How Fixing an Overstressed Region Could Change Brooklyn

The tri-state area needs big investments and better leadership, a planning group warns. We highlight 16 ideas, from possible to pipe-dream, that could remake the borough

A rendering of new rail links traversing the Brownsville neighborhood (All images courtesy of the Regional Planning Association)

Even as New York City has flourished in recent years, its physical flaws have become painfully apparent: broken-down subways, unaffordable housing and vulnerability to climate change, among other ills. All of these hit home particularly hard in Brooklyn, the most populous borough. Can they be fixed?

It’s easy to dismiss such problems as too big to tackle. But one group, the Regional Plan Association (RPA), considers those challenges its reason for being. The venerable research group, funded by businesses and foundations, is known for thinking big not just about the city but more broadly the tri-state area. Its first regional plan, issued in 1929, laid the groundwork for highways and parks; its second plan, in the 1960s, promoted regional economic development; and its third plan, in 1996, pushed transit investments like the Second Avenue Subway and envisioned developing Manhattan’s Far West Side.

Now comes The Fourth Regional Plan: Making the Region Work for All of Us, which offers many ambitious proposals, some pie-in-the-sky, others eminently practical. The rationale for pursuing them is eye-opening, for it paints the picture of a city and a region constrained by unwise decisions and unprepared for future growth. Lack of investment in housing and infrastructure could make widening inequities even worse. According to the RPA plan, “The region gained 1.8 million jobs over the past 25 years, but is likely to grow by only half that number over the next quarter century” unless major changes are made.

When the plan emerged Nov. 30, the headlines mainly concerned the controversial proposal to shut down subway service overnight on weekdays to hasten repairs (while adding buses) and for a new entity, a Subway Reconstruction Public Benefit Corp., to revamp the system within a brisk 15 years. That focus was understandable; no institution is as central to daily life as the subway.

But the 376-page study–which contains 61 proposals for improving the city’s institutions, transportation, climate-change resiliency, and affordability—could mean far more. It suggests new residential and travel patterns, new business opportunities and workforce development. Most notably, it recommends much-expanded infrastructure, including subway extensions, express buses, and affordable broadband.

Looking out to 2040

It won’t be simple to deliver what the RPA calls “greater equity, shared prosperity, better health, and sustainability.” Big budgets and political leadership–if not consensus–are required but elusive in many cases, notably in the fraught relationship between our governor and mayor, and a federal government wary of providing financial aid.

As New York magazine columnist Justin Davidson put it, the plan “seems perfectly timed to address increasingly urgent problems but appallingly out of sync with today’s political climate.” Newsday, calling it a “conversation-starter, not a blueprint,” opined that, “by going really broad, the RPA made it too easy for more practical, doable suggestions to get lost in splashy, easily dismissed proposals.”

Yet it’s worth keeping the Fourth Regional Plan on your radar screen, since it provides an epic to-do list for making a better city, especially in its outer boroughs. (After all, who knew a decade ago that something like Brooklyn Bridge Park could get built?) We highlight certain issues relevant to Brooklyn below, and offer some speculation on their future.

1. Fix the subways, and do it faster

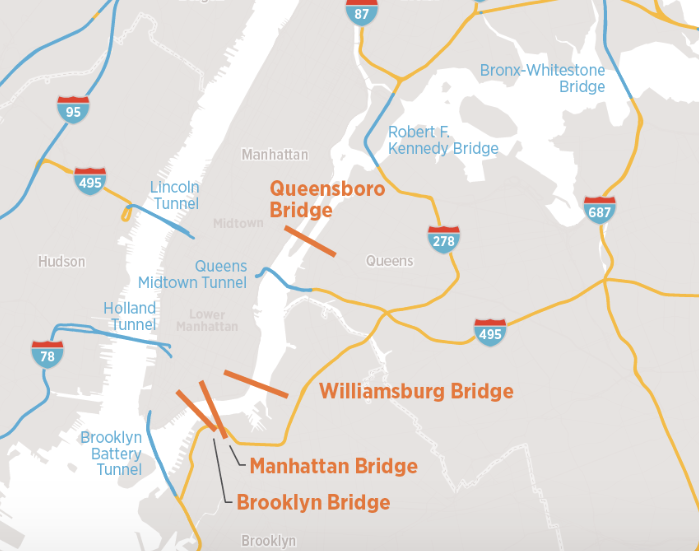

The report recommends congestion pricing to reduce traffic and finance mass transit

The recommendation for a new subway manager could “end the continuous cycle of runaway construction costs,” the RPA says. (Other major cities, the RPA has said, do far more with less money.) Still, a revamp requires money. The RPA recommends congestion pricing: tolls on all crossings into Manhattan south of 60th Street, which would reduce “toll shopping” which now clogs the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and neighborhood streets near the free bridges.

