BBQ in BK: Hill Country Cooks Up a Diverse Taste of Texas

For years, Hill Country has been best known for serving up high-quality Texas-style barbecue and tasty fried chicken in New York City and Washington D.C. But now the regional chain is taking a bold new step with the recently opened Hill Country Food Park, a “micro food hall” that serves a multitude of culinary styles under one roof including barbecue, tacos, pizza, burgers, and fried chicken.

It’s a significant addition, with a new twist, to Brooklyn’s barbecue scene. Housed in a building that was once home to an earlier iteration of the brand—Hill Country Barbecue Market and Hill Country Chicken, which was closed due to underwhelming performance—the food park is a new chapter in the company story that started in 2007 when Marc Glosserman opened the first Hill Country Barbecue Market in Manhattan.

For this version, Glosserman said he and his team were inspired by Austin’s immense food-truck scene. “I visit Austin about three times a year, and I love it,” Glosserman said. “The first time I ever ate at a food truck was in Austin. There has been a lot of innovative food out of food trucks there and around the U.S.”

The delicious baby back ribs are an item you can’t get at any other Hill Country location

Austin’s food-truck scene has nearly anything you can think of, including barbecue, pizza, tacos, Mediterranean, and lobster rolls. That level of diversity is present inside Hill Country’s food park, which has six “stalls” where you can go up to any counter and order a little bit of this and that to make a customized meal.

“We’ve been serving up a pure, unadulterated version of Texas barbecue since 2007,” Glosserman said. “We used the opening of Food Park as a license to be more creative.”

Branching Out From Texas Barbecue

When you first walk into the food park, the array of options makes it easy to be indecisive. Your mood (or your stomach) will help guide you to the right stall. Let’s go over them quickly:

- Austino’s serves “Austin-style” pizza and features freshly smoked meats from Hill Country Barbecue as toppings.

- Bluebonnets serves fresh salads and healthy sandwiches.

- Hill Country Barbecue offers barbecue, sandwiches, and sides, with a slightly smaller menu than other HC locations, plus one exclusive item—baby back ribs.

- Hill Country Chicken offers a pared down menu from the other HC Chicken location with fried chicken, sandwiches, and sides.

- Nickie’s serves Tex-Mex staples including tacos, nachos, burgers, and hot dogs.

- South Congress is focused on breakfast and sweets, serving coffee, breakfast tacos from King David Tacos, doughnuts from Du’s Donuts, and ice cream from Brooklyn’s Van Leeuwen.

Offering this many choices is risky because it’s hard enough to control quality at one type of restaurant, let alone six different ones. But one benefit of these six being housed under one roof is the possibility of combining offerings together. Freshly smoked brisket and pork from the smokers at Hill Country Barbecue are used in the tacos as Nickie’s and on top of pizza at Austino’s. Glosserman said this cross-pollination may happen even more as time passes.

Tapping into the Food-hall Craze

While it might be easy to call Hill Country Food Park a “food hall,” it’s ultimately a bit different than places like DeKalb Market Hall at City Point or the new Japan Village in Sunset Park. Glosserman calls it a “micro food hall” because there are just six vendors and all of them are operated by Hill Country.

Big windows and a spacious interior give the place an open, almost outdoorsy vibe

But the American food-hall craze that has taken hold New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and other cities certainly did inspire the design and feel of Hill Country’s version. Large windows make the space feel larger than it is. Downstairs has lots of open seating while upstairs features a small area with a few tables and Skee-Ball.

“Food halls are great, and they are not just a New York thing,” Glosserman said. “New York is a precursor of trends and that’s why we’ve seen so many here and many open in other cities after.”

In its current form, Hill Country’s focus is on lunch and early dinner. The space is open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m., but until 11 a.m. only the South Congress stall is open for business. This makes sense, as lunch is prime time, with majority of business is coming in between 12:30 to 2 p.m. With Downtown Brooklyn becoming increasingly dense with office buildings, the food park has a prospective clientele of hungry office workers looking for good, quick bites.

How’s the Food?

I’m happy to report that Hill Country’s food quality is good, given that the place has been open for only about two weeks. Almost everything I tried was pleasing, if not out-of-this-world, whether it was tacos, sandwiches, or salads.

The park’s managers provided some food for sampling on one visit, but I also stopped by few times unannounced to get a better sense of the real experience. The samples served by Hill Country were a little better than what I tried when they weren’t looking, but thankfully not by much.

One of the most exciting items is the El Original pizza, topped with Hill Country smoked brisket

My personal three favorites were the El Original pizza from Austino’s, which is topped with brisket, mozzarella cheese, green onion, and pickled jalapeno; the baby back ribs from Hill Country Barbecue; and the Lone Star Burger from Nickie’s, which is a blend of brisket and short ribs that’s topped with a fried egg, salsa verde, and American cheese. As a barbecue aficionado, I appreciated the baby back ribs because they often are served overcooked and tasteless, while these were rich in flavor and had a little kick.

By contrast, Glosserman told me his favorite three items so far are the Skye Pie at Austino’s (named for his daughter Skye), the El Guapo burger at Nickie’s, and the al pastor taco at Nickie’s.

Glosserman said food quality overall is quickly improving and that the first week was “rough.” He said that some of the first negative Yelp reviews he saw were fair to ding them, but that the second week has produced better results because his team is making little improvements every day.

Cutting up behind the scenes, where the chefs mix-and-match ingredients to create new items

Amongst the six stalls, two really stood out. The most intriguing stand is Nickie’s, which is inspired in part by Texas joints like Valentina’s Tex Mex BBQ, which elevates Tex-Mex to a new level and serves the best BBQ tacos I’ve ever eaten. If the tacos at Nickie’s get anywhere close to Valentina’s, I will stop by often.

The other stall showing serious promise is Austino’s, because the pizza is far better than one might expect for being “Austin-inspired.” This is really a great blend of New York and Austin pizza, with delicious crust and well-chosen toppings. Expertly smoked brisket, pulled pork, and Kreuz sausage are not often served on pizza, but it really makes these slices stand out from other Brooklyn vendors. Now I just wish there was more meat on the slices.

The Austin-inspired barbecue tacos from Nickie’s are among the most notable standouts in the food park

How the Park Will Evolve

The overall flavor of Hill Country Food Park is likely to change in January when Hank’s Saloon opens on the second level of the Food Park. Hank’s Saloon is a beloved Boerum Hill dive bar and music venue that is closing this month, but it will live on in a new form at Hill Country.

When Hank’s opens, the park’s hours will run much later and liquor will be served on the premises. Glosserman isn’t certain what the menu will look like at Hank’s just yet, but said some items from the food park will be available. Like the old Hank’s, the new venue will offer live music.

“We’ve always had a passion for music,” Glosserman said. “It would be impossible to replicate Hank’s, but we are hoping to bring the spirit of Hank’s here.”

Not stingy with the pickle slices on this fried-chicken sandwich

I think Hill Country Food Park will ultimately be successful, especially as a lunch and happy-hour destination. Hank’s will bring in more customers in the late afternoon and evening. Being smack dab in the middle of Downtown Brooklyn has got to help, with its population growing considerably.

As an entrepreneur, Glosserman says he plans on being completely focused on perfecting the food park in 2019, with no new restaurants planned for next year. “Opening a new restaurant is like having a new baby,” he said. “It’s a lot of work, and we have a lot to learn. It’s almost impossible thinking about anything else right now.”

The new version of the beloved Hank’s Saloon is scheduled to open in January on the second floor

Malls vs. Bodegas: Can the City Resist Becoming Suburban?

From the days of street gangs ruling the Five Points to the nights of Guardian Angels patrolling subway cars swallowed whole by graffiti, New York City has a long history of substantive grit. Yet even in the darkest times, the city’s street life has been brightened by its distinctive storefronts and mom-and-pop shops.

Now the city’s edge has been rounded off, with safety and prosperity ascendant. But does that inevitably mean the rise of commercial conformity, with the mom-and-pops substantially replaced by national chain stores? The trend has been particularly notable in Brooklyn, which in 2017 saw the biggest percentage increase in the number of chain stores among the five boroughs, with 1,587 locations, a 3.1% increase from 2016, according to a report last year.

