A Tale of Two Dwellings in the Flood Zone of Red Hook

New York is a city where lofty wealth can live side by side with grueling poverty—and few neighborhoods illustrate that split personality better than Brooklyn’s Red Hook. Once the busiest freight port in the world, by the 1980s Red Hook was one of the poorest neighborhoods in the U.S., cut off from the rest of New York by the water that borders it on three sides, and by the Gowanus Expressway to the east. Yet while the 21st century has witnessed a Red Hook renaissance—with multi-million-dollar condo sales making Red Hook at least temporarily the priciest neighborhood in Brooklyn—the area still has a poverty rate of nearly 50%. More than half of the neighborhood’s population lives in the Red Hook Houses, the largest public housing project in Brooklyn and one of the oldest in New York.

In the aftermath of Sandy, residents of the Red Hook Houses were without power for weeks. Tameka Evans, with her two-year-old son, used her gas stove to keep the apartment warm (Photo by Gregory P. Mango/Polaris)

Those houses were hit hard by the flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Power was knocked out in most of the buildings for some three weeks—significantly longer than other parts of New York that lost power during Sandy—and running water was out for almost as long. Because storm damage to the New York City Housing Authority’s buildings was so widespread, the agency struggled to get utilities back online. The Red Hook Houses had no heat for weeks, including during nights when temperatures dipped into the 30s. Water damaged the roofs and walls of the buildings, leading to significant mold growth. Even after utilities were said to be restored to the Red Hook Houses, some residents reported intermittent failures for the rest of the year.

Part three of a three-part special report from The Bridge

The Red Hook Houses were hardly the only buildings in the neighborhood badly damaged by Sandy. Floodwater, after all, doesn’t take income into account–only elevation–and barely a block in low-lying Red Hook remained untouched after the storm. But walk around much of Red Hook today, and you might have little idea that Sandy ever happened. The neighborhood, long isolated from the rest of Brooklyn’s boom, has taken flight, with a fleet of new waterfront condo buildings and townhouses on the way.

Among them is 160 Imlay, where the Italian developer Estate Four has converted the decrepit New York Dock Co. building into what will be some of the most expensive condos in the neighborhood. The development is the convergence of old and new Red Hook—a long-abandoned waterfront building that dates to Red Hook’s glory days as a major freight port, now transformed into luxury residences for buyers willing to spend in the seven figures. What those two Red Hooks have in common is water. 160 Imlay faces the Atlantic Basin, a man-made harborage that once hosted ships by the hundreds. In Red Hook’s port days, that location mattered for its proximity to the water as a highway. Today its value is in water views for condo residents.

The Red Hook Houses are the largest public-housing project in Brooklyn, with about 6,000 residents (Photo by Timothy Fadek)

The Red Hook Houses, while set back from the shoreline, have roots in the neighborhood’s maritime past as well—the buildings were first constructed in the 1930s for the families of Red Hook dockworkers. But today the water is something to be defended from. And in the years since Sandy struck, New York has taken steps to strengthen the Red Hook Houses and other vulnerable public housing projects from future floods. (Ten percent of New York’s public-housing projects and more than 80,000 residents were affected by Sandy, causing over $3 billion in damage.)

As part of a nearly $3 billion grant from the Federal Emergency Management Authority—the biggest in the agency’s history—last month September the city Housing Authority broke ground on a $63 million project to replace all 28 roofs at the Red Hook Houses. Eventually the city agency will spend almost $550 million in total to harden the buildings against future floods, including installing electrical rooms and boilers above the level of a 100-year-flood, as well as putting in backup generators. “By 2021, we’ll be leaving this site stronger and more prepared for future storms,” promised Shola Olatoye, the Housing Authority CEO, in kicking off the roof-repair phase of the project.

The view across Buttermilk Channel from a condo at 160 Imlay (Image courtesy of Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Sandy’s damage to the Red Hook Houses and to other public-housing projects was so severe not just because of their location, but because much of the city’s public-housing stock was rundown well before the flood. While the Red Hook Houses will come out of the Sandy rebuild tougher and more resilient than they were before, how many times can New York—or any city—afford to embark on multibillion-dollar reconstruction? It’s hard enough to keep public housing running on sunny days. What will happen if, as some studies predict, Sandy-level catastrophes begin hitting New York as often as every five years?

The well-heeled residents of new Red Hook developments like 160 Imlay might wonder too. The architects behind the project have said they’ve taken Sandy and future flooding into account, raising mechanical and electrical equipment above the flood level, filling in the basement—particularly important because of Red Hook’s shallow groundwater—and flood proofing other vulnerable areas, including the water-heating system. That’s partially the advantage of new construction—the city mandates that new or significantly renovated construction take flood hazards into consideration.

Their waterfront location may seem vulnerable, but post-Sandy buildings like 160 Imlay will be in a better position than some others to weather the next storm. “The water can come sloshing through the building, and the electrical equipment will be fine,” says Patty LaRocco, an agent at Douglas Elliman Real Estate and the broker for 160 Imlay. “It’s 18 feet above sea level.” She also notes that the development will benefit from a FEMA-funded flood wall that is planned for the Atlantic Basin. “This building will be the last building standing if anything happens.”

What’s happening at the Red Hook Houses and at 160 Imlay demonstrates that there are practical steps that can be taken to protect New York property—at the poorest level and at the richest—from more frequent and devastating floods. It won’t keep the neighborhood safe forever, not with climate change raising sea levels by feet in the decades to come, not when all of Red Hook could end up submerged someday. But it’s a start, as Red Hook’s relationship to the water changes once again.

Make an aerial visit to Red Hook via our drone-powered tour of the neighborhood

The Remarkable Recovery of Business in Red Hook

On that blustery October afternoon, a few days before Halloween 2012, the forecasts were grim. Mandatory evacuation orders were in place for nearly the entire neighborhood of Red Hook, Brooklyn. With newscasters and city officials warning that Hurricane Sandy could bring historic devastation, business owners grabbed the last of what they could and evacuated by the 5 p.m. curfew.

