took over the industry. But a dozen years later, a remarkable comeback began. Former Associated Press foreign correspondent Steve Hindy and his former downstairs neighbor, Tom Potter, launched Brooklyn Brewery. They recruited the renowned graphic designer Milton Glaser to create the company’s logo, now a Brooklyn icon.

The brewery started with just one product, its signature Brooklyn Lager, but now offers an extensive list of hand-crafted beers that are sold all over the world with a growing number of business partners. And what the partners launched at the dawn of the craft-beer revolution has blossomed into a full-scale industry in Brooklyn, now including 20 brewing companies.

20. Brooklyn products that land on Mars

(Photo courtesy of Honeybee Robotics)

The Brooklyn Navy Yard, which went from building battleships to near-abandonment, has made an epic comeback as a hub for tech innovation and manufacturing. One of its most sophisticated residents is Honeybee Robotics, which makes devices for challenging environments–like Mars. Among its 300 projects since 1983 for NASA and the Defense Department, Honeybee developed two tool systems for Mars rover Curiosity to help gather samples of the planet’s surface. Above, Honeybee co-founder and chairman Stephen Gorevan stands with an engineering model of Curiosity; the rover has been exploring Mars since it landed in 2012.

Honeybee is just one of hundreds of technology ventures now calling the borough home. “Brooklyn is really keeping pace with the digital revolution,” says Mellins, “and now there’s a second cycle of Brooklyn becoming a desirable location for businesses.” And a window to the future. Among Honeybee’s works in progress: technology to sample and mine asteroids.