Inside the Blight of Empty Brooklyn Storefronts

Greedy landlords? Not so simple. The haunting retail vacancies have many causes–and need a concerted response

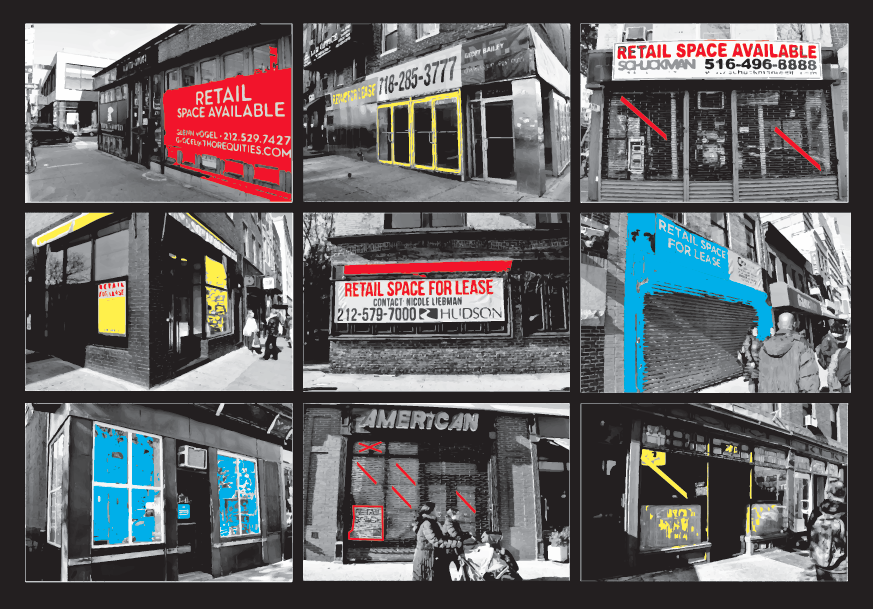

(Illustration by Heather Jones)

After I moved to the Cobble Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn four years ago, I quickly developed favorite local haunts. I bought books at BookCourt and Community Bookstore, beer at American Beer Distributing Co., coffee at Cafe Pedlar, and candy at Sugar Shop, all along Court Street. Some of my favorite restaurants were Brucie and Dassara, and some of my favorite bars were Strong Place, Buschenschank, and Last Exit.

Today, not one of those businesses remains.

Small businesses in New York City are increasingly being forced out of their spaces—frequently from a rent hike, though not always. In their place, outposts of national chains appear, or, in many cases, the space sits empty—for months and months, and sometimes years.

In a city of walkable neighborhoods, the problem is right in your face, and dispiriting. Consumers, politicians and the media have taken notice. This month, the New York Times editorial board asked, “Why is New York full of empty stores?” And Crain’s New York Business examined proposals to address the issue. Even the real-estate industry, which generally benefits from rising prices and rents, is alarmed. “Some areas of the city are retail deserts. It’s really terrible. I think it directly affects the community,” says Louis Puopolo, co-head of operations for Douglas Elliman Commercial.

The former home of American Beer Distributing has been empty for three years (Photos by Steve Koepp)

When seeing another storefront papered over, most Brooklynites cast blame with a handy epithet: Greedy landlords! True enough in many cases, but the causes are more complicated. They include rapidly rising property values, retiring shop owners cashing out of their properties, strict mortgage terms by banks, the arrival of major chains and e-commerce, and the stalling of legislative proposals to help small business survive.

