Who Are the Real Culprits Behind Hyper Gentrification?

In February 2014, with the slogan “Defend Brooklyn” on the sleeve of his sweatshirt, filmmaker Spike Lee gave a Black History Month talk to an audience of art students at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. During the Q&A, one student asked if gentrification had its good sides. “I don’t believe that,” Lee replied, launching into a defense of his home neighborhood, Fort Greene, where, along with the surrounding neighborhoods, the white population had increased by 120%, while the black population decreased by 30% in the decade between 2000 and 2010. The rents, of course, went up.

Lee recalled his childhood, when the garbage wasn’t collected and police weren’t out protecting the streets. Addressing the question about gentrification’s good sides, he asked, “Why does it take an influx of white New Yorkers in the South Bronx, in Harlem, in Bed-Stuy, in Crown Heights for the facilities to get better?” He railed against what he called “the motherfuckin’ Christopher Columbus Syndrome,” the urban phenomenon in which newcomers, usually middle-class and affluent whites, believe they’ve “discovered” a neighborhood, as if nothing and no one had been there before them.

Since at least the 1980s, the enduring metaphor of gentrification has been colonialism. The frontier. Ed Koch might have started it when he called for the “new pioneers” to “come east,” reversing the “go west” of Manifest Destiny, that 19th-century idea in which settlers were destined, preordained by God, to expand ever outward into untamed territories, spreading Anglo-Christian culture and values, while ridding those territories of their people.

Crown Heights residents and housing advocates protesting a plan for the redevelopment of the Bedford-Union Armory that included luxury condos (Photo by Pacific Press/Alamy)

Journalist John O’Sullivan first defined Manifest Destiny in 1845 as the right to “overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” This providentialism remains in America’s blood, linked back to Calvinism, to the Puritan colonists whose work ethic, with its belief in the preordination of wealth from God, formed the basis of American capitalism. We can feel it working today behind the revanchist takeback of the city.

The Frontier Myth in the City

Neil Smith, professor of anthropology and geography at the Graduate Center of CUNY until his death in 2012, outlined what is probably the most detailed and useful theory of gentrification and its changing shape. Writing on the frontier myth and gentrification, Smith explained how this mythologizing serves to cover up brutal realities. “As a new frontier,” he wrote, “the city bursts with optimism. Hostile landscapes are regenerated, cleansed, reinfused with middle-class sensibility” and “real-estate values soar.” Those who buy into the frontier myth tend to ignore or deny the human devastation that comes with it. When the poor and working class are repositioned, wrote Smith, “on the wrong side of a heroic dividing line, as savages and communists, the frontier ideology justifies monstrous incivility in the heart of the city.”

It is easy to cast the gentrifier of today as a one-dimensional villain. But what is a gentrifier? Are all gentrifiers monstrously uncivil, revanchist colonists? In the original definition, a gentrifier is a person from an upper-class group who moves to the neighborhood of a lower-class group. From there, it gets more complicated, but one thing is clear: Gentrifiers always have more social power than the people whose spaces they infiltrate. It may be the power of race, typically whiteness. It may be the power of class, which can sometimes be less visible. Seldom mentioned but important to note is the fact that many middle-class and affluent people of color are gentrifiers too, often in lower-income neighborhoods of color.

When talking about gentrification, we must keep intersectionality in mind. Sometimes all you need to be a gentrifier is the power of cultural capital. Penniless grad students from working-class backgrounds, actors and dancers working as waiters, black and Puerto Rican hipsters, and stylish queers all have cultural capital. And wherever City Hall and Big Real Estate look to commodify a new frontier, cultural capital is rapidly converted into economic capital. Which brings us to artists and gays.

Who Are the ‘Shock Troops’?

Artists are often branded as front-line gentrifiers. Sometime in the mid-1990s, people started saying: “Artists are the shock troops of gentrification.” The quote has been repeated about a hundred thousand times. Smith seems to have started it in his 1996 book, The New Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. “In the gentrification of the Lower East Side,” he wrote, “art galleries, dance clubs, and studios have been the shock troops of neighborhood reinvestment.” Not artists exactly. While they certainly play a role in the gentrification process—some more deliberately than others—it is inaccurate to equate artists with a powerful military operation. Worse, it distracts us from the real culprits.

The author’s new book, based on his blog chronicling the city’s transformation

In Rebel Cities, CUNY professor and urbanist David Harvey points out how the people “who create an interesting and stimulating everyday neighborhood life lose it to the predatory practices of the real estate entrepreneurs, the financiers and upper class consumers bereft of any urban social imagination.” The more interesting the neighborhood, “the more likely it is to be raided and appropriated.” Artists are often unwitting tools of the hyper-gentrification machine. As Author Rebecca Solnit noted, it’s not the artists’ fault that yuppies and developers follow: “After all, creeps tend to follow teenage girls around, but teenage girls neither create nor encourage them.”

Except, of course, when artists do encourage them. There are many examples today of artists putting their work on “art walls” and in other installations co-branded with developers and corporations working to tame and commercialize contested zones. In the East Village, for one, the controversial Icon Realty in 2016 hired street artists to paint murals on the sides of buildings they took over, including the one from which they evicted the beloved Stage Restaurant. It was an obvious attempt to sway negative public opinion. In their press release about the mural by Jerkface, they hit all the key words, describing him as a local, native artist known for his “nostalgia-inducing murals.” We might want Jerkface to decline the commission, but how does a working artist turn down a paycheck in a city that has become unaffordable to artists? It’s another vicious cycle.

A new movement of artists fighting gentrification is growing. At a 2016 public discussion called “Artists: NYC Is Not for Sale,” artists and activists, mostly people of color, gathered to talk about their own role in gentrification—and how to break the cycle. South Bronx native Shellyne Rodriguez asked, “What can we do to shake the developer fleas off our asses?” The answer was simple: just say no. Under the social media tag #nycnot4sale, the group distributed a kind of manifesto, a brochure with a pledge to refuse collusion with real-estate speculators. It read: “To the developers, we are weapons of mass displacement. By loudly refusing this role, we can become weapons of creative resistance.”

