Inside the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s Epic Comeback

Left for dead a generation ago, the giant industrial park is now overflowing with artists and manufacturers. How it all happened

The 5-Axis CNC router at Situ's fabrication plant in the Navy Yard can create swirly, curving, complex forms (Photo: courtesy of SITU)

I doubt that many Thomas Piketty or Bernie Sanders acolytes know what a 5-Axis CNC router is, but they probably should. Strictly speaking, the router is a robot, though if you’re expecting R2D2, you’ll be disappointed. This machine is more like a robotic surgery device. The patient— usually a slab of plastic, metal, or wood—lies on the bed, where it is “operated” on by a giant drill-like machine suspended from a track above. Following computerized instructions (CNC stands for Computer Numerical Control), the drill grabs the needed “bit” as it moves along the track to cut, trim, and shape the slab/patient. The resulting product is a seat, a domed architectural detail, or whatever it is that its human master is trying to make. The more ordinary and less expensive 3-axis has a drill that can move left to right, right to left, and up and down. Ah, but the 5-axis can go around and create swirly, curving, complex forms. Done by mere humans, these forms would be so time-consuming as to consign them to the category of one-of-a-kind sculpture rather than manufactured object.

Besides its profile of the Navy Yard, Hymowitz’s book charts the comeback of neighborhoods including Park Slope, Williamsburg and Sunset Park

I saw the 5-axis router in action at SITU Fabrication, a company housed in a massive garage still enclosing the train tracks attesting to its former identity as a locomotive repair shop. The space is located in the 300-acre Brooklyn Navy Yard. A mere 25 years ago, the Yard was the perfect symbol of the ruins of the American working class, its 40 or so structures strewn like industrial carcasses from a Mad Max movie. The buildings, used as warehouses and by a smattering of small manufacturing firms, endured regular blackouts, stuck elevators, and roads so cratered that truckers referred to the area as Dodge City. Occasional wild dogs and dead bodies (mob related, one assumes) completed a scene that was more film noir than site of legitimate business.

Enter through one of the five gates of the Yard today, though, and you’ll find scores of young companies like SITU humming with deliveries, projects, plans, and digital machinery. The Yard is now home to 330 small to medium-size manufacturing firms employing 7,000 workers, double what it was 15 years ago. Now if the Navy Yard has one problem, it’s too little usable space. Several large renovations in the works will help. In 2014, Mayor Bill de Blasio pledged $140 million to another addition, Building 77, which will house Shiel Medical Laboratory, employer to 600 people at the Yard, along with other companies. Building 77 will turn a concrete, windowless hulk of a warehouse/ammunition depot into offices and shared work spaces. On the ground floor will be a food hall anchored by Russ and Daughters, New York City’s smoked-fish and caviar emporiums.

Nearby, another group of developers are planning a spectacular modernist glass-and-concrete 16-floor building called Dock 72. Workers in the offices and shared work spaces will be able to take advantage of a basketball court, a specialty food market and cafeteria, a bike valet, a rooftop conference center, and health and wellness facilities. “Our target market is the creative market, the millennial knowledge workers … who are in demand by many of the expanding businesses,” said John Powers, New York regional manager for Boston Properties, one of the developers. Not far away in the Yard is an event space called Duggal Greenhouse. The company’s promotional materials promise customers that they can arrive by car or “yacht … steps from the Duggal Greenhouse and its private waterfront patio.” The site has been used for a Lady Gaga release party, designer Alexander Wang’s fall 2014 runway show, and a 2016 Presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders.

