So you opened a small business in the neighborhood where you’ve lived since you were a kid. Maybe it’s in East New York. Because your roots are so deeply entrenched there, because you understand what your neighbors want and need, your dream business takes off. Could be a corner store, a hair salon, a day-care center, a bar or restaurant. Over the course of the ten-year lease on your storefront, you’ve built up a community of regulars and enjoyed plenty of walk-in traffic from newcomers to the neighborhood. You’ve hired a staff of three full-time employees so you can have dinner every night with your kids. Maybe you’ve started socking money away for a down payment on a home.

But now, 10 years later, your lease is up for renewal. And because East New York has become one of the fastest-developing neighborhoods in the five boroughs, commercial rents in the area have been on the rise. Your landlord, with whom you’ve had an amiable relationship for years, is demanding a rent increase you can’t afford—at least not without jacking up your prices to the point where you’ll scare away your customers. “It’s not personal,” the landlord tells you.

You consider laying off your employees—mothers and fathers themselves. You think about reopening elsewhere, but with no assurances your business will translate in another neighborhood. You also contemplate the grim option of closing the business altogether, with the prospect of seeing a cash-flush business—perhaps a national chain—occupying the space you’d built into a local institution.

In April, elected officials and community leaders rallied on the steps of City Hall in support of the SBJSA (Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation/Flickr)

Melodrama? No, a sadly common situation, according to proponents of the Small Business Jobs Survival Act (SBJSA), which they hope will provide a remedy. First proposed in the City Council over 30 years ago, the SBJSA would provide protections for small-business owners in their lease renewal negotiations. Among other conditions, it would require commercial landlords to inform their tenants 180 days in advance of a lease expiration whether they intend seek renewal. (The provisions of this chapter apply to any landlord and current tenant whose lease expires on or after Jan. 1, 2019.)

If a landlord doesn’t wish to do so, they’d have to provide valid reasons as to why, such as late rent payments or a history of criminal activity on the premises. If the tenant is in good standing, they’ll automatically qualify for a new 10-year lease, and if a rent rate cannot be agreed upon between the tenant and landlord, an independent arbitrator will establish one for them.

The SBJSA, which is currently being reviewed in the City Council’s Committee on Small Business, will get a hearing at City Hall on Mon., Oct 22. A preceding rally organized by the advocacy group Friends of the SBJSA will take place on the landmark’s steps at noon. While the legislation has been in limbo for three decades, the current City Council speaker, Corey Johnson, vociferously supports the bill, and its proponents are making a last-ditch campaign for it.

“This bill is going to save small businesses,” Friends of the SBJSA founder David Eisenbach told The Bridge. “It will stop the extortion; it’ll stop the massive turnover and turnout of mainly immigrant-owned businesses, which is what we’re seeing particularly in neighborhoods that have been rezoned.”

