A Tale of Two Dwellings in the Flood Zone of Red Hook

A special report, part 3: Five years after Sandy, a luxury condo and a giant housing project have something in common–preparing for the next one

The new condo building 160 Imlay, a deluxe conversion of a dock building constructed in 1910, will have 70 units on six floors. Average list price: $1.7 million (Image courtesy of Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

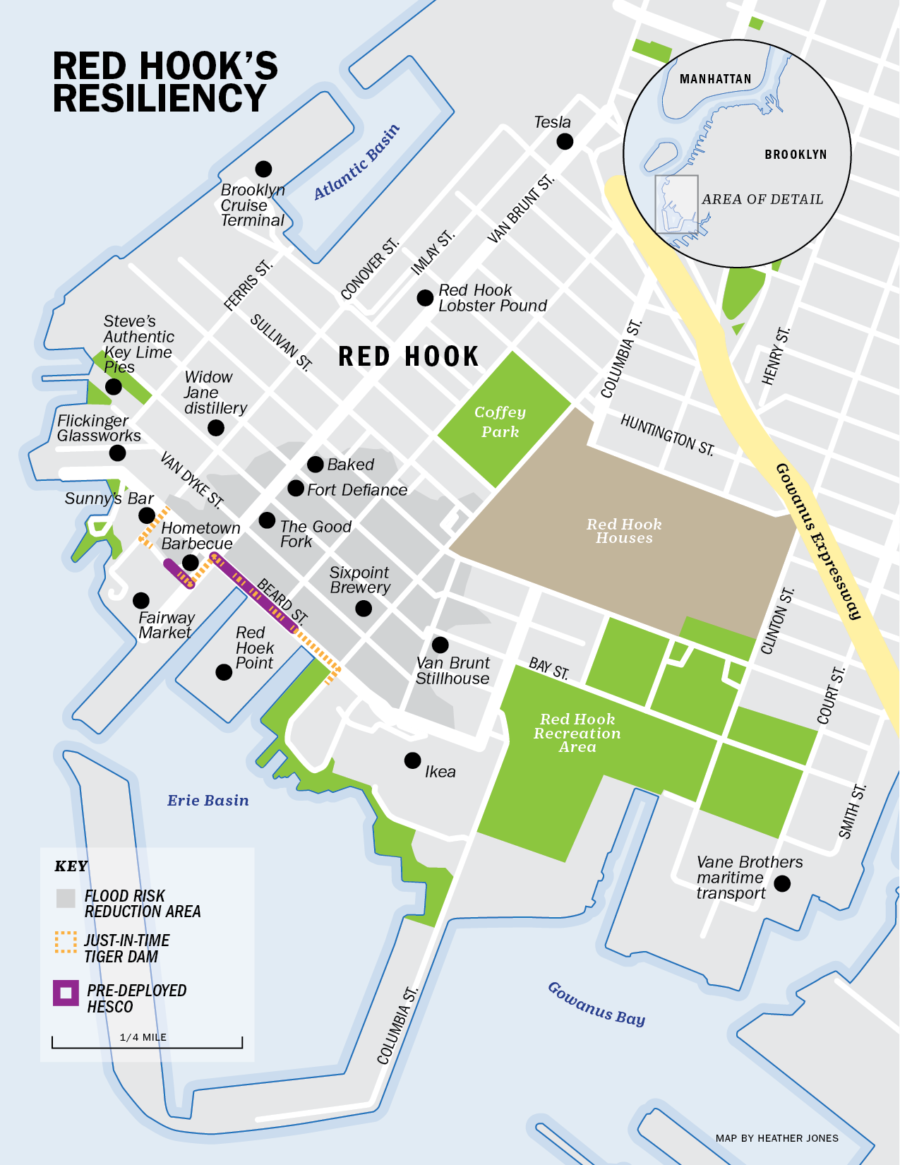

New York is a city where lofty wealth can live side by side with grueling poverty—and few neighborhoods illustrate that split personality better than Brooklyn’s Red Hook. Once the busiest freight port in the world, by the 1980s Red Hook was one of the poorest neighborhoods in the U.S., cut off from the rest of New York by the water that borders it on three sides, and by the Gowanus Expressway to the east. Yet while the 21st century has witnessed a Red Hook renaissance—with multi-million-dollar condo sales making Red Hook at least temporarily the priciest neighborhood in Brooklyn—the area still has a poverty rate of nearly 50%. More than half of the neighborhood’s population lives in the Red Hook Houses, the largest public housing project in Brooklyn and one of the oldest in New York.