The RPA also recommends tolls to reduce traffic on regional highways and that drivers be charged for miles, via a Vehicle-Miles Traveled (VMT) fee or Miles-Based User Fee (MBUF) that uses GPS and cellular technology. Fees could vary based on capacity, vehicle weight, or fuel efficiency.

Outlook: Though the MTA, Mayor de Blasio and the Daily News slammed the overnight shutdown idea, the New York Times and Crain’s New York Business weren’t opposed. The Daily News endorsed the new entity; New York Post columnist Nicole Gelinas suggested caution. The New York Times’s devastating dissection of subway-cost overruns gives momentum for change.

Congestion pricing has been a heavy lift since Mayor Bloomberg proposed it, but Governor Cuomo—though not de Blasio—has embraced the MOVE NY plan. Adding tolls and fees more regionally “could provoke heated debate,” as Newsday noted, and would have to come later, requiring a new regional organizing body, as well as privacy safeguards.

2. Extend subway lines

The plan proposes two subway-line extensions for Brooklyn

Neighborhoods like East Flatbush, Flatlands, Marine Park, Mill Basin and Sheepshead Bay deserve more transit service, the RPA says, among underserved locations in the city. It recommends extending the No. 4 subway four miles under Utica Avenue from Eastern Parkway to Flatbush Avenue. (The city has funded an MTA study of this possibility, but it’s been delayed.)

The RPA also recommends that the No. 2 and No. 5 lines be extended 2.7 miles under Nostrand Avenue from Flatbush Avenue to Avenue Z. Another, almost glancing suggestion is to extend the No. 1 line from South Ferry under the East River to Red Hook if it “continue[s] to develop.”

Outlook: The Utica Avenue plan, transit blogger Ben Kabak wrote last February, needs a champion, but doesn’t have one. The same is true for Nostrand Avenue, as of now. Regarding Red Hook, the ambitious and controversial plan the engineering firm Aecom floated in September 2016 to build 45,000 apartments, surely depends on the subway extension rather than vice versa.

Some suggest caution. As journalist and Brooklyn state-Senate candidate Ross Barkan tweeted, rather than build new subways, “For far less money, we could redraw bus routes, speed up commute times, and have a world-class on-the-ground transit system.” The MTA, queried by the Times about new subway lines, declined comment. New construction seems plausible only after repairs are accomplished swiftly and within budget.

