How a Rising Brooklyn Hospital Aims to Upgrade Health Care

After a merger, Park Slope's neighborhood institution is growing in scale and expertise. PLUS: our ranking of Brooklyn's 15 largest hospitals

The Center for Community Health, focused on ambulatory care, is scheduled to open in April 2020 (Rendering by Perkins Eastman)

In low-rise Park Slope, the two gigantic cranes towering over the construction site at Sixth Street and Eighth Avenue signal the arrival of something big. Physically, the cranes foreshadow the coming of the 400,000-sq.-ft. Center for Community Health. Set to open in April 2020, the huge new CCH will be an ambulatory-care center focusing on outpatient surgery. Symbolically, the construction site heralds something more: a world-class hospital rising up in the neighborhood.

In late 2016, Park Slope’s neighborhood hospital, Methodist, quietly merged with Manhattan’s elite NewYork-Presbyterian to become the long-winded NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital. While locals can be forgiven for continuing to call it “Methodist” for short, its reputation is growing along with its name as the Park Slope hospital adds specialists and access to the larger Presbyterian network. Brooklyn used to be served mostly by neighborhood hospitals of varying quality, but the consolidation in the industry has brought giant Manhattan institutions into the borough, drawn by the borough’s growing population and prosperity.

“The mission is not to act as a feeder to NewYork-Presbyterian in Manhattan,” the Park Slope hospital’s president, Dr. Richard Liebowitz, told The Bridge. “The idea was to attract patients here. The only reason to send patients into Manhattan is for those things that we don’t do here, so it’s really to build and strengthen the hospital in Brooklyn.”

The two cranes tower over Park Slope’s low-rise brownstones (Photo by Hannah Frishberg)

Unlike other Brooklyn hospital mergers, this is not a full-assets merger: it is an “active parent merger,” meaning Methodist and Presbyterian still maintain virtually separate boards of directors and administrations. “We really are administratively run as two different hospitals with the linkage up to the system as whole,” Liebowitz said. In other words, Park Slopers get to keep their local hospital, which was founded in 1881, and have Manhattan quality too. The Presbyterian name and resources now boost Methodist to a higher standard and, in this instance, without the loss of jobs.

Since the merger, the 591-bed teaching hospital has added more than 250 registered nurses to its staff, as well as new physicians with such specialties as gastrointestinal cancers, liquid tumors, and robotic surgery for hernia repair. A stepdown unit has been added for heart-surgery patients, providing a place for those ready to leave the intensive-care unit but not ready for a regular floor, as well as a playroom for pediatric patients.

Most significantly in the works is the new CCH, which will offer facilities for cancer care as well as endoscopies and orthopedic surgery, with plans to treat 100,000 patients a year. While its purpose is not controversial, its placement has been the source of local resentment, since the structure required the demolition of 16 hospital-owned buildings which included a number of historic brownstones. The city awarded Methodist a special zoning variance for the facility’s development in 2014, before the formal merger. In response to neighborhood pushback about its size, the hospital reduced its height to six stories, from seven, and made other modifications.

Dr. Richard Liebowitz, president of the Park Slope hospital (Photo courtesy of NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital)

The local hospital merger is part of a growing national trend of consolidation, since the country has too many hospitals. Since 1981, the peak year for hospitalizations in the U.S., the number of hospitals has shrunk, to 5,534 this year, down from 6,933. The growth of efficient alternatives for ambulatory surgery and urgent care have hastened the trend. “Hospitals will start to evolve into large intensive-care units, where you go to get highly specialized, highly technical or serious critical care,” Bruce Leff, a geriatrician and professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told the Wall Street Journal.

The shakeout has produced neighborhood casualties, notably Cobble Hill’s money-losing Long Island College Hospital, whose campus was sold to developers who are now building a residential complex, leaving only a freestanding emergency center run by NYU Langone. As local hospitals consolidate into huge systems, some health-care experts see a potential downside. “They say that this will generate cost savings that can be passed along to patients, but in fact, the opposite happens. The mergers create local monopolies that raise prices to counter the decreased revenue from fewer occupied beds,” wrote Ezekiel Emanuel, a doctor and health-care investor, in the New York Times.

That said, neighborhood health-care providers welcome the Park Slope hospital’s upgrade. “If we’re going to have a community hospital in our neighborhood, it matters that it’s connected to an internationally recognized institution, and there’s no downsides to the neighborhood as far as I can tell,” said Dr. Dara Kass, a Park Slope resident, NYU emergency-medicine specialist, and founder of FemInEm, a resource for women working in emergency medicine.

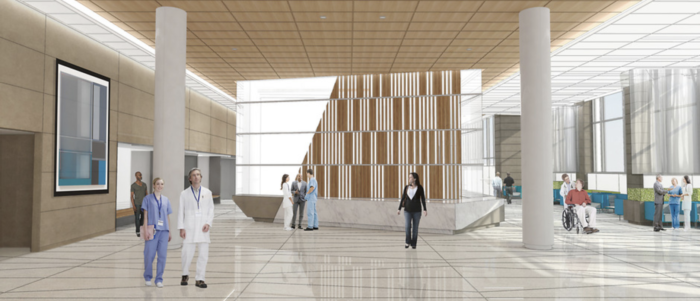

An interior view of the Center for Community Health, now under construction (Rendering by Perkins Eastman)

Being internally connected to Presbyterian, Kass explained, means that patients are “in the system from the very beginning,” and have access to Presbyterian’s much larger, robust system. “Now you have the Manhattan institutions supporting the Brooklyn institutions, so there’s a better conduit,” she said. Last year’s consolidation between Sunset Park’s Lutheran and NYU Langone reaped similar benefits, notably the Brooklyn hospital’s commitment to lead the borough in maternity care. Liebowitz says the Park Slope hospital, for its part, aspires to be No. 1 in cancer and cardiovascular care, as well as women’s health and pediatrics. “The thing that makes me really happy about these consolidations is it means people who can’t afford to see VIPs [doctors] at Columbia and Cornell and NYU get the same access to care at community hospitals,” Kass said.

As the Manhattan and Brooklyn institutions have merged, there has been at least one notable bit of culture shock: Brooklyn is no longer a residential backwater–or bargain. “As I brought over some people who worked at Presbyterian’s Manhattan side, they lived on the Upper East Side,” Liebowitz said. “Now, the problem is that housing in Park Slope is more expensive than the UES. Economically, it’s a bit of a challenge,” said Liebowitz, who was raised in Bensonhurst and is far from shocked by this reality. “That’s the history of New York, right?”

As Brooklyn’s health-care industry rapidly evolves, we compiled this list of borough hospitals with our partner Legendary Data, ranking the hospitals by their bed count and providing other data. If you see any errors or omissions, please let us know at editor@thebridgebk.com and we’ll make a prompt update.