Gay men and women have also been scapegoated as urban shock troops. As early as 1983, gay men were linked with gentrification when sociologist Manuel Castells in The City and the Grassroots made the connection between gay social clustering in San Francisco’s Castro district with neighborhood upscaling. But the situation was not simple. While many middle-class gay men, Castells explained, were renovating buildings, other, less well-off gay men lived in “organized collective households” and “were willing to make enormous economic sacrifices to be able to live autonomously and safely as gays.”

Less attention has been paid to the ways that lesbians create social space, and they’ve been less often implicated in gentrification. Due to economic inequalities, women, and queer women in particular, may have less control over the environment than men, but they still cluster. In the 1980s and ’90s, Brooklyn’s Park Slope was so full of lesbians it was affectionately known as “Dyke Slope.” By 2001 they were being pushed out. Said Cynthia Kern, producer at the time of DYKE TV, to Brooklyn Paper: “I moved to Dyke Slope when it was strong. Then it became Puppy Slope. Now it’s Baby Slope. We can’t fit between all the strollers there.”

Today, queer young people—many of them artists—are living in intentional, often racially mixed, housing collectives across gentrifying Brooklyn. In the past, they might have had a decade or more before hyper-gentrification found them, exploited their cultural capital, and pushed them out—along with their neighbors. Today it happens overnight.

For my own young artist friends, the East Village is now irrelevant. They’ve never even visited. They make their art and live their lives exclusively in Brooklyn. This looks like good fortune—finally, a real bohemian enclave in corporatized New York!—but locomotive hyper-gentrification is revving at their door. The kids are barely hanging on, already priced out as they price out those with less money and less cultural capital, attracting speculators and stroller pushers who push everyone deeper into the borough and beyond.

The Curse of the Creative Class

For the development-friendly cachet of artists and gays, some blame—or credit—urban studies theorist Richard Florida for his influential work on the “creative class.” In 2002, the same year that Bloomberg became mayor of New York, Florida published The Rise of the Creative Class and became an economic development guru. He laid out the “Gay Index” and “Bohemian Index” of cities, explaining how these groups would drive economic growth by attracting high-earning professionals into “talent clustering.”

The mayors of several cities heeded his advice. (Florida has since written that his ideas were often “misappropriated and misunderstood” by city leaders.) In the 2012 Financial Times op-ed “Cities Must Be Cool, Creative, and in Control,” Bloomberg wrote that cities must attract creative talent in order to compete for what he called the “grand prize” of tourists and businesses. A competitive city has to be cool, and that means bike lanes, those green veins that stream gentrifiers into low-income neighborhoods, along with art galleries, free Wi-Fi, and public spaces turned into semi-privatized “creativity” zones where hip professionals interact with global brands.

The grand housing stock of Bedford-Stuyvesant has helped make it a new hotbed of gentrification (Photo by Ethel Wolvovitz/Alamy)

Florida’s creative-city idea has its critics. Urbanist Jamie Peck argues that creativity strategies become policy in part because they “work quietly with the grain of extant ‘neoliberal’ development agendas, framed around interurban competition, gentrification, middle-class consumption and place-marketing.” Creativity agendas can deceptively feel lefty, like old Jane Jacobs with her diversity and vibrancy and mixed use. As Peck points out, they “have an apple-pie quality,” generating support while disarming opposition. It’s hard to critique this stuff. Who doesn’t like public art, free Wi-Fi, and other nice things? Bread and circuses are an effective way to control opinion.

When I criticized the High Line, I was attacked as a heretic. And don’t dare complain about bike lanes. Look, I enjoy riding in the bike lanes, but I’m not going to deny that they’re a tool of hyper-gentrification, attracting a certain class of people (to which I belong) and giving a boost to property values, facts that Mayor Bloomberg’s transportation commissioner knew well. Let’s at least engage critically with these things we enjoy. Sometimes a latte is not just a latte.

Is There a Trickle-down Effect?

When assessing urban improvements, we must always ask: Who is it for? Who is it meant to attract and who will it displace? As Florida himself warned in 2002, the impact of high-earning professionals on existing inner-city residents would be to “raise their rents and perhaps create more low-end service jobs.” The classes and, for the most part, the races would not mix. His prediction proved correct. “On close inspection,” he wrote a decade later, “talent clustering provides little in the way of trickle-down benefits.” It’s good for high-skilled professionals, but not for the poor and working class.

Florida has been rethinking his theories, and those city leaders who followed his original advice would do well to listen. In 2016, speaking on the topic of his new book, The New Urban Crisis, he said, “I could not have anticipated among all this urban growth and revival that there was a dark side to the urban creative revolution, a very deep dark side.” He continued, “The urban pessimists have a point. We neglected their point, which is that cities are gentrifying, people are being priced out, displaced from their homes.”

To read more of our reporting on gentrification, see our stories on Bedford-Stuyvesant, Nostrand Avenue, Brownsville and Gowanus.

When the real culprits are the city leaders who serve corporate and real-estate interests, let’s stop pointing the finger at struggling artists and queers. Imagine what would happen to the creative and iconoclastic character of the city—and the nation—without these populations. As Rebecca Solnit wrote, “A city without poets, painters, and photographers is sterile. … It’s undergone a lobotomy.” The system today is such that even the most compassionate young queer poet—imagine her: dedicated to social justice, organizing with Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter, working as a barista in the feminist cooperative bookshop—even she finds herself with little choice but to be a gentrifier, moving to a low-income neighborhood because that’s what she can a afford and her social network is there. And what about me? I’m a white, educated, middle-class professional. If I leave my rent-stabilized apartment, where will I go? Someplace, no doubt, where I will be a gentrifier.

Hipsters: Not the Underdogs

And what of the hipsters? No discussion of today’s Brooklyn can avoid the hipster. Hipster is an old word, but in the book What Was the Hipster? Mark Greif places its contemporary rebirth in the year 1999. Unlike bohemian or punk of the past, hipster, according to Greif, identifies a “subculture of people who are already dominant.” These are not your underdogs carving out a place to breathe free. The modern-day hipster “aligns himself both with rebel subculture and with the dominant class.” The hipster is thus the “rebel consumer” who rebels against nothing, the so-called artist who creates no art.

