How a Huge New Project Will Change the Face of Dumbo

The little-known history of 85 Jay: from Al Capone's school to Jehovah's Witnesses, a proposed arena, a Kushner role, and finally a 737-apartment giant

The planned complex at center, with two towers, will house 737 apartments (Photo-illustration courtesy of CityRealty)

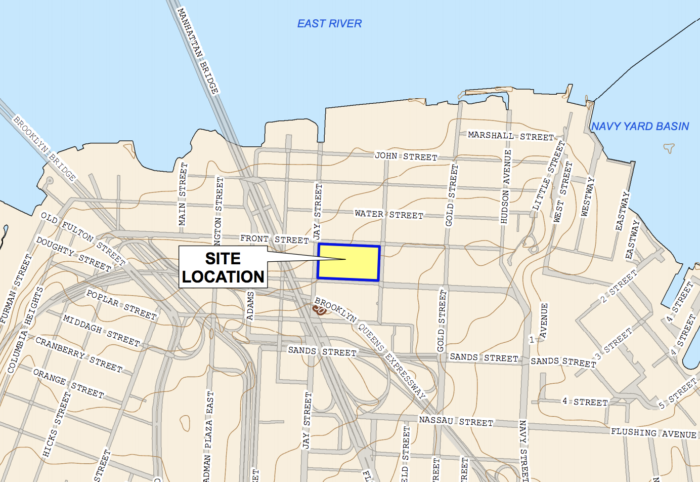

It has been called Dumbo’s “game-changing” project, a huge residential complex called 85 Jay, on a long-fallow, three-acre site at a key location bounded by York, Front, Jay, and Bridge streets.

It’ll have big impact: the complex could boost Dumbo’s population by 25%, adding street life, retail, connectivity, and buzz to an already hot neighborhood–plus putting strain on some antiquated infrastructure.

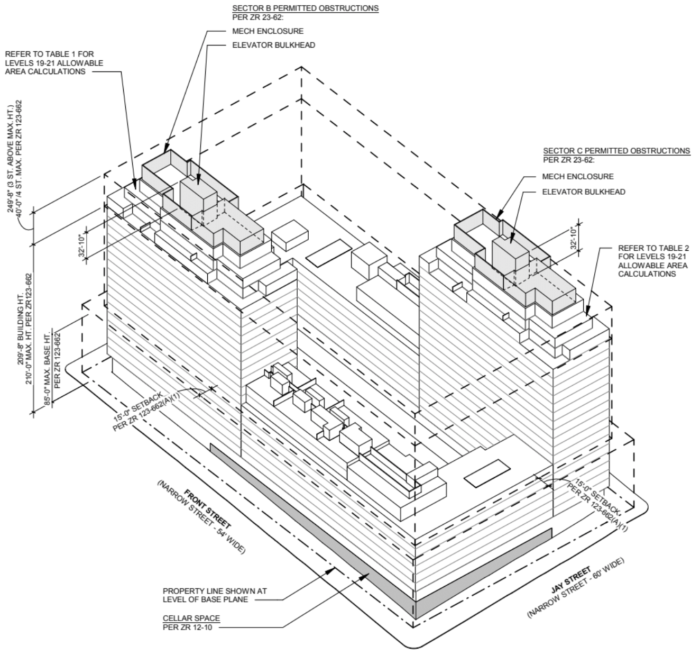

It’ll be imposing: 85 Jay will rise 250 feet, or 21 stories, at two corners, with lower segments at the opposite corners. With 874,000 sq. ft. of floor space, it will house 737 apartments, both rentals and condos, a good number of them likely family-sized, plus significant commercial space.

Work has been underway for several weeks at the site, seen here from the Manhattan Bridge (Photo by Steve Koepp)

It’s a big financial deal: in a $345 million transaction in 2016, a joint venture of CIM Group, Kushner, and Dumbo-based LIVWRK bought the parcel from the Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, otherwise known as the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Recently the small stake owned by the family of Jared Kushner, President Trump’s son-in-law, was bought out by the low-key CIM group. The total project cost is estimated at $1.1 billion.

It’s not much discussed: while plywood fencing is up, with clanking site work underway behind it, 85 Jay has flown somewhat under the radar. Because no rezoning or special approvals were needed for construction, it has avoided the public negotiations that often accompany large projects, involving pledges of union labor, affordable housing, or cuts in parking accommodations.

But 85 Jay still raises significant intrigue. With site work underway–completion is slated for summer 2021–and its real-estate sales office to open soon at 10 Jay St. on the waterfront, we decided to take a broad look at the site’s history and prospects. The developers declined to comment beyond confirming the recent buyout of Kushner.