3. Create a new Triboro rail line

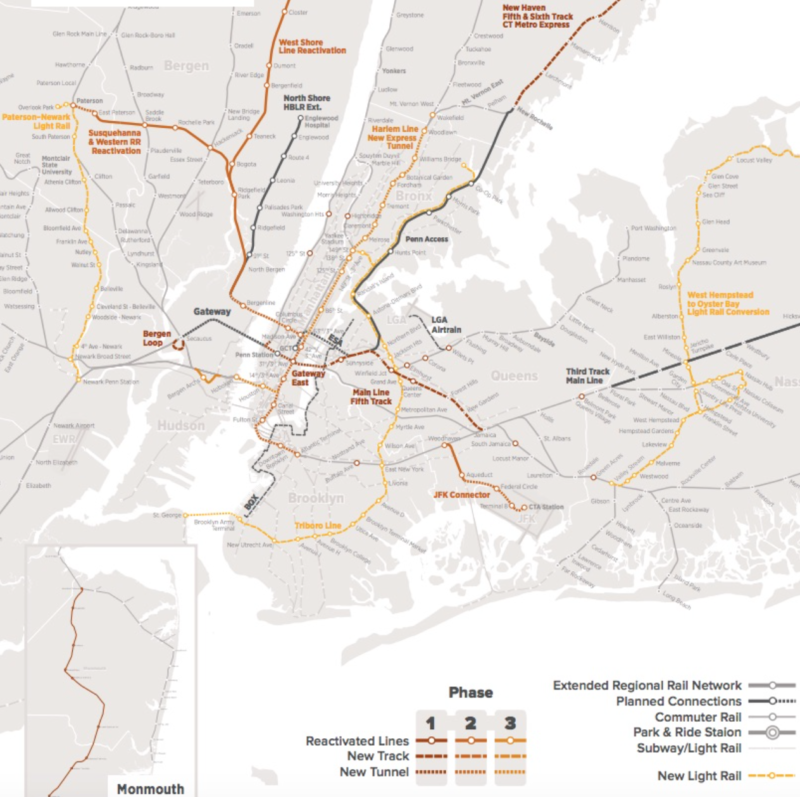

The proposed Triboro Line (in yellow) would connect Brooklyn with Queens and the Bronx

A Triboro rail line, extending from the Bronx to Bay Ridge, would provide new north-south passenger rail service on an existing, underused freight right-of-way, intersecting with 17 subway lines and four commuter-rail lines. By 2040, the RPA suggests, the Triboro Line could serve 100,000 riders daily, with service every five to 15 minutes, opening up new commuting and delivery options. It could cost less than $2 billion, a relatively modest sum.

The RPA posits new stations near centers of activity, including “a revitalized industrial district in Sunset Park, an expanded college campus above the line near Brooklyn College, an expanded mixed-income neighborhood in East New York.”

Outlook: This is somewhat more likely than extended subway service, since the right-of-way already exists and the Triboro Line, a/k/a Triboro Rx or X line, has been on the agenda since the mid-1990s. The Village Voice classified it as among the “five most dramatic pie-in-the-sky transit proposals,” though it seems more likely than the grand plan, illustrated above, to unify regional rail systems, including an extension to JFK airport. After all, the federal government stepped back from financing a planned Hudson River rail tunnel, which is a more immediate need.

4. Improve subway stations

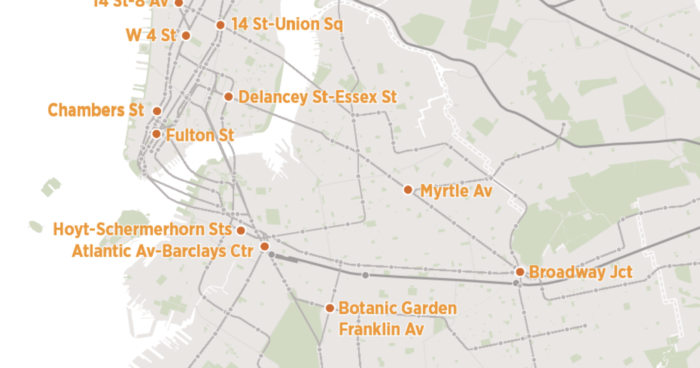

Proposed subway stations for renovation in Brooklyn

Creaky subway stations offer lousy air quality and poor climate control, and must be made compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Of 472 stations, the RPA deems 30 of them to be too congested, requiring larger entrances, wider walkways and redesigned platforms. The Brooklyn stations are Hoyt-Schermerhorn, Atlantic Ave-Barclays Center, Botanic Garden, Myrtle Avenue and Broadway Junction.

Outlook: This requires money, but not nearly as much as extended service, and the deficits are visceral. Public pressure could make such improvements a priority.

