The Remarkable Recovery of Business in Red Hook

Part 2 of a special report: Five years after Sandy, the scrappy proprietors tell how they fought their way back–and how they'll deal with rising seas

Susan Povich, owner of Red Hook Lobster Pound, with a reminder of the storm surge (All photos by Timothy Fadek)

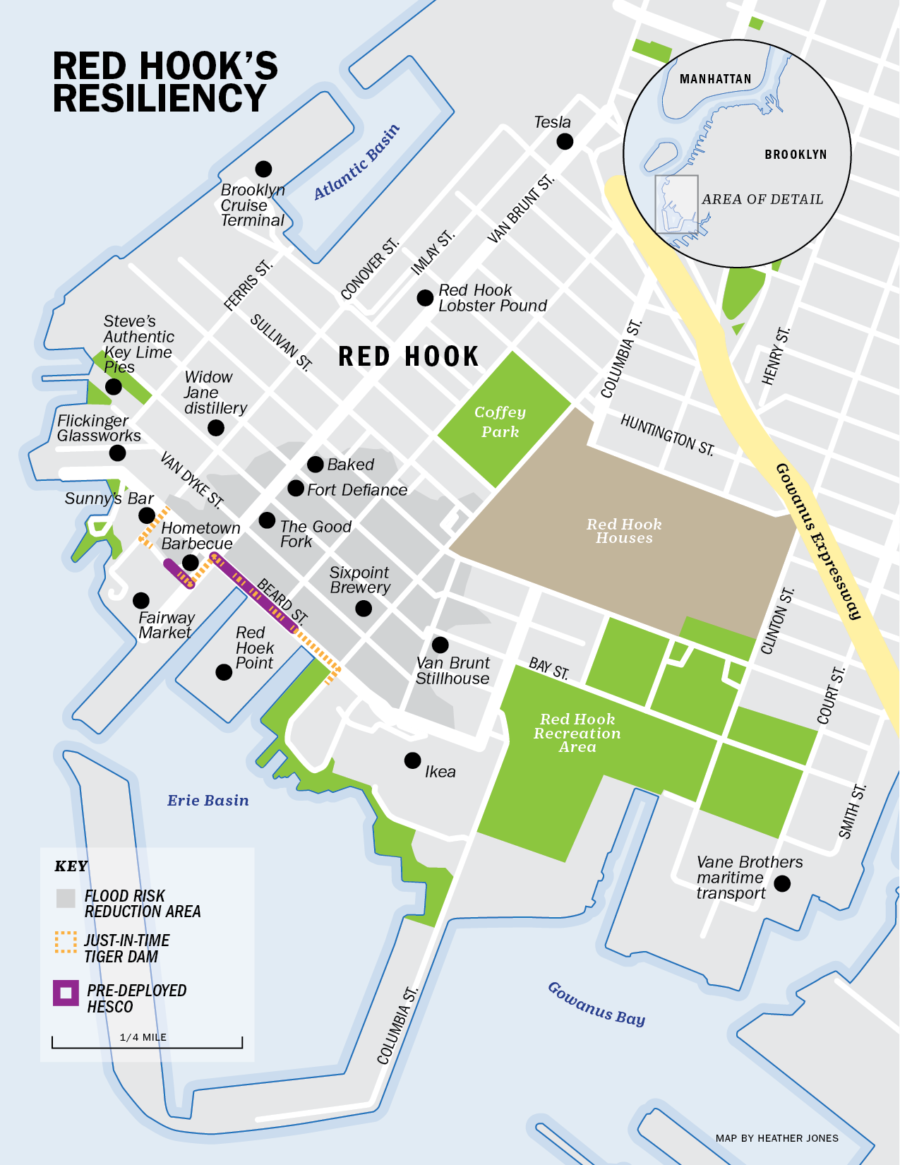

On that blustery October afternoon, a few days before Halloween 2012, the forecasts were grim. Mandatory evacuation orders were in place for nearly the entire neighborhood of Red Hook, Brooklyn. With newscasters and city officials warning that Hurricane Sandy could bring historic devastation, business owners grabbed the last of what they could and evacuated by the 5 p.m. curfew.