Progress for Dumbo, but lingering worries

Despite bringing a flood of residential units to the neighborhood, 85 Jay–which may well get a more uplifting brand name–should have no trouble attracting interest. “The demand to live in Dumbo is still very high,” observes Alexandria Sica, executive director of the Dumbo Business Improvement District. “We think it will be very successful.”

“We are particularly excited for Jay Street continuing to develop as a retail corridor,” Sica adds. “The dead zone that is the 85 Jay block will now feel very alive.” The new residents are likely to help support merchants in the less popular part of Dumbo, on Jay and Front streets, which “definitely struggle from time to time.”

Recently installed protective barriers extend beyond the existing sidewalk and into the surrounding streets (Photo by Arden Phillips)

The site inhabits a significant socio-economic and psychological gap between prosperous Dumbo and the Farragut Houses, a NYC Housing Authority development catercorner to the southeast. Consider: just west of 85 Jay is Dumbo Kitchen, an upscale cafeteria with al fresco seating, while just east is Annie’s First Wok Restaurant, a Chinese joint with a plexiglas-fortified counter, an old-Brooklyn security tactic.

The new development, says Sica, will help connect Dumbo to the Brooklyn Navy Yard and also create an “very active streetscape” for students going to PS 307, situated in Vinegar Hill opposite the Farragut Houses. The school was rezoned in 2015 to accommodate more students. (Some new residents presumably will consider private school, as well.) Coming improvements at Bridge Park 2, a patch of pavement between the York Street F-line subway station and Farragut, she notes, will bring benefit to all.

More wary is Doreen Gallo, a founding member of the Dumbo Neighborhood Alliance. “There’s only one subway entrance, so no matter what they build there, it’s going to be crazy, it’s going to be a very dangerous environment,” says Gallo. City Council Member Stephen Levin of District 33 acknowledges he hears “a lot of anxiety about the overall size and scale of the project,” but expects to meet with the developers to discuss some near-term issues, like scaffolding and parking. “This is going to be such a massive project that it’s in their interest in being a good neighbor.”

If Sica and Gallo see 85 Jay from different angles, they agree on one thing. The plan for the site is more promising than the Watchtower group’s plans more than a decade ago for a manufacturing plant and later an office-residential complex. The current project opens up the site to the neighborhood, with ripple effects, while the Jehovah’s Witnesses handled services in-house, from food supply to repairs, creating a community unto themselves. Nor could they include retail in their projects.

Sizing up the project

Though the developers aren’t ready to discuss plans publicly, we can consult information on file. According to plans filed with the city’s Department of Buildings, there are rental and condo lobbies on both the north and the south. Amenities will include a lounge, game room, grill area, kids area, and screening room. Both the condos and the rentals will have their own rooftop swimming pool.

The project includes 60,000 sq. ft. for commercial space, offering a significant perimeter for retail and other uses. And there would be a huge underground parking lot, enough for 712 cars, with an entrance on York Street. CityRealty commented in March, “Nonsensically, thanks to zoning requirements,” the 712-unit garage will be built on the sublevel “despite there being two subway stations nearby.” (Just up the hill from Dumbo is the High Street-Brooklyn Bridge station on the A and C lines.)

The diagram submitted to the city shows scale, mass, and outlines but scant design details (Diagram via the Department of Buildings)

It’s not the tallest building in Dumbo–the J Condo across Jay Street rises 337 feet and 90 Sands up the heights stands 378 feet–but it will be by far the largest. In fact, if the building brings in 1,400-plus residents, it would significantly swell Dumbo’s population, which was 3,604 as of 2010 and is currently (according to Sica) north of 5,000.

Those looking for duplex penthouses will have options. It’s not clear whether any of the units will be below-market. “It would be great if they were to do some affordable housing,” says Levin, but it’s not required, because of a rezoning for the Watchtower in 2004. (More on that below.) He calls it a development “of its time,” before the de Blasio administration’s mandatory inclusionary housing. “If it happened today, there would be 30% affordable housing, off the top.”

Sizing up the ownership

While 85 Jay has often been described in headlines as a Kushner project, that was never accurate. Bloomberg reported in April that Kushner and LIVWRK owned only about 5% of the project, though they’d get half of the $23 million in development fees, indicating they’d manage the process. Rather, some 95% was owned from the outset by the Los Angeles-based CIM Group, an investment firm that works for institutional investors like major public pension funds.