The Navy Yard, Then and Now

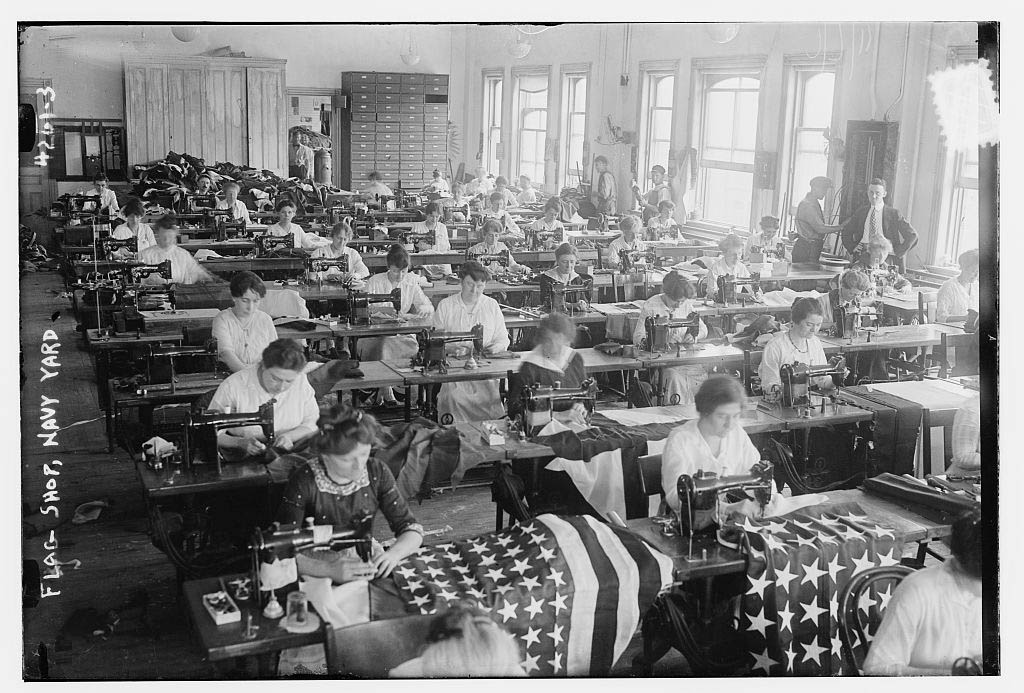

A recovery of the manufacturing sector, insofar as that’s what’s happening, couldn’t find a more fitting spot than the historically resonant Brooklyn Navy Yard. Commissioned by President John Adams in 1801, it was one of the young country’s first military bases at a time when international stature was defined largely by naval power. During the Civil War, the laboring men of the Yard outfitted the USS Monitor, famous as the first ironclad warship, and later the Maine, whose 1898 sinking led to the Spanish-American War. At its peak during World War II, the Yard was Brooklyn’s largest employer, sustaining 70,000 men and women who were electricians, mechanics, welders, and sheet-metal workers and, by extension, their nearby neighborhoods.

Dry dock No. 4 in the Navy Yard, shown in 1910 (Photo: Library of Congress)

But in September 1945, the Japanese surrendered in a ceremony on the USS Missouri, launched from the Brooklyn Yard just 19 months earlier. The event turned out to be symbolic, for as the war ended, so did the jobs of thousands of Brooklyn workers. Given the Yard’s history and its centrality to the Brooklyn economy, it took some time for the federal government to bow to the inevitable; but finally in 1964, the Pentagon announced its closure. By the 1960s, most of New York’s port areas were in decline as well, as costs and outdated infrastructure chased the industry to New Jersey and more distant parts. Still, with its historical significance and its size—not to mention the loss of the borough’s beloved Dodgers a few years earlier—the closing of the Yard came as a serious blow to the borough’s identity.

Workers sewing stars and stripes in the Navy Yard in July 1917 (Photo: Library of Congress)

The closing aggravated the well-known effects of deindustrialization on cities—white working-class flight to the suburbs, rising minority unemployment and welfare dependency, budget crises—which would soon reach a crisis point in Brooklyn. The Ingersoll, Walt Whitman, and Farragut Houses, built by New York City in the 1940s and 1950s to house Yard workers, had coincided with the arrival of poor blacks and Puerto Ricans. Yard workers now had limited job prospects and they became dependent on an overstretched city. Retailers, restaurants, and small contractors in adjacent neighborhoods like Fort Greene, Williamsburg and Greenpoint shriveled up and died. Things didn’t improve when the Yard was turned over to city management in 1969. While a few tenants had stuck through the bad times, the Yard’s condition mirrored that of its fraying home borough. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s and even into the early 1990s, the area was primarily known to car owners as the site of the city tow pound.

