How Ample Hills Nails the Cultural Zeitgeist

You’re never going to find avocado ice cream at Ample Hills. They’re not churning bits of sage or prosciutto chips into their concoctions. And there’s definitely no coconut ash on the menu.

The Brooklyn-born ice cream shop isn’t doing what you might expect from a typical Brooklyn food pioneer–breaking experimental new flavors–and that’s entirely the point. “We do not make serious ice cream,” their site proclaims. But they are particularly skilled at telling fun, culturally relevant stories around an old-fashioned treat.

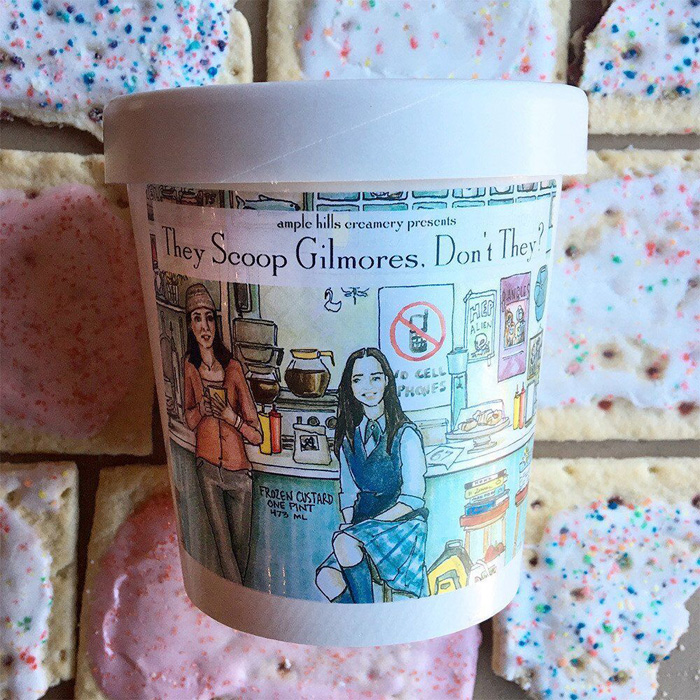

The opening of their first Prospect Heights outpost in 2011 is a story revered in the borough’s small-business world. They sold out of ice cream in four days, with adoration, glowing press and eventually even Oprah’s seal of approval. Since then, Ample Hills Creamery has used their nimble operation to create flavors around pop-culture darlings including Star Wars, Breaking Bad, The X-Files, Mad Men, and most recently, a Gilmore Girls-inspired flavor that gained attention in Vanity Fair, Eater and many other outlets. In January, they even created a flavor for The View’s 20th anniversary; the chocolate marshmallow ice cream, with house-made “Ooey Gooey” and “Salted Crack” cookies and fudge brownies, was meant to symbolize the talk show’s differing points of view.

The Gilmore Girls flavor was coffee chocolate-pudding with snickerdoodles and pink sprinkles

So what churns their imagination? It might be appropriate to call husband-and-wife co-owners Brian Smith and Jackie Cuscuna expert storytellers and marketers who just happen to own an ice-cream shop. “It’s relatively easy to get press for a new shop opening,” says Smith. “It’s very difficult to get press for opening your ninth or tenth ice cream shop.” Their solution? Tell new stories. In this case, a keen awareness of the zeitgeist seems to come naturally to Smith, who wrote sci-fi screenplays and produced radio plays before opening Ample Hills at age 40.

A Scoop of Inside Jokes

But there are some cultural touchstones that sneak up on him. Most recently, the Gilmore Girls flavor nearly didn’t happen. Ample Hills’ art director Lauren Kaelin, who’s responsible for the brands’ clever murals and pint-container designs, suggested the idea after noticing how much attention the food-and-drink obsessed series was getting in anticipation of its Netflix revival. “I had never seen Gilmore Girls,” says Smith. “I said, No, that sounds crazy, but then let her convince me and she was absolutely right.”