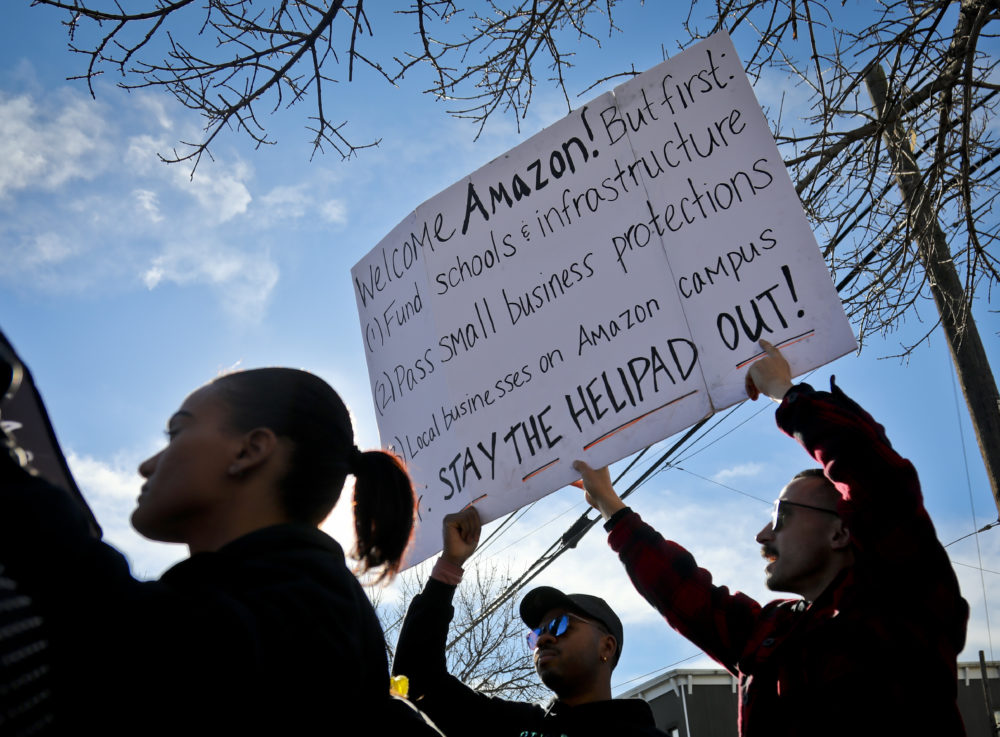

The recent announcement that Amazon, which has contributed to the decline of brick-and-mortar stores, is set to build a triumphant headquarters in Long Island City has been seen as another benchmark in New York’s transition from grime to gloss.

With all that in mind, last week the Brooklyn Historical Society hosted a panel discussion called “Malls vs. Bodegas: Resisting the Suburbanization of the City.” About 120 people poured into the society’s auditorium, situated in Brooklyn Heights, to hear a variety of takes on the city’s cultural shift from local-economy activists, researchers, and thought leaders. Paul Goldberger, the architecture critic and contributing editor to Vanity Fair, served as moderator. Among the highlights:

Fewer Customers, Rising Rents

Early on, the panel focused on potential causes for the disappearance of small businesses in the city, and landed on chain stores right off the bat.

“Twenty years ago there wasn’t a whole lot of big box, national retail in New York,” said Jonathan Bowles, executive director of the Center for an Urban Future, a think tank focused on New York City. “A few early [chain] retailers showed, boy, they can have a lot of success, ring up huge sales in New York. A lot of people didn’t think they could do that.”

New York has since experienced an invasion of national retailers, Bowles said, which landlords love for at least two reasons: the companies have the deep pockets to pay hight rents, and they’re generally reliable, having been vetted by years of success and expansion.

A mainstay: Staubitz Market in Cobble Hill, a butcher shop that has been in business for 101 years (Photo by Crary Pullen)

“And then, three or four years ago, on top of that trend, happened the Amazons, the Zappos, all the online shopping,” Bowles continued. “So we’re seeing all sorts of retail, small and large, that are really struggling to compete, particularly the merchandise retailers … but then it’s happening at the same time as landlords have gotten so used to these kinds of year-over-year, double-digit [rent] increases.”

Bowles said these conflicting cultural developments have helped to generate the glut of vacant storefronts, especially in Manhattan, where a recent study showed 20% of the borough’s retail spaces are unoccupied, up 13% from two years ago.

“People just aren’t shopping right now, there’s not enough customers, but a lot of the landlords haven’t recalibrated their expectations,” Bowles said. “They’re still thinking [like it’s] three years ago where a wave of national retailers are going to come in, and I think it’s changed a little bit.”

A New Opportunity?

Bowles thinks the tide may be turning. While his group’s data shows the number of chain stores ballooning even during the Great Recession, last year the city overall showed just a 1.8% expansion, despite the higher rate in Brooklyn. “Although food establishments continue to show strong growth, retailers that compete most directly with online outlets—such as shoe and electronics stores—have experienced significant contractions,” a summary of the center’s 2017 report said.

Though Bowles’s organization hasn’t released data for 2018 yet, he expects any additional uptick in the presence of chain retail in New York the past 12 months to be minimal, with traditional retailers continuing to be outpaced by food-focused businesses.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” Bowles said. “I’ll just cite a few of the stores that I’ve seen with significant losses this past year: Aerosoles, Club Monaco, Nine West, Ralph Lauren, Claire’s, Best Buy, Radio Shack, Aeropostale, True Religion, Payless, Bolton’s, Strawberry, Sunglass Hut, Lens Crafters.”

Bowles also observed, “Even drugstores like Duane Reade and Rite Aid are down,” which compelled moderator Goldberger to quip: “Duane Reade has actually closed a store?”

Shortly after the audience’s laughter died down, Lena Afridi, director of economic policy at the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development, an advocacy group focused on affordable housing and the building of neighborhood equity, pointed out a different side of the situation. Many of the retailers on Bowles’s list, like Strawberry and Payless, are relied on by low- and middle-income residents for affordable choices, she notes.

The panel discussion played to a full house last week at the Brooklyn Historical Society (Photo by Michael Stahl)

“When those options start to disappear, what does it mean [for those neighborhoods]?,” Afridi posed. Later, she said that her organization is looking to start a fund that will assist people in economically challenged areas to “build out commercial spaces at the bottom of affordable-housing buildings, to, instead of bringing Applebee’s to be an anchor tenant, bring, like, four small businesses from the area in.”

“That would make a huge difference,” Goldberger said.

But with even many national retail stores struggling in the five boroughs, and with all those vacant storefronts, panel members observed that some small businesses might be able to take advantage of a long-awaited softening of commercial rents, which have started to decline along some Brooklyn retail corridors.

“I just don’t think all those empty spaces are going to stay there,” Bowles said. “I think very soon we’re going to see more landlords understand that this is not what it was four years ago, in light of a lot of these online disruptions that we’re seeing. I think there could be some opportunities for independent businesses.”

Bowles then threw out the statistic that independent bookstores in Brooklyn are up 33% the past decade, which sparked some audience applause.

“I’m not saying it’s all of a sudden going to turn 180 degrees,” Bowles went on, “[but] I think there’s some opportunities in the vacancy crisis that we’re seeing.”

Still, as both Goldberger and Afridi pointed out, the rise in the number of independent bookstores—though encouraging and widely embraced—has been concentrated in just a few areas of the city. Afridi, a Queens native, said, “We have two in Queens that are independent; there are zero in the Bronx. So this conversation, when we talk about where are these things happening, we need to push [our] thinking out a little bit.”

A Psychological Shift?

Citing the packed house at the Brooklyn Historical Society and other evidence, Afridi observed that, on some level, there’s “a deep desire” for New Yorkers to revisit the city’s historic culture of personal, public connections. (Of course, commercial spaces help facilitate such encounters.)

Jeremiah Moss, author of both the book and popular blog called Vanishing New York, about hyper-gentrification and the loss of the city’s cherished, mom-and-pop commercial culture, emerged less hopeful for the future of the city’s storefronts—and its soul.

“I see this new psyche has come into New York City that didn’t used to be here, and it’s not just young people, it’s newcomers,” Moss, a practicing psychoanalyst whose legal name is Griffin Hansbury, said. “A lot of it has to do with New York being safer … If you came here, like I did, you accepted a certain level of risk because you had to be here for whatever reason, you had to leave the place you’d come from, and there was a desperation in that. But now you can be risk averse and come to New York.”

He believes that, thanks in part to the advent of smartphones, people who walk the streets of the city can now find themselves cocooned in their own “private bubble,” regardless of the foot traffic in front of them.

“If you interfere with that bubble,” Moss continued, “either they don’t see you—they bounce off you like a wind up toy—or they get irate, enraged [because] they want to have a frictionless experience.”

Online shopping is an extension of this frictionless experience, and both Moss and Goldberger bemoaned the stacks of delivered boxes lining their buildings’ hallways, forming obstacle courses they each have to navigate in order to arrive safely at their apartment doors.

Moss then quoted E.B. White, who said, “New Yorkers temperamentally don’t crave comfort and convenience—if they did they would live somewhere else.” Moss said sharply that New York’s transplants, who are retreating into their bubble of comfort and convenience, “should go live somewhere else.”