Some stayed to ride out the storm. As she watched the water lap over the shoreline, Tone Balzano Johansen, owner of the iconic bar, Sunny’s, went down to the basement to put valuables on a table. She recalls that for a moment, it was eerily calm. Around 9:30 p.m., at high tide and with a full moon, the sea lifted. A storm surge of more than 14 feet sent a cascade of seawater rushing into Red Hook.

As Johansen worked in the basement, she heard a loud “pop.” A window shattered. Water gushed in with a ferocious velocity. “I had to get ahead of it. I could see the electric meters right there. There are two dangers: you can be electrocuted and you can get trapped. Zapped and trapped, and you’re done. ” She ran up the stairs. “It was like I was flying. I very narrowly made it out of there.”

Ben Schneider, co-owner of The Good Fork restaurant

Dozens of small businesses near the harbor filled with saltwater. The surge receded quickly, but the devastation was done. Many companies lost nearly everything in the fast-moving flood: computers, trucks, food, furniture, office equipment, documents, a grocery store’s vast inventory. Most did not have flood insurance and those who did fought for scant payouts. Four inches of snow fell three days later, and parts of the neighborhood were without power for weeks.

Part two of a three-part special report from The Bridge

The night of Hurricane Sandy launched an arduous, and costly, cleanup for businesses throughout Red Hook. As the fifth anniversary of Sandy approached, The Bridge talked with owners and managers about the quick decisions they had to make that night, the damage they found the next day, the lessons learned, and preparations for future battles with the sea.

Things Began to Float

Days before the storm hit, employees at the Red Hook outpost of Vane Brothers, a Baltimore company that operates a fleet of 12 tug boats and 20 barges in New York Harbor, worked to secure their vessels so they wouldn’t get tossed to sea. But managers realized at the last minute that they hadn’t considered the office building, situated at the south end of Court Street. The night of the storm, crew members handling Vane’s tug boats watched as water flowed into the company’s office. They’d put things up on desks, but “we had 38 to 40 inches of water in the building. The desks started floating and tipped over,” said Fleet Manager John Bowie.

Two large, rolling steel doors buckled under the weight of the water. Bowie returned the next morning to “an overwhelming sight, a really unbelievable sight.” While he could see the water line on the wall and only a few puddles on the floor, everything on the ground level was ruined or gone. The sea water had swept away equipment, furniture, computers, and paperwork. Some 20 vehicles were flooded, most of them totaled, Bowie said.

John Bowie, fleet manager of Vane Brothers maritime services in Red Hook

On the other side of the neighborhood is the 7,000-sq.-ft. industrial studio of Charles Flickinger, a world-renowned artisan, one of the few in the world who can bend glass for custom projects like the clock faces in Grand Central Terminal. His studio is situated on Pier 41, in a brick warehouse dating to the 1800s that juts elegantly into the New York Harbor. As Hurricane Sandy approached, Flickinger put sandbags up two feet high around his doors and boarded the windows. His wife grabbed computers on the way out. Everything else was sacked, he said. “It was a disaster,” Flickinger said. Drawers and machinery were filled and covered with water, oil, and raw sewage. The company lost $250,000 worth of equipment–custom gas ovens, automatic polishing equipment, motors. Fortunately, glassmaking molds from the 1830s, made of steel, survived the storm.

On Van Brunt Street, the neighborhood’s main drag, owners of the Red Hook Lobster Pound, which had launched in 2008 in the midst of the great recession, returned the morning after the storm to see dead lobsters floating in the muck. They lost nearly everything in the restaurant, as well as several delivery vehicles. Down the street, the husband-and-wife, carpenter-chef team of Ben Schneider and Sohui Kim, owners of the celebrated The Good Fork restaurant, returned to find the restaurant like a swimming pool. A 9′-by-9′, walk-in refrigerator was floating in the water, contents destroyed. Schneider rode on his freezer like a boat, he said, to go fetch a pump.

To Rebuild, or Give Up?

The prospect of cleaning up and rebuilding was daunting, even for Red Hook’s gritty, DIY types. Shane Welch, founder of Sixpoint Brewery, which suffered work-stopping damage to pumps and machines, said it was difficult even to get the repair process started. The city’s supply chain of parts and labor became heavily back-logged. “For a good couple of weeks, you had to wait 45 minutes to fill up your car with gas. The whole city turned into a Mad Max kind of thing. Red Hook in particular, because we were without power for a while,” Welch said. “Without power, you are totally screwed. You can’t do a lot of basic stuff.”

The cleanup “was a long, arduous slog,” glassmaker Flickinger said. “We lost a fair amount of business. Our customers had to go elsewhere. It was a great hardship for us.” His neighbor on Pier 41, Red Hook Winery founder Mark Snyder, said his winery was devastated and lost three vintages of wine. “I made an early commitment to recover. I didn’t want to disappoint my employees and all the small growers I had been working with since 2008,” he said in a Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce panel discussion this week on storm resilience for small business. But Snyder’s early estimate of the damage, $1 million, grew to $2.8 million. He said he had no flood insurance because he had been misled about what flood insurance actually covered, “so I didn’t get it.”

Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez, whose district includes Red Hook, spoke at this week’s panel about the critical early days of disaster relief for small business, perhaps analogous to the “golden hour” after a person suffers traumatic injury. “If you don’t get the assistance you need in the first three to four weeks, the probability of your business shutting down is very high,” said Velázquez, who serves as ranking member of the House Small Business Committee. In the case of disasters, loans from the SBA do not come fast enough, she said. “We are still dealing with a process that is really slow.”

