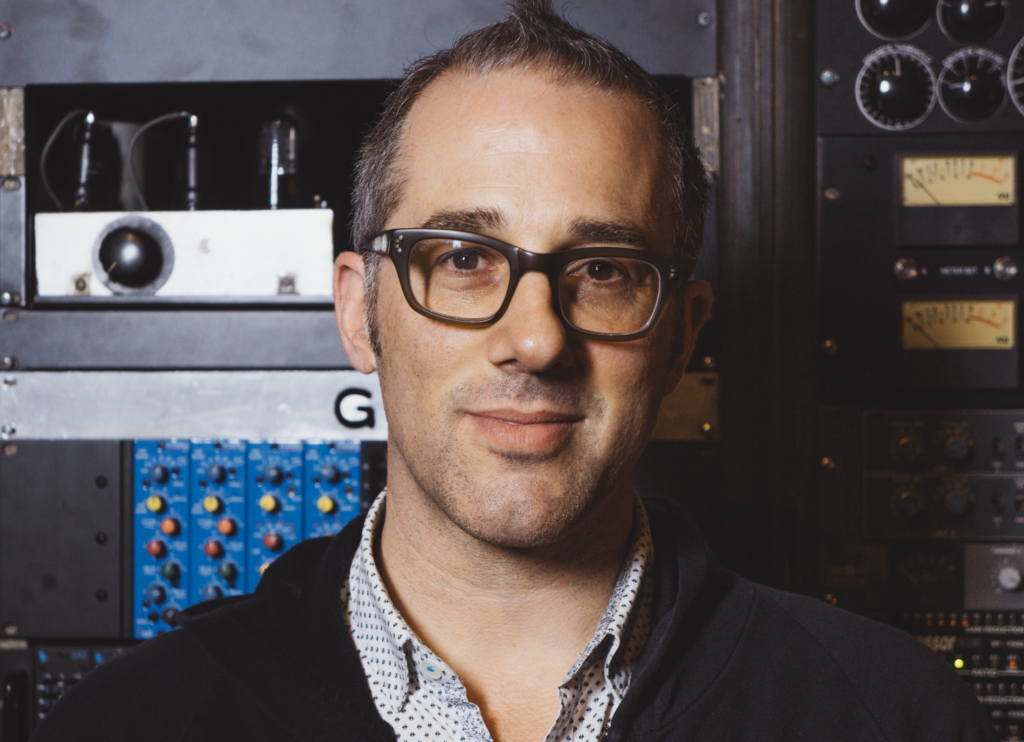

You’ve probably heard music that was recorded at Studio G Brooklyn, the legendary sound laboratory tucked into the border of Greenpoint and Williamsburg. Clients of the space have included Aaron Neville, Bonobo, Ani DiFranco, Tom Waits, Talib Kweli, Sesame Street, Spotify, and many more. Our podcast guest Joel Hamilton, an acclaimed producer and engineer who owns and operates the place along with Tony Maimone and Chris Cubeta, told us how the sophisticated studio was built from scratch over the last two decades.

Studio G was hip from the start, before Williamsburg or Greenpoint were what they are today. The founders had the good fortune, Hamilton acknowledges, of getting started in the right place at the right time. “For me to comment on the studio business is for me to comment on a very personalized trajectory that operated within a very, sort of, DIY scene,” he said, “and then expanded when the DIY scene ultimately bubbles up from the underground and becomes ‘cool.’”

It wasn’t blooming from the beginning, though. Hamilton recalled the Brooklyn nobody knew, as it went from the destination to which “you had to argue with the taxi driver to go over the Williamsburg Bridge” to the place “where everyone wanted to be.” The early days were largely about finding artists willing to make the trek. “That’s a part of the story: convincing people to come to Brooklyn. It’s not like it was the middle of nowhere, it was actually scary to some people. It was worse than nowhere.”

Their location, along with being the new kids in the business, meant that a large source of early clientele were Hamilton’s own friends. “When you’re in a band, it’s usually your friends’ bands are the bands that are coming in to record with you, so that’s a double-edged sword,” Hamilton said. “You have access to more people who need recordings and less people who are going to pay you. You just keep the overhead low.”

Slowly but surely, Studio G built a stronger resume and Brooklyn started to shift. “There was this groundswell of relevant artists that were living in the cheaper neighborhoods out here because the East Village got expensive. Our business model kept evolving to support that new breed of kid that was starting bands in Williamsburg. We just happened to speak the same language. We came from the same set of influences and had enough gear that we could get the job done for them.”

The studio’s infrastructure grew almost as a direct reflection of the community surrounding it. “I had really broken stuff and that was serving a community that could only afford the kind of broken stuff, and therefore they were more patient with me having to kind of make it work,” Hamilton recalled. “And then we moved to the next level because that process and those bands’ patience got me to the next level,” he said.

Soon, artists with higher budgets started coming in. “They were a little less patient with my broken shit but they had a little more money to spend. And so I would take a percentage of that budget and put it into the next vocal microphone or mic pre[amp] or piece of equipment that sort of pushed me to the next level on the infrastructure side.”

Even as the business has scaled up, the ethic has been the same: make the most of the resources you have. “For me the game has always been: If you have $500 available to make a record, make it sound like $1,000. If f you have $1,000 make it sound like $5,000. And that applies even now. If you’re doing a record with a $100,000 budget, you have to make it sound like it had a million-dollar budget.”

The philosophy seems to have worked. Hamilton has been nominated for seven Grammy awards.—By Kora Feder

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS