Made in Brooklyn, Right in Front of Your Eyes

How a new brand with vision, Lowercase, created a stylish product rarely manufactured in America anymore: eyeglasses

Lowercase's products are painstakingly crafted in the Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park (All photos courtesy of Lowercase)

You think you know something.

Take a simple pair of glasses. Perhaps you’ve been wearing them since kindergarten (not the same pair, of course). They might seem like an expensive and necessary accessory, maybe even a nuisance.

But it turns out there’s so much more that goes on right under (or over) your nose.

The manufacturing process involves at least 30 steps

Glasses can communicate a sense of style, or even reflect a sense of place. And now, with the launch of Brooklyn-based manufacturer Lowercase, a pair of glasses can tell a story about your own borough.

That wasn’t what Gerard Masci had in mind when he had the somewhat wild idea to bring eyeglass manufacturing back to the U.S., but that is part of the outcome. Out of a small space in the hulking Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park, Masci and his business partner Brian Vallario are doing something both a little bit crazy and yet very appropriate for the borough: They’re making glasses.

If you dream up an image of the cliche Brooklyn hipster, the go-to accessories would be a precisely groomed mustache, full tattoo sleeve, and a thick set of plastic specs.

Look a little closer though and the truth would reveal itself: those specs were made in China. Or Italy. Or Japan. The eyewear manufacturing industry is almost entirely controlled by French frame company Luxottica, which in January merged with lens maker Essilor International, creating a glasses Goliath with a market value of nearly $50 billion. Oakley and Ray-Bans were once made exclusively in the U.S., but after both companies were bought by Luxottica, they outsourced their manufacturing to China, Italy, and elsewhere. And what of Luxottica’s stylish online competitor, the popularly priced brand Warby Parker? Also made in China.

