Why That New Chain Store Just Landed on Your Block

They're arriving in Brooklyn faster than in any other borough. Can mom-and-pop shops survive in a land of giants?

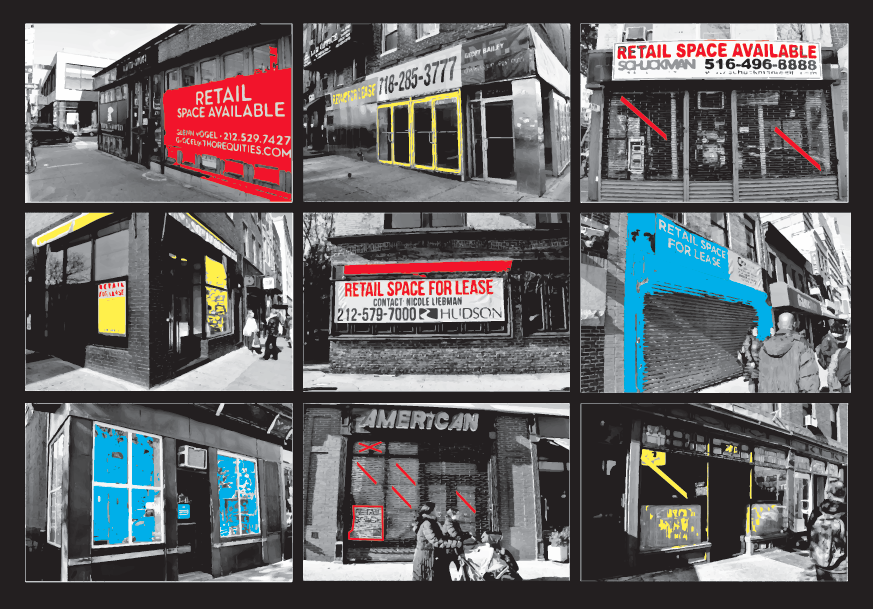

While small business has been under strain because of rising rents, an increasing number of chain stores have taken their places (Illustration by Heather Jones. Photos by Arden Phillips)

It’s an invasion of the store snatchers. Where mom-and-pop shops once beckoned in Brooklyn, the storefronts are now adorned with the signs of chains you see everywhere else: Dunkin’ Donuts, MetroPCS, McDonald’s, CVS, Payless, Gamestop and Starbucks, among dozens of others. While the rest of the country is sounding the death knell for malls, Brooklyn is booming with the shops that are typically found in them.

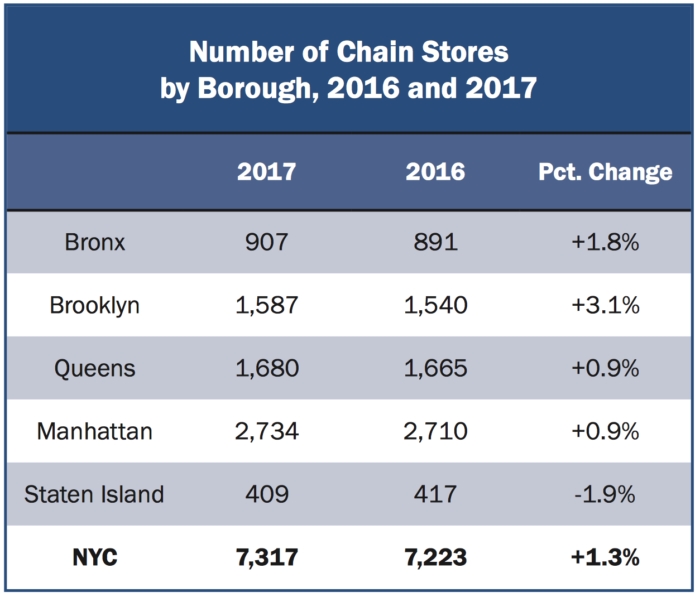

Last year, Brooklyn saw the biggest percentage increase in the number of chain stores of all the city’s boroughs, with 1,587 locations, a 3.1% increase from the previous year, according to a December report from Center for an Urban Future. The greatest concentration of these stores is in zip code 11201 (Brooklyn Heights/Downtown Brooklyn), which has 145 national retailer locations including City Point’s Target, Fulton Street’s H&M, and Sephora on Joralemon Street. Dunkin’ Donuts has the largest number of chain locations in Brooklyn, with 139, followed closely by prepaid wireless service MetroPCS, with 138.