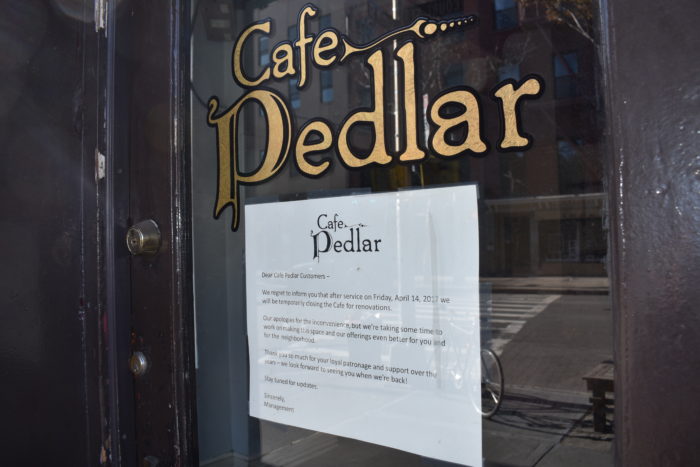

What happened to the businesses I mentioned? BookCourt’s proprietors got $13.6 million for their two-building property, which is being renovated for undoubtedly upscale purposes; Community Bookstore is now a Compass real-estate agency; Pedlar has had a sign up about “renovations” since last April, but no sign of life since then. Strong Place closed last month. Sugar Shop closed in January and still sits empty. Last Exit sat empty for three years until a craft-cocktail bar opened there this summer. Buschenschank, a huge space, has been empty for a year. Dassara sat empty for eight months before a new restaurant opened there in January.

American Beer Distributing is the most stark example of the overall trend. The spacious store, which had been on Court Street just below Kane for almost 70 years, closed up shop three years ago. The space still sits empty, with its original sign still haunting passers-by.

A Bubble That’s Bursting

The cycle of what’s happening in Brooklyn is in its later stages in Manhattan, where retail rents rose 90% between 2010 and 2014, faster than retail spending was rising, according to the real-estate firm CBRE. During that period, a speculative luxury-retail frenzy unfolded, with rents in chic downtown shopping districts rising to astronomical levels.

Rents in Soho, for example, reached $860 per sq. ft., or $4.3 million a year for a 5,000-sq.-ft. storefront, the New York Times reported. A similar fever gripped the West Village’s Bleecker Street, “whose commercial rents and exclusivity rivaled Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Calif.,” the Times noted.

A sign told customers that Cafe Pedlar was closed for renovations, but it has been empty for seven months

Turns out, however, that not even upscale national brands like Marc Jacobs and Ralph Lauren could afford those rents for long, and now parts of Manhattan are pockmarked with empty stores. As a result, retail rents are collapsing (except in super-premium corridors like Fifth Avenue), in what the real-estate industry has started calling “the retail apocalypse,” the worst slump in 17 years.

In June, mayoral candidate Sal Albanese commissioned a survey of the Upper East Side that found 145 vacant shops in a 114-block area. “We have a small-business crisis on our hands,” Albanese declared, pinning it on Mayor de Blasio, which may not be completely fair, though The Times noted in its editorial, “coming to grips with the problem has not been a de Blasio administration priority.”

Now It’s Brooklyn’s Turn

Especially in its affluent brownstone neighborhoods, Brooklyn’s own upscale retail corridors emerged. CPEX Real Estate finds in its 2016 Brooklyn Retail Report that the Brooklyn retail market “has broken into the top 10 nationally in terms of pricing.”

Three of the 10 priciest retail corridors in the entire U.S. are now in Brooklyn: Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg ($350 per sq. ft.); Fulton Mall in Downtown Brooklyn ($250); and Court Street between Montague and Atlantic in Brooklyn Heights ($200). “Brooklyn retail,” CPEX writes, “has reached levels on par with the top retail destinations in Chicago, San Francisco, and Miami.” To Brooklynites who cherish a neighborhood vibe, that’s a scary image.

The increases are fueled in part by the arrival in Brooklyn of deep-pocketed national chains, many of them selling apparel, fast-casual dining and beauty care. The Lululemon athleisure shop opened on Smith Street in 2013. Pricy clothier Rag & Bone debuted on Court Street in 2014, replacing Downtown Bar & Grill. Marine Layer clothes and Benefit cosmetics both opened on Court Street in 2015. Eyewear maker Warby Parker landed on Bergen Street last year. Bonobos, now a subsidiary of Walmart, opened on Court Street this year. And CVS, Duane Reade and Rite Aid are as ubiquitous as Starbucks.

“The chains are coming,” says Danielle Cyr, a legal recruiter involved in Brooklyn community efforts like Save Pier 6 and Save the View Now. “It’s like the chain-ification of the world. If you’re Baskin-Robbins and you want to continue to grow, you have to go into places that don’t want you.”