Tone Balzano Johansen, owner of the iconic bar Sunny’s

“After every disaster, the first thing a small business needs is the capital to recover,” agreed Gregg Bishop, commissioner of city Small Business Services, who spoke on the panel. But in the case of Sandy, government agencies were swamped. “The problem with Sandy was that it was a disaster in multiple areas,” he said. At the same time, business owners seeking loans were often lacking the necessary documents, like income statements, because their computers had been ruined by saltwater. Even some companies with insurance, who had kept their policies up to date, were left hanging. “The insurance companies weren’t there for them, and I find that to be criminal,” Bishop said.

In Red Hook, volunteers came to the rescue of the business owners, who held fundraisers and launched online crowdfunding campaigns. “The extent to which people came to our aid was incredible and moving,” The Good Fork’s Schneider said, “both in physical labor, and financially. We all had to dig in and work ourselves to the bone to get on our feet. When I think of all the people who helped us, it was quite incredible.” Said the Red Hook Winery’s Snyder: “The most important lesson was to rely on community and myself and not wait for the federal government.”

In the storm’s immediate aftermath, PortSide NewYork, a waterway advocacy group and custodian of the historic 1938 tugboat Mary A. Whalen, set up an emergency center to aid small business, winning a Champions of Change award from the White House for the effort.

Lessons for the Next Time

Red Hook business owners say they’ll watch the weather more closely now, and do things a little differently, if another major hurricane is predicted. “We should have evacuated,” said Johansen, the Norwegian artist and owner of Sunny’s. “But the year before, with Irene, we all got stuck out in Jersey, and it was a pain getting back, and then it wasn’t as bad as they thought.”

Nearly everyone was unprepared for the wrath, but they’ve learned from the experience, and from neighbors. “It was acutely painful to me to see how hurt my beloved Red Hook was, when it didn’t have to be,” said Carolina Salguero, PortSide NewYork’s director. “As mariners, we understood the weather and we were preparing for four, five days,” she said. “Take the computer out of the cellar. Turn the power off in your building. Secure your fuel tank so it doesn’t float. Remove important documents,” she said. Move vehicles to higher ground. “That’s what we wish that people knew to do. And I hope they do now. Before you can get into preparations, you have to understand your vulnerability.” The Lobster Pound’s Povich said that in retrospect, she wishes she’d moved more inventory and her delivery vehicles. But as the storm approached, anxiety and panic got in the way, she said.

Povich outside her Red Hook flagship, which now has outposts in Manhattan and Montauk

Several owners said they learned that, to some extent, it’s futile to try to hold back the sea. “I’d probably leave the steel doors open a few feet,” said tugboat operator Bowie, to let water wash through without buckling the doors. “The water is going to come in anyway.” Flickinger, the glassmaker, agrees. “Our idea is to let the water wash in, and get it out as quickly as we can,” said the artisan. He’s got a storage room full of pumps, generators, and head lamps, should the need arise.

Some have made physical changes in their buildings to keep vital components above water. In the rebuild, Schneider rented a lot next door and installed a new walk-in fridge, up on stilts, but there are limits to changes he can make. “A lot of our operations are in the basement. There’s nowhere to move them,” Schneider said. If another big storm is predicted, Flickinger said, he’ll “jack up the machinery and put it on cinder blocks.”

At the Lobster Pound, an innovative “resilient power hub” will be installed on the roof by energy consulting firm Bright Power, thanks to a grant from RISE:NY, a city program to help small businesses become more resilient. At Sunny’s bar, Johansen’s back-up technology is modest: a crank-powered light with a USB port for charging a phone. “What am I doing to prepare for the next one? I’ve not hardly recovered from the last one. At least I have something,” she said, motioning toward her emergency light.

Facing the Rising Tide

Schneider says he’s not sure The Good Fork will remain in Red Hook if there’s another big flood. “We might decide to move to a different spot that’s safer,” Schneider said. In the meantime, however, he’s like most of the Red Hook entrepreneurs The Bridge interviewed: stoic and a bit fatalistic. “Fear, there’s not much a point of that. There are other things to worry about. We are lucky to have modern forecasting. We know when it’s coming.”

Make an aerial visit to Red Hook via our drone-powered tour of the neighborhood

“We will deal with the hand we’re dealt,” said Bowie, who has worked in the New York Harbor for 30 years. Said Povich: “That’s part of choosing to be in the flood zone. If you want to live on the water, this is the risk you take. And it’s a lovely place to be.” Povich owns her building, which made a difference last time. She says she might not have rebuilt if she were a renter.

“Red Hook is not like any other neighborhood,” Flickinger said. “Anyone who moved down here to do business is pretty scrappy. Everyone is doing things with their hands. Nobody is getting rich. You do what you can to prepare, and you try not to live in the wreckage of the future.”

Sixpoint’s Welch, for his part, has indeed been thinking about the future, given the “almost Biblical” nature of recent natural disasters. “New York is particularly vulnerable. There are a lot of low-lying areas. Red Hook is one of them,” Welch said. “Am I worried? Yes. But I’m not so worried about our business and Red Hook. I’m more worried about New York.” People tend to forget, he said, that Sandy had been downgraded to a tropical storm by the time it hit, and didn’t hit directly. “If it were a Category 4 hurricane that had a direct hit on Brooklyn or Manhattan, that would probably have wiped out the city. If New York got what Houston got, there would have been several million displaced people.”

“New York is the economic engine of the country,” Welch continued, advocating a big-scale approach to protecting New York from that kind of flood. “That would be crazy. That would be a natural disaster like we’ve never seen. I hope the leaders and local government are getting out in front of this.” We should perhaps look to the Dutch, he said, who “are crazy good at this. All the port cities have a series of canals and locks, so they can control storm surges and protect the city. New York is going to need something like that.”

Povich agreed about studying dikes and generally fortifying Red Hook, but is reconciled to the limits of what can be done. “The water is rising,” she said. “Come on, how can you stave off the ocean?”