While it’s happening most quickly in prospering Brooklyn, the trend is epic and citywide. In the past ten years, since Center for an Urban Future began issuing the report, coffee chains like Starbucks and Dunkin’ Donuts have expanded 65% across the city, while fast-casual restaurant chains like Chipotle and Le Pain Quotidien have more than doubled. National-brand department stores have increased 144%.

Dunkin’ Donuts has been the most ubiquitous national brand in the borough, with 139 shops

Brooklyn is gaining share of the city’s chain-store share, with 22%, up two percentage points from last year, while Manhattan is losing share, with 37%, down two points. All of which to say is, in some places, the boroughs are looking more like one another (and the rest of the country)–and the trend doesn’t seem likely to stop.

“Retailers are kind of like a herd of sheep,” says Tim King, managing partner of CPEX Real Estate, who helped bring Bed Bath & Beyond and its three sister companies to the Liberty View shopping complex in Sunset Park. “Nobody wants to be the first sheep through the gate. But once the herd starts moving in that direction, you get followers.”

The herd has definitely arrived in Brooklyn. And to some, it feels like a turning point. On the one hand, Brooklynites now have increased access to the discounts and variety that were previously available only in Manhattan or nearby suburbs. On the other hand, the borough is losing a colorful slice of its street and neighborhood culture. The tension is palpable.

“People are concerned when any neighborhood that you go to in New York City not only looks like any other neighborhood, but looks like anywhere else in the country,” says Christian González-Rivera, a senior researcher at the Center for an Urban Future. “You might be in Iowa or you might be in Brooklyn Heights, and you’ll see the same stores selling the same products. We like to think of ourselves as having the kind of creative foment in this city that can produce interesting small businesses, and many New Yorkers say they’d rather shop in locally owned small businesses that sell unique products to unique people.”

The Mall-ification of Brooklyn

Fifteen years ago, if you moved to New York City without a stick of furniture, taking a bus to Elizabeth, N.J. for an obligatory trip to Ikea was a (mostly miserable) rite of passage. But in 2008, Ikea became something of a big-box pioneer, opening its only city location in Red Hook, where you can now take a Lyft to pick up your Billy bookcase. Other big-box stores have followed.

(Chart courtesy of Center for an Urban Future)

Those national chains help address retail-shopping “leakage” in a borough that is still underserved by available stores; Brooklyn has 32 sq. ft. of retail space per person, compared to a national average of 47 sq. ft., according to CPEX’s 2017 Brooklyn Retail Report. The Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce estimates that as recently as 2015, the borough was losing $5.8 billion in retail revenue as residents left the borough to shop elsewhere.

“The supply of retail opportunities didn’t even come within the ballpark of the demand,” says Andrew Hoan, the president and CEO of the Brooklyn Chamber. “[When chains move in], people say ‘Oh, there goes the neighborhood,’ but it’s actually a good thing because they may have otherwise gone to Nassau County or Jersey to spend those dollars.”

Since the early 2000s, big-box chains have been on the march from the already saturated suburbs into cities, with chains like Target, TJ Maxx and Bed Bath & Beyond “aggressively” expanding in urban areas, according to the 72-page Planning for Retail Diversity report from the New York City Council.

As a result, neighborhoods from Sunset Park to East New York to Downtown Brooklyn are home to many of the same national businesses familiar to anyone who’s driven on an Interstate anywhere in America. East New York has both the Gateway Center (opened in 2002) and the Gateway Center II (opened in 2014). Downtown Brooklyn has the Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal malls (opened in 2004), as well as City Point (opened in 2015).