At Smith and Baltic streets, three of the four corner storefronts remain empty

To some degree, the arrival of national chains have brought benefits to Brooklyn residents, who were long underserved by retail stores, especially when it came to clothing and groceries. In a phenomenon that economists call “retail industry leakage,” where demand for a product exceeds supply in a given area, Brooklyn was losing an estimated $5.8 billion a year as shoppers went elsewhere, according to a report for the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. Those national chains bring more jobs, lower prices and often entertaining shopping experiences. National brands like Nike, Saks Off Fifth, and Century 21 all opened up stores in Brooklyn in the past two years, often in newly constructed buildings.

But if they take over too much of the market, then how is Brooklyn different from the aforementioned Chicago, San Francisco and Miami?

The Phenomenon of ‘High-rent Blight’

When a neighborhood’s property values go through a period of rapid escalation, its retail corridors can go through a cycle of turnover often called “high-rent blight.” Early-pioneer retailers, who benefitted from low rents and enhanced the street life of a neighborhood, become victims of their own success when their rents double or triple. They often try to pay the new rents, but fail under the burden, or they just throw in the towel. Result: vacancy.

Brooklyn’s Smith Street is a classic example. Last year, local news site DNAinfo (may it rest in peace) catalogued more than a dozen closings along the strip. Right now, at the corner of Smith and Baltic streets, three out of the four corner storefronts are deserted, just a block from the Bergen Street subway station. “I walk down Smith Street every day to go to work and I can’t believe what is happening,” says Kathleen Stack, an elementary-school social worker who has lived in Carroll Gardens for 24 years. “Some blocks are so desolate that in winter’s darkness I feel unsafe and have flashbacks to Smith Street before its renaissance.”

Hard to miss the clamorous signage, which is bigger than most existing businesses might have

The storefronts that don’t become the home of a national chain, or the launch pad for a startup that managed to come up with financing, are sitting dormant for as long as three years. If no business can afford the rent being asked, shouldn’t the landlord eventually ask for less?

Not necessarily, says Isaac Erlich, a residential and retail landlord who owns buildings in Cobble Hill, Park Slope and other neighborhoods. “Rents have gone up, but that’s not why the stores are closing,” he says. “Malls are closing. Sears are closing. More and more people are buying on the internet, where they get free shipping, free returns. And then, a lot of these new shops overreach, the market just can’t support them. There was a shop that opened up in Cobble Hill, it had the most expensive bikes I’ve ever seen. It was ridiculous. So it’s not one easy answer here.”

Indeed, the brick-and-mortar retail industry at large is in a death spiral as e-commerce kills foot traffic, particularly in malls. Last year, Sports Authority, Quiksilver and Wet Seal all filed for bankruptcy. This year, RadioShack closed 1,000 stores, Macy’s closed 100, and Sears almost 200. The Atlantic called it “the retail meltdown of 2017.” That’s part of the reason Brooklyn is so attractive right now to chains looking for fresh turf: it has a population of 2.6 million, rising affluence, and a culture of shopping-by-walking-around.

The Landlords: How Much at Fault?

The popular image of Brooklyn landlords is someone who bought the property a long time ago at a low price and may not even have a mortgage anymore. In some cases that’s true, and good tenants can benefit from a landlord who appreciates a long-term relationship rather than big bucks. “A lot of moms and pops own their building and are happy with a tenant paying a little over the going rate. Not all of them are trying to hit it out of the park,” says Douglas Elliman’s Puopolo.

But in other cases, the landlord may have a big mortgage to pay because of buying the property at high current prices, say, or inheriting the property and refinancing it to buy out siblings. “It can depend on how the landlord is financing the property,” says Puopolo. “A landlord may have to satisfy the bank’s requirements for the rent and the credit quality of the tenant.” That’s part of the reason landlords want to rent to big companies rather than risky ventures like restaurant startups. “It’s not just because they can pay 20 grand a month, it’s that they have triple-A credit. Bank of America is not likely to go bankrupt.”

This purpose-built retail venue on Court Street was finished months ago, but no tenant has shown up yet

Puopolo’s colleague Max Dobens, who runs Douglas Elliman’s Brooklyn operations, puts some of the responsibility on brokers to persuade their landlord clients to be realistic about the marketplace, but landlords come in all sizes and business plans. “If they own hundreds of properties, they may want to get what they want to get, and they don’t care [how long it takes]. But if it’s somebody who owns the building and there are residential apartments upstairs, and it’s a smaller commercial space, and that money is important to them, [the broker] has to be like, ‘Look, it’s been on the market for six months and we’re not getting any bites. So if you want to get a lease signed, you need to lower the rent.’ And either they listen or they don’t.”