Red Hook After Sandy: Flourishing But Vulnerable

With its 578 miles of shoreline, New York City is never far from the water, but few neighborhoods are more defined by their proximity to the blue than Red Hook. This isolated peninsula in southwestern Brooklyn sticks out into New York’s Upper Bay like a boxer’s chin, and water surrounds it on three sides, with the fourth walled off by the man-made river that is the Gowanus Expressway. During its late 19th century heyday, that location made Red Hook for a time the busiest freight port in the world and the center of New York’s lucrative cotton trade. When the maritime trade moved away from Red Hook after World War II, the neighborhood fell into steep decline, but today Red Hook is on the rise again, as first artists and now increasingly wealthy professionals have moved into the area, attracted by its independent spirit—and those water views.

But on Oct. 29, 2012, the water turned against Red Hook. The winds of Hurricane Sandy, striking at high tide, created a massive storm surge that pushed hundreds of millions of gallons of water onto and over New York’s shoreline. The resulting flood would cause $19 billion in damage throughout New York City, killing dozens of people, but Red Hook, which is so low-lying that nearly the entire community fell with the city’s mandatory evacuation zone, bore some of the worst of the storm’s wrath. As the Sandy-whipped water spilled over bulkheads along the shore, Van Brunt Street, Red Hook’s main thoroughfare, became a raging river, and nearly every other block in the neighborhood was inundated. Basements and cars were flooded out, and water even spat up from the sewers.

Part one of a three-part special report from The Bridge

The Fairway supermarket that sits inside a brick and wrought iron Civil War-era dock building was ruined, and wouldn’t reopen for nearly six months. The most lasting damage was done to the Red Hook Houses, a cluster of subsidized rentals where more than half of the neighborhood’s 11,000 residents live. The buildings lost access to power and clean water for weeks as the city’s Housing Authority struggled with the widespread damage, and were left ridden with mold by the floodwaters. “Red Hook was hit really hard,” says Jill Eisenhard, the executive director of the Red Hook Initiative, a community-focused nonprofit. “The storm was the disaster that we all feared.”

Yet five years later, virtually all visible signs of Sandy have vanished from Red Hook, and indeed much of New York. Homes and businesses have largely been repaired, and new residents, far from being scared off by the storm, are flocking in. New Red Hook buildings like the Basis Independent Brooklyn school have gone up in the years since Sandy, and pricey new condos are emerging on the neighborhood’s waterfront—so much so that in the third quarter of this year Red Hook became Brooklyn’s priciest neighborhood based on new-home sales.

In the aftermath of Sandy, Red Hook residents were served meals at the Red Hook Initiative community center (Photo by Radhika Chalasani/Redux)