“If that’s what you want, above all, then New York’s not the place for you,” he continued. “Cities are not about ‘the easiest way,’ they’re about friction, and they’re about difference, and they’re about creation, and they’re about descent against the mainstream. They’re about a lot of things that are not about comfort and convenience.”

How do we solve this psychological shift?

“We need to shame our friends,” Moss said: Shame them into looking up on the sidewalk, where they should also walk on the right-hand side; into shopping at local, independent businesses; and into engaging with the 8-million-strong community around them.

“There are a lot of new people coming into New York, who don’t know how to do New York, and they need to be told how to do New York,” Moss said as the discussion neared a close. At that the audience applauded, and soon thereafter emptied into the streets and subways, with many of them passing rows of Christmas trees watched over by a young, bundled-up salesman, standing in the glow of a CVS store across the street.

Brooklyn Startup Kitchen Gets a Pre-Holiday Rescue

On Oct. 13, when the abrupt shutdown of the Brooklyn community kitchen on Flushing Avenue called Pilotworks occurred, the survival of nearly 200 small businesses was suddenly put in peril. Without warning, the Pilotworks management sent a mass email to its members about the closure, and ordered anyone on the premises to cease cooking and leave the building. The announcement came just as the all-important fourth quarter, which includes the holiday season, had begun.

In the aftermath, the Pilotworks castoffs banded together, assisting each other in finding any cooking space they could to keep their businesses afloat. Other community kitchens throughout the area offered help as well.

But this past weekend, just as out-of-the-blue as the shutdown itself, former members began receiving emails welcoming them back to the Pilotworks space in an old Pfizer pharmaceutical factory. The messages were from Nursery, a food-and-beverage incubator founded by Adam Melonas and his team at Chew, a food innovation lab in Cambridge, Mass.

“Ahead of the busy holiday season, Nursery has prioritized the immediate restoration of kitchen operations as quickly as possible,” said a statement from the company, released yesterday. Though details about the community kitchen’s rates were not disclosed, “Nursery plans to reopen kitchens later this week, pending final permit approval,” according to the statement.

Former Pilotworks member Anjali Bhargava, the founder of Bija Bhar, which produces a turmeric-based elixr, told The Bridge in an email that she is meeting with Nursery on Thursday to enroll. “I look forward to seeing folks back in the kitchen and hope this will help many businesses recover and get things going while we’re still in the 4th quarter,” she wrote. She also said the news came as “a huge relief” to her because the space housed “an essential piece of equipment” she’d grown reliant upon.

Back in October, the startup kitchen was abruptly closed, with resident companies getting only a few days to clear out (Photo by Michael Stahl)

Chef Rootsie, another displaced Pilotworks member who runs Veggie Grub, a vegan catering service, said in a text message to The Bridge last night: “Yes I’m going back, and extremely excited!”

“We feel so honored to open our doors to this wonderful and inspiring community of makers who are not only disrupting the food and beverage industry, but also helping to create the future of how and what we consume,” Melonas said in the statement. “We understand the abrupt closing of the facility by the previous owners has caused real hardship and pain for many, and we have been inspired by the community’s support of those impacted, as well as the resilience of everyone affected.”

While no one from Nursery was available for comment yesterday, a lengthy Boston Globe Magazine profile of Melonas in June described him as operating out of a “secretive Fenway lab,” adding, “the man who views himself as a modern-day Willy Wonka is reimagining food for the future.” The profile describes how the Australian native criss-crossed the globe from London to Beijing learning from master chefs, including a stint in the kitchen of El Bulli, the now-closed Catalonian restaurant of the legendary Ferran Adria, before launching into the creation of innovative foods for major corporations.

Melonas’s LinkedIn profile says he founded Nursery over a year ago, with a business address listed in Cambridge. Nursery’s terse website simply describes the company as “A CPG (consumer packaged goods) playground where we turn crazy ideas into companies.” The former Pilotworks kitchen appears to be the company’s first brick-and-mortar startup incubator.

The statement announcing the occupation of the Pilotworks space concluded with an outline of Chew’s credentials, saying it boasts “an innovation team of world-class chefs and scientists on a mission to democratize good food & beverage,” and that the company’s “client list is made up of the world’s largest and most influential food and beverage companies and progressive startups.”

A member of the facility at one of its 16 workstations, back when it was still called Foodworks

“Through these partnerships, Chew has created more than 1,400 products,” the statement also said.

While former Pilotworks members expressed enthusiasm about the facility’s reopening, they have reason to be wary as well. In the months leading up to the facility’s sudden closure, there were signs of poor management, including potential unwise use of funds and other indiscretions, as The Bridge reported in October.

Melonas said in the Nursery statement that his company wishes to build trust with its tenants, especially the Pilotworks members, and be more than a “de-facto landlord.”

“We are here to add exponential value to this community and ensure we are working with wildly passionate entrepreneurs, and turning them into viable and impactful companies,” Melonas said.

Some former Pilotworks members have already moved operations elsewhere, however. April Wacthel, founder of Swig + Swallow, which produces bottled cocktail mixers, said in a Facebook message that she has been working out of “her own space, but I wish them the very best.” Andy Barbera, founder of Keto-Snaps, a low-sugar cookie, told The Bridge last night that he’s been working out of the Hana Kitchens location in Sunset Park’s Industry City, which had reached out to Pilotworks members after the shutdown.

Though Barbera said he received no invitation from Nursery to return to the Pfizer building, he called the new incubator’s opening “great news.”

“I’ll bet there are a lot of people that will jump on that” opportunity, he added.

Anke Albert, who owns Anke’s Fit Bakery, told The Bridge this morning that she, for one, will return to the Pilotworks space, though perhaps with a tinge of reservation. In October she told The Bridge, “People had a feeling something was off with Pilotworks,” but in a text this morning wrote of Nursery: “They seem to be a very organized group of professionals. The whole catastrophe might have been for the better. We’ll see.”

In a Buyer’s Market for Condos, a Brooklyn ‘Flash Sale’ Is Telling

Dramatic, desperate, or maybe both? To get the final 32 units sold at the 550 Vanderbilt condominium in Brooklyn, developed by Greenland Forest City Partners, uber-broker Ryan Serhant, of Million Dollar Listing fame, has alerted real estate brokers to a flash sale.

“On this Sunday (December 2nd) we will have a 1-day, 20% OFF SALE from 11am – 4pm,” Serhant wrote in a message to brokers this week, inviting potential buyers in for previews. “Happy Bidding :)” The building, which has 278 units, has faced a roller-coaster ride of sales, strategies, and even a Million Dollar Listing episode in the last three years.

If the flash sale might seem a stunt—would they really decline to offer discounts later?—a citywide slowdown in condo sales reflects a clear buyer’s market. Recent quarterly reports by the real estate brokerages Corcoran and Stribling indicated sales slowing in pricier parts of Brooklyn. Warburg Realty cited “[o]ffers 20% and 25% below asking prices … a phenomenon last seen in 2009,” though it suggested Brooklyn sales at prices below $2 million were reasonably healthy.

The competition among discounted condos in the city is mounting. The Real Deal just reported that Extell Development will pay three years’ of common charges for one- and two-bedroom condos that go into contract by year’s end, and five years of common charges for larger units. That includes buildings like One Manhattan Square, which looms to Brooklyn viewers over the Manhattan Bridge, and Brooklyn Point, part of the City Point development in Downtown Brooklyn.

Broker Serhant meets Hu Gang, president of 550 Vanderbilt’s developer Greenland USA, at an event at the condo building filmed for Million Dollar Listing (Image courtesy of Bravo)

Other developers, according to the Real Deal, will pay closing costs or offer rebates on commissions. Especially choice units can be a tough sell. For example, the penthouse at 1 Main Street in Dumbo went to market in 2011 at an astonishing $23.5 million, then saw its price dropped to $19 million after 18 months, according to StreetEasy. The unit resurfaced at $10.1 million in September, but five weeks later the price dipped to $9.75 million.

Buyers have become skittish, according to Bisnow and the Wall Street Journal, because of rising interest rates, the loss of tax deductibility, and a volatile stock market. Some sellers, Bisnow reported in August, are under pressure from investment partners to move product.

At 550, Millions More to Sell

In certain cases, at least when there’s significant inventory, the developer aims to maintain the unit’s sticker price, so as not to hamper future sales, or antagonize previous buyers concerned about resale value. At 550 Vanderbilt, the only condo building in the Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards) development, that doesn’t seem an issue.

While developer Greenland Forest City Partners declined to elaborate on the rationale for the 550 Vanderbilt sale, some significant savings might be had this Sunday, given that several larger units remain, notably two penthouses, listed for $6.86 million and $7.715 million.