CIM keeps a very low profile, but as it describes itself in a press release, “CIM Group is a leading real estate and infrastructure investment firm that since 1994 has systematically and successfully invested in dynamic and densely populated communities throughout North America.” In May 2017, WNYC reported that “CIM has done at least seven real estate deals that have benefited Trump and the people around him,” and that various ventures, including a global infrastructure fund, could benefit from the Trump presidency.

It was easy shorthand, but misleading, to describe 85 Jay as a “Kushner project” (Photo-illustration by Heather Jones)

CIM began investing in Brooklyn more than a decade ago, and last October acquired 16 Court Street, a 36-story Downtown Brooklyn office building built in 1928. The Real Deal in March ranked CIM as the borough’s sixth-most-active real-estate developer. Its other big project, with the Brooklyn-focused LIVWRK, is 109 Montgomery St. in Crown Heights.

Dumbo has been home to some other very big deals, notably for office properties. In 2013, a consortium including Kushner, RFR, LIVWRK and Invesco–with the latter owning some 90%, according to The Real Deal–paid $375 million for five former Watchtower buildings that were later renovated and dubbed Dumbo Heights. (Invesco has since been bought out.)

And in 2015, Kushner, LIVWRK, and CIM bought the Watchtower’s longtime headquarters, a former Squibb factory, for $340 million, to be redeveloped for office space. (LIVWRK’s founder and CEO Asher Abehsera was formerly an executive with Two Trees Management, the major redeveloper of Dumbo.) Kushner’s stakes in both the headquarters complex, dubbed Panorama, and 85 Jay have been sold to CIM, the New York Post recently reported, with CIM saying Kushner wants to focus attention on projects in which it holds a larger stake.

Example of a Morris Adjmi building: One Hill South in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Alan Karchmer, courtesy of Morris Adjmi Architects)

What might it look like?

What kind of architectural style will characterize 85 Jay? All we have so far is the massing model filed with the Department of Buildings and posted on the fence at the construction site. Morris Adjmi Architects, however, are no Brooklyn rookies. According to their website, they aim to “create buildings that are contextual but unmistakably contemporary–buildings that may not feel like they’ve always been there, but feel like they should have always been there.” So Adjmi works a lot in older neighborhoods: consider the brick-plus-new-glass Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg, the 11-story Williams tower in Williamsburg, and the new High Line Building on 14th Street that stands on an old industrial base.

For Adjmi’s larger work–which 85 Jay would exceed–examples can be found in Landmark West Loop in Chicago, a 31-story building reflecting industrial history and the city’s Modernist tradition, and One Hill South, a 13-story building near Capitol Hill in Washington DC, a glass-clad concrete structure.

What happened here, back in the day?

The 85 Jay site, which once contained many separate buildings, has a textured history. The cleared parking lot, till recently behind a metal corrugated fence, is just a dozen years old. According to a January 2018 notice from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), the site by 1887 housed industrial and manufacturing uses, with the Bradley White Lead Co. “and/or” Lenox Smelting present between 1887 and 1989. An electrical substation occupied the site’s western part from about 1904 to 1950. Other occupants included a brewery and a paper-goods company.

The block was also home to P.S. 7, which urbanist Thomas Campanella described (with photos) as “a fixture at 141 York Street for well over a century, set in a dense block of industrial buildings.” That’s where the future gangster Al Capone, who grew up nearby on rough Navy Street–since demolished for the BQE–went to school.

The site is three blocks from the East River and one block from the Brooklyn Queens-Expressway (Map from New York State Department of Environmental Conservation)

By 1996, all was demolished. Watchtower, long headquartered in Brooklyn and savvy in its real-estate activities, began assembling the site in late 1980s and early 1990s, aiming to build a manufacturing facility (presumably a printing plant), according to a 2004 City Planning Commission report. Instead, they upgraded existing printing facilities and planned to move that work out of Brooklyn.

In 2004, they won a rezoning from City Council to build residential and religious facilities, planning four towers with 1,000 apartments, a 1,600-seat cafeteria, and a 1,100-car garage to relocate parking previously on Pier 5 of what would become Brooklyn Bridge Park. Neighbors objected, but the deal went through after relatively modest downscaling, as the Brooklyn Paper reported, also publishing an image of the planned complex.

The Witnesses promised, according to former Council Member David Yassky, to make upgrades to the adjacent Bridge Park 2 and the York Street F station. The upgrades to the park are still being designed, but the Watchtower recently contributed $7 million for that work. The subway upgrade wasn’t locked down in writing, apparently.