5. Create new bus and streetcar lines

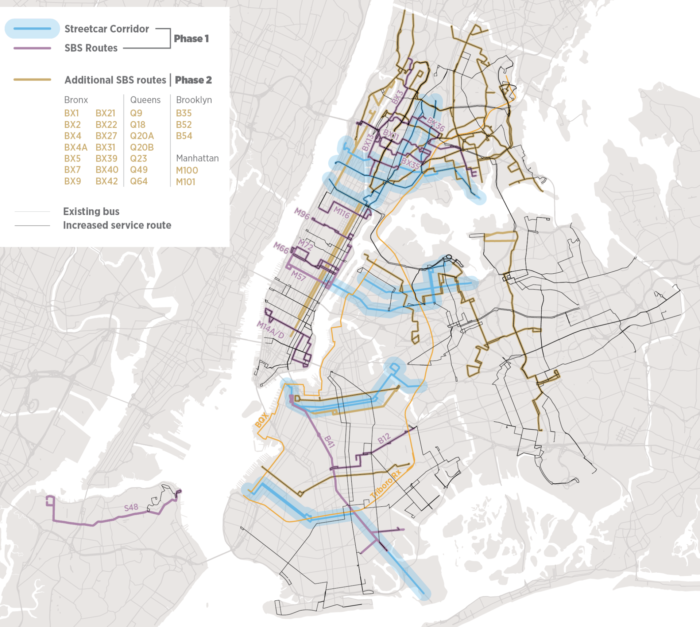

The RPA outlines proposed routes for streetcar and select-bus lines

Bus lines with the highest use and the slowest speeds should be converted, says the RPA, to Select Bus Service (SBS), New York’s version of Bus Rapid Transit. Three such routes are in Brooklyn: the B35 (Sunset Park to Brownsville, on 39th Street and Church Avenue, mainly), B52 (Downtown Brooklyn to Ridgewood on Greene and Gates Avenues, mainly), B54 (Downtown Brooklyn to Ridgewood on Myrtle Avenue, mainly).

As to the proposed light-rail dubbed BQX, from Sunset Park to Astoria, the RPA notes it has “kicked off a lively public debate about reviving rail lines in New York,” and recommends eight more streetcar routes, three in Brooklyn. The text doesn’t pinpoint locations, but the map suggests two routes from Downtown Brooklyn through Bedford-Stuyvesant to Bushwick and Ridgewood, as well as one from Sunset Park through Borough Park to Midwood and Flatbush, then turning down Flatbush Avenue to reach the terminus of the No. 2 and No. 5 trains.

Outlook: Improvements in bus service, which cost far less than new streetcar routes, would come first. Alon Levy, writing in Curbed, suggests the RPA should have looked askance at the BQX, which Kabak thinks won’t be built.

6. Deck over highways, and more

A rendering of the proposed BQGreen in Williamsburg (Image by DLANDstudio)

The RPA recommends decking over key portions of the sunken Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE). Along a six-block stretch between Congress and Union streets in Cobble Hill/Carroll Gardens, new housing could be built. In a long two-block segment in Williamsburg between Bedford and Marcy avenues, the “public realm below and around” the highway could be improved; a park has been proposed.

Beyond that, the RPA recommends turning the Prospect Expressway, for two miles from Third Avenue to its termination at Church Avenue, into a boulevard, allowing for “a new bicycle ‘highway,’ residential development, and public spaces.” The report also proposes that some currently truck-free roads, including the Belt Parkway and Ocean Parkway, be opened up to trucks or at least lighter commercial vehicles, thus reducing congestion elsewhere.

Outlook: It’s not cheap to build a deck, but there is a growing consensus nationally that such highway scars through neighborhoods can be covered up. Taking traffic lanes away from certain vehicles requires political leadership. Locals likely would accept trucks on parkways only if traffic declines in general.

7. Deal with climate change

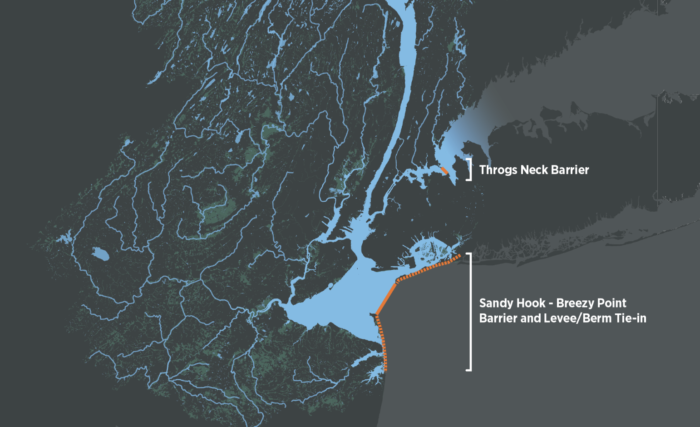

The plan suggests two flood barriers, including one from Sandy Hook to Breezy Point

The RPA suggests strengthening and expanding “the existing carbon pricing system, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative”—which involves nine states capping and reducing emissions from the power sector–“to include emissions from the transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial sectors,” following California’s lead. This could deliver perhaps $3 billion per year in revenue among the three states.