The author, who wrote his blog under a pseudonym, disclosed his real identity with the publication of his book (Photo by Christopher Schulz, courtesy of Dey St. Books)

The hipsters who flooded Brooklyn (and the entire Western world) in the 2000s might look like bohemians, says Greif, but they are not. They are not anti-authoritarian, like other youth subcultures through history. They drink the Kool-Aid of corporate consumer culture as they adopt a fauxhemian style. In a related essay in New York, Greif noted how hipsters can be found mixing with “anarchist, free, vegan, environmentalist, punk, and even anti-capitalist communities.” The hipster thus infiltrates, appropriates, and commodifies these countercultures, creating elite trends and brands in collaboration with consumer culture.

It was through this process of hipsterization that the New Brooklyn brand was developed and globally disseminated, filling cities with carbon copies of its high-priced coffee bars, rooftop beehives, lumbersexual chic, hyperlocal fetishism, neo-primitive interior design of the rustic and repurposed, curly mustaches and the wax to go with them, all that is twee, all that is “artisanal” and “small batch” and “bespoke.” Places and products are now branded “Brooklyn” across the world. Paris even has an ersatz diner named after Williamsburg’s Bedford Avenue, the fountainhead of hipsterism (and now one of the most expensive retail corridors in America). Brooklyn has become a global consumer movement born from one neighborhood that was “discovered,” became trendy, and then went supernova when the city government and its developer pals swooped in with big plans.

In her book A Neighborhood That Never Changes, urban ethnographer Japonica Brown-Saracino divides gentrifiers into three types: 1) Pioneers, who “celebrate gentrification’s benefits and unabashedly welcome the transformation of the wilderness” as they “seek financial gain”; 2) Social Preservationists, who “work to preserve the character of their place of residence” and seek to prevent displacement; and 3) Social Homesteaders, who are neither Pioneers nor Preservationists, but a combination of the two: “They appreciate authenticity …but gentrification’s cost for longtime residents and their communities are not their central concern.”

All three types benefit from gentrification, and the social preservationist (the category with which I personally identify) also contributes, however unwillingly, to displacement. As Brown-Saracino points out, “preservationists’ presence in a gentrifying area—whether because of their race, relative affluence, or cultural capital—signals to others that it is safe and desirable and, thus, invites further investment by homeowners, businesses, and local government.”

Furthering the Displacement

A middle-class white person in a low-income neighborhood, especially a neighborhood of color, is like a drop of blood in a pool surrounded by circling sharks. We have to do something about the sharks before they get in. Unfortunately, many gentrifiers eagerly chum the waters. They are what we might call gentrificationists, not just celebrating but actively advocating for neighborhood turnover. When they talk and tweet about the amazing new restaurants, and good riddance to that smelly old (fill in the blank), and Dear Starbucks: Can you please open shop in (fill in the blank) because there is no place for blocks to get a good cup of coffee, etc., people are actively working to further the process of displacement. How we talk about the city has an impact.

Dining on the stoop during Spike Lee’s annual block party in Bed-Stuy (Photo by Ethel Wolvowitz/Alamy)

In Spike Lee’s speech, he asked, “Have you seen Fort Greene Park in the morning? It’s like the motherfucking Westminster dog show.” The Daily News went to investigate. Under the headline “Brooklyn Residents Don’t Appreciate Spike Lee’s Rants on Gentrification,” they interviewed newcomers to Fort Greene, all out walking their “fancy pooches.” They talked to one 25 year year old with an English Springer Spaniel she’d named Hudson, presumably after the river. A farm-to-table restaurant owner, she’d just moved to Fort Greene from the Hamptons. She told the paper, “I don’t see a negative to cleaning up a neighborhood. … I think it’s a creative bunch of people doing interesting things. It’s all good intentions.” Had she never heard about the road to hell and its paving stones?

Another young person walking her miniature poodle said, “people have the right to live wherever they want to live.” And a third, a jewelry designer and dog walker from Toronto, agreed that the perks of gentrification far outweigh the drawbacks. “I benefit from it,” she said. “I can have a decent cup of coffee.”

Like these pioneers, many people didn’t like what Spike Lee had to say. He was too angry, said online commenters and journalists. They called him “arrogant” and didn’t like the fact that, like television’s George Jefferson, he had moved on up to the Upper East Side. He was a wealthy hypocrite who abandoned Brooklyn, they said, and besides, “White people were there first.” In an op-ed for the Daily News, journalist Errol Louis made some good points about Lee’s role in the gentrification of Brooklyn, including flipping several properties and participating in the marketing of “Absolut Brooklyn” vodka.

There were definitely conflicts that Lee did not address during that Q&A at Pratt, but that does not fully explain the angry, racially toned backlash he received, and the fierce pro-gentrification cries that swirled around him. Plenty of other financially successful New York artists had railed against gentrification—David Byrne of Talking Heads, whose net worth is estimated at $45 million, even used the word “fuck” in a rant against the urban rich—and they didn’t get such backlash. But they weren’t black people expressing anger about white people moving to Brooklyn, the ultimate urban frontier of the 21st century.

From the book VANISHING NEW YORK: How a Great City Lost Its Soul, by Jeremiah Moss. Copyright ©2017 by Jeremiah Moss. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

The Blossoming of Bed-Stuy: Is Gentrification Racist?

Of all the changes I’ve witnessed in Brooklyn since I settled in the borough over 30 years ago, none has been more surprising than the blossoming reputation of Bedford-Stuyvesant. For decades after 1950, in the minds of outsiders, and many residents as well, Bed-Stuy’s nickname “Do or Die” captured the spirit of the place. It was a neighborhood of hopeless black poverty, mean streets, meaner housing projects, and a homicide rate that had reporters reaching for war metaphors. Now, according to the media’s coverage of style, real estate, and food, Bed-Stuy is the next Park Slope and Williamsburg. It is becoming the latest destination for young professional and creative-class whites on their ceaseless prowl for appealing housing, lively walkable streets, and express subway lines to Manhattan. Inevitably, good coffee, Danny Meyer–inspired restaurants (one, with the winking name Do or Dine, was known for its foie-gras doughnuts before it closed in 2015 and reopened as a bar called Do or Dive), and prenatal yoga classes have followed close behind.