The Olympic arena that didn’t happen

The site’s size and location intrigued those planning for the 2012 Summer Olympics, so they proposed a new venue there. A September 2000 city press release predicted that “The East River Arena, a 12,500 seat, multi-sport indoor facility, would be constructed on the Brooklyn waterfront, for indoor volleyball.”

Well, not only did New York City not win the Olympics, it didn’t win the site. “We always knew that we needed to build an arena,” recalls Alexander Garvin, the eminent urban planner who led planning for NYC2012, the Olympics effort. “We did a beautiful plan, by Rafael Viñoly. I remember, [NYC2012 founder] Dan Doctoroff and I going to visit the leadership of the Jehovah’s Witnesses: we wanted them to sign a letter saying they would consider selling us the site so we could build an arena. They refused.”

Had New York City won the 2012 Olympics, and the site owner had cooperated, Dumbo might have had an arena (Image courtesy of Rafael Viñoly Architects)

Architect Rafael Viñoly, Uruguayan-born and New York-based, in a 2002 book documenting his work, reflected on designing a “multi-purpose volleyball and handball arena.” Given the “gentle north-south slope,” his firm proposed an elevated plinth with a public plaza, and a “sliding seating system easily configured to suit either volleyball or handball.” A translucent fabric tensile roof would glow at night.

“At the conclusion of the Games, the facility would be turned over to the community,” Viñoly wrote. “The easily reconfigurable seating would allow it to accommodate a wide variety of functions, including concerts and trade shows” as well as sporting events. That would have bequeathed a different Dumbo.

A subway station under stress

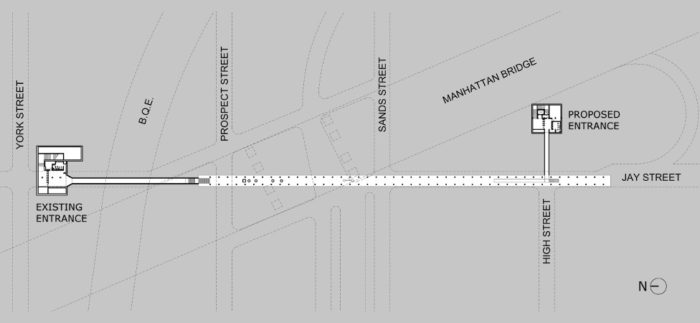

A looming question for Dumbo at large, and 85 Jay in particular, is the capacity of the F train stop at York Street, an awkwardly laid out, stroller- and senior-unfriendly station with a very long, deep ramp, a single platform, and no exit at its southern end.

Average weekday ridership has grown steadily, given the increasing residential and commuter population, plus visitors drawn by Brooklyn Bridge Park, from 5,131 in 2007 to 10,246 in 2016. That resembles the total at two larger stations with twice the number of platforms, tracks, exits, and train lines: the Seventh Avenue F/G stop in Park Slope (11,897) and the Church Avenue F/G stop in Kensington (10,151).

A new entrance at Jay and High streets, as well as a reconfigured current entrance, could vastly improve the York Street F station (Image courtesy of Delson or Sherman Architects)

No wonder Dumbo architect Jeff Sherman in 2016 proposed (see Brooklyn Paper coverage) two fixes to ease congestion and add capacity: a revamped entrance at York Street, with more turnstiles and a relocated staff booth, and new second entrance–with ramps and elevator–near High Street, at the other end of the station, closer to the Dumbo Heights office complex.

“But what feels annoying on an ordinary day becomes life threatening in an emergency. In case of fire or a bomb scare, the station is a corked bottle,” states a petition that drew 493 signatures, some with urgent comments like, “I have been living in Dumbo for 9 years now and cannot believe how overcrowded and dangerous the subway lines have become.”

Sherman says he has drawn informal support from some at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority but the official cold shoulder. Multiple queries by this reporter to the MTA went unanswered. Observes Levin, “This subway station needs a massive amount of work, and it can’t wait forever … it’s in the interest of all of that economic development.”

A project approved in another era

One reason the site cost so much is that it came with few fetters. “This is a rare opportunity to acquire a substantial property that has by-right development potential for a mix of uses,” said Shaul Kuba, co-founder and principal, CIM Group, in the press release announcing the deal. Indeed, no rezoning is required, thanks to a quirk of history and, at least in hindsight, some unwise planning.