At some point Brooklyn’s fast-rising rents will follow the example of Manhattan’s, to some degree. Many prospective tenants are betting on it. “I really see this as a sort of normal cycle,” says Puopolo. “It will get to a point where, ‘Hey, that’s a good deal,’ and the tenant will start coming back. A lot of tenants are on the sidelines, looking at the bloodbath and waiting it out, staying with their online or other business for now.”

What can be done to reverse the trend?

From a business perspective, the disruption is inspiring new entrepreneurs to try new things in retail. At a Brooklyn real-estate conference in October, Paul Travis, managing partner of Washington Square Partners, the group that developed City Point, cited the phrase “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste,” and added: “It’s allowing a lot of innovation in retail and in Brooklyn.”

After the beloved BookCourt closed, Brooklyn-dwelling bestselling novelist Emma Straub and her husband opened up a new-generation indie bookstore, Books Are Magic, putting a heavy focus on events, social-media and children’s books. (The store has 18,600 followers on Instagram.) Ample Hills Creamery pioneered the idea of ice-cream parlors as entertainment venues, tying their flavors to pop-culture themes. Two young entrepreneurs opened a store in Williamsburg that became the launchpad for their startup, Bulletin, which provies a kind of “WeWork for retail,” serving multiple merchandisers.

The countertrend: New bookstore Books Are Magic has won fans with engaging events, social media and this interactive street mural (Photo from Books Are Magic via Instagram)

The market seems to be responding to that kind of “experiential” retail, in which customers have a deeper engagement with a store and its proprietors. Bloomberg reported this week that spending growth at mom-and-pop shops has outpaced the big chains for the past two years. “Many of the most affluent consumers are now clustered in walkable neighborhoods, letting them skip the mall in favor of neighborhood hardware stores, bookshops and grocers. And they’re willing to pay the higher prices,” the news service reported.

From a lawmaking perspective, much has been proposed but not much done. The Small Business Jobs Survival Act, which would offer protections for retail tenants, has been stalled in the City Council for three decades, dogged by questions about whether local government has the authority to regulate business contracts.

In a Facebook post that was eventually submitted as testimony last year at a City Council hearing on small businesses, Jennifer DeLuca, owner of the Body Tonic pilates gym in Park Slope, suggested “creating an area of Brooklyn set aside for businesses with fewer than three locations,” among other ideas. “Rents could be capped at certain amount based as a percentage of current market or subsidized… This unique area would likely become an ideal shopping and tourist location.” The Bridging Gowanus project includes something close to this.

Among other ideas raised at the same council hearing last year: restrictions on chains like Starbucks and Walmart; regulations on storefront sizes and use, and “no vacancy” incentives that would ideally dissuade landlords from keeping spaces empty for years.

But how many of those ideas are realistic? That was one year ago. Councilmember Brad Lander, in a post after that hearing, acknowledged, “We don’t currently have good policies in place (or even good data about the problem) to help preserve the small businesses and neighborhood retail diversity that we treasure.”

If you are a dismayed local, there are community groups worth monitoring or joining, like TakeBackNYC, Alliance for a Human-Scale City, Carroll Gardens Association and FROGG: Friends and Residents of Greater Gowanus, among others.

Even so, many feel frustrated about forces at work beyond their control. “I’m not an activist, but I’ve been fantasizing about what power we community members might have in this situation,” says Stack, the social-worker. “If we in the community are the potential customers of the businesses that landlords are trying to attract to the neighborhood, then we have power, we just have to figure out how to wield that power. I’ve thought of going down Smith and collecting addresses of storefronts that have been vacant for years, then looking in public records to see who owns the buildings as a first step. But frankly, like most people here, I’m pretty busy working, taking care of my kids.”

For now, at the very least, there’s the old saw: vote with your wallet. When you can, shop local.

An earlier version of this story said the space vacated by the closed restaurant Dassara had been empty for 18 months. In fact, it was vacant for eight months before a new restaurant opened in its place.