Besides its profile of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Hymowitz’s book charts the comeback of neighborhoods including Park Slope, Williamsburg and Sunset Park

In some circles, changes wrought in neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy and other black communities like Columbia Heights in Washington, D.C., or Oakland, Calif., are routinely described as ethnic or racial cleansing, or, more bluntly, “white people stealing shit.” In a famous 2014 rant, the filmmaker Spike Lee railed against the white newcomers in the once-black Brooklyn neighborhood of Fort Greene, accusing them of being part of a “motherfuckin’ Christopher Columbus syndrome.”

But a closer look at Bedford-Stuyvesant reveals the usual drama of white oppressor meets black victim/professional meets working stiff/yuppie meets homeboy to be a cartoon picture of a much more interesting story of economic, social, and racial transformation. No one would deny that the blighted black area has seen both an influx of white professionals and creative types as well as the sort of designer cafes and restaurants that keep them well lubricated and content. Talk to locals and look closely at the census and crime data, though, and you’ll find that gentrification’s familiar tensions around class and inequality are also intra-racial, reflecting the rise of a dynamic new black class, on the one hand, and the persistence of a ghetto underclass, on the other.

Blacks Come to Central Brooklyn

To understand the disputed territory that is Bed-Stuy, one of the fastest-growing neighborhoods in Brooklyn, the first thing to appreciate is its location. Bedford-Stuyvesant sits near the middle of the borough, abutting Williamsburg to the north, Clinton Hill and Fort Greene to the west, Crown Heights to the south, and Bushwick to the east. Those once-poor and working-class neighborhoods are now in flux as professionals, artists, managers, and nonprofit employees (most of them white) are not only priced out of Manhattan but of the proto-yuppie neighborhoods of Park Slope and Cobble Hill and hipster meccas like Williamsburg as well. Bed-Stuy was bound to succumb to the educated-class invasion, if for no other reason than it is near these other rising areas and, not to be forgotten, it has excellent subway connections to Manhattan.

The area’s biggest draw, however, is its legendary brownstones. Nineteenth-century architecture is to Bed-Stuy what oil is to Saudi Arabia. In that era, a growing German and Dutch upper middle class, wanting to escape the grimy tenement districts of Manhattan, began to build homes in the once-rural village of Bedford. Bed-Stuy’s “starchitect” of the time, Montrose Morris, built the first apartment building in Brooklyn, the Alhambra, at the southern end of the area in 1889. It was a risky venture, since the aspiring middle class tended to equate apartments with poverty-filled tenements. But Morris’s extravagant Romanesque and Queen Anne pile—think nine-room apartments with maids’ quarters and a croquet court in the building’s garden—was far from that.

A handsome row of houses on Decatur Street in Stuyvesant Heights Historic District, established in 1975 (Photo by Smallbones/Wikipemedia Commons)

Morris was part of a building spree that resulted in block upon block of single-family homes with a riot of intricate masonry that still delights: Romanesque arches, bays, Byzantine columns, Queen Anne-style pediments and gables, terra-cotta tiles, carved mahogany doors, castle turrets, stone swirls, cupids, flowers, and grotesqueries of animals and human faces. Metalworkers added wrought-iron fences and gates. Churches and community groups were plentiful. Add newly planted shade trees, and you had the infrastructure and civic energy for urban living at its best.

Bedford and nearby Stuyvesant Heights were not to remain so fine for very long. Between the two world wars, the original German upper-middle-class homeowners—manufacturers, merchants, and brokers—took off for the suburbs, to be replaced by working-class Jews, Italians, Irish, and others. The area’s brownstones were already showing their age, and so was the area’s reputation.

By comparison with other northern cities, the shift in Brooklyn’s racial geography was late in coming. The great migration northward after the Civil War had already given Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Manhattan’s Harlem a substantial black population by 1920. Brooklyn’s black population grew more slowly. Until the 1930s, blacks made up less than 1.4% of the borough’s population. There was no official Jim Crow in Brooklyn, but discrimination shadowed the newcomers through their daily lives. Segregation was commonplace in hospitals and schools; movie theaters refused to sell orchestra seats to black customers.

Bed-Stuy’s racial identity shifted more notably during the Depression. In 1936, the A subway line was completed, giving Harlemites easy access to their brethren in Kings County. They liked what they saw in that small settlement in Bedford. The houses around Bedford and Stuyvesant Heights were superior and the neighborhood far less packed than their home district in northern Manhattan. The Harlem and Jim Crow refugees may have seen in the area’s brownstones a luxury that they could never afford in Manhattan. The established white residents, on the other hand, saw obsolete, fraying structures no longer suitable for their modernizing lifestyle. The more restless of them headed off to newer housing developments in Flatbush.

The Depression brought about another change—a federal program that would eventually help drag Bedford-Stuyvesant and other minority communities around the country into desperate straits. In the early 1930s, the Roosevelt administration, attempting to head off mass foreclosures and bank failures, created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), whose main purpose was to subsidize imperiled mortgage holders. To gain more information about the problem, they surveyed 239 cities across the country and created “residential survey maps.” The surveys rated neighborhoods based on a number of characteristics: the age and type of housing and residents’ occupations and incomes, as well as the number of foreign-born residents and blacks. Most momentously, it created maps ranking neighborhoods from A, for desirable areas, to D, for risky ones. It’s not clear how widely disseminated the maps were—they came to public attention only in the 1970s, when they were uncovered by historian Kenneth Jackson. But their color coding—A areas were colored green, B and C in blue and yellow, and D in red—gave birth to the term “redlining.”

A Spike Lee block party in Bed-Stuy in 2015 (Photo by Ethel Wolvovitz/Alamy)

The long-term consequences of redlining and the exploitative lending practices following in its wake for aspiring black homeowners like those of Bedford-Stuyvesant—and their descendants—would turn out to be calamitous. However, if race was the guiding principle behind the HOLC’s rankings, it’s hard to see it in the 1937 Brooklyn map. Much of Brooklyn was redlined, including parts of Park Slope, which at the time was more than 90% white. Redlined Bed-Stuy itself was about 12% black in 1930, about the time when the maps were first being researched. It’s possible that the HOLC was alarmed by that 12%, but it’s also the case that lenders and officials at the time didn’t care for the white ethnic groups in the neighborhood either. The agency shared widespread contemporary assumptions about the limited material value of older, urban, and ethnic neighborhoods as well as racial suspicion—especially, as was the case during the Depression, when people didn’t have the funds to renovate outdated plumbing and crumbling stonework. Investors aren’t looking for ways to lose money, after all.