As several elected officials and community leaders wrote in a January 2016 letter to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, “[A]s 85 Jay Street was to be used for not-for-profit use only, there were no commitments to provide affordable housing as part of the 2004 rezoning. This means that if 85 Jay Street is conveyed to a residential developer under the current zoning, that developer will be under no obligation to build a single unit of affordable housing. This would be a terrible outcome for the community … If 85 Jay Street were rezoned today, it is very likely that affordable housing would be required in some form.”

The latter observation is indubitable. It’s unclear whether the developer will take advantage of any provisions that offer tax breaks for affordability, but no announcement has been made. (Gallo, a signatory to the letter, charges that city officials misleadingly indicated at the time of the rezoning that any alternative project would have to go through the city’s land-use process.)

A view of 85 Jay looking southeast, with the red-brick Farragut Houses in the distance (Photo by Barbara Eldredge for Brownstoner)

In December 2015, Tucker Reed, then president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, proposed in a Crain’s New York Business op-ed that the group–which, after all, had saved on taxes via its tax-exempt status–donate “5% of their latest real estate proceeds, about $50 million, toward local public amenities” like a new public school, improved subway stations, and the Brooklyn Strand parks initiative.

But the Witnesses pushed back on such entreaties. “When no one was investing in the neighborhood and buildings were becoming decrepit, we were investing heavily in the neighborhood,” a spokesman told the New York Times. Indeed, though the investments by the Walentas family’s Two Trees Management began to bear fruition with the 1998 conversion of the Clocktower Building, Dumbo as of 2004 was not the tourist and residential magnet it is today.

Adding poignance to that missed opportunity is the juxtaposition of 85 Jay with Farragut Houses, the 1952 public housing project, subject of a 2017 short documentary released by Brooklyn Community Services, The Forgotten Farragut. Says Levin: “I think it’s important that, as there’s large economic development happening in Dumbo, that Farragut would be able to participate. It’s hard to do without a rezoning mechanism.”

A toxic legacy, cleaned up

“When I lived in Dumbo I asked people what was up with this lot,” wrote one Brownstoner commenter in December 2015. “Everyone gave the same response[:] ‘the site has contaminated soil.’” Indeed, it does. But the site “does not pose a significant threat,” according to the New York State DEC, in consultation with the state Department of Health.

Current excavations at the site, observed through the construction fence, are part of an environmental cleanup (Photo by Chesher Cat for The Bridge)

The cleanup is being performed and funded by the developer (with state oversight), and the developer may get tax credits to offset those costs. According to a January 2018 notice from DEC, remedial activities were expected to begin that month and continue for one year. Some 72,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil, a legacy of the site’s lead smelter, will be removed.

“Contamination consists of various metals, primarily lead, along with numerous Semi-Volatile Organic Compounds [SVOC]. Some of the soil may be treated to stabilize the lead prior to off-site disposal,” the notice states. “An additional 96,000 cubic-yards will be removed to accommodate the proposed redevelopment project.

A site of inspiration

The 85 Jay site has been a blank canvas for many an architect. New York-based Handel Architects was commissioned by the new site owners to prepare a design proposal. Their concept, which wasn’t chosen, involved four separate buildings around a publicly accessible central courtyard, with sky bridges connecting the buildings that “create dramatic views into the site.”

The architects were inspired by architect Moshe Safdie’s “classic Habitat 67,” a model project built in 1967 in Montreal: “To maximize views and create a distinct profile on the skyline, the residential modules shift in and out along the facade, giving the appearance of stacked boxes.”

The Handel Architects plan for the site involved four separate buildings around a publicly accessible central courtyard (Image courtesy of Handel Architects)

Recently, architecture professor and urban historian Peter Laurence, of Clemson University in South Carolina, had some first-year graduate architecture students address a “tall building” competition, and they chose this site. “The special challenge of the Dumbo site was its sheer size,” Laurence observes. “On one hand it allowed ample public and social space, but on the other this of course requires careful programming and design to prevent it from becoming a tower-in-a-park, and a site that large seemed to realistically require a certain volume of construction.”

One proposal (below) from the group, from student Lillian Jones, was to create a “permeable transition, or flux,” recognizing the socioeconomic gulf between Dumbo and Farragut. A residential block would provide views of Manhattan, while the “office/factory block allows for a collaborative atmosphere,” she writes.

That, theoretically quite interesting, pays homage to Dumbo’s past and future, recognizing the benefit of a mixed-use block. But the residential rezoning train had already left the station, so Dumbo will, by 2021, begin absorbing a new population, and a new kind of flux.

This class project by Clemson University’s Lillian Jones posited not just apartments but also offices and factory space (Photo by Peter Laurence)