Most units listed on 550 Vanderbilt’s StreetEasy page are two bedrooms or bigger, reflecting that it has been easier to sell smaller, less expensive units. Though StreetEasy doesn’t list all 32 condos, the 13 units listed for sale two days ago had a cumulative price tag of $41.3 million, while seven others said to be in contract had cumulative list prices of $11.5 million.

A panoramic view of the condo, which was designed by the COOKFOX architecture firm, from the rear (Photo for The Bridge)

Add 12 more units to reach the total of 32 said to be on sale, and it’s possible the potential sell-through exceeds $70 million, at least if list prices are met, or $56 million at a 20% discount. The building’s cumulative offering price is $391.2 million, according to the most recent amendment to the offering plan.

The developer, which quickly sold a first tranche of units in China—lead partner Greenland USA’s parent company is in Shanghai—ultimately nudged up prices from a cumulative $388.57 million at the start.

It’s possible 550 Vanderbilt was priced aggressively high, given its current setting. Though Serhant’s website page for the tower touts it as offering “the inaugural opportunity to live and own in New York’s newest park,” 550 Vanderbilt will be bordered by construction sites for years, and Pacific Park’s eight acres of open space, along with the full complement of towers, isn’t projected for completion until 2035.

While previous sales averaged $1,460 per sq. ft., according to StreetEasy, active sales—which include rare penthouses and maisonettes—are priced at $1,658 per sq. ft., at least before the discount. Brooklyn Point also has high prices for the borough; sales average $1,797 per sq. ft., according to StreetEasy, while other Downtown Brooklyn condos cost less, with 11 Hoyt listed as asking $1,575 per sq. ft., The Brooklyn Grove at $1,373 per sq. ft., and 211 Schermerhorn at $1,380 per sq. ft.

Ups and Downs

Along the way, sales at 550 Vanderbilt have failed to match the fanfare. In a July 2015 Real Deal article about the seeming lack of condo inventory in Brooklyn, an executive for brokerage firm Citi Habitats predicted that the building would be sold out by the end of 2016, in time for move-ins.

In September 2015, when the developers opened a sales gallery in Brooklyn, they declared that 80 units had gone into contract thanks to pre-sales, which turned out to rely significantly on marketing in China.

In July 2016, the Real Deal reported that the Greenland Forest City claimed the building was 50% sold, with more than 140 units in contract. But that masked relatively slow progress in closing deals since the September 2015 sales gallery. By mid 2016, based on that pace, it looked like the sell-through could last 20 months, through early 2018.

It wound up taking longer. Indeed, in November 2016, Forest City Realty Trust, the junior partner in the joint venture, announced a unilateral pause in the overall Pacific Park project, noting that, in the third quarter of the year, “the condominium market in New York has also softened, causing the projected sale schedule for 550 Vanderbilt to be adjusted accordingly.”

Marketing for the building has featured its amenities, but price now seems the key (Image courtesy of Greenland Forest City Partners)

Forest City, which had launched Atlantic Yards in 2003 and partnered with Greenland in 2014 at a 30% share to build three towers, began winding down its role. It sold the only tower it built solo, and then this year sold all but 5% of the project going forward to Greenland.

Meanwhile, the joint venture made changes in the sales effort at 550 Vanderbilt. In July 2017, it swapped broker Corcoran Sunshine for Serhant’s Nest Seekers International, claiming to the Real Deal that they wouldn’t cut prices.

However, as reported later, that swap was coupled with an undisclosed maneuver that lowered taxes significantly on higher-end units, effectively reducing the cost of ownership. (Both NestSeekers and developer misleadingly advertised taxes for some units at a bizarre $1.) By December 2017, the developer also began lowering prices on select units.

Riding the Publicity

By some measures, the building’s sales performance looked good. For 2017, 550 Vanderbilt was the second-best selling building in the city, according to Property Shark, with 173 units sold.

Then again, that encompassed numerous units that had gone to contract earlier, including with those 2015 Chinese buyers, many of whom sought investor units. Indeed, Bloomberg last June reported that 550 Vanderbilt, with 41% of its units sold in 2017 up for rent, was the the city’s most popular building for investor condos.

And sales apparently slowed. In October, the Wall Street Journal reported, citing “people familiar with the matter,” that Greenland had underestimated the time it would take to sell condos in New York and in its Los Angeles developments.

Also, as reported for The Bridge in October, a Million Dollar Listing episode portrayed Serhant as having made a Hail Mary pitch—a community smorgasbord—to win the job in 2017 as exclusive broker for 550 Vanderbilt, though the record showed he had already won the job.

Nor did the sticker prices shown during that episode screen reflect what buyers at the event would have been told. Three of the five “list prices” reflected price cuts announced long after Serhant’s big event. As noted, that allowed Million Dollar Listing to portray Serhant as closing deals not far off list price. That strategy, apparently, has been abandoned.

How a Plan to Save Journalism Stumbled Out of the Gate

Combining blockchain technology with a journalism platform, Brooklyn-based Civil has been one of the most talked-about startups in both worlds. Of all the schemes being hatched to shore up journalism with new business models, Civil’s idea was one of the most creative—perhaps inordinately so.

Last month was to be its launch, with a multimillion-dollar sale of the Bitcoin-like token, called CVL, that was predicted to serve manifold purposes including raising money, paying employees, and engaging readers. As it turned out, Civil’s cryptocurrency token sale ended on Oct. 10 with head-scratching failure. In the final days of the token sale, as money barely trickled in, the plan started to evaporate.

The company had set a minimum goal of $8 million for the sale to be a success. If the total were to fall below that level, all the money would be returned. Onlookers waited with interest to see if large donors would come in at the end and lift the company over the threshold. When the end of the day came, Civil had sold only about $1.4 million worth of CVL tokens. In the days that followed, it emerged that $1.1 million of that had come from the founder of its parent company, ConsenSys, meaning that after months of hype, planning, hiring, and hope, the CVL token was stillborn. But can Civil find another way to survive?

The Promise of a New Idea

Since its conception in August 2017, Civil caught the eye of those in journalism as a potentially useful new way to solve the intractable problem of the industry: how to get news readers to pay for what they read.

“The advertising market has just shrunk radically,” explained Sarah Bartlett, the dean of CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. She said she has been following Civil and is intrigued by the project. “The print world has just collapsed and the revenue stream for digital news is still very limited. That’s the internet transformation we’ve seen over the last 20 years or so. Everyone can be a publisher on the internet and there’s a lot of free content out there. I think you’re seeing a move to people expecting to pay for quality news. You’re seeing that in publications that have strong brands, but you’re not seeing it at smaller places.”

The banner of the website Popula, one of Civil’s newsrooms

Civil has seemed to be offering some new thinking on that front, with its seed funding for small publications, plans for a platform of micro-payments, and reader direction in newsroom governance.

Founded by Matthew Iles, whose career had previously been in marketing, Civil aimed to create a payment platform on which readers could donate to their favorite publications with the CVL token. Readers could also use their tokens to have a voice in the governance and management of that publication, if the readers held a sufficient amount of CVL tokens.

“This was one of the most ambitious experiments aimed at creating a brand new model in journalism,” said Mathew Ingram, a writer on the topic of digital media for the Columbia Journalism Review. “Not just to charge readers, but to create a brand-new economic and journalistic platform,” he said. “They came up with a Civil constitution and an advisory council…and it wouldn’t be controlled by a company or a billionaire, it would be owned and controlled by token holders. That was a pretty radical way of looking at how to build a journalistic entity.”

Civil came about at a propitious moment in the life cycle of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology. It was founded just as cryptocurrency values were headed for the stratosphere, when money and enthusiasm were abundant. Civil’s seed money of $2.5 million was invested by ConsenSys, the hyper-fast-growing developer of applications for the Ethereum blockchain platform.

Joseph Lubin, founder of ConsenSys, which has funded Civil with about $6 million (Photo courtesy of ConsenSys)

Based in a sticker and graffiti-covered brick building in East Williamsburg, ConsenSys was founded by the co-creator of Ethereum, Joseph Lubin, who is believed to be the single-largest holder of the Ethereum-based cryptocurrency, ether (ETH). In February, when ether was near its peak valuation, Forbes estimated his fortune at between $1 billion and $5 billion. But ether’s price has dropped 75% since then.

ConsenSys now employs more than 1,100 people around the world and has more than 50 portfolio companies, called “spokes” internally, all of which are paid for by ConsenSys. One of the main criticisms of ConsenSys, and of blockchain technology as a whole, is that it has yet to produce a useful application. With Civil, ConsenSys found a unique application, in journalism, to try out some of the asset-transfer features of blockchain technology. And, being in the journalism industry, it got a lot of press. (Editor’s note: the writer previously worked at OpenLaw, a ConsenSys portfolio company.)