A new Regional Coastal Commission could finally work in a coordinated fashion to protect communities from storm surges and sea-level rise, and to implement solutions at varied geographic scales. Though communities outside Brooklyn are most vulnerable, much of southern Brooklyn from Coney Island eastward faces risks, as do Red Hook, Gowanus and Sunset Park.

The commission would plan for and implement projects by investing revenues from federal and state dollars, as well as new Adaptation Trust Funds capitalized by surcharges on property insurance. The RPA suggests studying the potential for a large–and enormously expensive–surge barrier, such as an “Outer Harbor Gateway” stretching five miles from Sandy Hook in New Jersey to the Rockaway Peninsula.

Outlook: Climate change, a huge, seemingly abstract challenge, likely requires federal as well as state and regional responses. Nearer-term issues likely will take precedent, unless we face another storm–or leaders step up.

8. Reform housing policy

To expand supply, the RPA recommends building on train-station parking lots in the region, adding more than 250,000 units, and allowing accessory units in single-family homes, adding 300,000 units region-wide. The latter could codify the “housing underground” in many working-class neighborhoods, an issue not without controversy.

Also, the report proposes taxing vacant land and vacant apartments, and lifting “arbitrary density limits in the urban core”—allowing taller towers in some neighborhoods in exchange for more affordability. It also recommends limiting short-term rentals, such as with Airbnb, to one apartment per host.

Housing subsidies, it says, should address “the greatest housing needs, such as very low-income rental housing, first-time homeownership, and affordable homes in high-opportunity neighborhoods.” Middle-income subsidies should go to home ownership, where the supply is most constrained, not rental housing. (The recently publicized empty “affordable” units at Pacific Park are middle-income rental units.)

Outlook: This is a complex, politically challenging mix. Some policies require state and regional leadership; for example, as the RPA’s Moses Gates has written, a pied-à-terre tax has died in Albany. Allowing accessory units, however sensible, has been feared as a slippery slope. Bigger buildings face inevitable neighborhood pushback. The city could reform housing subsidies, and has already adjusted its housing plan to focus more on the needy.

9. Maintain affordability

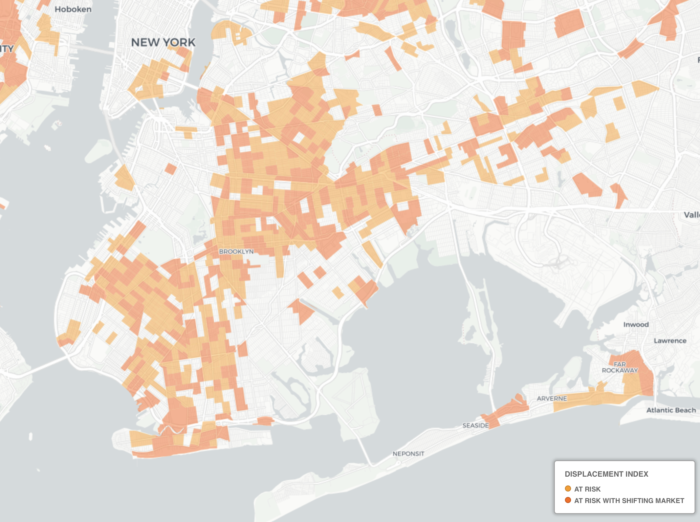

Map shows areas of Brooklyn where risk of displacement of residents is highest

To make the region more affordable, as well as protect low- to moderate-income households (70% of them black or Hispanic) at risk from displacement, the RPA proposes several strategies, including new construction, regulatory changes and new policies. Those at risk include many living in neighborhoods in Brooklyn’s southern and eastern regions.

Public housing in the region needs more than $20 billion in capital funds, which could come from governmental bodies as well as changes in policy, such as new construction on adjacent parking lots.

Outlook: Policy shifts in Washington would be necessary to restore federal funding. Plans to build on parking lots, though politically challenging, have proceeded. While the RPA endorses strengthening rent regulation, it does not address the charged politics behind that, which would require Democratic control of the legislature in Albany.