In the aftermath of Sandy, residents of the Red Hook Houses were without power for weeks. Tameka Evans, with her two-year-old son, used her gas stove to keep the apartment warm (Photo by Gregory P. Mango/Polaris)

Those houses were hit hard by the flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Power was knocked out in most of the buildings for some three weeks—significantly longer than other parts of New York that lost power during Sandy—and running water was out for almost as long. Because storm damage to the New York City Housing Authority’s buildings was so widespread, the agency struggled to get utilities back online. The Red Hook Houses had no heat for weeks, including during nights when temperatures dipped into the 30s. Water damaged the roofs and walls of the buildings, leading to significant mold growth. Even after utilities were said to be restored to the Red Hook Houses, some residents reported intermittent failures for the rest of the year.

Part three of a three-part special report from The Bridge

The Red Hook Houses were hardly the only buildings in the neighborhood badly damaged by Sandy. Floodwater, after all, doesn’t take income into account–only elevation–and barely a block in low-lying Red Hook remained untouched after the storm. But walk around much of Red Hook today, and you might have little idea that Sandy ever happened. The neighborhood, long isolated from the rest of Brooklyn’s boom, has taken flight, with a fleet of new waterfront condo buildings and townhouses on the way.

Among them is 160 Imlay, where the Italian developer Estate Four has converted the decrepit New York Dock Co. building into what will be some of the most expensive condos in the neighborhood. The development is the convergence of old and new Red Hook—a long-abandoned waterfront building that dates to Red Hook’s glory days as a major freight port, now transformed into luxury residences for buyers willing to spend in the seven figures. What those two Red Hooks have in common is water. 160 Imlay faces the Atlantic Basin, a man-made harborage that once hosted ships by the hundreds. In Red Hook’s port days, that location mattered for its proximity to the water as a highway. Today its value is in water views for condo residents.

The Red Hook Houses are the largest public-housing project in Brooklyn, with about 6,000 residents (Photo by Timothy Fadek)

The Red Hook Houses, while set back from the shoreline, have roots in the neighborhood’s maritime past as well—the buildings were first constructed in the 1930s for the families of Red Hook dockworkers. But today the water is something to be defended from. And in the years since Sandy struck, New York has taken steps to strengthen the Red Hook Houses and other vulnerable public housing projects from future floods. (Ten percent of New York’s public-housing projects and more than 80,000 residents were affected by Sandy, causing over $3 billion in damage.)

As part of a nearly $3 billion grant from the Federal Emergency Management Authority—the biggest in the agency’s history—last month September the city Housing Authority broke ground on a $63 million project to replace all 28 roofs at the Red Hook Houses. Eventually the city agency will spend almost $550 million in total to harden the buildings against future floods, including installing electrical rooms and boilers above the level of a 100-year-flood, as well as putting in backup generators. “By 2021, we’ll be leaving this site stronger and more prepared for future storms,” promised Shola Olatoye, the Housing Authority CEO, in kicking off the roof-repair phase of the project.

The view across Buttermilk Channel from a condo at 160 Imlay (Image courtesy of Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Sandy’s damage to the Red Hook Houses and to other public-housing projects was so severe not just because of their location, but because much of the city’s public-housing stock was rundown well before the flood. While the Red Hook Houses will come out of the Sandy rebuild tougher and more resilient than they were before, how many times can New York—or any city—afford to embark on multibillion-dollar reconstruction? It’s hard enough to keep public housing running on sunny days. What will happen if, as some studies predict, Sandy-level catastrophes begin hitting New York as often as every five years?

The well-heeled residents of new Red Hook developments like 160 Imlay might wonder too. The architects behind the project have said they’ve taken Sandy and future flooding into account, raising mechanical and electrical equipment above the flood level, filling in the basement—particularly important because of Red Hook’s shallow groundwater—and flood proofing other vulnerable areas, including the water-heating system. That’s partially the advantage of new construction—the city mandates that new or significantly renovated construction take flood hazards into consideration.

Their waterfront location may seem vulnerable, but post-Sandy buildings like 160 Imlay will be in a better position than some others to weather the next storm. “The water can come sloshing through the building, and the electrical equipment will be fine,” says Patty LaRocco, an agent at Douglas Elliman Real Estate and the broker for 160 Imlay. “It’s 18 feet above sea level.” She also notes that the development will benefit from a FEMA-funded flood wall that is planned for the Atlantic Basin. “This building will be the last building standing if anything happens.”

What’s happening at the Red Hook Houses and at 160 Imlay demonstrates that there are practical steps that can be taken to protect New York property—at the poorest level and at the richest—from more frequent and devastating floods. It won’t keep the neighborhood safe forever, not with climate change raising sea levels by feet in the decades to come, not when all of Red Hook could end up submerged someday. But it’s a start, as Red Hook’s relationship to the water changes once again.

Make an aerial visit to Red Hook via our drone-powered tour of the neighborhood