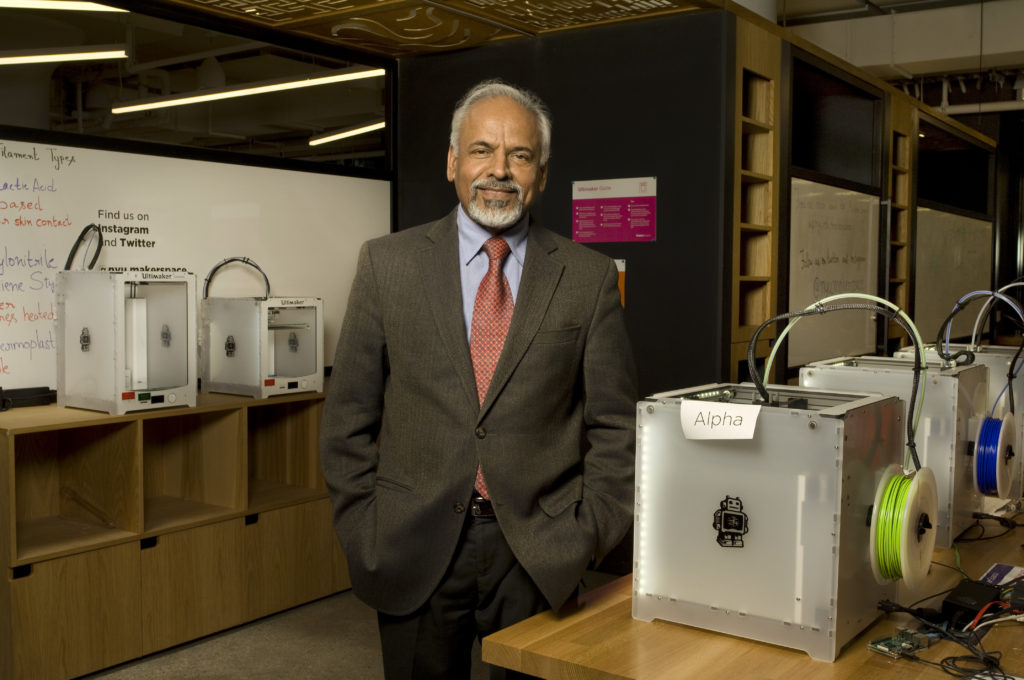

It may have been useful in his job for the past half decade that Prof. Katepalli Sreenivasan’s academic specialty is the study of turbulence. For the physicist’s task was to preside over the bumpy merger of two schools–one rich and one relatively poor, one in Manhattan and one in Brooklyn–who at times had shown animosity toward each other.

But as he steps down this week as dean of the now-combined institution, the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, Sreenivasan leaves behind a smooth-running engine of innovation. “Life has become very normal now, normal in the sense of how it is in well-established universities,” he told The Bridge, talking with satisfaction at having empowered the school’s departments to make many of their own decisions, decentralizing his own office’s power.

While preparing to hand over the job to his successor, Jelena Kovačević of Carnegie Mellon University, who’ll become the school’s first female dean, Sreenivasan talked with The Bridge about his legacy: how he helped make the merger happen, the school’s success in pursuing gender parity, its growing campus and rising reputation, and his planned next chapter–at age 70–diving deeper into aeronautics research.

A Reluctant Merger, at First

A year before Sreenivasan joined NYU in 2009, the school had created a formal affiliation with Brooklyn’s Polytechnic University, founded in 1854, as a step toward a prospective merger. Polytech had an illustrious past but was struggling with multimillion-dollar deficits, while NYU had lacked an engineering school since 1973.

A nice fit, in theory. But there was skepticism about the merger on both sides. Sreenivasan spent a considerable amount of time, he said, trying to educate NYU’s president and provost “about the virtue of having an engineering school in the university. They already made the agreement before I came, but I don’t think they had a clear idea of what they wanted to do with the engineering school.”

Sreenivasan, who as a half-time administrator sat in on meetings with NYU’s leadership, didn’t like what he was hearing. “I saw that [the merger] was not moving forward and everybody was really belittling Poly continually,” he said.

“And I said, ‘This is ridiculous.’ So I went to our president and said, ‘I’ll go to Poly for one day a week for a few weeks and then I’ll write up a little report, which is how it started. I thought they would forget about my report. But they didn’t, and ultimately I got stuck with the job,” said Sreenivasan with a smile, betraying that he feels quite the opposite about his role.

Tandon’s MAGNET (the Media and Games Network) center is a shared space for faculty and students who are pursuing projects at the intersection of culture and technology (Photo courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau)

“If I might tell you something that I haven’t told many people,” said Sreenivasan, “it was Polytechnic that kept me in NYU. It gave me a purpose. And the purpose was to make sure the school becomes integrated with the university and then it works well. Otherwise I had no purpose in NYU, if I didn’t do something that mattered.”