Beginnings of a Turnaround

So what led to the resurrection of this old dinosaur of a shipyard? The first real sign of life came in the mid 1990s, when the Yard caught the attention of a Giuliani administration pondering ways to increase the quality of the city’s lower-skilled jobs. They began with a multimillion-dollar infusion for updating the crumbling infrastructure, some of it dating back, if you can believe it, to the Civil War. The administration also revamped the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation (BNYDC), which was managing the Yard. The nonprofit, acting as the Yard’s leasing agent and landlord for more than a decade, had been stuck in an old-industry mind-set.

Now with a bit of nudging from the administration, they got creative. Instead of large manufacturers and warehouse distributors, they focused on finding small, light industrial firms and niche manufacturers that would need workers, hopefully including some from nearby depressed communities. By 1998, BNY had just about fully leased the 4 million sq. ft. of its available space to 200 businesses—though, compared with past numbers, the 3,000 jobs that it generated were worth only a few tepid high-fives.

There was a sign, however, of more, though less traditional, Navy Yard blue-collar jobs to come. Shortly after taking the reins at the BNYDC in 1996, Marc Rosenbaum, a former white-shoe-firm lawyer, was on a trip to Los Angeles when he had a eureka moment. The Yard had plenty of space, and it needed some sex appeal. Why not build a movie studio there? In the minds of doubters, there were many reasons, including that no one, least of all Hollywood machers, was interested in commuting to work in North Brooklyn before the era of hipsters and Jay-Z. “There was a lot of skepticism,” Rosenbaum admits. “People said that soundstages in L.A. were sitting vacant, that digital advances threatened to make the sound stage obsolete. And because soundstages don’t bring in that much, they wondered why anyone would want to lend money for such a project.” Rosenbaum proved them all wrong when Robert De Niro and Miramax studios began negotiating for the acreage. While that particular deal fell through, it wasn’t long before the city was signing a 69-year lease with a local family real-estate firm, Steiner NYC.

If there are people who don’t believe that the results have been, in Rosenbaum’s words, a “monumental success,” they’re not saying so. Employees, including camera grips, sound engineers, set decorators, seamstresses, directors, producers, and actors, drive daily through Steiner Studios’ dramatic entrance-way, beneath World War II radio towers, now lit bright blue like the poles of a giant circus tent. With its ten soundstages, Steiner is the largest television and movie studio on the East Coast. It has been the birthplace of numerous films, including The Producers, Spider Man 3, and Sex and the City 2, and television series including Boardwalk Empire, as well as commercials and music videos. “People with talent want to be in New York,” Rosenbaum observes. “In fact, they’d rather shoot here than in California. Plus we have a tremendous stock of actors. The city had been losing business because of the lack of facilities.”

A worker at IceStone in the Navy Yard puts some polishing touches on a finished slab (Photo: courtesy of IceStone)

Equally, if not more important to the Yard’s upward mobility was the new population of design-inspired, tech-savvy college grads in nearby Williamsburg, Bushwick and Fort Greene. Tom Maiorano, the Yard’s veteran leasing agent, says that he noticed a change in the kinds of tenants looking for space. “It was a generation looking for security,” he said of the older firms owned by immigrants or the sons of immigrants who were now moving toward retirement age. “They did what they had to do—provide for their wives and kids, who eventually became doctors, lawyers, teachers. In the late 1990s, the new tenants were woodworkers, designers, metalworkers. And they were young, just starting their businesses.”

Maiorano was noticing something much bigger than he might have realized at the time. Manufacturing was undergoing a dramatic change. Technology like routers, computer-assisted design (CAD) programs and 3-D printers were making it possible to create physical products quickly, on a small scale, to engage in what is sometimes called “mass customization.” Unlike mass production, mass customization blurs the lines between design and production. Young “creatives”—designers, artists, and engineers—could dream up an idea, cobble together a relatively small amount of capital, buy a router, and open a small fabrication shop. Computers also cut down in the making of prototypes: what used to take months or years can now be done in hours or minutes.