10. Reform property taxes

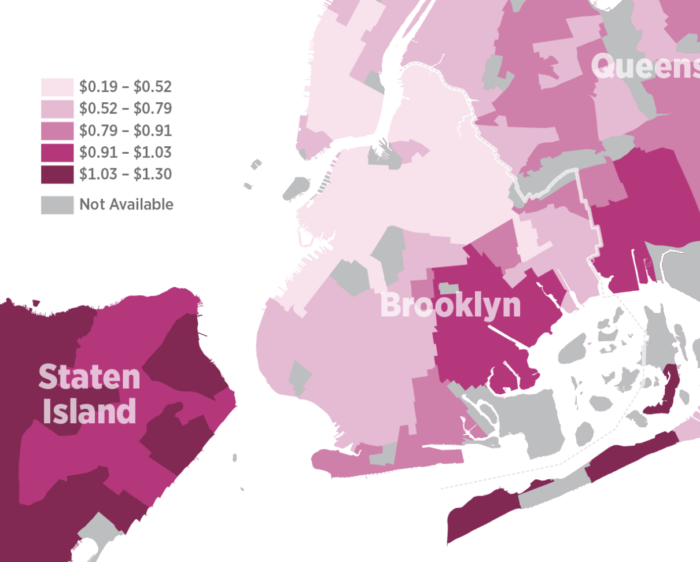

Owners of one- to three-family homes in neighborhoods with lower property values pay higher effective tax rates

As numerous studies have indicated, New York City has unfair property taxes, with homeowners in affluent neighborhoods—Mayor de Blasio’s Park Slope house is often highlighted—paying lower rates than owners of comparable houses elsewhere.

To reform the “illogical and inequitable” system, in which workaday, rent-stabilized apartment buildings pay more than new luxury condos with tax abatements, the RPA recommends that taxes be based on the building’s value, not type, and that renters benefit from any reductions, such as with a tax credit.

This would mean, for example, that the cap in assessed-value increases gets lifted when a building is sold. That policy change could curb housing prices in gentrifying neighborhoods, given increased (or, as the RPA puts it gingerly, “re-sized”) tax bills.

Outlook: Tax reform is politically fraught, but not out of the question, since a court case might force change.

11. Pro-actively clean up aged rental housing

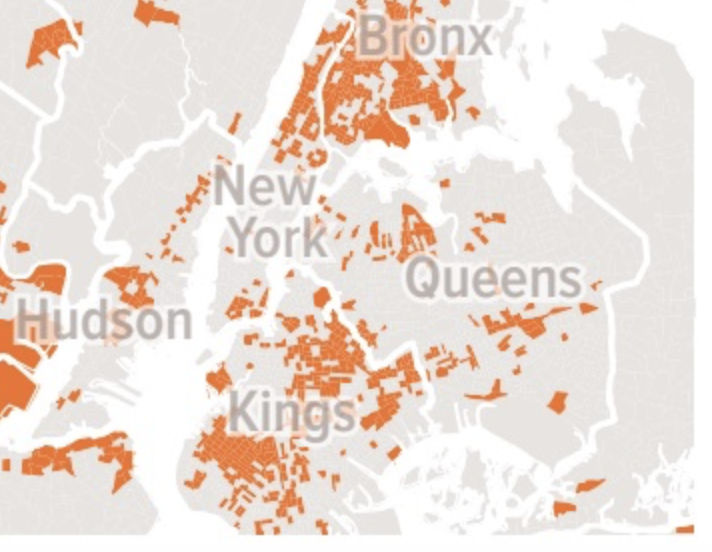

Orange-shaded areas indicate high poverty and old buildings

Given that an older housing stock can mean “high levels of indoor air pollutants, heavy metals, and mold,” and attendant asthma and lead poisoning, the report recommends a proactive strategy, integrating the responsibilities of several disparate agencies.

The RPA proposes that states and counties help localities implement Proactive Rental Inspection programs, which would relieve renters from filing complaints and better deal with absentee landlords. This could affect significant chunks of non-gentrified Brooklyn, as shown in the map. Also, it presumably would mean new business (and jobs) for inspectors and repair companies.