“We didn’t get into this for any other reason than we think there’s an urgent problem facing the journalism world and, by extension, society, and we want to take a swing at something different,” Iles told The Bridge this week. “We’re emboldened by the community and the mostly positive reaction we’ve received.”

Last spring and summer, Civil went about funding startup newsrooms. The first one was called Popula, which produces articles about culture and politics, led by veteran reporter Maria Bustillos. Soon after came Sludge, a newsroom that tracks money in politics. At this point, at least 18 newsrooms run on the Civil platform. Fourteen of these newsrooms have been given cash grants by Civil, and all of them have received the rights to tokens.

Civil employs more than 20 people itself and the number of workers at its newsrooms reaches to 200. So far, Civil has raised $6 million from ConsenSys. In an interview, Iles declined to say when additional funding might come along, or its sources. The newsrooms are expected to produce their own revenue, in time, and some already have started to do so, from donations and other sources.

Problems With the Sale

Arguably the biggest story of the blockchain world in the last two years has been initial coin offerings (ICOs), also called token launches. In a token sale, a company creates a certain number of tokens and then sells those tokens around the world over the internet. The tokens can then be used to interact with that company’s product.

The more a company’s product is used by the public, the more valuable its token would become, the thinking goes. Since there are essentially no barriers on who can buy tokens, they open up a world of startup investing to everyday players, who otherwise face regulatory obstacles designed to protect small investors from getting burned by risky ventures.

In 2017, startup after startup raised major funding by offering tokens directly to the world. Filecoin, a company akin to Dropbox for the blockchain, raked in more than $250 million selling its token. A new blockchain protocol called Tezos raised more than $230 million. The list goes on. All this money raised the eyebrows of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which put a damper on ICOs in the U.S. when its chairman said in February that every ICO he’d seen looked like a security, meaning it would fall under the regulatory purview of the SEC.

Civil co-founders Julia Himmel, product designer, and Matt Coolidge, who focuses on brand strategy and communications (Photo courtesy of Civil)

It was in this environment that Civil chose to launch a token offering of its own. Its goal was to raise between $8 and $24 million through the sale of CVL. It would also comply with securities law, meaning that the token was not marketed as an investment, but rather as a useful key to be able to use for its intended purpose of supporting journalism.

The plan was to create 100 million CVL tokens. One third of them would be sold to the public, one third would be kept by Civil for distribution to its employees and future costs, and one third would be given to strategic partners, including the newsrooms on the platform. The tokens would be distributed to buyers in proportion to how much they pledged. Civil set a minimum threshold for the sale to be valid, similar to the way Kickstarter campaigns operate.

Prior to the sale, Civil hoped for a sale of between $8 and $24 million. At $24 million, each CVL token would come out to be worth about $0.70. At an $8 million raise, each token would be worth about $0.24.

Civil did not meet its minimum or anything close to it.

“This isn’t how we saw this going,” founder Iles wrote in a Medium post on the sale’s final day.

When the dust cleared, Civil received just $1.4 million. Since $1.1 of that came from Joe Lubin, the company by itself raised just $300,000 (this would have valued the CVL tokens at $0.008). The company has now returned the money to those who pledged.

Civil’s parent company, ConsenSys, has been quiet about the token sale. In the company’s monthly report for October, it mentioned only the number of Civil newsrooms and linked to one of the newsrooms’ podcasts about trusting yourself in startup-entrepreneurland.

When The Bridge asked ConsenSys’s chief strategy officer, Sam Cassatt, about the sale at a conference recently, the company’s marketing official accompanying him said it was time for lunch and all Civil questions would have to be directed to Civil.

According to Iles’ Medium post, the failed sale won’t put Civil under by any means. “We are backed by our investor, ConsenSys, and as a venture-backed, for-profit company, will likely continue to fund operations via equity investment until such time that we can sustain ourselves via commercial activity,” he wrote.

One of the problems that occurred during the sale was the difficulty users faced in participating. According to the NiemanLab at Harvard, there were 44 steps that needed to be taken to buy a CVL coin, due to the cumbersome nature of buying cryptocurrency and the steps necessary to have Civil’s bases covered with the SEC.

“You were required to study for and pass a test to show you understood Civil and cryptocurrency,” recalled Ethan Zuckerman, director of the Center for Civic Media at the MIT Media Lab. He participated in the token sale, attempting to buy about $70 worth of CVL because he thought it was an interesting new direction for journalism and he wanted to be a part of it, he said.

Said Iles in an interview: “This is what we signed up for and we’re not out of the first inning yet” (Photo courtesy of Civil)

“They pointed you towards various documents, videos and written documents. The quiz asks you what’s the difference between a hot wallet and a cold wallet and what it means if you don’t have sufficient gas to complete a transaction. I believe it was like half a dozen questions. A number of people mentioned that they’d taken it and failed it. It was not a gimme quiz.”

Zuckerman himself got stuck in the process but happens to be friends with Vivian Schiller, the chairman of the Civil Foundation, who helped get his purchase to go through.

Was CVL just too much of an awkward, in-between device? “The idea of this feature is that it would kind of undercut an argument that it’s a security because no one would purchase with a view to an investment if you have to actually use it,” explained a securities lawyer working in the blockchain space, who asked not to be named. “This is a new model [for ICOs]. Was it the structuring or the product itself? It’s really hard to raise $8 million. And it had to be from consumers. No big funds are going to want to go in. So now you’re at a place where it’s not really an investment and [as a pre-product sale] consumers aren’t really incentivized to buy it either. It’s a tough space to be in.”

“I think they overhyped demand and then smothered demand by making it really hard to buy [the tokens],” said CJR’s Ingram. “That might have been by design to keep out speculators, but I think it also kept out supporters. It was hugely overambitious and probably over-engineered. Eventually people just turn off. If you can give them a hundred bucks, great, but if you have to jump over these barriers …,” he said. “They at least started, or helped start, a bunch of newsrooms. That’s gotta be worth something. I think their heart’s in the right place.”

Not everyone agrees with that.

Internal Problems

“What is Civil doing that it offers to the world? And why is there a token? What does that do that a dollar can’t do? This is a whole stinking pile of shit,” said Daniel Sieberg, one of the earliest hires at Civil, who joined with a title of co-founder in November 2017. He was fired from the company in July of this year.

Sieberg, who had been a correspondent for CNN and CBS News and an executive at Google, said he became disillusioned by the product Civil was building over the summer—and by the constant delays.

“The doublespeak, the Orwellian-ness of this. Coming soon? What’s coming soon? I don’t know how anyone can look at this and think it was anything other than a massive failure or a massive fraud,” he said. “If I had a bitcoin for every time I heard ‘Coming soon,’ I would actually be a millionaire.”

In an interview, Iles and cofounder Matthew Coolidge bridled at the allegation of any deception.

“To suggest that Civil is a fraud is borderline slanderous,” Coolidge said. “We’re not. We’re 24 people that are working our tails off to try to make this a reality. This is not any kind of get-rich-quick scheme and there are warts and all, and obviously there have been plenty of warts. But I draw the line at fraudulence.”

A scene from this year’s Ethereal Summit, where blockchain aficionados gather to talk about the technology’s potential uses (Photo by Steve Koepp)

“I strongly refute questioning the integrity of the project,” added Iles. “You could say ‘I don’t think this is a good idea’ and ‘I don’t think someone should pay for this’ but I do not think Civil is a fraud.”

Another angry former employee spoke up this week. Jay Cassano worked at the Civil newsroom Sludge until this month. He told The Bridge that he was paid in part in promises of CVL tokens, which he said Civil brass led him to believe would be worth around $0.75 each.

When he joined the company, in March, Cassano was offered several packages with various proportions of money and future CVL tokens. Cassano said he was pressured to take a package with a higher percentage of tokens, which meant he made very little money for the first four months he was there, during which time he took on debt to get by.

“At that point, Civil was saying that the token sale would happen in May and the platform would launch in June,” Cassano said this week. “After a few months Civil realized they were completely out of their depth and they were trying to build a new [content-management system] from scratch and decided they would launch all their publications on WordPress and that the technology they would deliver would actually be WordPress plug-ins.” (WordPress is the workhorse of content-management systems, running tens of millions of websites, including The Bridge.)

“That was sort of the first alarm bell and some reporters were concerned by that because it showed that there wasn’t going to be that much technology differentiation,” said Cassano, “and it also showed a level of incompetence that they spent all this time building a platform they threw out for this WordPress. They kept pushing things back and still are.”

Cassano acknowledged that after his first five months on the job under his initial contract, he signed a new, more conventional agreement, in which he got paid fully in dollars at a competitive salary.