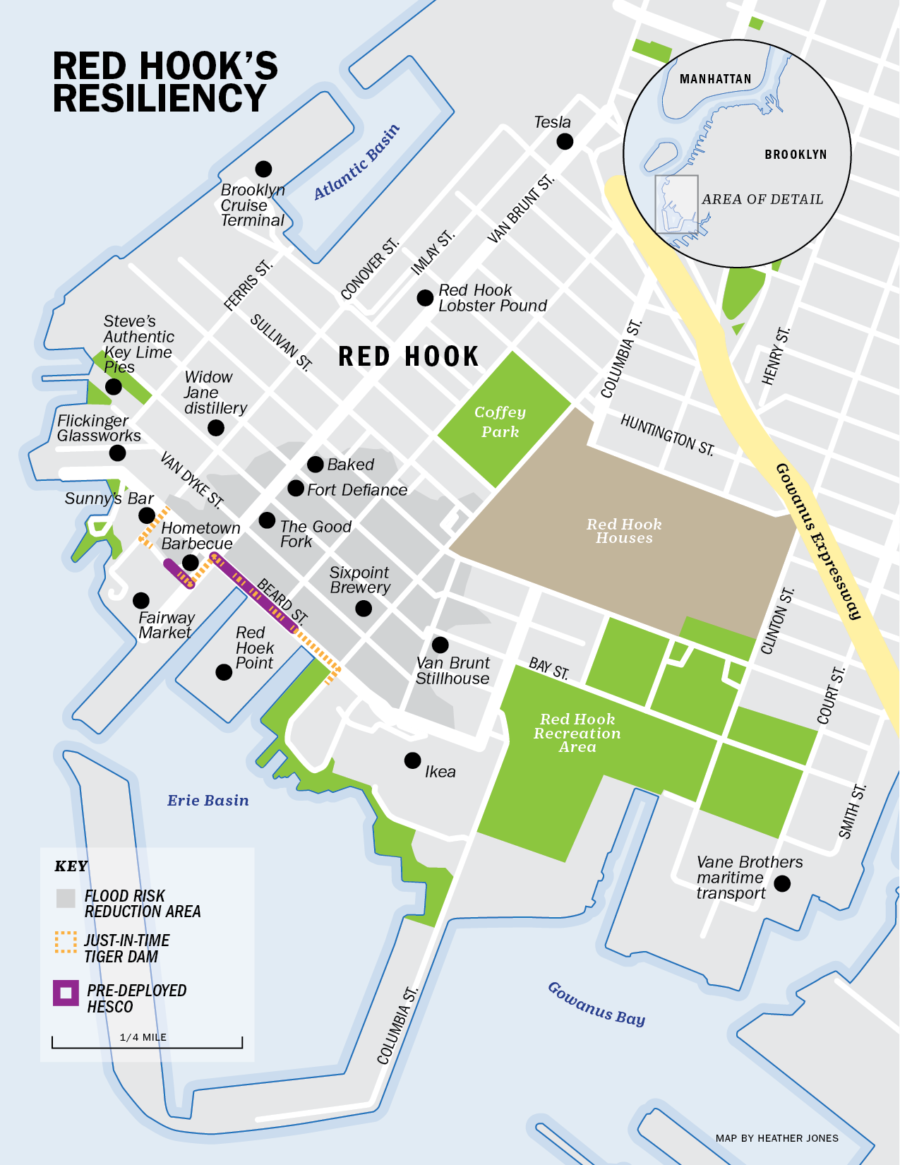

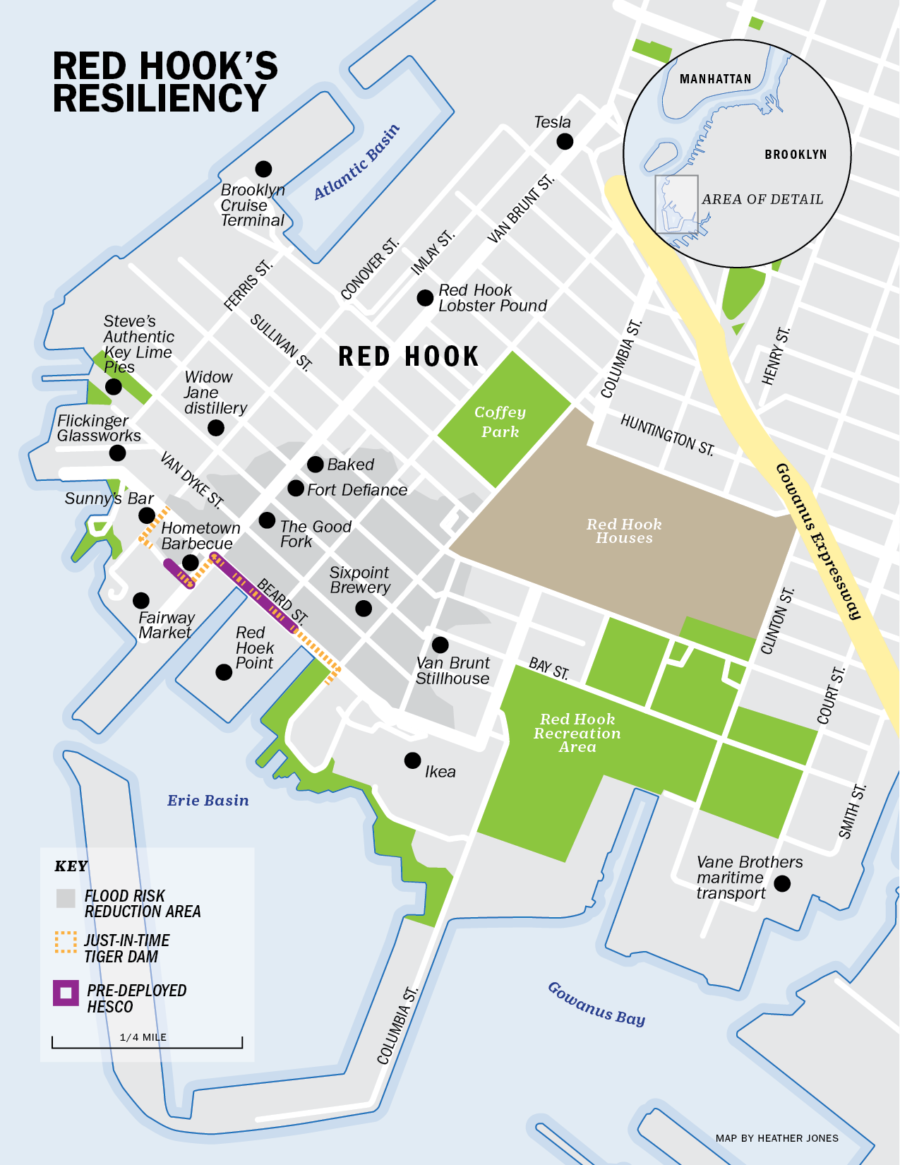

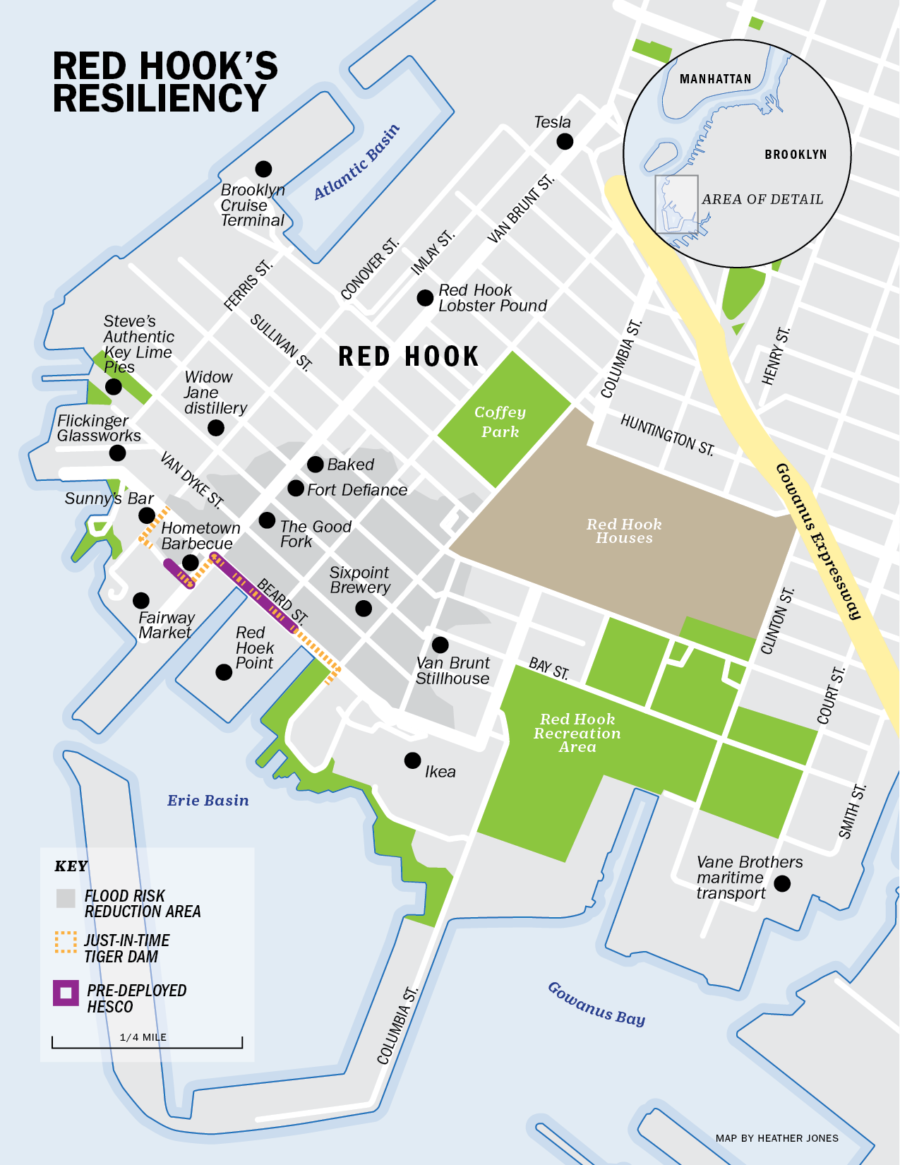

Defenses against the next storm are rising too. In Red Hook, that began with the installation of an interim flood barrier along Beard Street, and will grow to include a more permanent, $100 million Integrated Flood Protection System for the neighborhood. At the same time, Red Hook Houses are being repaired and renovated as part of the $3 billion the Federal Emergency Management Agency has allocated to New York to shore up the city’s housing projects, which were badly damaged by Sandy.

Altogether New York is allocating $20 billion on post-Sandy disaster recovery and resilience, enough to put the city at the forefront of national efforts to get ahead of the impacts of storms, floods, and climate-change-related sea-level rise. “We’re certainly better prepared now for the next storm in a number of ways,” says Robert Freudenberg, vice president of energy and environmental issues at the Regional Plan Association, a think tank that focuses on the metropolitan area. “New York has laid out a clear blueprint of what needs to be done to protect from future storms, and that’s far ahead of other places in the country.”

Make an aerial visit to Red Hook via our drone-powered tour of the neighborhood

But being ahead of the rest of the U.S. doesn’t mean New York is safe from the next Sandy. That temporary flood barrier in Red Hook? It’s designed to protect the neighborhood against relatively minor storm surges, not the sort of historic blow Red Hook suffered during Sandy—and the barrier itself has been downsized from the $200 million system the neighborhood was promised after the storm. For all New York is doing, the city isn’t keeping up with the larger and long-term threat of sea level rise—and by supporting continued development along the waterfront, including in Sandy-hit neighborhoods like Red Hook, New York is actually accentuating the risk that will come with ever-worsening floods.

The truth is that with the seas around New York pegged to rise by several feet by the end of the century, there may be no truly long-term future for waterfront neighborhoods like Red Hook—at least, no future that resembles the present. “The only answer is going to be to plan for the inevitable on sea-level rise, and that could mean retreat from the shoreline,” says Nicolas Coch, a coastal geology expert at Queens College in New York. “But no one wants to think about that.”

Red Hook Under the Surface

Even though the shape of Red Hook’s waterfront really does look like it could be found at the end of a fishing line, the “hook” in Red Hook is actually “hoek”—a Dutch word from the neighborhood’s founding that means “corner.” (The “red” in the name came from the reddish color of the area’s clay soil.) If you walk to the intersection of Dikeman and Ferris streets, you’ll be standing near the original Red Hook. At the time of the community’s founding in 1636, the point was on an island that stuck out into New York Bay, and much of what is Red Hook today was marshy land broken up by tidal ponds. The fully formed neighborhood today is mostly man-made, composed of landfill—garbage, really—that seized space from the surrounding waters.