Some stayed to ride out the storm. As she watched the water lap over the shoreline, Tone Balzano Johansen, owner of the iconic bar, Sunny’s, went down to the basement to put valuables on a table. She recalls that for a moment, it was eerily calm. Around 9:30 p.m., at high tide and with a full moon, the sea lifted. A storm surge of more than 14 feet sent a cascade of seawater rushing into Red Hook.

As Johansen worked in the basement, she heard a loud “pop.” A window shattered. Water gushed in with a ferocious velocity. “I had to get ahead of it. I could see the electric meters right there. There are two dangers: you can be electrocuted and you can get trapped. Zapped and trapped, and you’re done. ” She ran up the stairs. “It was like I was flying. I very narrowly made it out of there.”

Ben Schneider, co-owner of The Good Fork restaurant

Dozens of small businesses near the harbor filled with saltwater. The surge receded quickly, but the devastation was done. Many companies lost nearly everything in the fast-moving flood: computers, trucks, food, furniture, office equipment, documents, a grocery store’s vast inventory. Most did not have flood insurance and those who did fought for scant payouts. Four inches of snow fell three days later, and parts of the neighborhood were without power for weeks.

Part two of a three-part special report from The Bridge

The night of Hurricane Sandy launched an arduous, and costly, cleanup for businesses throughout Red Hook. As the fifth anniversary of Sandy approached, The Bridge talked with owners and managers about the quick decisions they had to make that night, the damage they found the next day, the lessons learned, and preparations for future battles with the sea.

Things Began to Float

Days before the storm hit, employees at the Red Hook outpost of Vane Brothers, a Baltimore company that operates a fleet of 12 tug boats and 20 barges in New York Harbor, worked to secure their vessels so they wouldn’t get tossed to sea. But managers realized at the last minute that they hadn’t considered the office building, situated at the south end of Court Street. The night of the storm, crew members handling Vane’s tug boats watched as water flowed into the company’s office. They’d put things up on desks, but “we had 38 to 40 inches of water in the building. The desks started floating and tipped over,” said Fleet Manager John Bowie.

Two large, rolling steel doors buckled under the weight of the water. Bowie returned the next morning to “an overwhelming sight, a really unbelievable sight.” While he could see the water line on the wall and only a few puddles on the floor, everything on the ground level was ruined or gone. The sea water had swept away equipment, furniture, computers, and paperwork. Some 20 vehicles were flooded, most of them totaled, Bowie said.

John Bowie, fleet manager of Vane Brothers maritime services in Red Hook

On the other side of the neighborhood is the 7,000-sq.-ft. industrial studio of Charles Flickinger, a world-renowned artisan, one of the few in the world who can bend glass for custom projects like the clock faces in Grand Central Terminal. His studio is situated on Pier 41, in a brick warehouse dating to the 1800s that juts elegantly into the New York Harbor. As Hurricane Sandy approached, Flickinger put sandbags up two feet high around his doors and boarded the windows. His wife grabbed computers on the way out. Everything else was sacked, he said. “It was a disaster,” Flickinger said. Drawers and machinery were filled and covered with water, oil, and raw sewage. The company lost $250,000 worth of equipment–custom gas ovens, automatic polishing equipment, motors. Fortunately, glassmaking molds from the 1830s, made of steel, survived the storm.

On Van Brunt Street, the neighborhood’s main drag, owners of the Red Hook Lobster Pound, which had launched in 2008 in the midst of the great recession, returned the morning after the storm to see dead lobsters floating in the muck. They lost nearly everything in the restaurant, as well as several delivery vehicles. Down the street, the husband-and-wife, carpenter-chef team of Ben Schneider and Sohui Kim, owners of the celebrated The Good Fork restaurant, returned to find the restaurant like a swimming pool. A 9′-by-9′, walk-in refrigerator was floating in the water, contents destroyed. Schneider rode on his freezer like a boat, he said, to go fetch a pump.