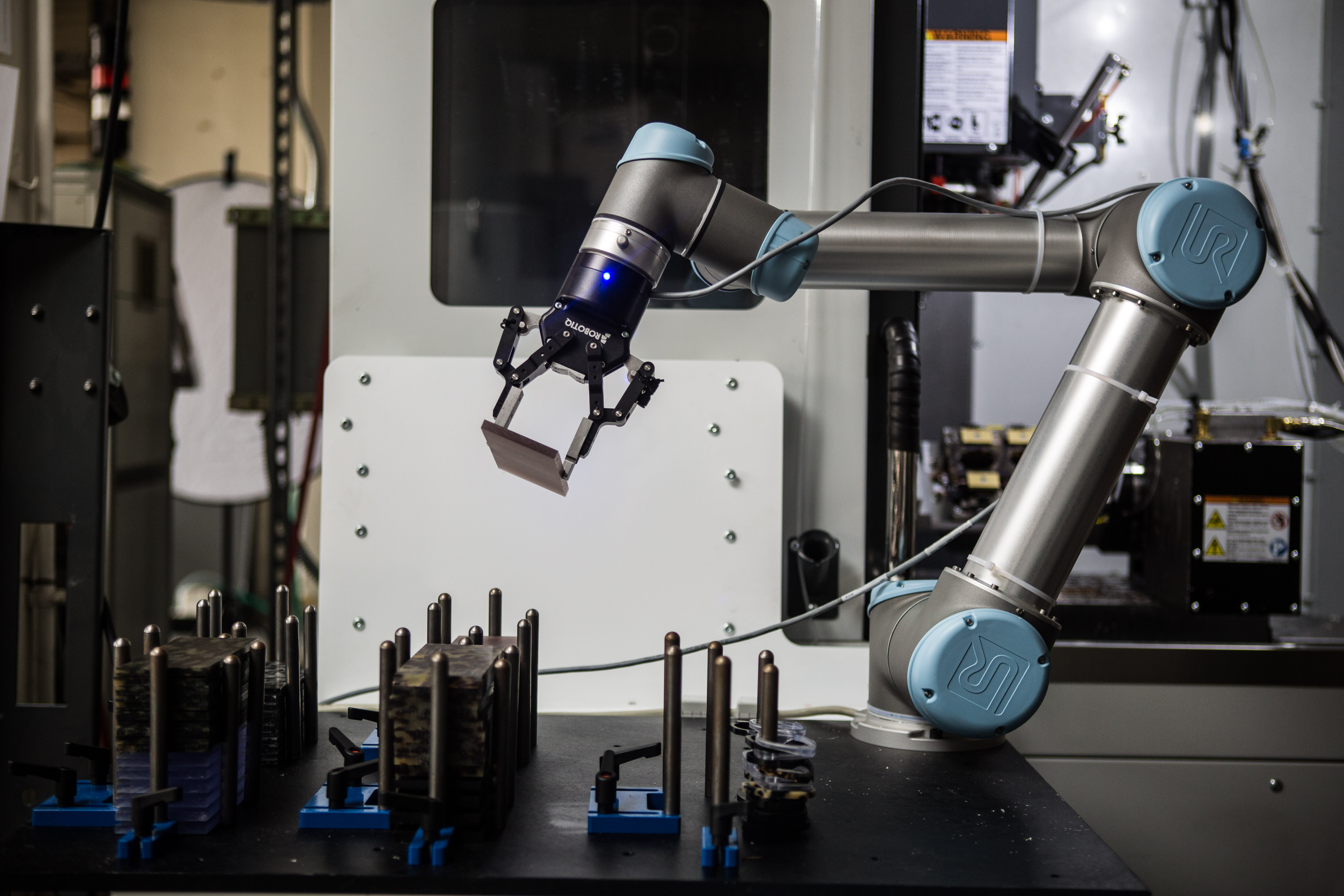

A robotic arm moves the raw material: small sheets of acetate

So there wasn’t much someone who wanted to buy locally could do about her fancy frames. Until now. After its low-key January launch, Lowercase is open for business with a core collection of 10 styles of glasses and sunglasses selling for $300 apiece, all made by a couple of guys and some very big machines from Italy down on 58th Street.

After a tour of their manufacturing process, it’s hard to overemphasize how impressive it is to create frames in a small-batch production process. Seeing them up-close will make you hyper-aware of every hinge, pantoscopic tilt, or crookedness of your own favorite pair.

After a career in finance, Masci was ready for something completely different

Starting from Scratch

Eyeglass manufacturing doesn’t seem like the kind of practice a person might stumble into, but that’s exactly how Gerard Masci found himself counting the number of wood chips necessary to tumble frames to a high-gloss finish.

It wasn’t a straight road to entrepreneurship. After college, he worked in finance for 11 years, clocking time at Goldman Sachs and hedge funds, eventually working as a research analyst at Soros Fund Management. All was going well until 2012, when Masci was struck with a mysterious, debilitating illness. “I was practically comatose for two years,” he says. His wife will recall situations or conversations now that he has no memory of. He was unable to work or go about his normal routines, until one day a doctor finally came up with a new diagnosis, the first of many fortuitous occurrences. At this point in telling the story, Masci snaps his fingers: “Like that, I was better,” preferring not to labor the details of his recuperation. But his old job was gone (though he says they were understanding about his health situation) and he had to rebuild his life. He began considering different avenues and asked himself, What did he actually like?

The answer was right in front of his face.

Masci had amassed a collection of frames over the years and thought, well, he could do something with glasses. This despite no manufacturing background, no design experience, no awareness of how intimidating it might be to go up against the eyewear behemoth Luxottica. He just knew what he liked and had nothing to lose.

Vallario had a background in manufacturing, architecture and design

So he started to learn.

First, he went where anyone should go when they want to acquire a new skill: YouTube. Masci watched videos of eyewear production, gleaning hints of the manufacturing process. He tried to build relationships with suppliers in Italy and China, despite speaking neither language. He was a “nobody,” as Masci cheerily admits now. There was little incentive for huge suppliers to work with a one-man operation: “It’s like going to Exxon and saying you want a bucket of oil.”

He remained at a crossroads for six months before cold emailing an address on the website of acetate producer Mazzucchelli 1849. Turns out the prestigious Italian brand had an office in Greenwich Village, one block from where Masci grew up. Another fortuitous sign. It was there he met Megan Cooper, who told him other people had wanted to bring production back to the U.S., but virtually no one had actually followed through. She championed his idea and helped him navigate the byzantine process of finding suppliers. Now a pair of glasses is named Cooper in her honor.

Meeting of the Makers

Yet it wasn’t until June 2015 that this germ of an idea went, in the words of Masci, from “research project-slash-business school case study to, Oh, we’re starting a business.” Masci was looking for someone to operate machinery, and a friend recommended he talk to Brian Vallario, who worked as a designer at the architectural firm SITU Studio and might know someone.

The newly made frames are tumbled with wood chips to give the parts a lustrous shine

They met at the Marlton Hotel in Greenwich Village, where Vallario once lived while studying at Parsons, and after hearing Masci’s pitch about creating an eyewear company from the ground up, Vallario didn’t have a recommendation: he wanted in. (They’ve since named a frame Marlton.)

Vallario’s background in manufacturing, architecture, and design proved a perfect fit. Vallario was burnt out on creating high-end residential properties. Now he’s laser focused on the tiniest details. “The way design comes out best is when you’re really intimate with the process,” he says. While the partners worked with a designer on the shapes, colors, and fit of their first collection, they’re planning the next collection on their own.