As a result, Red Hook is not just flat and low-lying but shallow and porous—the groundwater table sits only 5 to 10 feet below the surface, which is why some of the flooding during Sandy came up from under the ground, like a swimming pool that had been overfilled. When Sandy struck, the water was really just taking back lost territory, as it did in the most heavily-flooded areas of lower Manhattan—also built on landfill. Red Hook will always be vulnerable to flooding, and it will always be a challenge to defend.

National Guard members delivered supplies at the Red Hook Houses, which had no power or water for weeks after the storm (Photo by Kirsten Luce/The New York Times/Redux)

For most of Red Hook and New York’s existence, however, flood risk wasn’t on anyone’s mind. The city’s decades of rapid growth through the 19th and 20th centuries happened to overlap with a period of meteorological quiet. In 1821, a hurricane hit New York City squarely, producing what is now estimated to be 10- to 11-ft storm surges. (The storm surge at the Battery in lower Manhattan during Sandy reached a record-high 14.06 ft.) But in the early 19th century, New York’s population was little more than 100,000 people, and the tidal ponds that filled Red Hook at the time would have absorbed much of the flooding.

After the 1821 hurricane, New York wouldn’t experience a storm of similar magnitude until Hurricane Donna in 1960, and even the decades that followed were calm until Sandy. That was a lot of time for New York to grow into one of the biggest cities in the world, all without having to worry about storm surges. “New York has been thumbing its nose at the sea for hundreds of years now,” says Ted Steinberg, a professor at Case Western Reserve University and the author of the book Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. “Leaders should have known that the city was uniquely vulnerable to flooding because of its location. Sandy was a wake-up call.”

Preparing for the Next One

To their credit, New York’s leaders have mostly answered that call. Even before the storm, then-Mayor Bloomberg had convened the city’s own panel on climate change, which presciently warned that global warming and sea-level rise were raising the likelihood that New York would be hit by a major flooding event. After the storm, the city released a 438-report that outlined the city’s plans for resiliency, including 257 separate projects, and Mayor de Blasio has kept those plans going. The MTA will be spending billions to fix the New York’s extensive subway system, much of which was flooded by Sandy, and to fortify public transit against the next storm, installing thousands of rapid-deployment covers to ensure the underground system stays watertight next time.