This new manufacturing has considerable advantages for Brooklyn and other “creative” cities. “Because manufacturing today takes much less space, it can become part of the city again,” explains Nina Rappaport, an architectural historian and author of the 2016 Vertical Urban Factory. “You don’t need to keep a large inventory or warehouses, and that can keep you close to clients.” (It also keeps manufacturers within biking distance of employees’ lofts and apartments, an important plus for Brooklyn’s breed of millennial worker.) A study by the Pratt Center for Community Development found that 88% of Navy Yard tenants sell goods inside New York City; those transactions make up an average 71% of these tenants’ total sales. These days, a lot of Brooklyn manufacturing is local.

Makers and the New Brooklyn

And that brings us back to SITU, a perfect example of the new manufacturing. Founded by four millennial Cooper Union architecture graduates, SITU is more like a combination crafts shop, conceptual art studio, and tech company than conventional factory or architecture firm. “Cooper Union gave us a lot of time in the shop; we got used to drawing and making things,” says Brad Samuels, one of the company’s founders. “It helped us to erase the distinction between designing and making. We bought our first router in 2004.” At first, the company did commissions for older artists and architects who didn’t have their “maker” know-how. They went on to produce their own designs: a granite memorial for Flight 587, which crashed in 2001 near JFK airport, mannequins for Marc Jacobs and a “design lab” for the New York Hall of Science in Queens. In 2015, the company got its highest-profile job yet: a redesign of the entrance pavilion of the Brooklyn Museum.

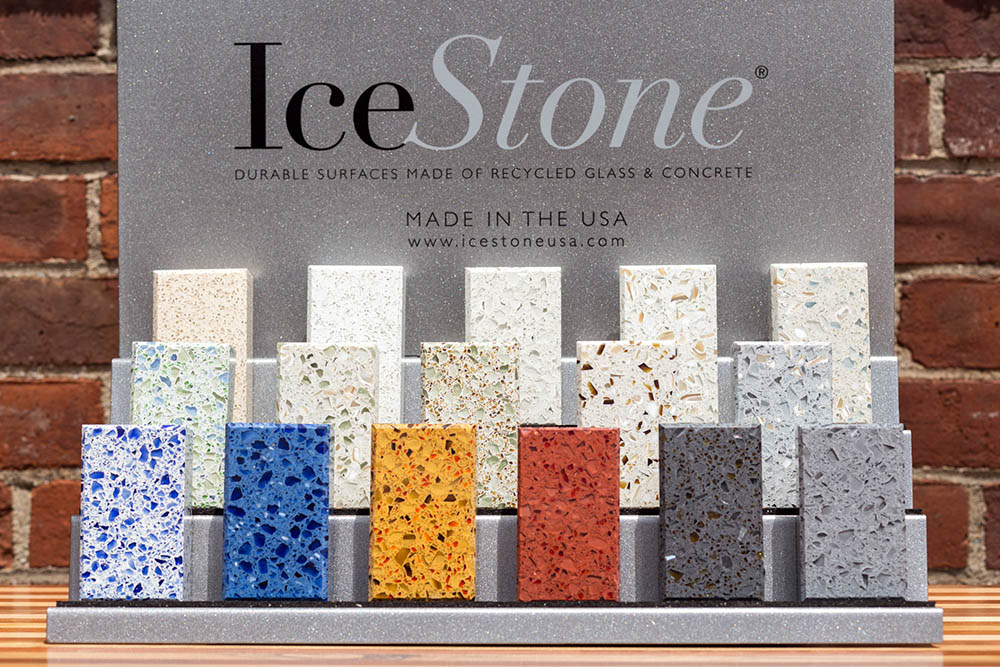

IceStone makes surfaces for counter tops and other uses from recycled glass and concrete (Photo: courtesy of IceStone)

The Yard’s newer tenants also include IceStone, a company that makes countertops of recycled glass; RockPaperRobot, a “kinetic” furniture and lighting company run by an MIT robotics grad; and Ferra Designs (founded by a Pratt graduate priced out of Williamsburg), which makes metal railings, signage and other creations, such as the whimsical schooner-shaped bike racks used throughout the Yard. Among food and beverage companies, the Yard now houses Kings County Distillery (“New York City’s oldest operating distillery . . . founded in 2010,” the company’s website puckishly declares) and Brooklyn Grange, one of the largest rooftop farm companies in the U.S. Andrew Kimball, the highly lauded CEO of the BNYDC in 2005-13, summed up the atmosphere at the Yard: “Making things is cool again.”