Indeed, over the next decades, many brownstones already scarred by the Depression went into deep decline. Struggling residents, white and black, stripped gracious parlors and decoratively plastered bedrooms to create rooms for boarders, as windows rotted and stone washed away. By the 1940s, frequently panicked into selling at a discount by “blockbusting” real estate agents, the remaining Jews and Italians packed up and left for Long Island and other points in Brooklyn and Queens. By 1950, Bed-Stuy was already 50% black. Ten years later, it was 74%.

The Ghetto and the Black Middle Class

By the mid 1960s, with Bedford now merged with next door’s Stuyvesant Heights, the community was bulging at its seams. Some 450,000 residents, the size of the population of a medium-size American city, were crammed into less than three square miles. It was the most populous neighborhood in Brooklyn and had one of the largest concentrations of African Americans in the U.S., second only to South Chicago. As in Chicago, the city government turned its back: garbage pickup was listless, at best; and the schools were dilapidated and disorderly.

The large majority of Bed-Stuy residents at the time were high school dropouts. During World War II, the Brooklyn Navy Yard had provided jobs; Local 968 of the longshoremen’s union had a membership of 1,000 African-American men (though union solidarity did not prevent blacks from being last hired, first fired). After the Navy Yard was decommissioned in 1966, those jobs were gone and Bed-Stuy’s social decline accelerated. Already 36% of children were born to unmarried mothers, a number that would continue its relentless rise into the 21st century. Rates of venereal disease and infant mortality were among the highest in the nation. Juvenile delinquency, gangs, and heroin added to the misery. Merchants on the once-vibrant Fulton Street closed their doors; holdups and muggings were chasing away customers and making employees fear for their lives.

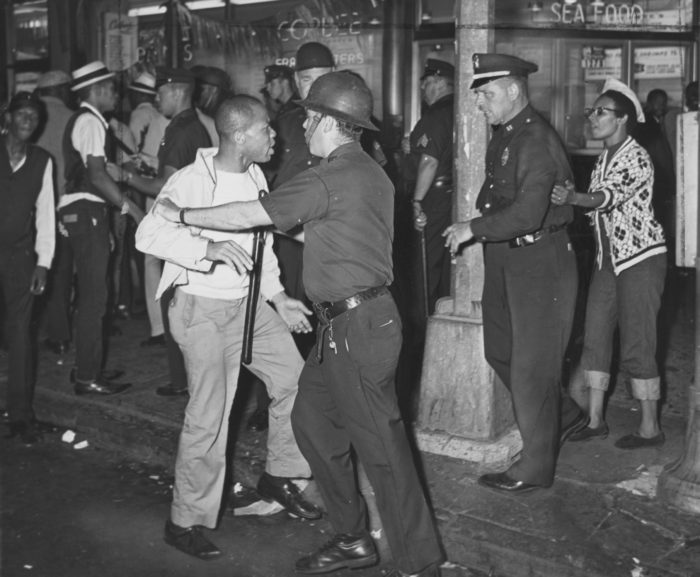

A confrontation between African Americans and police with nightsticks at Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue during the Bedford–Stuyvesant riot of 1964 (Photo by Stanley Wolfson/Library of Congress)

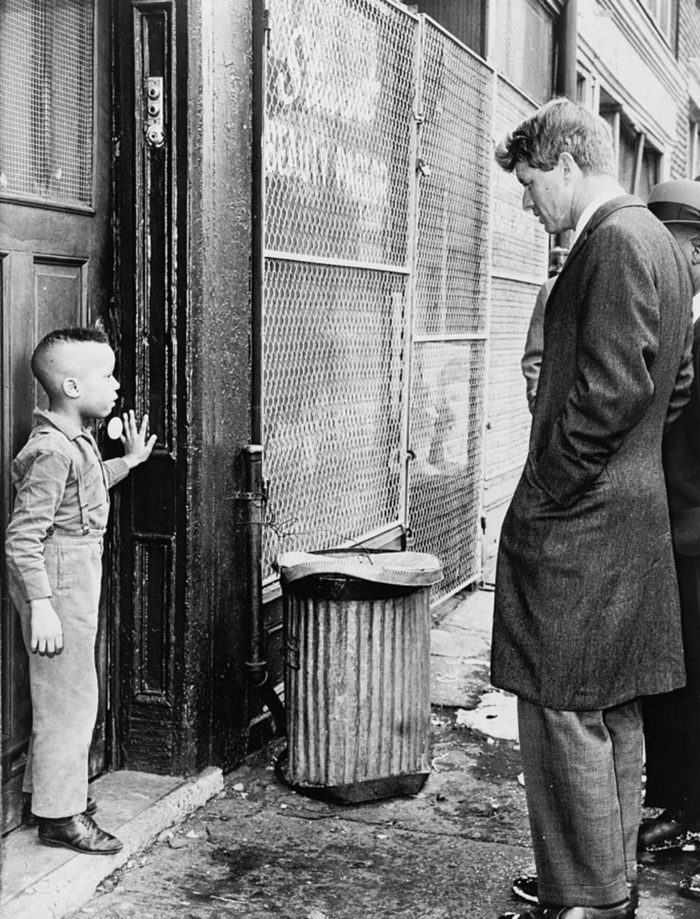

By the 1960s, the blight of Bed-Stuy brought the neighborhood a national reputation as a poverty-and-crime-stricken black ghetto. In July 1964, Harlem was torn by riots after a white police officer shot and killed a 15-year-old black youth, James Powell. Two days later, the flames spread to Bed-Stuy, where an estimated 4,000 rioters ransacked hundreds of local stores and pelted police and fire fighters with bottles and bricks. Those days of chaos, which would flare up sporadically in “long, hot summers” through much of the 1960s, led New York’s newly elected senator Robert F. Kennedy to take a walking tour of the area. In 1966, journalist Jack Newfield, who accompanied the senator, described their excursion as “filled with the surreal imagery of a bad LSD trip.” Kennedy gathered a group of high-powered businessmen and Bed-Stuy community leaders to create the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corp., the first community-development corporation in the country.