Outlook: Renters have the numerical edge, but the real-estate industry spends far more to influence elections. Public officials would have to make it a priority.

12. Boost internet infrastructure

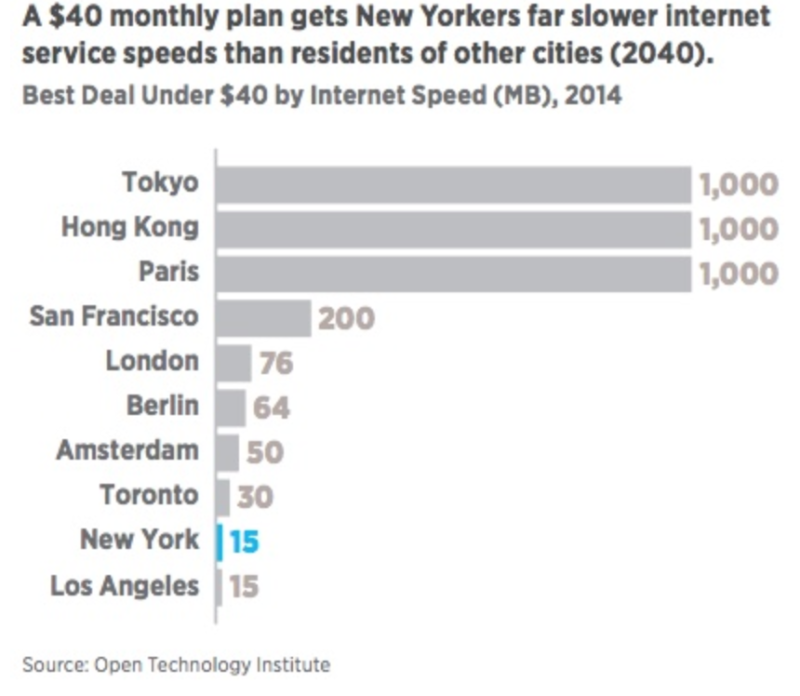

The RPA proposal includes this telling comparison of broadband internet costs

New York’s internet infrastructure lags behind other cities in the U.S. and internationally, and service costs more too. To fix it, the RPA says, the public sector must streamline access to critical infrastructure above and below the streets.

To foster equity, government agencies should support public infrastructure and offer fair wholesale access to that infrastructure. Every building should be wired with fiber-optic cable, enabled by modernized building codes and regulations. An affordable Internet option should be part of municipal broadband and franchise agreements.

Outlook: Construction in New York City is often costly and complicated. If the relatively poor (and expensive) internet service in the city is hampering competitiveness, the tech sector and other businesses could push for improvements.

13. Repurpose city streets

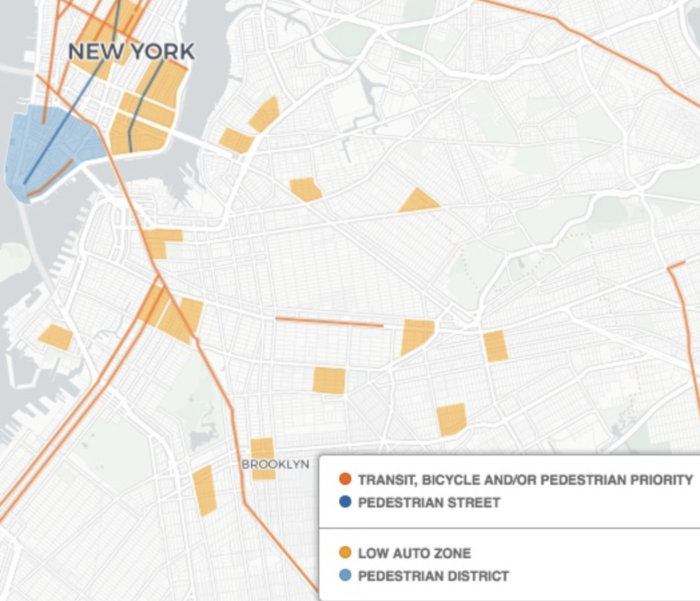

The plan proposes low-auto zones and more bike lanes on the Brooklyn Bridge

Imagine streets no longer prioritized for private vehicles. The RPA suggests that 80% of street space–up from 25% today–could ultimately be devoted to walking, cycling and public transit.

