Why These New Headphones Are ‘Glasses for Your Ears’

A Brooklyn-based tech startup called Even is pioneering 'earprints,' which customize sound to a user's ears

The company's technology generates a personalized equalizer based on a user’s hearing strengths and weaknesses (Photos courtesy of Even)

A few years ago, when Bay Area entrepreneur Ofer Raz went on a trip to Best Buy for some headphones, he called for some advice from his friend Danny Aronson, a classically trained musician and sound engineer. But Aronson struggled to come up with a satisfactory answer, even though he says he had “tried all the headphones” on the market, from low-end to high-end. “I can actually read the specs,” Aronson says, referring to the descriptions of the products, “and know what’s in them. And there’s a lot of bullshit. A lot of bullshit.”

Aronson thinks most consumers tend to believe that the more expensive product is the better one, and many buy into the technical mumbo jumbo printed on the boxes even if they don’t really understand it. More importantly, unless the consumer has a trained ear, it would be hard to notice a difference between such products anyway.

“In general, I think we need to move audio forward,” Aronson says. “It’s such a hyped category and a very noisy category, with very little innovation.” The call from his friend got Aronson, now 47, to thinking about how his hearing capabilities had changed over the years, which is natural. That’s when the big idea hit him, that there’s a void in the headphone market because nobody had ever developed technology that caters to an individual’s hearing. “All these audio companies are completely ignoring the actual instrument you use to listen to music, which is your ears,” Aronson says. “The better you hear, the better music moves you.”

Even’s co-founder and CEO, Danny Aronson

So in 2014, Aronson and Raz co-founded Even, a Brooklyn-based tech company built atop their patented “Even EarPrint” software. After a 90-second diagnostic test, an algorithm generates a personalized equalizer based on a user’s hearing strengths and weaknesses. The program learns the frequencies where a listener needs reinforcement. Accompanied by an Even phone app, the company’s Bluetooth headphones also allow multiple earprints to be stored, since our hearing varies depending on the setting. Ever turn up the volume on your headphones as you head underground on the subway? With Even, you can instead click on another earprint made specifically for the train tunnel.

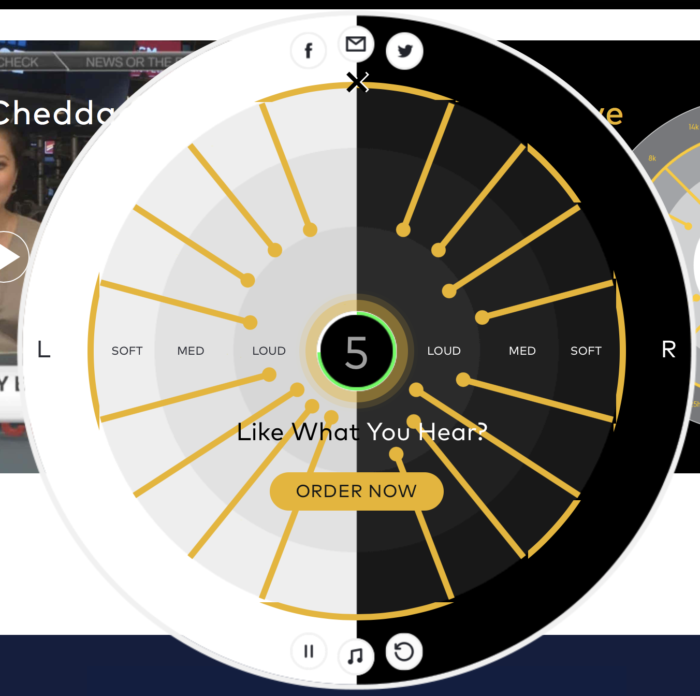

I tried the Even earprint test demo for myself at home. A lifelong music lover, and former live sound engineer, I presumed it would take quite a bit to impress me. I opened the demo on the Even website, where a circular graphic, broken up into halves (one side for each ear) is displayed. (Even’s earprint test can be executed on the headphones themselves as well.) A yellow ring within the circle is pockmarked with 16 dots, eight per side, representing each stage of the test in which the listener’s ability to register different frequencies is measured. Three thicker interior rings labeled “soft,” “med,” and “loud” are landing spots for measurements of how much compensation at eight different frequencies is required in each ear for the user.

When the demo starts, “Sarah,” a computerized guide, explains she’ll be taking your earprint. Users are instructed to click a button in the middle of the circle each time they begin to hear music, which are electronic tracks written and performed by Aronson himself.

The display of a self-administered test to create your own individualized “earprint”

I happen to live a half-block from an elevated train track and was concerned that it and other street-level noise would impact the test. They did, but that’s part of the point of the test: to quantify how one hears at any given time and in any setting. Less than two minutes later, I was ready to hear the results, a demonstration of music customized to my ears. Users can choose a 60-second stream of music from one of several genres, including soul, indie, rock, hip hop, jazz, and folk.

I chose rock, listening to the demo of ten seconds playing without my earprint enabled, and then ten seconds with it on. Even with my journalistic objectivity fully in mind, I have to say the difference was mind-blowing. Low-mid-range frequencies and bass boomed, just how I like it. (Not every user may hear such a profound effect, of course.) The experience took me back to my sound-engineering days, a decade and a half ago, where, in a club with two massive monitors and a 16-track mixer, I made every band sound as robust as I could.

Aronson says he had the same reaction when he first sampled his handiwork. “The first time I took the test, after a long time working on it,” he recalls, “I had to pick my brain up off the floor because I hadn’t heard music like that in literally 20 years.”

The company’s first products were earbuds, which sold briskly

A year and a half ago, Even manufactured a batch of ear buds embedded with their new earprint technology for market test, sometimes called a “POC” for “proof of concept.” Usually, expectations of a POC are that the company will log observations on how to improve their product. But Aronson says they sold out of the ear buds in 48 hours. They built more and sold another set within a week. “This POC actually became a source of revenue for the company,” Aronson says. “We sold, over the past year and a half, over $1 million worth of product, and we’re a tiny, tiny company doing hardware, which is challenging.”

Even now offers the earbuds (priced at $99), plus two types of headphones: H1 ($149) and a wireless model, H2 ($229), which can be ordered from the company’s website. By comparison, the priciest commercial pair by Beats is $400.

Aronson calls Even an “ambitious company.” He envisions its earprint technology as something that can turn up in smart TVs, live-music monitors, and any other listening device. He calls other headphone companies not “competition,” but “potential licensees,” as individualized hearing profiles become a common feature built into hardware. Venture capitalists have endorsed the company’s potential, investing $4.7 million to date.

With the business taking off and presenting a busy travel schedule, Aronson last year moved his family–he and his wife have three children–from his native Tel Aviv to Park Slope. “It was just a no-brainer that we’d come to New York,” Aronson says. “If you’re dealing with technology and music, I doubt there’s a better place to be. It’s the beating heart of the world, and Brooklyn just immediately felt like home. It’s such a vibrant place to be, and very accepting and multicultural, which is very important to me.”

Aronson believes that once consumers embrace the earprint concept, they’ll see the benefit, which the company pitches with the motto “Glasses for Your Ears.” Says Aronson: “I have a deep belief that technology’s place in our lives is to make life better, and to make quality-of-life improvements for people. We think we’re doing that.”