His boss at Sludge, David Moore, disputes the idea that Civil implied the tokens would be worth a certain value.

“The newsrooms had good communications and clarity from Civil that this was a new consumer token and it would come with all these restrictions,” Moore explained. “The token had so many regulations around it … that we weren’t expecting the token to be dollar-valued initially.”

“It’s hard to describe this without sounding bearish,” Moore said, “but we were expecting our newsroom to be primarily sustained through fiat [currency] donations, collected through Stripe. I can be quite direct and forthright that there were no representations from Civil of a price floor. We knew the token would be volatile and could be valued in the markets at low rates.”

Another reporter, who remains employed in a Civil newsroom and asked not to be named, noted that salaries are on the whole quite good for reporters at Civil, but agreed that the company gave a rosy impression about the sale.

“My recollection is on group calls or conference calls that there was the impression that the tokens would be [worth] around 75 cents or a dollar or even up to $3 or $4,” the Civil journalist said.

Another journalist, also still at a Civil newsroom, agreed there was talk of the tokens being worth in the $0.75 to $1 range, but said that the estimates were based on hope, not on dishonesty.

“Startup publications are always in danger of folding, that’s kind of the caveat emptor of this industry. They have some money here and are trying something and paying you to write. I didn’t take this job thinking these tokens were something I could count on being worth a lot,” the reporter said.

What Is Civil’s Future?

Iles said Civil won’t do another token sale. “We’re not quite ready to speak in much detail about what comes next. What we are definitely not doing is what we did before,” he said. “Tokens are very much a part of our future. What we’re not doing is a token sale in the kind we did last time, with a soft cap and a hard cap.”

People remain interested.

“I was and I remain very intrigued by it,” said the Newmark school’s Bartlett. “I think the blockchain technology offers some really interesting opportunities for journalism, so I like that there are people trying to experiment with that… I think they’ve attracted really smart people, so there’s a lot of talent in their content production. Those are good people with good ideas, so to see capital being used for those purposes makes me happy.”

At Sludge, Moore’s seed funding from Civil is set to end in March, a year after he brought the newsroom online. He said his team will continue to raise money in other ways to keep it running, including crowdfunding, through partnerships and collaborations with other publications, even from an eventual token sale.

“There’s going to have to be a new plan for getting these tokens out into people’s hands and there’s more to come on that,” he said. “We’ll continue to build our base of donors and be a pioneer so that when people can touch the tokens on our website they will hopefully see that this is a different experience and it gives them a say on the governance of the platform, it gives them a say on the ethics of the newsroom. When more people have CVL tokens in a wallet and can conduct transactions on the site, we think we can generate more partnerships with other newsrooms. It will be different than just setting up a WordPress site, setting up a Mailchimp and setting up a Patreon.”

Iles says a new plan is coming soon.

“This is what we signed up for and we’re not out of the first inning yet. If you think this is stressful, wait till we get out of this and start taking on the incumbents. We’re not even born yet.”

Brooklyn Finally Gets a Japanese Market of Its Own

Saying that Brooklyn is a food destination is, at the end of 2018, a full-on platitude. Yet, despite the worldwide culinary experience the borough has been offering, Japanese cuisine has had a shortage of representation. At least until now.

Since mid November, the 20,000-sq.-ft. Japan Village in Sunset Park’s Industry City has been in soft-opening mode (a grand-opening date remains to be announced), with offerings ranging from an outpost of Manhattan’s Japanese supermarket Sunrise Mart to back-alley-style stalls that celebrate the wide variety of Japanese comfort food ranging from ramen to okonomiyaki, the decadent savory pancakes. Opening soon are an izakaya-style pub, a Japanese liquor store and, eventually, a dry-goods store offering pottery, stationery and cosmetics.

“We first started looking at this concept two years ago,” said Jim Somoza, Industry City’s director of development. “We realized that there was no Japanese market in Brooklyn at all.” He recalls that, when he was living in Manhattan before relocating to Brooklyn, he frequently visited Katagiri, a storied Japanese grocery.

“I moved to Brooklyn and I realized Japanese food really resonates with people because it’s an exotic Asian food that is also accessible and healthy.” It’s the healthy component that, he believes, sets Japanese food apart from what Americans normally associate with Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean fare.

Chefs at work at one of the marketplace’s food stalls, which focus on street-and-comfort foods (Photo by Angelica Frey)

Looking for a partner to develop the idea, Industry City reached out to Sunrise Mart and Katagiri, getting an enthusiastic response from Tony Yoshida, whose family owns several businesses including Sunrise Market and the Michelin-starred Kyo Ya. Somoza recalls a lot of “What if we did this?” and “What if we did that?” as the two parties planned the new Brooklyn marketplace. “It’s the best when that happens,” said Somoza, “because I am not just trying to sell them Industry City, and they’re not just trying to sell me on the concept. We both married right away.”

The food stalls offer a gamut of Japanese styles including bento, ramen, rice bowls, Japanese appetizers and Teppanyaki griddle-cooked steak and lobster. The stalls share an aesthetic that, thankfully, eschews a Disneyland-like idea of a Japanese food hall. In other words, they’re clean but not culturally sterile.

The Sunrise Mart grocery story is filled with locally hard-to-fine items (Photo by Angelica Frey)

The grocery-store component of the marketplace contains a selection of locally hard-to-find items including the green-tea matcha KitKat candy bar; Milky yogurt in a collagen-and-honey flavor; and Tamari Shoyu Sekigahara soy sauce, containing licorice root. The forthcoming dry-goods store will also feature Japanese cosmetics, which tend to offer high quality and moderate prices. “We don’t want to lose the crafts, the small-scale producers, and we can give them an American audience,” Yoshida told the New York Times.

Industry City’s Somoza wants the 6-million-sq.-ft. complex to be a hub for cuisines from all around the world, where people can stroll for a whole afternoon and take a bite at one place, then one at another. Japan Village joins the ranks of such vendors as Yaso Tangbao (Shanghai-style street food), Bangkok B.A.R. (Thai), Ejen (Korean) and Table 87 (pizza). Garnering enough foot traffic does not seem to be an issue: 7,500 people work at Industry City, up from 2,000 four years ago and heading for an estimated 15,000 in the next two years.

On the weekends, Industry City is evolving into a leisure-time destination. “It’s a place for people to come and hang out, especially in the wintertime, because it’s a lot of heated, big space,” said Somoza. “People can come with their kids, who can run around without breaking anything, and you can try all the cuisines.” An estimated 15,000 people per weekend have bought into that proposition. Adventuresome tourists have too, drawn by the post-industrial vibe of the giant buildings, mostly constructed in the early 20th century. “People love seeing buildings like this that have an authentic industrial past being reused for things like this,” said Samoza.

Cafe Japon sells cakes and breads, as well as a variety of Japanese teas and coffee drinks (Photo courtesy of Japan Village)

Shop Brooklyn: Your Ultimate Local Holiday Gift Guide

Yes, Amazon is putting down roots in New York City, but that doesn’t mean it qualifies as a place to shop local. Better to keep your holiday business in Brooklyn, if you can, where we’re surrounded by makers, designers and creative shopkeepers. To guide your holiday shopping, we’ve curated a diverse selection of gift ideas (with links to buy). All these items were made, designed or stocked here by local merchants.

You can also shop Brooklyn at the site IntoBrooklyn, consult the retail guide at Explore Brooklyn, or check out the gift guide of one of our Brooklyn colleagues. Found any other great Brooklyn products people should know about? Please share in comments. Happy holidays!

For Your Green-thumbed Mom

Hanging plants may be all the rage, but the hanging apparatus often leaves something to be desired. Not so with this 30-inch leather beaut, handmade by a husband-and-wife team. Holds a four-inch pot. $60 at Polt, 390 Van Brunt St.

For Your Sneakerhead Teen

Reebok recently released a collab with Pyer Moss’s founder, the Brooklyn streetwear darling Kerby Jean-Raymond. One standout: This boxy, 100% cotton “As USA as U” men’s tee. $90 at Reebok.com.

For Literary Types

The New York Times called the Russian-born Brooklynite’s first novel, published in July, “artful and autumnal”: “He writes incisively about … how it is easier to fight for your principles than live up to them.” A Terrible Country by Keith Gessen, $26 at Books Are Magic, 225 Smith St.

For Your Caffeine-addict Brother

Brooklyn coffee roasters Anu Menon and Suyog Mody select four outstanding single-origin whole-bean coffees, each with a different flavor profile (balanced, bold, classic, and fruity). Countries of origin may vary. Four 4-oz. packages in one gift box. World Explorers Coffee Sampler, $32 from Driftaway Coffee at Uncommon Goods.