Buffing is one of the final steps in the process

Finding the Manufacturing Space

Locating a place that could house their manufacturing was another story altogether. They needed solid floors for their very expensive machinery. Many commercial landlords didn’t want to house a company that was actually manufacturing products—ironic, given the amount of love for “Made in Brooklyn” products—and others with ground-floor spaces were charging up to $40,000 per month.

After months of searching, Lowercase found their home in the Brooklyn Army Terminal. Typically companies there take up 20,000 sq. ft.; Lowercase has just over 2,000. Their current rent in the city-owned property is only $3,700 a month.

The BAT itself is grand and imposing. Built in 1919 as a military depot and supply base, the 4 million sq. ft. space is now a manufacturing hub that few Brooklyn residents have even ventured near. But they should. Upon walking in, a photo of Elvis welcomes you. The King—along with 3.2 million other U.S. soldiers during WWII—was shipped out to Germany in 1958 straight from this giant mass of concrete.

Now the terminal is home to companies ranging from chocolatier Jacques Torres to gift retailer Uncommon Goods. Along one quiet corridor, a Lowercase name plaque made of acetate signals you’ve arrived at their design and manufacturing studio, and upon walking in you might expect to see an assembly line of workers. Nope. There’s just Gerard, Brian, and Ryan Langer, a former coworker of Vallario’s who joined after the launch to help with manufacturing.

They’re a lean team for a reason; Masci was insistent about not taking on outside investors before the launch. “We wanted control over quality and process,” he says, and didn’t want to deal with rushed production or ushering out a subpar product. So he’s bootstrapping the entire farsighted operation. For now though, Masci and his crew are more than happy with where they find themselves, five flights above the ground floor.

Lowercase offers a core collection of 10 styles of glasses and sunglasses selling for $300 apiece

The Painstaking Process

Glasses might appear simple, utilitarian, but they’re surprisingly complex. Masci claims there are 30 steps to making every pair. He’s lowballing to sound modest. There are many more, which also provide plenty of opportunities for something to go wrong.

Making a pair starts with long, rectangular sheets of acetate sourced from Italy. Unlike other oil-based plastics, acetate is primarily made from wood pulp. This makes it extremely durable, but also susceptible to water or heat, a point made clear to anyone who’s left sunglasses on the beach only to have them warp under the sun’s rays.

After the sheets are cut down to size, they’re placed in an oven to dry out; next, they’re narrowed down on an adorable, Italian pastel-green planer that had better be pleasing to the eye: it cost €20,000. These smaller acetate pieces go into the $75,000 computer-controlled cutting machine, which is where the magic happens. From a boring rectangle comes a stylish, flat frame.

One of the most fickle operations involves the core wire shooter, which is nearly as violently awesome as it sounds. The machine heats up a single temple, then shoots the wire into the hot acetate, which is then immediately cooled. (The role of the wire is to keep the temple straight.) If anything is slightly off—temperature, timing, sizing—bubbles form, the wire bends, and the temple gets trashed.

Next is the most secretive part of the process: the tumbling phase. Acetate can have a dull film and rough edges after machining, so frames become showroom-worthy by getting thrown into giant vats full of wood chips and paste. They’re tumbled and cleaned for days until they’re gleaming.

Gleaming, but not finished, of course. (Told you the process was intense.) Frames are then heated and manipulated to achieve the pantoscopic tilt, the degree to which glasses are angled on a wearer’s face. Hinges pieces are inserted into the frame fronts with the help of a sonotrode, or ultrasonic horn.

Lowercase’s sunglasses offer an edgier, retro look

Not to say there aren’t hitches. When a piece of machinery breaks, there is no local supplier. The part must travel from Italy. And smaller details can go awry, too. Masci notes that they were riding high after special-ordering 2,000 glasses cases—but once they arrived, none of them were the right size.

‘The Best Thing I’ve Ever Done’

Now that their collection is available online and through optical shops in the Northeast, they plan to release capsule collections every year, with certain frames and colors available exclusively on the website. After the long process from idea to execution, Vallario says a recent friends-and-family sale was especially gratifying: “They’ve watched us go through this for 18 months.”

This entire endeavor was driven by Masci’s single-minded focus based not on trend reports, but his own personal interests. Despite one or two bumps in the road, “It’s still the best thing I’ve ever done in my life,” says Masci, a man clearly in love with the process. “If it fails tomorrow, sure, I’d be sad, but I couldn’t have enjoyed anything more if I had all the money back.”

“I got kicked out of comfort,” he says. “If I was still working at Soros…” Masci pauses. “Where I was, there was no risk. Inertia is a powerful force. As my wife says, ‘You getting sick was the best thing that could have happened to you.’”

Before leaving Lowercase’s studio, I finally tried on a pair of glasses. They felt strong and sturdy, and though I wasn’t near a mirror I felt like they made a statement. I guess you could say they felt like they were made in Brooklyn.