The prepaid wireless service MetroPCS is another aggressive arrival in Brooklyn, with 138 stores

The hyper-development in downtown Brooklyn is the result of the Downtown Brooklyn Plan, adopted in 2004, which changed the zoning to allow for more high-rise towers with lower-floor retail. The preference for “credit tenants,” typically stable, large businesses like banks or national retailers that are most likely to pay the rent each month, have given the area an open-air mall feel.

Being a chain doesn’t guarantee success, of course: some chains, especially those that compete most directly with online shopping, are struggling. There are half as many electronics retailers in the city as there were ten years ago, and office-supply stores and shoe retailers are in retreat (definitely blame Zappos). Chain pharmacies have also started contracting following the Duane Reade/Walgreens merger, according to the Center for an Urban Future.

But generally, the arrival of chain stores in a neighborhood is a sign that real-estate prices are about to go up. This can be a boon, or a burden, to local businesses.

The Gateway Effect

To demonstrate how small businesses can ride the draft of chain stores, the Chamber of Commerce suggested The Bridge speak with Andrew Walcott, an East New York native who opened his upscale Caribbean/soul food restaurant, Fusion East, directly across the street from the Gateway Center. He saw economic value being added to the neighborhood because of the mall. More Brooklynites were streaming into the neighborhood to shop there, but its food options were lacking.

“At the mall, they have plenty of options, but nothing that people in the area, which is prominently Caribbean and black, grew up on,” says Walcott. Area residents looking for something familiar, and more upscale, had nowhere to go locally, he says, and would travel to Downtown Brooklyn or even Harlem for date-night experiences. “I saw a need in the community, and I saw an opportunity.”

In 2015, he took over a failed restaurant on Elton Street that already had a kitchen and a disability-access bathroom, helping save on building costs. Still, the first year was a struggle. A road leaving the mall that would run right past his storefront was not yet open, and he felt he was losing business and visibility. With help from the Brooklyn Chamber and the Department of Transportation, the road opened in November 2016, and Walcott saw an immediate 30% to 40% increase in business, he says. “A bunch of different local politicians really helped to get that road in so we could participate in the economic growth going on inside the mall,” Walcott says. “Shoppers can drive past, walk past. Many of our customers park in the mall and walk back to the restaurant, which helps a lot.”

Walcott says he isn’t currently concerned about rising rents. He has a ten-year lease, and notes that he’s an attorney and CPA (as well as an Air Force veteran) who negotiated his lease to “avoid being priced out of my own community.”

A Wave of Vacancies

Being priced out of your own community, of course, is happening all over the city, as chronicled by blogs like Vanishing New York and advocacy groups like TakeBackNYC (which estimates that 1,000 to 1,200 small businesses close each month due to large rent increases). For every success story like Fusion East, there is a beloved local institution forced out as prices rise. Red Hook’s dive bar Bait & Tackle and restaurant Hope & Anchor are two of the latest casualties. The problem of so-called “high-rent blight” and hyper gentrification has been well documented. A quick stroll on Court or Smith streets in Cobble Hill suggests what types of shops can afford soaring rents: national chains like Lululemon, Rag & Bone, and Benefit Cosmetics. And don’t forget the increasingly ubiquitous Dunkin’.

(Illustration by Heather Jones)

“By and large, residents of Brooklyn do a really good job of supporting local businesses,” says Dan Marks, a partner at Brooklyn commercial real-estate firm TerraCRG. “What you’re finding is not that residents are shopping exclusively at national retailers, it’s that landlords are seeing what’s happening around them and saying, ‘Hey, if Whole Foods is here, that means my rent can go up.’ Landlords are charging rents when the markets are not quite there yet. You start to see a wave of vacancies as landlords hope to get higher rents because of the arrival of known brands and known companies that are really high credit.”

Marks says he expects to see “some sort of correction in rent expectations” in 2018, which may lure independent businesses to storefronts again as landlords realize the national retailers they are waiting for may never come calling. “It’s one of those enduring myths that greedy owners are holding out,” says CPEX’s King. “That’s not a greedy owner, that’s a stupid owner. Let’s say you and I had an empty store and were asking for $10,000 a month, but had three offers at $8,000 a month. At some point we need to say maybe we’ve shot past reality, and we need to adjust to what the market is saying.”