Black poverty, crime, drugs, underclass misery: that’s the picture that most outsiders have had of Bed-Stuy since the 1960s—until very recently. But there was always another Bedford-Stuyvesant whose considerable strengths had the potential to serve as the foundation for an eventual revival. Even as whites and banks began to flee in the middle decades of the 20th century, the neighborhood had a tight-knit, neighborly working-class spirit that lingers in the local ancestral memory and remains a source of local pride. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, black teachers, mail carriers, firefighters, and nurses lived on those fraying blocks. Many of them, through a mixture of luck, hard work, and penny-pinching were able to buy and live in those precious brownstones. Some would hand down their houses to their children and grandchildren, who continue to live there today. Compared with other poor communities like Harlem, where renting was the norm, Bed-Stuy had relatively high levels of homeownership. Even in the 1960s, after decades of neighborhood downward mobility and damage caused by an abundance of negligent absentee landlords, nearly 23% percent of area buildings were owner-occupied, according to a study by the nearby Pratt Institute; another 10% percent had owners living nearby.

Sen. Robert F. Kennedy discusses school with Ricky Taggart on Gates Avenue in 1966 (Photo by Dick DeMarisco/World Telegram & Sun/Library of Congress)

The combination of those enticing brownstones, human-scale streets, and neighborly residents nourished a civic orientation that carried at least some of Bed-Stuy through miserable times. The neighborhood’s Southern blacks had brought with them not just hopes of a better life but the habits of friendly, slow-moving, small-town living. Bed-Stuy residents still boast about blocks where folks always say “good morning” to passersby and warm evenings where residents sit on the stoops of their homes, passing the time and watching children playing on the sidewalks. Churchgoing black homeowners remained a resilient, family-oriented group. A former resident, 86-year-old Ulric Haynes Jr., is old enough to remember the block when it was half white. His observations of Bed-Stuy evoke an alternate universe compared with the ’hood of popular imagination: “All the black kids on the block went to college. And I do mean all, though I can’t say that for the white kids. On the part of the black families on that block, there was a conscious effort to improve one’s self. I would attribute our feeling to a kind of immigrant zeal. We all knew, even those who came from the American South, that we had to work hard—not just to make a living but to make a place for ourselves in American society. And the white kids in the neighborhood didn’t have that feeling, that zealousness.”

“We were very much a group of strivers,” he concludes. Haynes is understating, at least in his own case: his career as a diplomat, lawyer and educator included a term as U.S. ambassador to Algeria.

Throughout the decades that Haynes and his peers were growing up, Bed-Stuy was alive with civic activity: there were homeowners’ associations, African American–run banks, block associations, food co-ops, and house tours. After years of lobbying, local strivers gained landmark status for the Stuyvesant Heights historic district in 1971. The Bedford-Stuyvesant Neighborhood Council lobbied for better sanitation, bus, and subway service.

Bed-Stuy’s African American population built the neighborhood into the cultural center of black Brooklyn, which, by the 1950s, had expanded into Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Brownsville, parts of Bushwick, and Williamsburg. That culture may not have had the national reputation of the Harlem Renaissance, but it was nonetheless a source of solidarity, pleasure, and commerce that still shapes the local population’s sense of itself. By the 1940s, Bed-Stuy had dozens of restaurants and movie theaters, including the 2,500-seat Brevoort, one of the largest in New York City, which made a specialty of black-directed films starring black actors. According to historian Clarence Taylor, though whites owned many of the local establishments, black-owned businesses were commonplace. In the 1950s, jazz greats Freddie Hubbard and John Coltrane played at local clubs; Dinah Washington and Carmen McRae performed there as well.

Even during the dark, crack-filled days of the 1980s, black performers sparked feelings of local pride. By setting some of their most memorable work on the blocks of Bed-Stuy, Spike Lee and Chris Rock helped the area to usurp Harlem as the center of black energy and style in the American consciousness. By the 1990s, Bed-Stuy had become hip-hop’s Nashville, the birthplace and inspiration of Lil’ Kim, Notorious B.I.G., and the rapper-impresario Jay-Z, who was born Shawn Carter, the bard of the gun-tormented Marcy housing projects, equally well known for his roles as Beyonce’s husband and entrepreneur.

The New Bed-Stuy

Given this history, it’s not hard to see why some locals would glower at the white or biracial couples pushing wooden-toy bedecked strollers, or bike riding, or parent-dependent musicians and art students moving into their territory. There’s no question about it: the newcomers have helped make $2,000-a-month one-bedroom apartments and $2 million houses the new normal in the once cut-rate neighborhood. Wittingly or not, they’ve been party to the departure of low-income locals from apartments that they called home during a time when the rest of the world wanted nothing to do with either them or their neighborhood. A lot of poor renters have been reduced to scouting the ads in the far less richly endowed Brooklyn neighborhoods of East New York and Brownsville. Bed-Stuy saw a 633% increase in the white population between 2000 and 2010; according to the New York Times, that’s the biggest increase of any racial or ethnic group in any New York City neighborhood. As of 2010, the share of black Bed-Stuy residents had shrunk from 82% in 2000 to about 65%.

Still, Bed-Stuy’s fortunes do not fit a simple story of gentrification’s white colonialism. For one thing, Bed-Stuy was becoming less black in part because of a rising number of Hispanics; their portion of the population increased by 17% in the decades between 1990 and 2010. For another, there were so few whites in 2000, that while the white influx was huge, percentage-wise, they still added up to only 15% of the Bed-Stuy population in 2010. Moreover, the large majority of those whites are clustered in two census tracts in the northwest corner of the neighborhood, abutting Williamsburg. Walk along those streets, and you’ll jostle neither white hipsters nor briefcase-toting lawyers but bewigged women in long skirts pushing double strollers to kosher food establishments past new apartment buildings with staggered balconies where Jews can build their Sukkoth huts. More than yuppies, the Hasidim are the white newcomers—though “newcomers” seems inaccurate, given the Jewish presence in the 1920s and 1930s.