They put out a call on social media for Gilmore Girls flavors and names. Two thousand suggestions later, let’s just say fans of the fictional town of Stars Hollow, CT, are an enthusiastic bunch. The winner, an inside joke-heavy treat called They Scoop Gilmores, Don’t They?, is a coffee chocolate-pudding ice cream with snickerdoodles and pink sprinkles. It ended the year as the store’s most popular promotional flavor.

All that positive notice boosted foot traffic in their shops, expanded their reach on social media, and translated into a small boon in online orders which they ship nationwide packed in dry ice. Ample Hills is able to produce these flavors quickly because of the company’s relatively small size, but the business is growing. They now employ 90 to 100 workers (called Amployees) at five shops in New York City and one outpost at Disney in Orlando.

The limited-edition pints based on 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens came from an official partnership with Lucasfilm

The store’s first pop-culture foray was the Heisenberry, a sweet-cream concoction with raspberry preserves and blue Pop Rocks made to celebrate Breaking Bad‘s finale, complete with official prop candy from the show, which Ample Hills imported from Albuquerque. (Since they’re family-friendly, that flavor was available only for people who requested it—they didn’t want kids to get the wrong idea about the “blue stuff.” ) There was also One More for the Road, a Mad Men finale ode with Canadian Club whisky and glazed orange peel, and The Truth Is In Here, a paranormal green pistachio ice cream with chocolate-covered sunflower seeds for The X-Files’ long-awaited return.

Audience Participation

Smith considers these flavors to be like fan fiction, since customers are involved with creating and naming them. None of them are officially licensed except for limited-edition pints based on 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens. The flavors, dubbed The Light Side and The Dark Side, came from an official partnership with Lucas film. “Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney, is a fan of ours and reached out tome and offered to sort of mentor us,” says Smith. “I ended up pitching him on doing the Star Wars ice cream. For me, being a sci-fi movie writer and being obsessed with all things J.J. Abrams, getting to meet him, talk to him, and share ice cream with him, and make the Star Wars ice cream, that was the Holy Grail.”

One of Smith’s goals is to do a series of stories and ice cream flavors with famous writers, similar to Chipotle’s author-penned short stories on their takeout bags and cups. He’ll have to add that to other big projects on the horizon. Thanks to a $4 million equity round raised in 2015, led by Brooklyn Bridge Ventures, Ample Hills will open in late spring their largest endeavor yet: a 15,000-square-foot interactive destination in Red Hook with a retail shop, classes, self-guided tours, and plenty of room for ice-cream birthday parties.

Meanwhile, they’ll keep churning ice cream and telling stories. “Ice cream is like soup, you can do absolutely anything with it,” says Smith. “The possibilities are endless.”

Brooklyn’s Latest Small-batch Product: Electricity

What if your local bodega sold not only potato chips, six packs and toilet paper, but 14 kilowatts of solar-generated electricity? That’s the future think behind Park Slope-based LO3 Energy’s innovative project, Brooklyn Microgrid, which pioneers the idea of electricity as a home-grown commodity.

Not far from the aromatic Gowanus canal, in a Brooklyn neighborhood blossoming with hotels, a boutique ice-cream shop and a barbecue hall, LO3 Energy is rolling out its test case in a five-block by five-block power grid, which by midyear will include 40 electric meters that monitor current in two directions: coming and going. If the test goes well, they will take up more participants on a rolling basis. The first test, in April 2016, connecting two neighbors on President Street, proved out the basic concept and technology. The buying neighbor paid his solar-generating neighbor around $13 a month in credits for his excess power. Distributed electric grids are a growth technology right now. The benefits are many:

- Decentralizing power distribution for better security in case of a terror attack or weather emergency;

- Reducing the energy loss from sending current over long stretches of wire;

- Exploiting innovations in solar and wind energy that allow homeowners to produce power beyond their needs;

- Meeting the demand of growing cities so utility companies don’t need to build more expensive power plants.