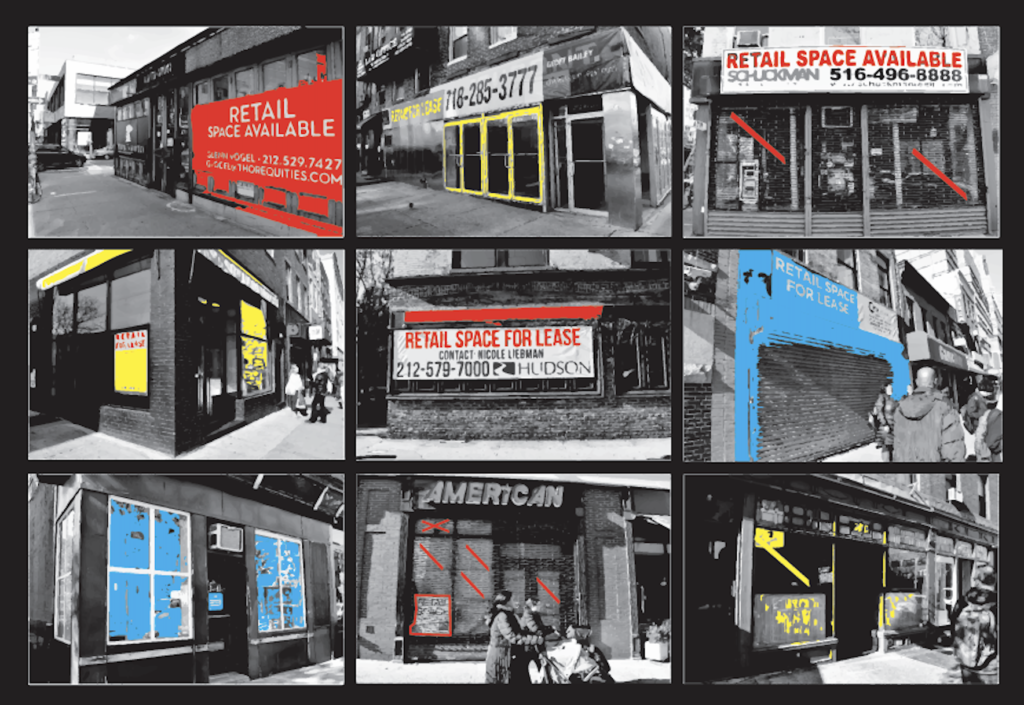

While small business has been under strain because of rising rents, an increasing number of chain stores have taken their places (Illustration by Heather Jones. Photos by Arden Phillips)

The northwest corner of Brooklyn, including Williamsburg and Greenpoint, famously underwent a rezoning 13 years ago, leading to a wave of rent hikes in both the residential and commercial sectors. According to commercial real-estate market reports published by TerraCRG, a brokerage firm that focuses on Brooklyn commercial properties, between 2010 and 2017 the average price per square foot of retail space in Williamsburg and Greenpoint went from $166 to an astronomical $1,710.

While that’s on the extreme end compared with other parts of Brooklyn, rising rents citywide have brought economic pressure on small businesses to the point of squeezing out their profit margin. The failure of such businesses has contributed to a new kind of urban blight: empty storefronts in prospering neighborhoods. Last month the New York Times cited a study showing that 20% of all retail space in Manhattan is currently vacant, up from about 7% from just two years ago.

City Council Member Rafael Espinal, who helped push through rezoning legislation for East New York, part of the district he represents, supports the SBJSA as “the first step in addressing the vacancy crisis head-on,” he told The Bridge in an email.

“I’m committed to finding even more legislative solutions to address the skyrocketing rents and commercial tenant harassment that so many small business owners face,” Espinal wrote. “Keeping our local shops open helps keep our neighborhoods affordable, and build a sense of community.”

The case for the bill is not just an economic one, according to many supporters, but an aesthetic and cultural one as well. “What I like about the SBJSA is the positive impact I believe it will have on small business people and the streetscape of the city,” Jeremiah Moss, author of Vanishing New York, the book and popular blog about the city’s ever-changing landscape, said in email. “The bill gives existing commercial tenants in good standing a few basic rights,” Moss continued. With it in place, “a landlord can’t just refuse to renew a lease, as they often do today. They can’t just double, triple, quadruple the rent, as they also often do today.”

Moss also noted that the bill protects small businesses of many varieties, from ground-floor retailers to manufacturing tenants to artists renting a penthouse loft. Moss also wrote that he works as a psychotherapist and “lost my office space to a luxury developer.”

Indeed, while the prospective beneficiaries of the bill are typically portrayed as established mom-and-pop shops, a newer generation of entrepreneurs has a stake in the issue as well. Says Max Friefeld, CEO of Voodoo Manufacturing, a 3-D printing company in East Williamsburg: “Small businesses and manufacturing are the foundation of any strong local economy. We’re excited to be in New York City, employing New Yorkers, and we want to stay.”