A mural of the late rapper The Notorious B.I.G., who grew up in the neighborhood (Brian Harkin/The New York Times/Redux)

Also muddying the stereotypical gentrification story are the numerous signs of black success. Older, longtime black homeowners who held on through the worst times are now cashing in. Many of them are moving to greener pastures. In 2006, Claire Hussain, a half-Bangladeshi, half-Irish woman and her Irish husband purchased a three-story brownstone on Madison Street between Tompkins and Throop from a couple in their mid 60s who had lived in the house for 35 years. After vetting Claire and her husband to be sure that they were going to be suitably respectful of their beloved house, the owners bought a large new home with a pool in Georgia, where their daughter and her family lived. Clare is now vice president—and the only non-black member—of her block association. She and her husband have made friends with many upwardly mobile couples with young children on nearby blocks. “They are almost all black or mixed-race,” she says. Most have moved from other parts of the country, but more than a few are returning sons and daughters who grew up in the ’hood.

In fact, black college-educated professional men and women, or “buppies,” as they are sometimes called, are the underappreciated engine behind Bed-Stuy’s gentrification. In researching his book There Goes the ’Hood, Lance Freeman found a similar trend in both Harlem and Clinton Hill. “By the 1990s,” Freeman writes, “Fort Greene/Clinton Hill was a mecca for black creative types and entrepreneurs” who dismissed the suburban aspirations of previous upwardly mobile groups. They are now drawn to what Freeman calls the “neo-soul” aesthetic and culture of Bed-Stuy. Between 1990 and 2000, the percentage of households earning over $50,000 a year went from 12% percent to 28%, while the number of households earning over $100,000 went from 947 to 3,293 (a 350% increase). The number of owner-occupied buildings soared 633% in the same ten years. Yet, unlike the large white increase in the following decade, the racial composition of the neighborhood hardly changed.

This new black gentry—and their white counterparts, for that matter—often take their business to one of several pockets of gentrified commerce in the area, much of it black-owned and black-run. Bed-Stuy suffered badly from the subprime-mortgage crisis; the area had among the highest rates of foreclosure in the city. Still, even during the recession, new cafes, bakeries, and lounges were opening, especially along a commercial corridor taking shape along Classon Avenue and the four-block stretch of Lewis Avenue between Halsey and Decatur. Walking south along Lewis Avenue, at Halsey, you come across Saraghina, a brunch and pizza café and a perfect example of gentrification, Bed-Stuy-style. Though owned by two Italians, Saraghina couldn’t be further in spirit from Sal’s, the classic Brooklyn family-run pizza joint in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, with its pictures of Joe DiMaggio and Frank Sinatra on the walls. Instead, Saraghina seems to have been imported straight from Portlandia. One weekday morning around 11, I got to the meandering white painted space, with retro icebox doors, vintage glass bottles, and long picnic-style tables, to find three black women in their 20s and 30s and another older, mixed-race couple sipping coffee as they worked on their laptops and checked their phones. One of the three freelancing women was a yoga teacher who grew up in Ohio; another, a media producer recently moved from Michigan; and the third, a food consultant in the area who runs a wholesale distribution coop of food and groceries with 50 or 60 members.

Neighbors mingle along Jefferson Avenue between Marcy and Tompkins (Photo by Mattia Insolera/LUZ/Redux)

The food consultant, Melissa Danielle, is a sharply observant, third-generation Bed-Stuy resident whose maternal great-grandparents arrived in the thriving black Weeksville community in the 1920s. She herself grew up in her mother’s nearby brownstone. She remembers first noticing signs of gentrifica- tion in the late 1990s in Fort Greene, where she went to high school, and a bit later in Bed-Stuy, when a new population of twenty- and thirtysomething black men and women moved back to the area from college or time spent abroad. “You want to re-create the experience you had in college,” she explained. “You socialized in bars and cafes; you want something like that where you live.” Contra the conventional wisdom, “It was black folks who opened up the first $3 coffee shops—and black people who com- plained about it.”

Anthony Williams, co-owner of the Therapy Wine Bar, one block down from Saraghina, tells a very similar story. A Bed-Stuy native, Williams opened up the bar after he and his partner noticed that in order to sit for a while and sip a good pinot noir, they had to venture far outside the neighborhood. They found a space—one that hadn’t been rented since 1985—and started renovating it in the upscale style that they had seen during their meanderings. Therapy has stylish, small glass globes hanging over its long, polished bar and, on the exposed brick wall opposite, framed album covers of jazz and hip-hop artists. Black music—jazz, soul, and rap—was a big part of the plan for the bar. (Sometimes they play the albums of Santigold, a local hip-hop star, brownstone owner—and 1997 Wesleyan graduate.) Williams says that his clientele comprises upwardly mobile blacks, mostly college-educated, many from the Midwest and some Bed-Stuy returnees. He has been surprised by the number of tourists stopping in for a drink. They may be staying at the nearby Akwaaba Mansion (a bed-and-breakfast opened in 1997 by an editor at Essence who is now owner of four other B&Bs between D.C. and the Jersey shore) or boutique hotel The Brooklyn, which opened in 2015 on Atlantic Avenue.

On the next block of Lewis, Peaches, fast growing into a neighborhood franchise, is a perfect distillation of black and white strains of gentrification. Peaches is jointly owned by Craig Samuels, a black man, born and bred in Bed-Stuy, who trained at the haute Philadelphia restaurant Le Bec-Fin; and Ben Grossman, white and from the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. The food reflects the hybrid nature of their establishment no less than the owners: on the one hand, Brooklyn foodie-style lists of sustainable sources on the menu; on the other, Southern favorites like grits and jambalaya. Other black-owned Lewis Avenue establishments include Brooklyn Beso, serving a combination of Southern and Latin American fare; and Emeline’s, a diner named after the Bed-Stuy native owner’s grandmother, who grew up in Weeksville. There are many others: Rustik Tavern, Bed-Vyne Brew, Bedford Hall, Essence Bar, Vodou Bar, and the Black Swan, in a former auto-repair shop, all owned by young black entrepreneurs, many of them children of Bed-Stuy. One 2014 survey found 33 new retail establishments.