The Brooklyn Microgrid, which is organized as a public-benefit company, was launched primarily to address that first need: safety. When Superstorm Sandy blasted the east coast in 2012, the Gowanus Canal flooded, knocking out power to businesses and residents for more than three weeks. That caused job layoffs in some blocks, and the 3,000 people living in the Gowanus housing projects suffered a devastating 11-day loss of power. Initially, LO3, a power-technology startup, signed on to construct a parallel grid system using ConEd’s utility wires. That way, if the traditional grid were knocked out, the neighborhood could change over to locally generated energy, primarily a combined heat-and-power system in the housing projects using natural gas to generate electricity and diverting the remaining power for heat.

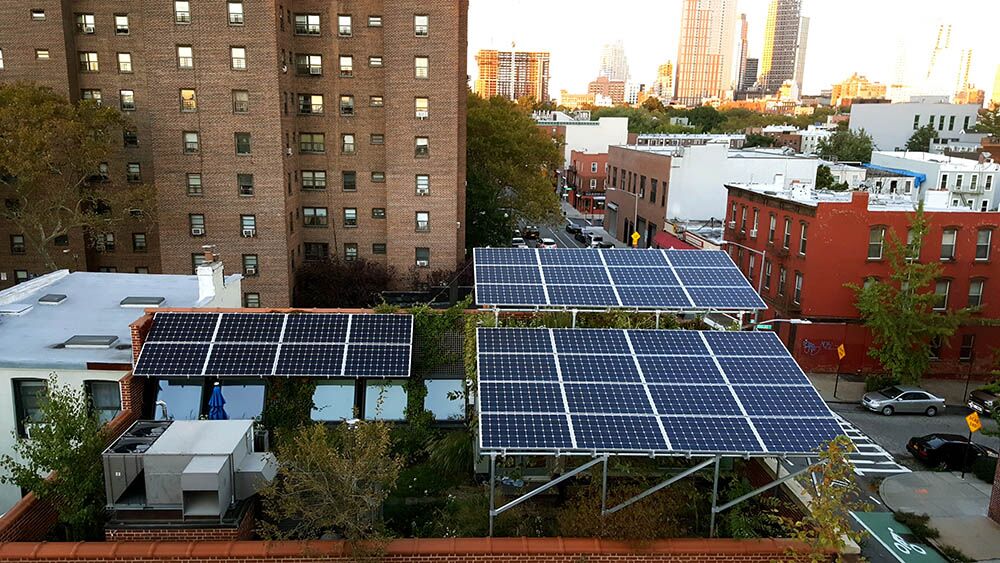

Solar panels atop houses in Gowanus provide electricity for neighbors when the owners have a surplus. (Photo credit: Sasha Santiago/LO3 Energy)

While embarking on that project, the LO3 team imagined other potentials for the microgrid, including locally sourced clean energy. When people buy into energy plans that seem to deliver wind- or solar-powered energy to their city homes through the large utilities, they are not literally receiving a direct stream of clean power but underwriting the construction of renewable generation upstate or even farther away. The concept is that all electron generation goes into the same pool, but the likelihood that a Brooklyn resident is getting an electron from a Syracuse renewable is slim, simply because the grid pulls from the closest source of energy. “People in the community who think they are getting green energy are really getting their electrons from a fossil-fuel based source. People don’t understand that,” says Scott Kessler, LO3’s director of operations. “One person even told us she was using more energy because she thought she was supporting the green initiative. We think there should be a direct local tie between what you are buying and what you are getting.”

Why a Microgrid in Gowanus?

The Gowanus area offers a particularly useful laboratory for energy solutions that LO3 hopes to apply around the world. Gowanus presents an intriguing socio-economic mix of residents; architectural diversity including small brownstones, large multifamily homes and industrial warehouses; and a strong environmental consciousness. Active early adopters include Whole Foods, which generates most of its own energy needs through a solar canopy, windmills and a combined heat-power unit. Kessler says Brooklyn has barely begun to tap its own potential riches. “New York has better solar potential than Germany,” he says, “and Germany has so much solar installed, at a certain point in the year, people were paid to consume it. It gets to a negative cost.”