An Opposition Argument: It’s Not Legal

The reason the SBJSA has languished without passage in the City Council for so long, according to its supporters, is staunch opposition to the bill from “Big Real Estate,” typically personified by the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), the industry’s leading trade association. In a statement emailed to The Bridge last week, John Banks, REBNY’s president, said that the SBJSA is “illegal and ignores market conditions.”

“Vacancy rates fluctuate among individual retail corridors and rents are, in general, decreasing,” his statement continued. “The Council should focus its limited time, energy, and resources on solutions that will support small businesses instead of wasting millions of tax dollars defending an illegal bill that experts agree will be thrown out by the courts.”

Among those experts would be the New York City Bar Association, an organization of 2,400 lawyers and law students, which recently published a report that called the SBJSA “commercial rent control” —a label frequently used by the bill’s detractors in the press. The bar association committee that studied the bill determined that the city would be empowered to pass such legislation only by a concern for “health and welfare” and that “previous attempts by the City Council to enact residential rent controls–which the committee maintains are closer to concerns of health and welfare than are commercial rent controls–have already been struck down by the courts.”

Other opponents of the SBJSA object to the way the law is written. In an op-ed for the Commercial Observer, Steven Kirkpatrick, a member of the bar association, slammed the SBJSA for its lack of clarity on the origins of funds for prospective arbitration hearings, as well as its ignoring of the spectrum of commercial-tenant types. “So, a national retail chain store is granted new property rights and powers under the act just like the neighborhood pizzeria,” Kirkpatrick wrote. “Never mind what the landlord desires to do with her property. Under the act, the commercial tenant calls the shots.”

What Was the Original Intent?

Those in favor of the SBJSA say the measure is definitely not “commercial rent control,” including Ruth Messinger, the former City Council member and Democratic Party nominee for mayor. In 1986, when she represented the Council’s 4th District, Messinger wrote the initial version of the bill that has since been altered. She recently told The Bridge that, back then, “There was already an acute issue [with] small businesses establishing themselves, sometimes over three years, sometimes literally over 30 years, and all of a sudden running into the end of a lease at a point in which building owners felt—I think, largely correctly—that they could get much more for the space.”

Building owners asking for triple the rent on a new lease was one thing, but Messinger says a larger concern was the commonality of landlords only informing their tenants of a looming hike just prior to the lease’s expiration. “Because what they wanted was to get the existing tenant out in order to attract a new tenant,” Messinger says of landlords at the time. “I would say in most instances when the demand for a rent increase was huge, they knew that the tenant wouldn’t be able to pay, and they intensified that likelihood by telling them [shortly] before their lease was up.”

Rather than attempting to dictate rental rates, “it was a bill for binding arbitration in commercial-rent disputes,” Messinger says. “It required a back-and-forth negotiation [between the tenant and landlord], and maybe they would come to a meeting of the minds, but if they didn’t, they would go to an arbitration panel.”

Kirsten Theodos, a member of TakeBackNYC, a small-business advocacy group that has thrown its full support behind the SBJSA, and who recently wrote an op-ed for The Villager about the bill, worries that it could fall victim to mislabeling. “If it’s already being framed as something it’s not—‘commercial rent control,’” she told The Bridge last week, “it kind of makes you wonder, how fair is this hearing going to be?” Theodos argued that if the legal “nonsense” about the SBJSA is not refuted, the hearing will “revolve around the ‘legality’ of the bill, and we’re not going to have time to discuss real solutions.”

Whatever course the hearing takes, Eisenbach, who’s running for Public Advocate next year, believes that if the bill doesn’t pass through the City Council this year, it won’t get another chance for a long time, if ever. “I think this is the year. This is the window of opportunity and it really must be done now because we are losing so many businesses at an alarming rate,” Eisenbach said. “It’s really about the soul of the city. The loss of the small business is the loss of the character of our neighborhoods, the loss of the New York we all fell in love with.”