Food vendors at a street festival on Atlantic Avenue (Photo by New York City/Alamy)

For all the lively commerce of Lewis Avenue and the encouraging signs of black upward mobility, tensions do mar the changing Bed-Stuy. White gentrifiers sometimes raise hackles when they tell longtime residents that the neighborhood is “coming back” or when they frown at the locals’ “stoop culture.” As in Park Slope, stoops—and noise levels—remain a cultural flashpoint between newly arrived whites and locals. Given that gentrifiers are almost always in their 20s and 30s, there are generational tensions as well. Danielle says that a lot of old-timers are wary of giving liquor licenses to restaurants or upscale bars. “Why does a restaurant need a bar?,” they ask with annoyance. “They still think of bars as hangouts for drug dealers and down-and-out winos,” she says.

The Persisting Ghetto

But the biggest problem facing the area is not class and racial tension; it’s the fact that many parts of Bed-Stuy still merit the term “ghetto,” with all the problems that term implies. The numbers make alarm about gentrification seem beside the point. Over 30% of the population is below the poverty line; that represents a decline from 35% in 2000, but it’s still very high by regional standards. An April 2012 report from the Citizens’ Committee for Children put the percentage of poor children in the area at a catastrophic 47%. Bed-Stuy families with children under 18 had a median income of about $28,000 in 2010, compared with a citywide average of about $61,000. There is an obesity rate of 63%, seven percentage points higher than the city as a whole; reported levels of child abuse are twice as high as other parts of NYC. In 2012, unemployment was nearly 17%, also well above the rest of Brooklyn and the city as a whole. Fair-trade coffee shops and designer pizza joints are not going to do much to change that.

Nor are gentrifiers likely to be able to help the educational prospects of the area’s children. Fewer than 18% of third-graders passed the Common Core reading test; that’s about 12 percentage points worse than for the whole of Brooklyn. An earlier report described the area’s middle schools as “in a crisis state.” The community landmark Boys and Girls High is among the bottom 5% of schools in the state in terms of achievement.

The most important threat to the neighborhood’s well-being is crime. Articles on Bed-Stuy nearly always tout the large percentage drop in crime. They’re right to do so. The numbers are astounding. Murders in the 79th Precinct went down by 67% between 2010 and 2016. But the truth is, improved or not, Bed-Stuy crime rates remain among the worst in the city. On chat boards, commenters draw elaborate maps for people thinking of moving to the area, detailing the best routes to shopping areas and subways, as well as lists of no-go zones. Don’t settle too far from the subway stop, they advise. You’re safe about two blocks north, but don’t go west. Not after ten at night. And so on. Bijoun Jordan, an African American high-school teacher who grew up in Georgia, and his wife, a publicist, were enjoying the Bed-Stuy vibe: “I would go to random concerts on Fulton. We lived above Peaches Hot House [owned by the people at Peaches on Lewis Avenue], and I would go there to grade papers or have a drink.” But when the couple was awakened by shots one night in 2014, shortly after their daughter was born, they wasted no time. After studying crime statistics in nearby neighborhoods, they decided to move to Kensington, a quiet neighborhood south of Prospect Park. “We were paying the rent of an upper-echelon neighborhood,” he says resignedly, “but had none of the security.”

In a landmark study, William Julius Wilson argued that the civil-rights movement of the 1960s had one tragic unintended consequence for urban blacks. It gave the middle class the ability to exit black ghettos, leaving behind, as the book’s title puts it, the truly disadvantaged. In Wilson’s telling, the middle-class departure concentrated the ills of poverty into a single, hopeless geographical space. The black middle class had created pockets of relative stability and normalcy within the sorrowful ghetto. Not only did teachers and accountants patronize local businesses, Wilson wrote in a 2012 afterword of his book; they “reinforced societal values and norms” and gave the poor a chance to “envision the possibility of some upward mobility.” Now a black middle class is returning to some of the very neighborhoods that their parents either escaped or aspired to escape.

But the ability of the black educated class to inspire the down-and-out of today’s Bed-Stuy partly rests on a notion of racial solidarity that may not hold up in the 21st century. In Black on the Block, her book on black gentrification in the North Kenwood-Oakland area of Chicago, sociologist Mary Pattillo McCoy describes the “divergent class interests” that confound widespread assumptions of a unitary “black community.” For the prodigal black gentrifiers as well as the young educated who grew up there, living in the whitening ’hood inevitably leads to spells of existential vertigo. “Walking by the Marcy projects with a bag full of Trader Joe’s groceries,” as one Bed-Stuy blogger describes her life, has a way of exploding popular ideals of a single “black identity.” The dilemma is not entirely new; other upwardly mobile groups—immigrant Jews, Italians, and Irish—have struggled with a similarly split self. In their case, class identity has ultimately submerged race identity.

That dynamic may well play out differently among blacks. But though complaints about perceived racism in the workplace and suspicion about white motivations remain fairly common, black gentrifiers tend to be a cosmopolitan group. They are generally at ease when a white English professor or nonprofit administrator moves into the apartment upstairs. The same cannot be said about either Bed-Stuy’s old-timers who came of age during the days of black power or the younger activists. “You can’t just come in when people have a culture that’s been laid down for generations and you come in and now shit gotta change because you’re here?” said Spike Lee in his 2014 diatribe. “Get the fuck outta here … How you walking around Brooklyn with a Larry Bird jersey on? You can’t do that. Not in Bed-Stuy.” If you think about it, Lee’s comments are troublingly reminiscent of the way Irish and Jewish Bed-Stuy residents might have sounded in the 1930s.

Lee’s bunker mentality isn’t likely to triumph over the forces of economic and social change bringing about gentrification. For at least four decades, white was the dominant color of Bed-Stuy; black has been the primary color only a bit longer than that. Now, once again, things are changing. “You’ve got the most unexpected, diverse people moving into the neighborhood now,” Morgan Munsey, a Bed-Stuy native and real estate agent, told the New York Times. “I’m getting a lot of Europeans, and actually lots of Germans.” Those were the very people, Munsey muses, who built Bed-Stuy in the 19th century. “But you still have your old-timers and African-American families who’ve been here for generations.”