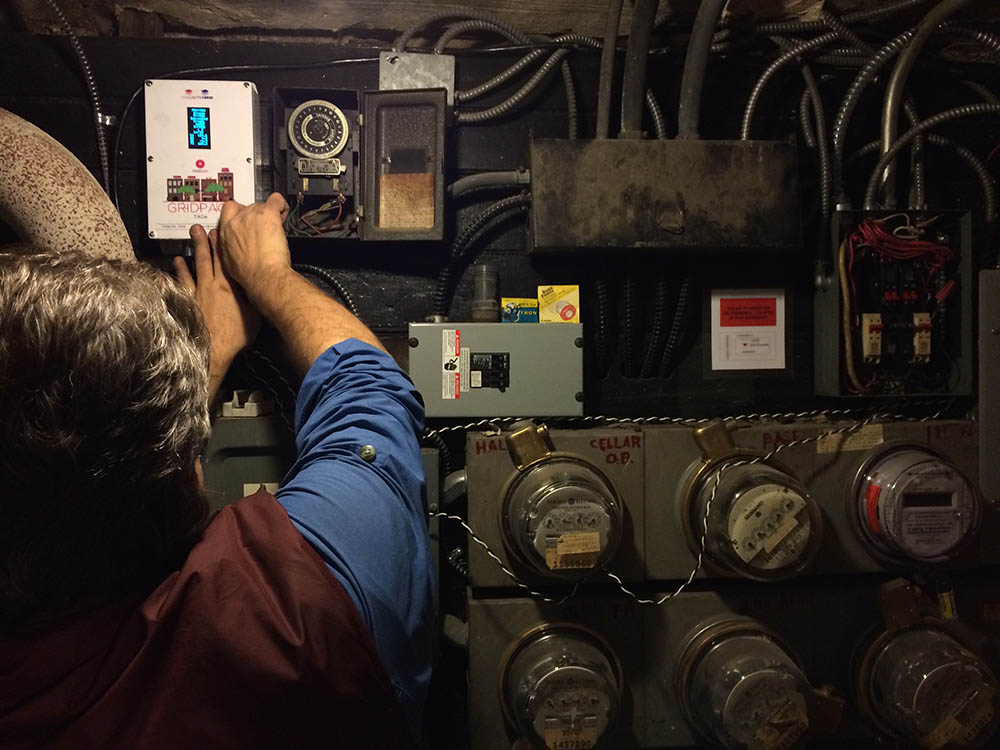

Joining the microgrid involves the installation of new meters that measure power traveling in two directions. (Photo credit: Sasha Santiago/ LO3 Energy)

So Brooklyn neighbors selling solar energy to one another should be a no brainer. But a few problems stand in the way. One, it’s illegal in New York State for people to privately sell energy; it must go through the utility. LO3 Energy answered that problem by designing an app called TransActive Grid, based on blockchain, the digital-ledger system that powers Bitcoin. The app allows grid participants to transform their energy into non-monetary units, set their top price for buying local power, and have it delivered whenever that price is right.

Let’s say a cloudy day reduces solar harvest and the demand outstrips normal supply. The price might rise. When it rises to a level that is beyond the consumer’s pre-set limits, the consumer would switch over to the standard carbon-based grid for consumption. If the microgrid creates an abundance of solar energy and the price is favorable, the consumer can have a home or business run entirely by neighborhood clean energy. The provider, meanwhile, would receive a credit from the utility company.

Scaling It Up

One might think that the big power utilities would resist the idea of home-grown power, but Kessler says they show real interest. “There are folks in the utilities business who are really into this. They think it’s the coolest thing in the world. They love solar and renewables. They just can’t figure out a way that it doesn’t put them out of business. And New York is trying to get ahead of that,” says Kessler. By state law, a large portion of a consumer’s electric bill is a fixed cost for maintenance of the overall system, protecting the utility from financial losses based on the ups and downs of energy consumption. One day, however, electric rates might be based on the distance from generation. So getting your power locally could theoretically lower your bill. That change is a long way off, but the dream is charging up along the Gowanus canal.