To Rebuild, or Give Up?

The prospect of cleaning up and rebuilding was daunting, even for Red Hook’s gritty, DIY types. Shane Welch, founder of Sixpoint Brewery, which suffered work-stopping damage to pumps and machines, said it was difficult even to get the repair process started. The city’s supply chain of parts and labor became heavily back-logged. “For a good couple of weeks, you had to wait 45 minutes to fill up your car with gas. The whole city turned into a Mad Max kind of thing. Red Hook in particular, because we were without power for a while,” Welch said. “Without power, you are totally screwed. You can’t do a lot of basic stuff.”

The cleanup “was a long, arduous slog,” glassmaker Flickinger said. “We lost a fair amount of business. Our customers had to go elsewhere. It was a great hardship for us.” His neighbor on Pier 41, Red Hook Winery founder Mark Snyder, said his winery was devastated and lost three vintages of wine. “I made an early commitment to recover. I didn’t want to disappoint my employees and all the small growers I had been working with since 2008,” he said in a Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce panel discussion this week on storm resilience for small business. But Snyder’s early estimate of the damage, $1 million, grew to $2.8 million. He said he had no flood insurance because he had been misled about what flood insurance actually covered, “so I didn’t get it.”

Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez, whose district includes Red Hook, spoke at this week’s panel about the critical early days of disaster relief for small business, perhaps analogous to the “golden hour” after a person suffers traumatic injury. “If you don’t get the assistance you need in the first three to four weeks, the probability of your business shutting down is very high,” said Velázquez, who serves as ranking member of the House Small Business Committee. In the case of disasters, loans from the SBA do not come fast enough, she said. “We are still dealing with a process that is really slow.”

Tone Balzano Johansen, owner of the iconic bar Sunny’s

“After every disaster, the first thing a small business needs is the capital to recover,” agreed Gregg Bishop, commissioner of city Small Business Services, who spoke on the panel. But in the case of Sandy, government agencies were swamped. “The problem with Sandy was that it was a disaster in multiple areas,” he said. At the same time, business owners seeking loans were often lacking the necessary documents, like income statements, because their computers had been ruined by saltwater. Even some companies with insurance, who had kept their policies up to date, were left hanging. “The insurance companies weren’t there for them, and I find that to be criminal,” Bishop said.

In Red Hook, volunteers came to the rescue of the business owners, who held fundraisers and launched online crowdfunding campaigns. “The extent to which people came to our aid was incredible and moving,” The Good Fork’s Schneider said, “both in physical labor, and financially. We all had to dig in and work ourselves to the bone to get on our feet. When I think of all the people who helped us, it was quite incredible.” Said the Red Hook Winery’s Snyder: “The most important lesson was to rely on community and myself and not wait for the federal government.”

In the storm’s immediate aftermath, PortSide NewYork, a waterway advocacy group and custodian of the historic 1938 tugboat Mary A. Whalen, set up an emergency center to aid small business, winning a Champions of Change award from the White House for the effort.

Lessons for the Next Time

Red Hook business owners say they’ll watch the weather more closely now, and do things a little differently, if another major hurricane is predicted. “We should have evacuated,” said Johansen, the Norwegian artist and owner of Sunny’s. “But the year before, with Irene, we all got stuck out in Jersey, and it was a pain getting back, and then it wasn’t as bad as they thought.”

Nearly everyone was unprepared for the wrath, but they’ve learned from the experience, and from neighbors. “It was acutely painful to me to see how hurt my beloved Red Hook was, when it didn’t have to be,” said Carolina Salguero, PortSide NewYork’s director. “As mariners, we understood the weather and we were preparing for four, five days,” she said. “Take the computer out of the cellar. Turn the power off in your building. Secure your fuel tank so it doesn’t float. Remove important documents,” she said. Move vehicles to higher ground. “That’s what we wish that people knew to do. And I hope they do now. Before you can get into preparations, you have to understand your vulnerability.” The Lobster Pound’s Povich said that in retrospect, she wishes she’d moved more inventory and her delivery vehicles. But as the storm approached, anxiety and panic got in the way, she said.

