How to Get a Liquor License in Brooklyn Without a Fight

The process can be daunting, often fraught with NIMBY neighbors. Here's how savvy entrepreneurs play the game

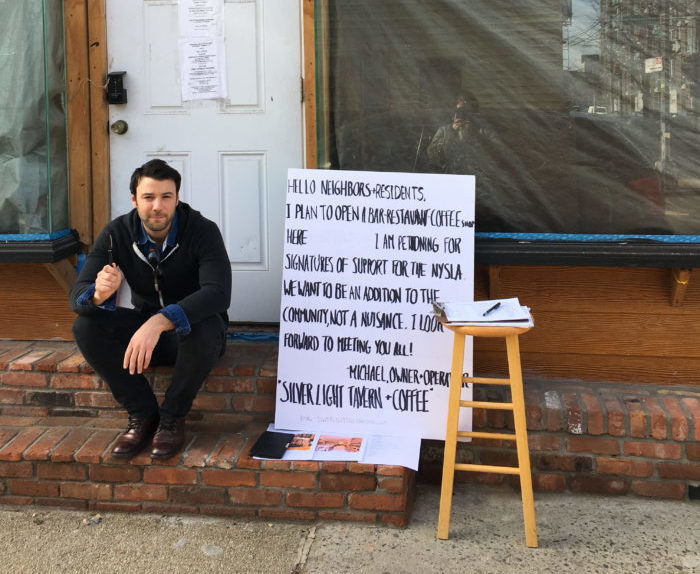

Prospective bar owner Michael Krawiec gathering signatures from neighbors at the site of his planned bar and coffeehouse (Photo courtesy of Michael Krawiec)

When Michael Krawiec discovered two adjoining, vacant storefronts on a corner in North Williamsburg during a space-scouting stroll a few months ago, he was gleeful. The entrepreneur was convinced he’d found the perfect landing spot for his next venture. “I didn’t think I’d be lucky enough to find a space like that,” says Krawiec.

Not only were the windowed, ground-floor commercial spaces set in a Brooklyn neighborhood teeming with high-profile new developments, including the William Vale Hotel and the under-construction 25 Kent office building, but they could seamlessly house his freshly hatched concept: a bar and a coffeehouse under one roof.

However, after coming to an agreement on rent with the building’s owner, Krawiec, a former co-owner of two bars in Astoria, his moment of triumph turned to anxiety when he considered the next hurdle: getting a liquor license for the place. Without that, there would be no economically viable new business, no matter how great the location.

One major hurdle for prospective bar owners is the 500-foot rule, which means that a community gives extra scrutiny to a proposed establishment that would be near other ones (Photo by Bitterfly/iStock by Getty Images)

Krawiec was aware that, before applying for the liquor license with the New York State Liquor Authority, he’d first have to plead his case to Brooklyn Community Board No. 1, or CB#1, which covers Williamsburg and Greenpoint. “I knew that CB#1 is very tough; they’re very thorough, very aware of what’s going in their neighborhood,” Krawiec says. “So I knew it was going to be a challenge.”

By and large, the explosive growth of Brooklyn’s nightlife scene into one of the best in the world has been a boon for borough residents and visitors. More than 600 bars opened in Brooklyn between 2011 and 2014 alone, while the overall tourism-and-entertainment has seen the best annual job-growth rate of any sector across the borough. It’s now the third-largest industry in Brooklyn, accounting for 53,900 jobs.

Yet the vitality of Brooklyn nightlife, already threatened by rising real-estate prices, could face another challenge: mounting pushback from community boards wary of allowing bar districts to disrupt residential areas. In Downtown Manhattan, the battle has already broken out in heated community meetings. Prospective bar owners have grown concerned that community boards in the city have already wielded too much power, making the procurement of liquor licenses too difficult for new business owners, who face a months-long process in obtaining one. To help such entrepreneurs with the many regulatory issues they face, Mayor de Blasio recently appointed the first “director of nightlife.”