Several companies at the Yard deploy technology in ways that recall the Yard’s military origins. Honeybee Robotics, for instance, has developed robots for NASA, hospitals, and mining companies. Another military contract business, Crye Precision, may be one of the biggest success stories at the Yard. Crye designs and manufactures advanced protective military clothing, including helmets with cameras for Special Forces, removable chemical weapon protection, communication devices, and MultiCam, a newly designed all-terrain camouflage pattern used by the Australian military and the U.S. in Afghanistan. Caleb Crye, who has been called the “Steve Jobs of tactical gear,” and his partner moved to a 1,000-sq. ft. space in the Yard in 2002. As their company grew, it was forced to scatter its operations to different buildings, a situation that was rectified when they were able to consolidate into a new 85,000-sq. ft. space in the Yard in 2016.

How Many Jobs Will Come Back?

Yet Brooklyn’s new manufacturing isn’t close to recouping the city’s blue-collar losses over the past 60 years. In fact, according to Jonathan Bowles of the Center for an Urban Future, between 1997 and 2010 New York was continuing to shed at least 5,000 manufacturing jobs a year. By 2010, the decline had halted in New York City as a whole and actually reversed itself in Brooklyn.

It scarcely needs to be said that this is not your grandfather’s Navy Yard. During its manufacturing heyday, Brooklyn was able to employ generation after generation of poor immigrants and bring them to the threshold of the middle class. At least on a large scale, that scenario seems unlikely today, though not because gentrified manufacturing is displacing old-timers.

No, the problem is that new manufacturing doesn’t rely on a low-skilled workforce in the same way that old manufacturing did. For one thing, it needs far fewer workers; that 5-axis CNC router and other productive technologies consign many low-skilled jobs to history. In 1999, Scott Jordan, whose eponymous company has been making Shaker-style wood furniture in a former cannon factory at the Yard since 1988, brought a 3-axis router that cuts one of his trademark chairs in 20 minutes. That and a slow economy reduced his staff from twelve to six in 2015. Since the beginning of this century alone, the number of people hired by businesses has been sinking; Brooklyn averaged 11.2 workers per business in 2011, compared with an average of 16.8 workers in 2000.

Another reason for doubting the revival of a familiar blue-collar economy is that manufacturing jobs require more advanced skills than the smokestack-company grunt work of the past. The Yard’s SITU partner Brad Samuels notes that each project they take on uses different materials and different processes; he needs people who can adapt. Recently graduated artists and architects looking for experience in advanced manufacturing often take those lower-level jobs. The day that I visited SITU, I saw about 15 workers; they were almost all young and white, straight out of Williamsburg central casting. The Yard’s employment center places only about 300 people a year; a quarter of those are from nearby housing projects. It’s not much.

This doesn’t mean that there are no opportunities for low-skilled Brooklynites in gentrified manufacturing centers. Crye Precision’s MultiCam vests, for instance, are hand-sewn by seamstresses, most of whom commute from Sunset Park’s Chinatown. David Ehrenberg, the newest CEO of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corp., was upbeat when I interviewed him in 2015: “Modern manufacturing … requires more and more skills, but it still has a wider skill band than in other sectors. And these are skills that lend themselves to on-the-job training. People progress from lower down watching and learning, graduating to laser cutter.”

Meanwhile, employers say that they can’t find enough workers capable of doing the jobs that are available. Governments can do a number of things to encourage more middle-skilled training and position. First and foremost, they can bring back what Old Brooklyn (and elsewhere) called vocational education but what has now been rechristened “Career and Technical Education” (CTE). Starting during the Bloomberg administration, New York City greatly expanded CTE. The programs emphasize partnering with local business and work-based learning. They’re beginning to show signs of success. CTE is probably the best hope we have for placing the less skilled in decently paying careers. It should be a top policy priority.