A line of four-foot Hesco barriers has been installed along Beard Street to protect against storm surge (Photo by Steve Koepp)

New York’s Housing Authority, which oversees the city’s 2,600 public-housing buildings, will be spending $3 billion from the federal government to repair the catastrophic damage suffered during the storm. (A fair number of New York’s public housing projects—including the Red Hook Houses—sit near the water, and many of the buildings were in a state of disrepair well before Sandy struck.) “I think you can say the city is on the right track,” says Henk Ovink, a Dutch architect and the former senior advisor for President Obama’s Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force. “And you can also see we need to pick up our game.”

Ovink was the driving force behind Rebuild By Design, the most ambitious of New York’s post-Sandy recovery projects. Launched by Obama’s Housing Department and the Rockefeller Foundation and other organizations, Rebuild By Design invited architects and designers to dream up the most innovative—and green—ways to create a more resilient New York. And it made financial sense—while the winning efforts for Rebuild By Design were funded with a total of $930 million, studies have shown that each dollar spent on disaster mitigation saves $4 on post-disaster spending.

But as the years have passed and memories of Sandy have receded, some of the momentum around the most ambitious efforts has been lost. Take the biggest project to come out of Sandy: the Big U, conceived as 10 continuous miles of flood protection wrapping around the shoreline of lower Manhattan. Instead of a single wall against floods, the Big U would incorporate greenery and parks. “[They] can capture stormwater runoff,” says Ovink—and indeed, when much of the coastline around Manhattan and Brooklyn was still wetlands and tidal ponds, that’s exactly what happened.

Those days are long gone. Streets and buildings now run up to the water’s edge, often on land that used to belong to the water. And while the Big U would provide a welcome return to a softer and more resilient coastline, ground has yet to be broken on the project. (The city has said that it expects to start construction by late 2018 to early 2019.) Indeed, virtually none of the most ambitious flood-protection projects that were considered in the immediate aftermath of Sandy—including a massive sea barrier spanning New York Harbor south of the city—seem likely to happen any time soon. The Big U could come in at some $3 billion, while that larger flood barrier would cost billions more.

Red Hook has experienced that shrinking of ambition on a smaller scale. Running down the water-facing Beard Street from the Fairway Market to the vast Ikea megastore, as well as on a stretch of Reed Street, is part of Red Hook’s Interim Flood Protection Measures. The four-foot-tall Hesco barriers are made of blocks filled with sand—openings in the wall, which are needed to allow passage on driveways, can be blocked with inflatable barriers in the days before a storm. The Red Hook system represents the first neighborhood-level use of the Hesco barriers, and it is meant to be a first step. the more permanent plans for the Integrated Flood Protection System include raising Beard Street and building a flood wall underneath it, as well as putting a second flood wall in nearby Atlantic Basin.

But those more permanent projects are dependent on federal funding that seems somewhat less likely with President Trump in office. (Just days before Hurricane Harvey inundated Texas, Trump revoked Obama-era rules that would have required the federal government to take into account the risk of flooding and sea-level rise when constructing new infrastructure or rebuilding after disasters.) “It’s great that this system is in place, but it’s only going to cover a small portion of the neighborhood,” says Russell Unger, the executive director of the Urban Green Council, a non-profit that works on sustainable building.

The city has said that Red Hook’s measures will protect against a 10-year flood—meaning a flood that has one-in-10 chance of happening in any given year. Sandy was worse than a 100-year flood—studies after the storm showed that the flooding was significantly worse than what the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), charged with maintaining flood maps, had expected for a 100-year flood. “If it was a Sandy-level storm, [the barrier] would not protect it,” Jessica Colon, a senior policy advisor for the Mayor’s Office of Recovery & Resiliency, told the audience at a public presentation in Red Hook in June.

That would be worrying enough if Sandy were the worst New York could ever expect. But it’s not. Thanks to climate change, Sandy will just be the start.

Red Hook is beloved for its waterfront and reminders of its industrial past, including this street car near the Fairway supermarket (Photo by Timothy Fadek)

The Long-term Rising Tide

Sandy would have been a catastrophic storm even without the effects of climate change. But the waters around New York had already risen by about a foot over the past century, which added to the storm surge, just as raising the floor of a basketball court would make it easier to reach the basket. And in the decades to come the seas will keep rising—as soon as the 2050s, upper estimates suggest that sea-level rise could reach two and a half feet. (As if climate change isn’t bad enough, the land in New York is actually sinking, accentuating the effects of sea level rise.) The New York City Panel on Climate Change estimates that a 100-year storm under that amount of sea level rise could result could result in 72 square miles being flooded—nearly a quarter of the city. “With sea-level rise, a given hurricane is going to cause worse damage,” says David Titley, the director of the Center for Solutions to Weather and Climate Risk at Pennsylvania State University and a former rear admiral in the U.S. Navy. “What we had called the 100-year or 500-year floodplain simply isn’t anymore. These waters are coming in.”

They will be coming in more often, too. In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Oct. 23, Professor Andra Garner, Benjamin Horton and their colleagues looked at the latest science on the impact of climate change on New York coastal flooding risks. They found that, thanks mostly to sea level rise, the frequency of near Sandy-level floods would change from approximately every 25 years now to as often as every five years between 2030 and 2045. That’s soon—you could buy a condo with a water view in Red Hook, and you might be experiencing that level of flooding before your 30-year mortgage is paid off.

And it’s not because stronger hurricanes will hit more often—the researchers actually found that any expected increase in tropical-storm power will likely be offset in the future by shifting weather patterns that steer hurricanes away from New York. It’s because the seas will rise even faster than we expect, leaving New York—at least as it is now—at near-perpetual risk of devastating floods, like a bathtub filled to the brim. “These results are quite shocking for New York,” says Horton.

