How Music Became Big Business in Brooklyn

Next week's opening of the mammoth club Brooklyn Steel affirms the borough's status as a national music capital

The Bowery Presents principals Jim Glancy, left, and John Moore at the main bar of Brooklyn Steel, the new music concert venue in Williamsburg (Photo by Joshua Bright/The New York Times/Redux)

Until now, Brooklynites who’ve wanted to see a famous indie band often had to cross the river (ugh!) to catch a show at a big Manhattan club like Webster Hall or Irving Plaza.

That changes next week, when Brooklyn-born LCD Soundsystem takes up residence for five nights starting April 6 at a brand new venue, Brooklyn Steel, a 1,800-person club on the eastern side of Williamsburg. (Tickets go on sale today.) Music, one of the borough’s biggest exports, is staying home for a change.

“This is a recognition of how important Brooklyn has become to the music industry,” said Jim Glancy of The Bowery Presents, the New York City concert company behind Brooklyn Steel. “Ten years ago, you couldn’t get bookers for the bands to think about coming to Brooklyn. They would never consider [it].” The Williamsburg club is the latest big project for the company, whose venues include the Music Hall of Williamsburg, Terminal 5 in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood and other locations in Boston and Philadelphia.

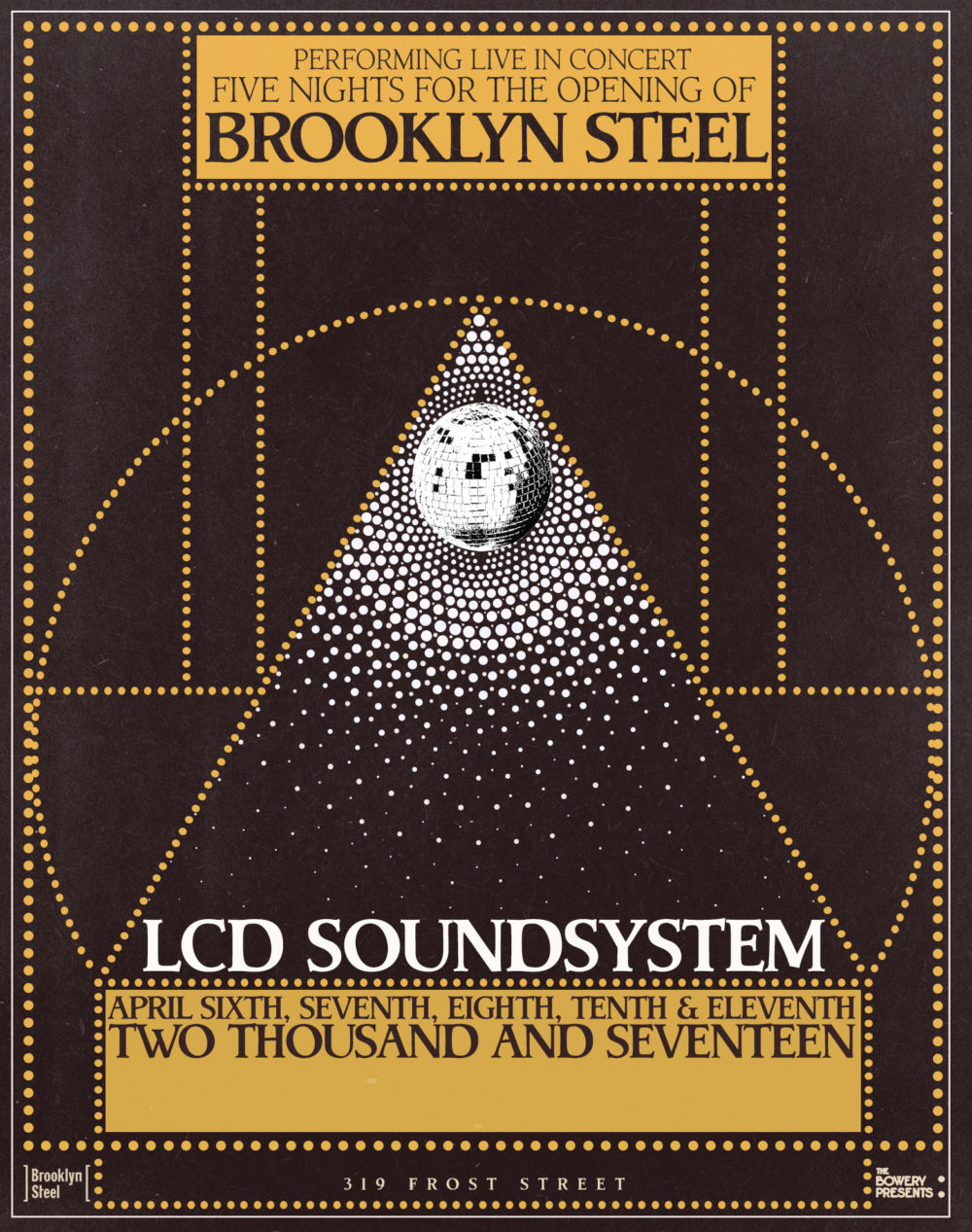

A poster for the opening act at the new Brooklyn venue

Brooklyn Steel lives up to its industrial roots, using materials repurposed from the old metal-fabrication shop it once was. The cavernous space is 20,000 sq. ft., with three bars, abundant restrooms, good sightlines and acoustics. “The layout is fairly simple,” Glancy said. “There are no doglegs or nooks and crannies.” The main lobby bar, created from scrap metal, features three large old ventilating fans and the building’s original window frames. An external courtyard allows customers to get off the street as they wait in line to get in.

The building, at 319 Frost St., was still a working industrial shop, Eliou and Scopelitis Steel Fabrication, when Glancy and his partners first visited the neighborhood looking for a club site. He said they were wowed by the space and its proximity to what they considered to be the music-fan base of Brooklyn. “We had looked all over and saw some great places,” Glancy said.

The company worked closely with Community Board 1 during planning and construction, pledging to become part of the neighborhood, a mix of homes and warehouses. Glancy’s company installed a “green” roof, similar to the one at Barclays Center, to help absorb noise. The company estimates the club will employ 50 to 60 people when it’s in operation.

A Thriving Industry

In New York City, music is very big business. An economic impact report released earlier this month by the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment estimates that the music industry provides 60,000 jobs and $5 billion in wages, with a total economic impact of $21 billion.