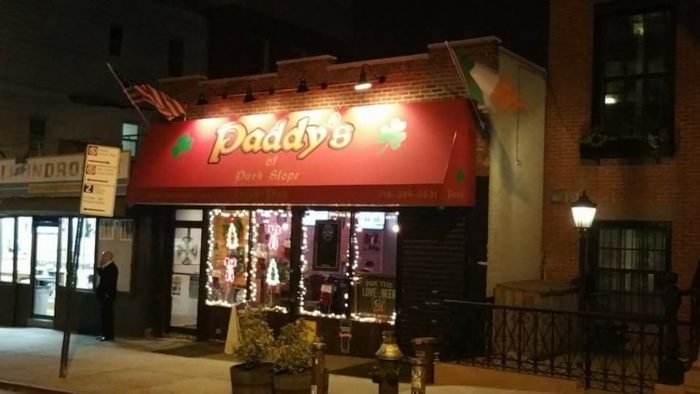

Paddy’s in Park Slope, which faced early challenges in getting a liquor license because of the reputation of the previous business at the location (Photo courtesy of Mark Langton)

The role of community boards in the process is to give the state liquor authority (SLA) their suggestions of approval or disapproval when a business owner wants to sell alcohol in their neighborhoods. The procedure is more formal, including a hearing, when the proposed business will be within a 500-foot radius of at least three other such premises. This law, known as “the 500-foot rule,” dates back to 1993, when a Queens State Senator drafted it in reaction to a shooting death of an off-duty police officer on a bar-rich boulevard in Bayside.

The 500-foot rule has created a treacherous hurdle for entrepreneurs, according to Robert Bookman, a lawyer for the New York City Hospitality Alliance, who has been representing bar, restaurant and club owners for 30 years. The law puts the burden on applicants to prove to community boards that their business is in the “public interest.” Says Bookman: “Of course the legislation did not define what ‘public interest’ means,” observing that its definition has had “a kind of ad hoc development over the years” within the SLA and community boards.

“The law intended communities to have input here, but it didn’t intend for them to have veto power,” Bookman continues. “Ostensibly that’s where we’re at now, though.”

In Krawiec’s case, to establish good standing with CB#1, which he stresses he has no ill feelings toward, the entrepreneur got creative. He drew up a sign announcing his intention to open Silver Light Tavern + Coffee on the coveted North Williamsburg corner and stood in front of the space talking to neighbors about his plans over ten winter days, in stints of six or eight hours a day.

“I didn’t want to be intrusive,” Krawiec says. “I didn’t want to go knocking on doors; I didn’t want to run up to people on the street.” Each time he spoke to a resident who expressed support, Krawiec asked for a petition signature, and says he ultimately garnered about 250. Many were struck by his congenial form of outreach. “A lot of people asked, ‘Is this normal?’” Krawiec recalls. “And I was like, ‘I don’t think so.’”

In other cases, the prospective bar owner can be haunted by the behavior of the previous proprietor. When Mark Langton looked to open Paddy’s Irish pub with his wife in Park Slope in 2015, he too knew he’d face an uphill climb in getting a liquor license. “The previous tenants had been here for 13 years,” Langton says, referring to the Paddy’s address. “It was a biker/strip bar, like there was literally a pole on the bar when we took it over.” Heavy-metal bands used to play in the space late into the evening.

Tips & Takeaways

Tips & Takeaways

- Hire an attorney or consultant to handle paperwork: They know the requirements and laws far better than you do. Any mistake on the application could cost you months in refiling efforts.

- Play nice with the community board: Chances are you’ll have to show them “public interest” in your bar. Be friendly to your new neighbors and seek their support. The community board can ultimately be your champion. At the very least, you’d prefer to have them as an ally rather than an enemy, so don’t look to be combative from the start.

