STEAM Rises: Brooklyn Students to Get a Tech Training Center

At the Navy Yard, high schoolers will get hands-on experience in the skilled professions of the future

The Navy Yard's Ehrenberg, left, schools chancellor Carranza and borough president Adams toured the construction site of the future STEAM Center (Photos by Steve Koepp)

Just as parents and policy makers have got on board the concept of STEM education (science, technology, engineering and math), along comes a new twist to the curriculum: STEAM, which adds art (and design) to the acronym. The good news is that Brooklyn won’t be playing catch-up, thanks to newly unveiled plans for the Brooklyn STEAM Center, a first-of-its-kind facility in the city where high-school students will get real-world, hands-on experience in the emerging professions of the future.

City officials, educators and students gathered Wednesday at the Brooklyn Navy Yard to unveil plans for the center, which will be housed in soon-to-be constructed facilities in Building 77, a World War II era behemoth that has been turned into a modern, light-industrial hub. When constructed, the center will serve 350 to 400 juniors and seniors drawn from eight Brooklyn public high schools.

The students will split their time between traditional studies and high-quality career and technical education (CTE), so that they’ll be well-prepared to go on to higher education or get right to work in jobs that require tech skills. “It’s important that students have a pathway to college and a profession, with an emphasis on the and,” said New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza.

Students currently enrolled in the STEAM Center’s pilot program

“It’s not the voc-ed of the past,” said Carranza, adding that his father was a journeyman sheet-metal worker, whose work showed Carranza the intersection between geometry and craftsmanship.

What’s unusual about the STEAM program is that it will be housed amid 100 companies and 3,000 workers, who will have a real-world influence on what the students learn. “I think it’s great that we’re in the middle of businesses. This will give them opportunities that they wouldn’t have otherwise,” said Summer Elsayed, who teaches construction in the pilot version of the program, currently housed in two Brooklyn high schools. “For me, being young and female shows them the opportunities they have ahead of them. They’re great kids. They deserve every possible opportunity.”

“They’ll be ready to work while they’re still students,” said professional chef and culinary instructor Shelly Flash on a tour of the future STEAM center

The STEAM Center’s curriculum will focus on five career pathways: culinary arts and business, design and engineering, construction technology, computer science and IT, and film and media. The space will be designed and equipped to look as much a possible like a place of business, said David Ehrenberg, CEO of the Navy Yard, which will supervise design and construction.

The center will benefit from $5 million in funding from Borough President Eric Adams, whose office has allocated more than $25 million in fiscal year 2019 toward science and tech education. His enthusiasm for “pipeline education,” he said, draws on his early experience as a police officer, when he saw that many young people who got into trouble shared one thing: a lack of opportunity. “Either we have a pipeline to prison or a pipeline to a profession,” he said.

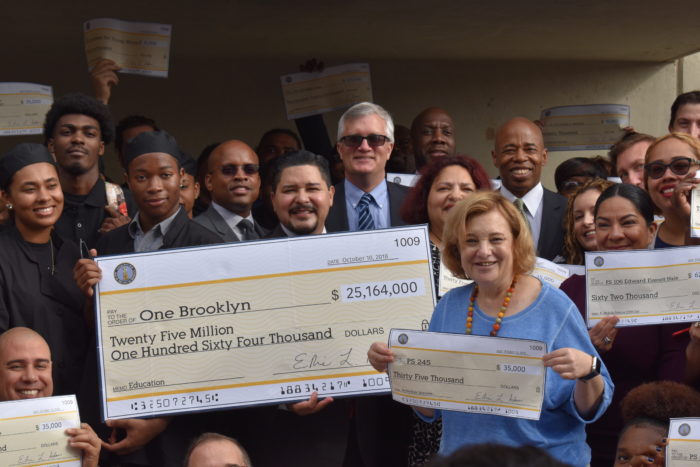

At the Navy Yard, city officials, educators and students celebrated the funding of the center

In a tour of the raw construction site, Kayon Pryce, the center’s founding principal, rattled off some of the technical specialties to be taught in the facilities, from robotics engineering to drone piloting. “We want to make sure we’re creating pathways to industries that have growth potential.” Pryce said the school’s leadership is working closing with industry experts on the space layout, equipment and curriculum for the program.

Ehrenberg said the Navy Yard’s role in the new center had its beginnings four years ago, when he and staff members were musing about how to satisfy the need for skilled workers, asking themselves, “How do we lead the future of workforce development?” Their answer came soon after in a cold call from Lester Young, a regent of the New York State Education Department and a former city-school superintendent, who suggested something much like what the Brooklyn STEAM Center will become. The ideas will keep on coming, Ehrenberg said, from an advisory committee of 50 entrepreneurs and other experts.