In 2012, the trustees of both schools voted to go ahead with the merger and Sreenivasan rose the following year from acting president of the Brooklyn school to its dean.

‘Let Me Try the Other Route’

While the deal picked up momentum, Sreenivasan campaigned to bring the parts together. “It was important for Tandon to connect with as many schools [within NYU] as possible. Unless you integrate like this, I was a bit worried that the merger might not really be successful,” he said.

On the Brooklyn side, there was lingering faculty resentment from earlier merger talks, in which NYU had shown a heavy hand. “There was the animosity towards NYU, which if [it] persisted, we just wouldn’t succeed. You cannot be a part of an institution and dislike it intensely.” The dean, who goes by the nickname “Sreeni” on campus, did his best to massage egos and reassure people who felt their territories were being invaded, he said.

NYU Tandon faculty in the school’s new cleanroom, designed for nearly contaminant-free research, with Borough President Eric Adams, far right (Photo by Arden Phillips)

The dean, however, had his own issue with NYU over its prescribed strategy for raising the academic quality of the Brooklyn students: by downsizing. “Every single one of the people in NYU told me you couldn’t get enough students who are also very good,” he said.

“The recipe they gave me was: Cut down the number of students so you can get very high quality. And then you will have to shrink the school by about 30% to 40%,” he said. “And that was going to be a recipe for disaster. You have to fire people, close departments. So I said, ‘Well, let me try the other route.'”

The other path, toward growth instead, proved successful. NYU Tandon’s enrollment last fall was 5,300 students, about evenly divided between undergraduate and graduate students, up from 3,300 a decade earlier.

The quality, judging by SAT scores of incoming students, has gone up steadily too, rising more than 200 points in recent years to an expected 1430 (out of 1600) for the class coming in this year. The school has moved up in its competitive set as well. While it used to compete for students primarily with local schools including CUNY and SUNY campuses, its top rivals now include the University of California-Berkeley and Carnegie Mellon.

A Major Financial Infusion

While the merger was complete by 2014, the school’s renaming happened the following year, after a $100 million gift from NYU trustee Chandrika Tandon and her husband Ranjan, both of whom had launched financial firms.

How did that come about? Chandrika Tandon was an acquaintance of the dean. “When I took charge of this place I got her to come to our board meetings, where I was saying what our vision is. And she got excited about it at some point and said, ‘OK, I can maybe give you some money, $30 million dollars.'” Sreenivasan referred the potential donor to the university’s president to cement the deal–and more. “Between them, they raised the money to $100 million. So that’s how it happened,” said the dean.

The impact of the gift, which was earmarked for faculty hiring and academic programs, was symbolic as well as financial. “The rest of the university started taking us even more seriously than they had before,” said the dean, who followed up by developing a strategic plan and asking the university for more financial support to carry it out.

A rendering of 370 Jay St., the former MTA headquarters that will almost double the size of NYU Tandon (Illustration courtesy of Mitchell I Giurgola Architects, LLP, and NYU)

The result, announced in January 2017, was a $500 million, ten-year plan to expand the Brooklyn campus. The showpiece is the refurbished former MTA building at 370 Jay St., which at 500,000 sq. ft. almost doubles the size of NYU’s Brooklyn footprint.

The Brooklyn school will share the building with other NYU departments once housed in Manhattan, including the Center for Urban Science and Progress, furthering Sreenivasan’s goal of weaving the two institutions together.

“There will be several other schools working together in a collaborative way,” he said, mentioning music, arts and gaming departments. “All the people who have interest in technology at large–they will all be there together. I think that’s a great thing. We will be an anchor in terms of technology, an anchor for the borough of Brooklyn in its technology growth.”

Furthering Women in Tech

NYT Tandon has reached an important milestone this year: virtual gender parity in its incoming freshman class. “Among the people who have deposited their initial money, 49% are women,” Sreenivasan said.

At a time when then gender gap in technology has become a pressing issue–the typical level of female enrollment in engineering schools is just 20%–NYU Tandon has made “a very conscious effort” to do better, the dean said.

Members of the Alpha Omega Epsilon sorority at NYU Tandon at a club-day event (Photo courtesy of AΩE via Instagram)

Among the tactics were energetic recruitment, generous scholarships, accommodations including optional women-only floors in the dorms, and “a group of women administrators whose goal is really to empower women in the school.”

When Sreenivasan studied the SAT scores of incoming men and women, he found an interesting pattern. “The scores were slightly smaller for women, but their success rate was higher. More of them are graduating than men are,” he said. “So in fact the slight difference there doesn’t count at all. I think women are more motivated somehow. They’re really excited to be part of a technology school.”

The school has focused increasingly on economic diversity as well. As a private school, “we are ridiculously expensive, I’m sorry to say. And to me it looks like we are missing out on an enormous number of very talented people,” the dean said. One new program specifically designed to be more inclusive is the school’s online masters degree in cyber-security, the New York Cyber Fellows program, with an effective tuition of around $15,000.