The Search for Solutions

Policies to help small businesses thrive even as chain stores put down roots and drive rents higher are scant. The City Council, in its December report, was withering in its own assessment: “New York City does not have a coordinated plan or policy to promote neighborhood retail development, retail diversity, or to promote small retailers and restaurants.” The report added that at “all levels of government, federal, state, and city, there is a lack of coordinated policy to address the issue of affordability of commercial space … This is in stark contrast to decades of complex policy-making to address affordable housing.”

Small-business advocacy groups like the Small Business Congress and TakeBackNYC agree, and say the solution is to bring the Small Business Jobs Survival Act out of committee, where it has languished for decades. The act would require ten-year lease minimums with a right to renewal, binding third-party arbitration if parties can’t come to an agreement on lease-renewal terms, and restrictions on passing on property taxes to small-business tenants. Proponents of SBJSA also concede that it is unlikely to move forward, blaming the powerful real-estate lobby. “It’s obvious that nothing will happen with this bill under the Bill de Blasio administration,” Kirsten Theodos, cofounder of TakeBackNYC, told the New York Times last year.

City Council Member Brad Lander, who represents a swath of northern Brooklyn from Cobble Hill to Kensington, says he doesn’t believe a version of the SBJSA could pass without state-enabling legislation, meaning that Albany would have to get on board (and he doesn’t believe that’s likely). In December, Lander and other legislators announced a proposal for the “Mom & Pop Rent Increase Exemption,” a program that would provide a property-tax abatement for owners who offer multi-year leases with set limits on annual increases. The state legislature would have to approve the proposal to authorize the city to create the tax program.

The 86th Street retail corridor in Bay Ridge has become a kind of outlet mall, with such retailers as Banana Republic and Victoria’s Secret

Though Lander is a vocal supporter of small businesses and likes to issue public smackdowns of chains behaving badly, small-business advocates say Lander’s proposal, along with other proposals for small-business tax cuts or rezoning, don’t go nearly far enough. “What good is a tax cut if you don’t have a lease?” Theodos, of TakeBackNYC, wrote in the The Villager in 2017.

Responds Lander: “I deeply associate with the anger and anxiety and loss people feel [when local businesses close], but that doesn’t mean there’s a silver bullet the City Council can use. I hope we will do more. I pushed hard to get the retail diversity report done, and I want to see the city implement more pieces of it.” In the meantime, he urged Brooklyn residents to vote with their dollars. “Sure, when there’s a new Starbucks people grumble, and fair enough. But we have a lot of great independent coffee shops, so go patronize them.”

Olivia LaVecchia, a research associate at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, said other cities have been more aggressive about controlling the retail mix. “We’ve seen New York lagging other cities on this front, so it’s exciting to see any type of proposal,” she says of the proposed legislation. “There are a lot of effective policy measures that are less direct than rent intervention that justify using some of the established powers of cities, like zoning, to create a built environment that is hospitable to and supportive of locally owned businesses.”

San Francisco is frequently held up as a model of retail diversity; formula business restrictions in place since 2004 set limits on the number and type of chain stores allowed in neighborhood business districts, resulting in a more robust mix of national and local retailers. LaVecchia also pointed to a pilot program in East New York that requires real-estate developers to set aside space for neighborhood businesses as another example of things the city is testing to help small-business owners compete.

For the Brooklyn Chamber, the ultimate goal for Brooklyn is that chain retailers and mom and pops all thrive. “We need to incentivize owners of property to work with and keep independent stores in place,” says the Chamber’s Hoan. “There’s a sense that there’s competition [with chains], and there’s certainly an impact on real estate. But the reality is you have seen the growth of Dunkin’ Donuts, Starbucks, and 5 bajillion independent coffee shops and roasters. All these things can coexist. We can have it all here in Brooklyn.”