That would mean no more free parking, widened sidewalks, designated lanes for buses, “transit-signal priority and modern fare collection” to speed those buses, citywide bike share, and separated bike lanes. Its map suggests “low auto zones” in, among other places, northern Park Slope and Prospect Heights near Barclays Center, around Church Avenue between Bedford and Nostrand avenues in busy Flatbush, and in Williamsburg’s Southside east of Berry Street to the BQE.

The Brooklyn Bridge should have more bicycle-only lanes, the report says, even if that takes away from vehicles.

Outlook: This surely depends on how much and how fast we transition away from private ownership of cars.

14. Provide new access to public spaces

The report proposes that public spaces, from parking lots to rooftops, be made more accessible: “Existing streets, parking spaces, vacant lots, and sidewalks could be reimagined as areas to play.” Publicly owned buildings could offer meeting spaces to residents, says the RPA.

The city even could open up some of its spectacular properties, such as an observation deck on the Municipal Building. Following BridgeClimb, which allows visitors access to the Sydney Harbor Bridge in Australia, “[s]imilar climbs could occur on the Brooklyn Bridge or another landmark bridge.”

Outlook: Incremental progress should be possible, but security concerns likely would hinder more dramatic action.

15. Shift seaports out of Brooklyn

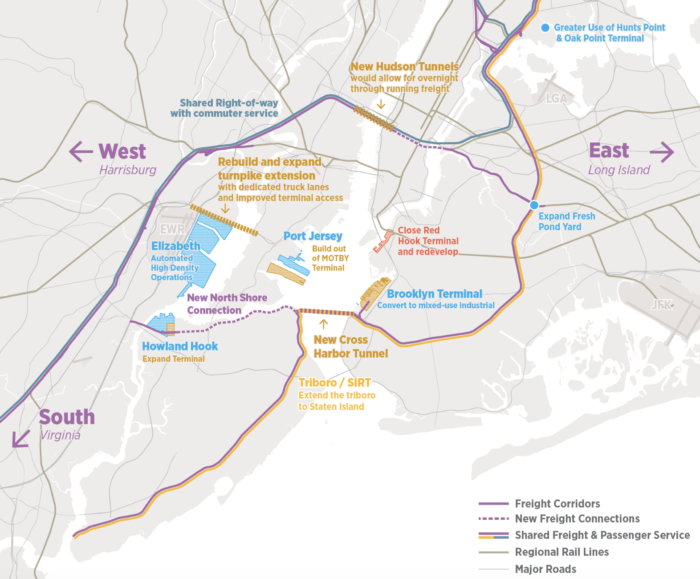

The regional plan includes changes for Brooklyn’s waterfront, plus a new tunnel

The RPA recommends that officials “[c]lose and redevelop both the Red Hook container terminal and the southern Brooklyn (Sunset Park) seaport Facilities,” calling them outmoded and isolated, and proposing that operations be consolidated in in Staten Island and New Jersey. That would free up land for new parks, housing, and light industrial uses.

Wait, there’s more. Building a train tunnel from Bay Ridge to Staten Island could provide freight access from New Jersey as well allow the Staten Island Rapid Transit System link up with the Triboro Line. This would open up more transit to Staten Island and presumably enhance density there.

Outlook: The Sunset Park plan seemingly would counteract the current plan for the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal and imply a regional tug-of-war, though the real estate industry might come up with new plans for Brooklyn. New tunnels are very expensive and way down the line.

16. Move Madison Square Garden (with ripple effects)

To expand and transform Penn Station, beyond even the now-planned Moynihan Station in the Farley Post Office across the street, would require the relocation of Madison Square Garden (MSG) after its ten-year special permit is up in 2023.

MSG surely won’t be relocated until a new Manhattan location is secured but, depending on timing, the construction period could leave the home teams and/or event bookers looking to Brooklyn’s Barclays Center—or perhaps the new arena planned for Belmont Park or even Newark’s Prudential Center.

Outlook: MSG fought hard against limiting its special permit to only ten years, but lost. Its champion in the legislature, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, is gone. The issue seems up to Governor Cuomo, who’s been pushed by crusading New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman, who says that the Garden, “sitting atop the rail hub, smothers its real future.”