The response to the program, which will start in the fall, has been encouraging. “We had expected to recruit a hundred people. Now [Prof.] Nasir Memon, who runs this, tells me we will end up with many more.”

Research and Entrepreneurship

During Sreenivasan’s time at the helm, NYU’s research expenditures have more than doubled, to nearly $49 million in fiscal 2017, up from $21.4 million in 2014, funded by government, foundations and industry.

To conduct the growing research, the school has recruited 45 new faculty members during the dean’s time in office and added several new research centers in fields including wireless technology, virtual reality, transportation, and materials.

The school has just launched a biomedical engineering department, which does research on tissue engineering and 4D imaging. The emerging 4D technology could be applied, for example, to longitudinal surveys of the brains of children who have autistic problems, the dean said.

What’s distinctive about NYU Tandon’s research is that much of it takes place in entrepreneurial settings, including the school’s fleet of four Future Labs, including its new Veterans Future Lab. “They are not research labs per se, but they are really looking towards making money and being a part of the entrepreneurial community in New York City. That was another thing that I cared a lot about,” says the dean.

The startup environment was beginning to blossom at the beginning of the dean’s term, he recalled. “And so we sort of fell in line with it. It’s not like it was a grand plan, but I saw that it was really taking off in New York City, especially in Brooklyn. And so we became a part of it.”

A Scientist at Heart

Sreenivasan’s road to erudition began in his native India, in what he describes as “a very rural area, a small village,” in the southern part of the country. He grew up in “an ordinary, typical Hindu family,” according to a book, KRS 70, written by family, friends and colleagues to celebrate his 70th birthday.

The book, rendered in both English and Sreenivasan’s native Kannada language, describes a young man defined by a quest for equal opportunity. His own education “often meant sacrifices; as a young boy he had to walk long distances to school and moved away from home at an early age to continue his schooling,” wrote Sreenivasan’s son Kartik, an assistant professor at NYU Abu Dhabi.

Sreenivasan as a youth in India with his sisters (Photo courtesy of Katepalli Sreenivasan)

Sreenivasan pursued his education in India through the PhD level, then voyaged to the U.S., landing at Johns Hopkins and then Yale, where he became full professor within just a few years and stayed more than two decades. “I thought I would never move. Nobody who knew me thought I would move,” he said.

But other adventures beckoned, notably as director (in 2003-09) of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy, which provides fellowships for scientists from developing countries. “I went there because I really cared about developing countries, myself having come from one of them.”

It was in Trieste that he resolved never to get too far from hands-on research. “One of the things I promised myself was I will not be drowned out by administration. I will have to do some science myself,” he said, in order to serve as an example to his colleagues.

For the past couple of years, Sreenivasan has been itching to get back to research in his fields of turbulence and fluid mechanics, and has been talking with NYU’s leadership about concluding his tenure as dean, he said. This year the time was finally right. Starting in September, he’ll be on leave from NYU, working at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, where the likes of Einstein and Oppenheimer have studied.

The essence of his study, he explained, are non-linear problems. “If you give a small input to a system, if it is a linear system, the output would also be only a small difference. If you have a nonlinear system, small changes can produce very huge effects,” he said. The systems he studies, he said, range “from astrophysical to very microscopic.”

After his time as Princeton, he’ll return to teaching at NYU, where he has several appointments in the university. He particularly wants to focus on the department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

“Students are really excited about aerospace, as you can imagine,” but the school currently has few resources in that field, so Sreenivasan wants to create a new undergraduate lab for those students. He already has a Center for Space Science at NYU’s campus in Abu Dhabi, a place that is “very gung-ho on space,” the dean observed.

A Worthy Successor

While Sreenivasan had no voice in hiring his successor, he applauds the choice of Jelena Kovačević of Carnegie Mellon. “She is a terrific person. The right personality for the school. And I think she cares for some of the same things I cared about,” he said.

Jelena Kovačević, who will take charge of NYU Tandon this wek (Photo courtesy of NYU)

“She seems to value building things in substance rather than hyping them, which to me was extremely important. She also has seen the school from the time it was in bad days to now. She has actually seen the improvements that happened,” he said, “and she is very much in the mode of continuing all these things.”

At an an academic conference celebrating his 70th birthday, the outgoing dean listed three principles he had come to embrace during his career, including one about mentoring young people. “I resolved that if anyone wishes to talk to me about their careers or personal lives, I would give them the most honest advice I can and support them in the best way posssible,” he said.

“The lower in hierarchy they are, the more attention they deserve,” he continued. “My criterion has never been the perceived importance of the person in question, but his or her needs. Even if the problem vexing the person may be generic, it is special to her or him–and I have tried to remember that as well as I can.”