Povich outside her Red Hook flagship, which now has outposts in Manhattan and Montauk

Several owners said they learned that, to some extent, it’s futile to try to hold back the sea. “I’d probably leave the steel doors open a few feet,” said tugboat operator Bowie, to let water wash through without buckling the doors. “The water is going to come in anyway.” Flickinger, the glassmaker, agrees. “Our idea is to let the water wash in, and get it out as quickly as we can,” said the artisan. He’s got a storage room full of pumps, generators, and head lamps, should the need arise.

Some have made physical changes in their buildings to keep vital components above water. In the rebuild, Schneider rented a lot next door and installed a new walk-in fridge, up on stilts, but there are limits to changes he can make. “A lot of our operations are in the basement. There’s nowhere to move them,” Schneider said. If another big storm is predicted, Flickinger said, he’ll “jack up the machinery and put it on cinder blocks.”

At the Lobster Pound, an innovative “resilient power hub” will be installed on the roof by energy consulting firm Bright Power, thanks to a grant from RISE:NY, a city program to help small businesses become more resilient. At Sunny’s bar, Johansen’s back-up technology is modest: a crank-powered light with a USB port for charging a phone. “What am I doing to prepare for the next one? I’ve not hardly recovered from the last one. At least I have something,” she said, motioning toward her emergency light.

Facing the Rising Tide

Schneider says he’s not sure The Good Fork will remain in Red Hook if there’s another big flood. “We might decide to move to a different spot that’s safer,” Schneider said. In the meantime, however, he’s like most of the Red Hook entrepreneurs The Bridge interviewed: stoic and a bit fatalistic. “Fear, there’s not much a point of that. There are other things to worry about. We are lucky to have modern forecasting. We know when it’s coming.”

Make an aerial visit to Red Hook via our drone-powered tour of the neighborhood

“We will deal with the hand we’re dealt,” said Bowie, who has worked in the New York Harbor for 30 years. Said Povich: “That’s part of choosing to be in the flood zone. If you want to live on the water, this is the risk you take. And it’s a lovely place to be.” Povich owns her building, which made a difference last time. She says she might not have rebuilt if she were a renter.

“Red Hook is not like any other neighborhood,” Flickinger said. “Anyone who moved down here to do business is pretty scrappy. Everyone is doing things with their hands. Nobody is getting rich. You do what you can to prepare, and you try not to live in the wreckage of the future.”

Sixpoint’s Welch, for his part, has indeed been thinking about the future, given the “almost Biblical” nature of recent natural disasters. “New York is particularly vulnerable. There are a lot of low-lying areas. Red Hook is one of them,” Welch said. “Am I worried? Yes. But I’m not so worried about our business and Red Hook. I’m more worried about New York.” People tend to forget, he said, that Sandy had been downgraded to a tropical storm by the time it hit, and didn’t hit directly. “If it were a Category 4 hurricane that had a direct hit on Brooklyn or Manhattan, that would probably have wiped out the city. If New York got what Houston got, there would have been several million displaced people.”

“New York is the economic engine of the country,” Welch continued, advocating a big-scale approach to protecting New York from that kind of flood. “That would be crazy. That would be a natural disaster like we’ve never seen. I hope the leaders and local government are getting out in front of this.” We should perhaps look to the Dutch, he said, who “are crazy good at this. All the port cities have a series of canals and locks, so they can control storm surges and protect the city. New York is going to need something like that.”

Povich agreed about studying dikes and generally fortifying Red Hook, but is reconciled to the limits of what can be done. “The water is rising,” she said. “Come on, how can you stave off the ocean?”