How Social Media Became the New 911 Call

In emergencies, New York City increasingly gets the scoop from citizens tweeting and posting photos, declared a panel of experts

Emergency in Brooklyn: First responders attend to passengers who were injured when a Long Island Rail Road train derailed as it came into the Atlantic Terminal in January (Photo by Dave Sanders/The New York Times/Redux)

By the time New York City’s aging 911 system marks its 50th anniversary next year, it will be largely surpassed by the new way citizens interact with authorities in case of emergency: through social media. When fires break out, flash floods strike, or cranes collapse, the city gets its richest and often fastest flow of information from New Yorkers via their mobile phones. “Social is instantaneous,” said Benjamin Krakauer, assistant commissioner for the NYC Office of Emergency Management, speaking on a panel at the TechCrunch Disrupt NY conference today. When it comes to speed, social beats the mainstream media as well. Research shows that “90% of unexpected events break first on Twitter,” said Ted Bailey, CEO of Dataminr, a NYC firm with a contract to help the city listen better in cases of emergency. Coming later this year will be a mobile app for NYC emergencies that “is really going to be a game-changer,” said Krakauer.

Many New Yorkers already use Notify NYC, the system established citywide in 2009 to communicate emergency info to citizens through emails, text messages, tweets and phone calls. The notices cover life-threatening events, health alerts, transit disruptions, and even beach status reports. The notices can be targeted locally or broadcast to dozens of zip codes, as in the case of a synagogue fire on the Lower East Side yesterday that produced smoke visible all over the city, said Krakauer.

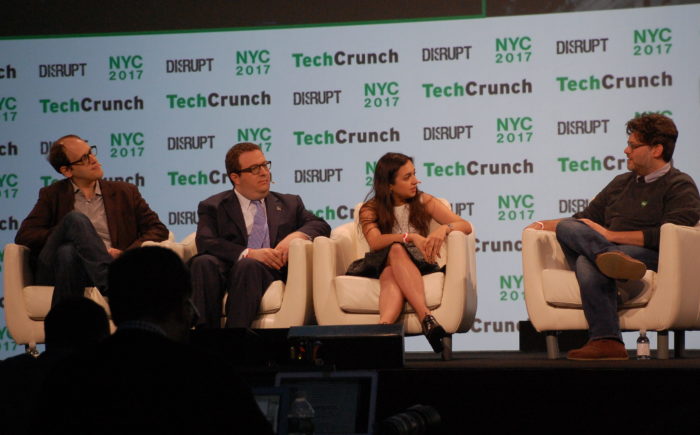

TechCrunch Disrupt NYC panelists talked about the city’s use of social media in emergencies. From left: Ted Bailey, Benjamin Krakauer, Masha Gindler and TechCrunch’s moderator (Photo by Steve Koepp)

As social media has proliferated, the city decided to recruit a tech firm to help authorities gather and understand the data more quickly and clearly. “We’re always looking for new data sources to bring in,” said Krakauer. “We wanted to be able to benefit from all the people tweeting and taking pictures around the city.” The city considered proposals from a dozen potential vendors and awarded a contract to Dataminr for up to $3 million over three years. “We detect that first nugget of information when it first gets published,” said Bailey. The information is “not definitive, but it’s an early trip wire.”

While authorities still want citizens to call 911 in emergencies, social media has provided a much bigger net for gathering information. The city can listen far outside the immediate area for potential trouble, noted Masha Gindler, director of operations for the mayor’s Office of Digital Strategy. For example, the city used social media to track the course of the Zika virus when it threatened South Florida, Gindler said. Slower-moving but still important civic issues can be discovered on social media too. “We’re not just interested in emergencies,” Kraukauer said.

When panel members asked if social media could become susceptible to fake news, Bailey’s response was, essentially, you can’t fool all the people all the time. “What’s most interesting,” he said, “is just how powerful social-media can be to verify information.” Dataminr, which calls itself “the world’s leading real-time information discovery company,” has grown quickly since its start in 2009. The Manhattan firm has 200 employees and has raised $180 million in venture capital.