Climate Central, a Princeton-based nonprofit that analyzes climate science, has created interactive maps that try to predict how coastal cities will ultimately be affected by the sea level rise that will be caused by different rates of warming. Under a scenario with 2 degrees C (3.6 F) warming—which is the increasingly difficult to achieve goal of the Paris Climate Agreement—Red Hook is eventually submerged, as is nearby Gowanus. (You don’t want to know what the 4 degrees C (7.2 F) maps look like.) While it’s difficult to predict exactly how long it will take a set amount of global warming to increase sea levels this much, it will happen—and the latest science suggests it will happen sooner than we long thought. Without significant and costly defenses, the waters will ultimately retake Red Hook and many other shoreline New York neighborhoods.

With most of the neighborhood only a few feet above sea level, Red Hook is vulnerable to the rising ocean (Photo by Lucas McGowen, via drone)

Professor Klaus Jacob, a geophysicist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has long warned of way rising seas would reshape and destroy New York City. In 2008 he produced a prescient report for the MTA warning that many of its lines would flood with a storm surge between 7 and 13 feet. Jacob’s report encouraged the agency to take steps that ultimately helped mitigate some of the worst effects of Sandy. But he is deeply pessimistic about New York’s long-term future in a warming climate—and deeply frustrated that despite the evidence left by Sandy, the city continues to put new developments in vulnerable shoreline areas, including Red Hook.

At a 2016 speech to the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, Jacob showed slides of a proposed development along the Red Hook waterfront would be accessible only by ferry by 2100, because the rest of the neighborhood would be underwater. “We have already problems in the current sea level,” Jacob said in his talk. “We know that sea level rise will amplify those risks. We can go about it by protection, and that’s largely what we’re doing, but I think it’s not sustainable in the long run. We can do accommodation again, but it’s an interim [solution] … And we have strategic relocation. And I suggest that this is the only truly sustainable solution.”

A Commitment to the Waterfront

In the aftermath of Sandy, Mayor Bloomberg made it clear that, whatever the city would do to strengthen its defense, it would not pull back from the water. “We cannot and will not abandon our waterfront,” he said. “It’s one of our greatest assets. We must protect it, not retreat from it.” And that, ultimately, is what the city has tried to do, in fits and starts, in the five years since Sandy. So has the construction sector—many of the new condos and other developments being built along New York’s waterfront, including in Red Hook, will have their own protections against rising seas and floods. “We’re living in a world in which technology has changed how construction can happen,” says Carlo Scissura, the president of the New York Building Congress. “We can do things the right way.”

The city has a powerful incentive to keep building along the waterfront: population. New York already suffers from an affordable-housing crisis, and one of the only solutions is to build more housing in neighborhoods like Red Hook where vacant or underused industrial space—often along the water—can be converted to residences. Yet to do so is to put more people in the path of the next Sandy—or to lock New York into spending unimaginable amounts of money on massive flood protections just to keep the city dry.

That is the essential urban quandary of the 21st century, as city leaders are left to adapt to a climate threat that, as Horton notes, “the globe could have solved for far less 20 years ago.” With Trump in the White House, that’s even less likely—the U.S. has already announced it will withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change, and this month EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt moved to repeal former President Obama’s greenhouse gas emission regulations. “From the greater focus of reducing emissions, we’re moving more and more to adaptation, and thinking about how cities can be effective at the local level,” says Armando Carbonell, the head of urban planning at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Fortifying the Neighborhood

The good news for vulnerable neighborhoods like Red Hook is that there is still much that can be done in the near term—and that adapting to sea-level rise and climate change involves more than hard sea walls. Existing buildings, even decades-old brownstones, can be renovated in ways that make them less vulnerable to frequent floods, by moving boilers and electrical equipment above flood levels. (New or “substantially renovated” buildings are required by law to make these changes.) The IKEA superstore in Red Hook was able to weather Sandy thanks to a design that elevated vital equipment and merchandise. The floodwaters mostly washed through IKEA’s ground-level parking lot, while an on-site generator enabled the store to reopen just a couple of days after Sandy hit. While other businesses in Red Hook were knocked out by the storm for weeks or even longer, IKEA became a nerve center for the neighborhood’s recovery.

To help people who lacked heat, volunteers brought blankets and other supplies to the neighborhood (Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein)

And that recovery was driven by the same independent spirit that has characterized Red Hook from its birth. Volunteers from groups like the Red Hook Initiative and neighbors from down the street came together to provide hot meals, information, and even access to generators for residents—especially at the Red Hook Houses—who needed help. That included work to deliver supplies directly to the many in the neighborhood who were housebound. (Homes in Red Hook may be selling for millions of dollars, but the neighborhood as a whole has a 45% poverty rate.)

In the years after the storm, a coalition of neighborhood nonprofits put together the Ready Red Hook program, a disaster preparedness plan that focuses on helping the community in the first 72 hours after a catastrophe, the vital window before additional assistance from the city or federal government is likely to arrive. That made Red Hook the first New York neighborhood to complete its own community recovery and disaster response plan. “This may not sound like a climate-mitigation effort, but it makes a difference to work with the community on efforts like this,” says Ronald Shiffman, a veteran city planner and a professor at the Pratt Institute.

Here’s a hard truth: no one really knows how to adapt to the coming climate-related floods. So much of urban planning, or any kind of planning, is built on the past. But as climate change accelerates, the past no longer provides an accurate map to the future—even a past event as recent as Sandy. “The solutions of the past won’t protect us from the future,” warns Ovink. To survive a wetter and warmer tomorrow, neighborhoods like Red Hook will need to be creative and flexible, and they’ll need help from the city and the federal government. But most of all, they’ll need to depend on themselves.