For Women Who Love Jewelry

These simple handmade earrings measure 2.5 inches in diameter and are handmade in Brooklyn. Disk Hoops Brass by Lila Rice, $198 at Swords-Smith, 98 S. 4th St., Williamsburg.

For Fidgeters Who Are So Over Fidget Spinners

Wobbals, pronounced wob-bles, are exactly what they sound like. Half of each ball is solid brass; the other half solid wood. Set of three, $60 at Richard Clarkson Studio.

For Typeface Enthusiasts

Brooklyn artist Paul Smotrys makes these “Empire’ freestanding aluminum letters and numbers to order. Four inches tall, $10 each at Gauge NYC via Etsy.

For Fashion-forward Women

Perhaps the perfect ankle boot: black nappa leather, pointed (but not too) toe, walkable cylinder-shaped mid-heel in classic red. Designed by Brooklyn-based Silvia Avanzi and made in Italy. Gray Matters Monika Boot in Nero Ruggine, $595.

For Your Uncle With Lower-back Problems

Backed in linen and handmade in Flatbush from genuine African mud cloth, these cream-and-black “Nina” pillow covers have an unexpectedly modern vibe, $30 from Stitched by Grace at Coterie Brooklyn.

For Your Favorite Bathroom

Deep-six the plastic bathroom cups for these stoneware versions, dimpled for a good grip. Hand-thrown in Brooklyn by Andrea Juda and Kristin Mueller. Dimple Tumbler, $20, from Slip Clayware via Etsy.

For Your Trump-hating Brother

This lefty answer to the MAGA hat was designed by Williamsburg artist/writer/activist Celine Semaan and made in USA. The “No” baseball cap, “unlike the other red hats we have seen too many of,” $40 at the Slow Factory.

For Your Aunt Who Needs a Stress Reliever

Everything she’ll need to knit a super cute Fair Isle-style wool hat, packaged in a gift box. Lucerne Knitting Kit, $40, from Brooklyn Tweed.

For Your Sister Who Wants You to Bring the Hors d’Oeuvres

You’ll get three to four artisanal cheeses, three accompaniments, and crackers. Petite cheese platter, $75, from Belle Cheese at City Point’s DeKalb Market Hall, 445 Albee Square West. Place your order at the store in Downtown Brooklyn or email info@bellecheese.com.

For a Whimsy-loving Sort

Founded by South African-born designer Jann Cheifitz, Lucky Fish makes these organic, lavender-scented sculpted soaps in Sunset Park’s Industry City. Hand soap, $16, from Lucky Fish.

For the Spouse Who Keeps Throwing Dry Cleaning on the Sofa and Leaving It There

Manufactured in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, this eye-catching hook is glamorous enough to affix to the outside of your closet. Lucite and brass eight-inch projection hook, $70 by Lux Holdups via Etsy.

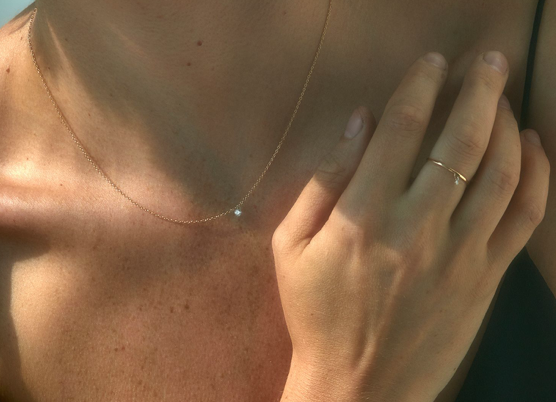

For the Minimalist

A 3mm white diamond clings to a solid 14k yellow-gold chain, adjustable from 15 to 17 inches, by a platinum ring drilled into the stone. Diamond Pinprick Necklace, $388, from Catbird, 219 Bedford Ave., Williamsburg.

For Your Friend Who Has Everything

Korea-born Brooklyn artist KangHee Kim uses mirrored images of bricks and custom-shaped pieces to create two different puzzles that can be completed separately or together. Puzzle in Puzzle, $20, from Areaware, 267 Irving Ave.

Grit Meets Glam: the Water Tower Bar Is Peak Brooklyn

While Brooklyn has upscaled radically over the years, its rugged water towers have stuck around, still capably performing their original function and now serving as a reminder of the borough’s industrial past. The beloved icon adorns T-shirts, tote bags and touristy souvenirs.

Now the water-tower motif has been cast in another role: as a nightlife peak experience. Opening last night, The Water Tower bar atop the Williamsburg Hotel is a glam, boozy, high-end moneymaker. The hotel’s third onsite watering hole is exactly what it sounds like: a speakeasy-style boîte housed high above the hotel, in a circular structure with a pointy top, shaped like an urban water tank.

Inside, instead of tens of thousands of gallons of potable water from a reservoir upstate, there’s a tall, cavernous 45-seat lounge with dangling bubble-esque lighting. It feels a little like stepping into a giant glass of chilled champagne—for a price.

The bar, open from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., segues into a nightclub vibe

The Water Tower bar’s cocktails are $22 and higher, dreamed up by mixologist Rael Petit (formerly of The Standard), including the strong-as-medicine, CBD-oil infused Purple Rain, served in a gilded, filigreed coupe; the lighter yuzu-imbued Les Gnomes, housed in a copper gnome-shaped vessel and tasting like a huge bite of an aromatic herb garden, but in the best way possible; and the $150 Heart of Gold, a play on the Negroni, made with white truffle-infused Aperol and a truffle shaving.

All of these concoctions are made behind a teensy, triangular white-marble bar and delivered by genial servers dressed in black turtlenecks, black skinny jeans, and stacked-heel boots. Bottle service starts at $500, and executive chef Nic Caicedo’s menu of small plates includes a $525 caviar tasting, white-truffle grilled cheese nestled in a rough-hewn wooden bowl, and a fanciful seasonal seafood tower—ahem, “Seafood Plateau.”

Right in step with the upscale selling points, the glowing industrial structure, with its floor-to-ceiling glass windows and glittery Manhattan skyline views, makes the city’s utilitarian, untreated-wood and stainless-steel water towers look downright provincial. As for how bar-goers get up there, climbing rickety exterior stairs isn’t a concern. Visitors glide up to the bar in a “VIP elevator,” bypassing the hotel-room floors, as with the nearby Westlight bar at the William Vale.

Among the offerings from executive chef Nic Caicedo is a “seafood plateau”

But if you fancy a breath of fresh air, a better view of the Empire State Building, or a smoke, a concrete walkway surrounds the cylindrical building, with a railing designed with safety in mind. “The exterior steel and wood structure of The Water Tower stands on top of the hotel’s brick building as a reminder of the industrial past of New York City,” according to a statement from the hotel.

Inside, velvet couches in royal blue, lime green, and tan line the perimeter of the brass-and-walnut interior space, furnished with coffee tables and plush armchairs to create the cozy vibe envisioned by London-based design firm Michaelis Boyd Studio. However, the panoramic views have some odd visual competition: Giant murals on the walls bear kitschy, refrigerator-magnet-style pop images of retro housewives—and, incongruously, Wonder Woman—alongside phrases like “Dear Brain … Please Shut Up!” and “If it’s the thought that counts, I should probably be in jail.”

Hotel management says the signs are “a nod to the hand-painted ads that dot the streets of the neighborhood.” In reality, they’re six-foot-tall versions of sardonic quotes that your frenemies from high school post on Facebook—plus a quip from Jay McInerney way up in the right-hand corner for literary types—but the wall is indisputably a magnet for social-media addicts. Yesterday, guests were panning the space with their smartphones, ideal video fodder for Instagram Stories.

The towering ceilings contrast with a tiny, white-marble bar

International DJs figure prominently into the concept, which will veer closer to a high-key nightclub in the wee hours. Late last night, nostalgia-fueled mashups from artists like Aretha Franklin, Big Hooch, and Stevie Wonder pumped through the space (there are speakers on the outside platform, too, so the party doesn’t stop), courtesy of DJ: Leo Tebele’s team. The bar is open from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. Wednesday through Sunday.

To ensure you’ll get a seat, you’ll need to make a reservation, which are currently free (a/k/a no bottle-service purchase necessary), by emailing watertower@thewilliamsburghotel.com. Walk-ins are welcome, but considering the bar’s limited capacity, would-be revelers could be waiting in the lobby for a while.

The opening of The Water Tower is a crowning touch for the hotel, which opened to guests in January 2017 and debuted its rooftop pool this summer. “We started thinking about The Water Tower when we broke ground for The Williamsburg Hotel a few years back,” hotel management stated. “The full project came to fruition in 2018, but it was always a part of the plan for the hotel.” The Williamsburg has joined a wave of swanky new hotels across a northern arc of the borough, many combining industrial elements with an urbane vibe, as well as a stylish new breed of cocktail bars.