- Work new-business-friendly clauses into your lease: At best, your liquor license will arrive in 90 days. See if your landlord will forego rent for a few months while you get the bar operational. Always have an “out” in the contract in case your liquor license is denied.

“From my point of view, as a human being and as a resident, I’d be of the same mind,” says Langton, who’d also co-owned a bar in Manhattan. “When it came time for us to look for our license, they objected.”

At the hearing with Community Board No. 6 when his application was considered, Langton says with a slight chuckle, “All hell broke loose.” Residents complained about anarchy at the location for years, but in such a way that seemed to lump Langton in with the prior owners. “I shouldn’t have, but I lost my temper,” he admits. “I said, ‘I don’t know who the hell you think you are, but we are not the people that you’re portraying.’”

Cooler heads eventually prevailed. A member of the community board observed that, in spite of residents’ displeasure with the bar’s former owners, their liquor license had always remained intact. Langton presented proof that there had never been a complaint filed with police against his bar in Manhattan and announced there’d be no live music at Paddy’s. He also got the email addresses of attendees at the meeting and offered to show them the renovations he was paying for that would improve the atmosphere of the bar.

Langton earned a liquor license that allows Paddy’s to stay open until 4 a.m., something that’s become a rarity in the city, according to both hospitality lawyer Bookman and Langton’s consultant, Anthony Caraballo, who’s been helping entrepreneurs with their liquor license filings for 15 years. “Mark did a great job at abating their concerns,” Caraballo says. “He’s a poster boy in my office in terms of the right way to go about dealing with opposition.” In a gesture of good faith to the neighborhood, Langton decided to close Paddy’s at 2 a.m. on Sundays through Wednesdays. He says he’s had no issues with CB#6 since, and has felt welcome and supported in Park Slope.

“I don’t think the liquor [license] application process itself is that overly cumbersome,” Bookman says, adding that the SLA has “done a good job of streamlining it.” But over the course of the past two decades, both Bookman and Caraballo insist community boards have become too strict and closed-minded at times. “It’s natural for residents to have concerns,” Caraballo says. “The community needs to be a part of this process, [but] I’ll qualify that statement by saying the opposition has to be credible. The opposition can’t just be of the nature that ‘we just don’t want a bar on our block.’”

Even if a new bar owner obtains community board approval for a liquor license, the entire application process takes about three months. That’s a long period of time to be paying rent on a commercial space with no guarantee the bar will ever become operational. If a community board recommends that the SLA should deny a license, one can still be awarded, but only after additional hearings and paperwork, which takes at least a couple more months.

Bookman advises prospective bar owners to seek a clause within their lease that allows them to nullify the agreement if a liquor license is denied, something Krawiec says he negotiated into his lease. Still, that type of arrangement requires a leap of faith on the part of building owners as well.

Once a bar owner gets a state license, the hurdles continue. The license renewal costs $5,000 every two years, no matter the bar’s volume; visits from the Health Department arrive without warning and can lead to unanticipated fines; the state imposes various taxes on top of New York State and City income taxes.

For any bar or restaurant to be a success in New York City, pretty much everything has to go right, given the costs and regulations. “If anybody tells you that they’re going to make money in the bar business … it’s not gonna happen,” Langton says, only slightly joking. “For little mom-and-pop stores like [Paddy’s], we literally bought ourselves a job.” Yet he’s happy to be a bar owner, given other benefits: the freedom to set work hours for himself, as well as engaging with scores of people in building a mini-community of his own.

Krawiec, in recounting his choice to stand outside his proposed establishment and talk with potential new neighbors, says, “I like people. That’s the whole reason I’m in the industry anyway.”

Krawiec’s affinity for interaction paid off. At a hearing in late February, during which Krawiec presented his signatures, Community Board No. 1 told him they’d suggest approval for his liquor license to the SLA, allowing Silver Light Tavern + Coffee to operate nightly until 2 a.m. once it’s open for business. Krawiec hopes that’ll happen sometime this fall.