Blaming the high cost of real estate in Manhattan, however, the report found New York lagging behind London and San Francisco in the number of tickets to live music sold to 18-to-54 year olds. “To put it simply, adding more marquee venues in New York City would not cannibalize existing ticket sales, but help to grow the market–and satisfy the city’s high demand for live music,” the report said.

The music scene in Brooklyn has exploded since the Music Hall of Williamsburg opened as Northsix in 2001. While the borough was already dotted with small clubs, the 550-capacity venue cranked up the volume considerably. By the time Brooklyn Bowl opened in 2009, six blocks from the Music Hall, the scene was established and Williamsburg was filled with young residents who took music very seriously.

The club was still a working steel-fabricating plant when the new proprietors were scouting for locations (Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Steel)

The Bowery Presents saw the change in population when it did zip-code studies at its Brooklyn clubs. They found the opposite of the bridge-and-tunnel crowd, who haunted Manhattan by night and returned home to the sleepy outer boroughs. The audience for many bands has long moved to neighborhoods across Brooklyn, where they have also found employment and little reason to go back across the river. At the same time, the rise of rideshare services like Uber means that a club doesn’t necessarily have to be situated near convenient public transportation or parking space.

“It’s a different vibe in Brooklyn,” said Ron Roy, one of the founders of digital fan club Ultrastar, whose investors included David Bowie. “When you say you’re going to a show in Brooklyn, there’s different expectations than going to a club in Manhattan. It’s where the musicians live now and it has that community feel. You have a sense that you’re going to see something special, something you don’t get in Manhattan anymore.”

The Allure of Larger Venues

Musicians too have a stake in the proliferation of larger venues. As revenue from recording has ebbed, more bands have turned to touring to build fan bases, making halls the size of Brooklyn Steel in increasing demand throughout the U.S. Sports arenas like the Barclays Center can be filled by only a rarified few acts, while clubs like the Knitting Factory in Williamsburg are too small for more popular acts in a city the size of New York. The beautifully restored Kings Theatre in Flatbush can accommodate 3,000, but that’s a more formal, sit-down venue.

James Murphy, front man for LCD Soundsystem, will open the new venue with a five-night residency (Photo by Ruvan Wijesooriya)

For Brooklyn Steel, the opening month is a busy one, with shows by The New Decemberists and PJ Harvey. The announced schedule, fittingly diverse among avant garde, indie rock and folk rock, is nearly packed until mid June, with more shows to be announced.

Musicians may find the place as comfortable as the customers do. Glancy takes obvious pride in pointing out some of the amenities for performers, including fully equipped bathrooms and laundry facilities. It’s a long way from the primitive setting of the Manhattan clubs of yore, where restrooms were not for the faint of heart. Says Glancy: “We’re very happy with what we’ve built.”