The bar and hotel under construction in May 2017 (Photo by Steve Koepp)

It would be easy to frame the theme-drenched Water Tower bar as a parody of Brooklyn’s recent makeover, yet another example of what gentrification has wrought. That’s an understandable take. But it might also be a cheap shot.

“When I heard about it and saw it from afar, I thought it was another great tribute to the water-tank industry and to New York, like the stained-glass tank off the BQE,” says Andrew Rosenwach, of the Rosenwach Group, formerly known as the Rosenwach Tank Co., a fourth-generation outfit that has built and maintained New York City water towers since the late 1890s. “You know what our motto is: Tanks make people happy, and this new restaurant looks like a fun spark that does give applause to the water tanks.”

In fact, Rosenwach liked the idea of The Water Tower bar so much that the company tried to book its annual Christmas party there, but the tank wasn’t big enough to accommodate its 150 employees.

Coincidentally, the Rosenwach Tank Co. used to reside catty-corner from the Williamsburg Hotel, on North 9th Street—that is, until around the time a group of “hipsters” reportedly set it ablaze while shooting off illegal roman candles in 2009. The site is now occupied by The Hoxton hotel, which opened in September; Rosenwach’s newest fabrication facility is located in Somerset, N.J.

“But we’re always, in our hearts, Brooklyn,” Rosenwach says. “In fact, with the new location, we call it the Brooklyn shop.”

Amazon Next Door: What Does It Mean for Brooklyn?

Since Amazon announced that half of its second headquarters is coming to Long Island City—with the other half landing in Crystal City, Va.—opinions on the development ranging from jubilant to outraged have flooded the zeitgeist. In Queens, the news has raised concerns about everything from the state’s generous tax incentives to rising housing costs to overcrowded transit systems.

As early as next year, Amazon will occupy up to 500,000 sq. ft. of office space in the 50-story tower at One Court Square in Long Island City, while working to develop 4 million sq. ft. of commercial space on the nearby waterfront over the next decade, and possibly much more in the years beyond, according to the New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYCEDC).

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo, often at odds, showed rare agreeability in cutting the deal. “We’re building a New York that’s attracting the industries of tomorrow,” read a tweet from the governor. “My thanks to @NYCMayor and our partners in the city for their help in this transformative investment in Queens.”

But what the mayor and governor hailed as a blessing was seen as a burden by many local officials, who felt the deal was imposed on them without their consent. “The community’s response? Outrage,” read a tweet from newly elected U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who will represent sections of the borough that abut Long Island City.

But what of Brooklyn?

Looking along 44th Drive in Long Island City, Queens, toward the towers of midtown Manhattan (Photo by Mark Lennihan/AP)

Like 238 other cities scattered across North America, Brooklyn put in its own bid last year for the headquarters project, known as HQ2. In an open letter to Amazon, Borough President Eric Adams advertised Brooklyn as though it were an independent municipality—“America’s fourth- (and soon-to-be third-) largest city”—while touting the area’s tech-centric universities, skilled workers, thriving neighborhoods and abundant mass transit.

Given the borough’s impassioned pitch, some Brooklynites may view Amazon’s choice of Long Island City as a snub. But with Amazon pouring an estimated $2.5 billion into a neighborhood just across Newtown Creek, the company’s arrival in Queens is sure to have an outsized impact on Kings County as well.

Potentially, here’s how:

The Prospect of New Jobs

The NYCEDC says that with Amazon’s second headquarters coming to Long Island City, the company “will draw from the diverse and talented workforce” in the area to fill a minimum of 25,000 new jobs by 2029. Up to 40,000 jobs are expected to be created by 2034.

“With an average salary of $150,000 per year for 25,000 new jobs Amazon is creating in Queens, economic opportunity and investment will flourish for the entire region,” Cuomo said in the NYCEDC’s press release. “Amazon understands that New York has everything the company needs to continue its growth.”

Regina Myer, president of Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, a collective of local leaders committed to the neighborhood’s prosperity, echoed that sentiment in an interview with The Bridge after the announcement. Though she’d hoped HQ2 would have landed in Brooklyn, Myer stressed that Amazon’s decision to build anywhere in the five boroughs is “a net positive” and “great news for all of us.”

“I really think that having this kind of job growth in the city of New York is exactly what we need,” she said. “Amazon made the decision to come to New York City … because they knew they could find talent, and to me that’s why this is such an important move for New York.”

Myer added that she’s certain there will be “some fantastic spinoff” in the form of “other tech companies moving to either New York City, or, obviously, my first choice would be Brooklyn.” She observed that members in the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership and officials in the area have been “spending so much time building on the strengths” of nearby tech schools like the NYU Tandon School of Engineering and City Tech, part of the Brooklyn Tech Triangle that includes innovative companies and startup incubators in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Dumbo.

Amazon workers in its campus in Seattle, where its employs more than 40,000 people (Amazon photo)

“We are excited about Amazon’s decision to co-locate its new headquarters in New York City,” said Jelena Kovačević, dean of NYU Tandon, in an email to The Bridge. “While the company’s needs in such areas as computer science, AI, cybersecurity and tech management will surely be a boon to the school and our students—providing internships and employment opportunities—it will also help accelerate the existing growth of the Brooklyn Innovation Coastline. … While NYU draws students from all over the U.S. and world, most stay on and work here in New York.”

But what about Brooklynites without engineering degrees? The potential ripple effects on other industries have yet to be charted, though Amazon says that in Seattle, 53,000 additional jobs were created as a result of the company’s investments there, besides its direct payroll. In New York City, the construction trade may be the first to benefit.

The building of the HQ2 complex is expected to create an average of 1,300 direct construction jobs annually through 2033, according to the NYCEDC. Gary LaBarbera, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, said in the press release: “We look forward to working closely with Amazon and the community to ensure that the project includes good middle-class construction jobs with benefits and high-quality permanent jobs.”

Amazon’s HQ2 is estimated to create more than 107,000 total direct and indirect jobs, as well as over $14 billion in new tax revenue for the state and a net of $13.5 billion in city tax revenue, according to the NYCEDC. The city and state expect an overall 9:1 return on their investment from the tax incentives being offered.

Big Development, Higher Costs

The arrival of Amazon’s campus is likely to supercharge the residential-development boom already underway in Long Island City, as well as the neighborhoods to the south in Greenpoint and Williamsburg. According to a report from Localize Labs, which analyzed data from the city’s Department of Buildings for the year beginning July 1, 2017, Long Island City saw 1,436 new housing units approved by the DOB, the most of any neighborhood in the five boroughs. Williamsburg ranked ninth on that list with 677.

Even more is in the pipeline. Long Island City also had the highest number of apartments with permits awaiting approval during that time, with 2,597. Greenpoint came in second, with applications filed for 1,493 units. So in terms of available space, if there’s any area in the city that’s geared up to house an influx of new Amazonian workers, it’s Southwest Queens and Northwest Brooklyn.

Just to the south of Long Island City, along a half-mile stretch of the East River waterfront, the Greenpoint Landing development is expected to include 5,500 residential units within a decade. Just to the south of that future skyline, plans are underway for a 40-story, mixed-use tower at 18 India St., just across the street from The Greenpoint, a just-completed residential tower of the same height. The 18 India St. building is expected to include about 470 new units, some of which will be deemed affordable housing. An 11-story building on the rise at 30 Kent Street will house 80 units, to name a few of the many new developments in the neighborhood.

Amazon’s complex in Seattle includes 33 buildings with more than 8 million sq. ft. of floor space (Photo by Jordan Stead/Amazon)

Plenty of new apartments, but at what prices? The demand from well-paid Amazon employees is likely to reignite the rise of rents and residential-property values in Brooklyn, at least in the vicinity of the new campus. Kara Dusenbury, director of sales at the Williamsburg-based Brick & Mortar real-estate firm, told The Bridge that asking prices at new condo developments in Greenpoint are “a little under $2,000 a square foot.” She called that figure “crazy.” “I remember along McCarren Park, in 2007, the asking price was $600,” Dusenbury said. “This is three times as much, what, in 11 years?”

Will Brooklyn become the next Seattle, overwhelmed by Amazon’s presence? “When Amazon first moved in, Seattle wasn’t even near the top of America’s priciest housing markets. Today, at a median home price of $739,600 and median rent of $2,479, it’s now the third-most expensive housing market in the country,” wrote real-estate reporter Aly J. Yale in a Forbes article. But New York City is a far bigger place, “one of few cities that can best absorb HQ2 with minimal disruptive impact.”

Transit Innovation and Expansion?