Is Brooklyn’s Blockchain Industry Becoming a Real Business?

Certain parts of Brooklyn these days feel like a version of what you might imagine the early days of Silicon Valley were like while the internet was being born. Excited developers and entrepreneurs are leaving behind the suits and briefcases and glass towers of Manhattan for startup T-shirts, jeans, book bags, and renovated factories. This time around, the tech set is working around the clock to produce what they think will be the new internet: the blockchain.

Last week many of them gathered in the Williamsburg Hotel for a conference called Brooklyn Tech Week, hosted by the hotel’s Brooklyn-born and based owners, Heritage Equity Partners, and featuring many speakers from Brooklyn’s (and maybe the world’s) largest blockchain company, ConsenSys.

In the last two years, blockchain technology, and the tokens based on it, cryptocurrencies, have been both the hottest and the most overheated subjects in the technology world. East Williamsburg-based ConsenSys, which develops applications for the Ethereum blockchain platform, was founded in 2015 and already has about 1,200 employees around the world.

New York City’s interim chief technical officer, M. Alby Bocanegra, welcomed attendees at the Williamsburg conference last week (Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Tech Week)

“Last year was all about buying Lambos. This year we all have to debate Nouriel Roubini,” said ConsenSys’s chief marketing officer, Amanda Gutterman, referencing Lamborghinis, a symbol of the quick fortunes made in cryptocurrencies and the economist nicknamed “Dr. Doom,” who gained fame by correctly predicting the financial crisis a decade ago and who now has staked out a space for himself as the preeminent blockchain bear.

Will blockchain revolutionize the infrastructure of the global financial system—and even much more? Is it fool’s gold? And outside the hype, what is actually happening with the technology that has found a home base here in Brooklyn? We headed to the conference to try to get some answers on the current state of blockchain technology.

A Regular, Struggling Business

One thought many people sounded at the conference was a recognition that the cryptocurrency party had come and gone. Now it’s a question of how long into the next afternoon the hangover would last. Last fall and winter, cryptocurrencies across the board, but led by bitcoin and ether, experienced a speculation boom with few precedents in human history, enriching those early adopters who owned tokens. This year has brought an unwinding of that speculation, with the prices of nearly all cryptocurrencies retreating between 50% and 75%.

Brittany Laughlin is a partner at Lattice Ventures, a seed-stage fund that invests in many blockchain companies. During her panel discussion, she said that it’s time for blockchain startups to reign in their predictions and start producing.

“There are these very grandiose plans. People say ‘We’re going to be the new internet.’ Okay, how are you going to do that?”

It was a thought seconded by Charlie O’Donnell, a venture capitalist who started the fund Brooklyn Bridge Ventures. He said in his keynote that the companies in the blockchain space needed to start answering the same questions startups in any industry have had to answer for decades: Does someone want to buy what I just built? Does a consumer want to use what I just made?

Earlier this year, the Ethereal Summit, hosted by ConsenSys, drew an estimated 2,000 blockchain aficionados (Photo by Steve Koepp)

“I think there was a time when investors got very excited about the use of blockchain and there was a land grab to jump into the space, but I think that window is closing and they want to see market size and traction and the same questions we’ve always had,” he said.

Yossi Hasson, the managing director of the startup incubator TechStars, likened blockchain to the birth of the internet, but noted that the internet did actually take a long time to reach its promise, and had plenty of false starts.

“In blockchain we’re still sort of in the Linux phase but we’re seeing people trying to build the new Facebook,” he said in a panel. “You still have to build the infrastructure. Right now the infrastructure is slower and harder to use than its competitor, which is cloud-based technology… We are seeing some applications, but there’s very few that actually fit into the box of why it’s important to use blockchain.”

Many people at the Brooklyn event had been at a different conference the week before, DevCon IV, in Prague, Czechia. DevCon is an annual conference for Ethereum developers that has grown in recent years to be one of the toughest tickets in the blockchain world.

Sam Cassatt, the chief strategy officer at ConsenSys, told The Bridge it had a different feel this year.

“In previous times, when people were just focusing on the [cryptocurrency] price and there’s a lot of exuberance, there were a lot of people trying to capitalize on that exuberance and trying to shill their random token project,” he said. “At DevCon last week, there was a lot of focus on core platforms, on ideas, on pushing the next boundary and I think that’s a really healthy thing. It shakes out some of the noise.”

The Blockchain Impact in Brooklyn

Based in a sticker and graffiti-covered brick building in East Williamsburg, ConsenSys was one of the first blockchain companies, founded by the co-creator of the Ethereum blockchain (the second-largest blockchain after Bitcoin), Joseph Lubin. He is thought by some to be the single largest holder of Ether, and in February, Forbes estimated his fortune to be between $1 billion and $5 billion, although the price of ether has dropped by 75% since then. Still, ConsenSys is a hub of economic activity, a new industry on a block of old factories and warehouses that have been converted into co-working spaces and cafes.

“When people come from international consulting firms and I see people walking down the street looking confused in Bushwick, I tell them it’s actually that door there with the stickers and graffiti on it,” Cassatt explained, with a laugh.

The famous sticker-covered front door of the building housing ConsenSys in East Williamsburg (Photo by Steve Koepp)

Aside from the jobs, there are ancillary economies growing up around the blockchain space in Brooklyn as well. Around the corner from ConsenSys’s headquarters is a building called the Bushwick Generator. Currently, the space is being used as a “community oriented innovation hub” and when it’s fully built out will bring 100,000 sq. ft. of office and retail space to East Williamsburg. The space holds a regular blockchain meetup and is the base of an organization called the Bushwick Blockchain Alliance. It’s owned by Heritage Equity Partners, headed by Brooklyn real-estate maven Toby Moskovitz, and received a more than $30 million loan from Jared Kushner’s Kushner Credit Opportunity Fund to bring the renovated industrial building online.

It’s not just real estate, though. We met a media entrepreneur, Rachel Siegel, who lives in Bushwick and recently created a design business around blockchain technology. She was at the conference for networking, she told The Bridge. Her company, Blocknoodle, is an animation company that creates marketing videos for blockchain startups explaining what they do. Siegel said business is good. In fact, she recently expanded her repertoire to include viral video production. Her most recent work, Top Six, features her writhing on the steps of the New York Stock Exchange in underwear bearing the XRP brand (another cryptocurrency) singing a rewritten version of Britney Spears’ Toxic. (Top Six refers to the top six cryptocurrencies.) The video generated a few thousand views on YouTube and dozens of comments on Reddit.

“My thesis is there’s no way to get a common consumer invested in cryptocurrency, wondering what’s going on about blockchain technology,” if the message is too tech-heavy, she told The Bridge. “Not everyone can understand that.”

All of it fits into a trend of tech companies increasingly starting in Brooklyn and foregoing the crossing of the East River, said Charlie O’Donnell, in his keynote.

“Over the last ten years the critical mass of people who start companies is more likely to live in Brooklyn than in any other place. When people start thinking of lifestyle and family and commute people are wondering, ‘Why am I commuting into the city?’ There’s a lot more co-working spaces in Brooklyn. There’s now three or four VC firms located in Brooklyn. If you look at where investors actually live, a Brooklyn company trying to pitch a Manhattan VC, the founder probably has a better shot of getting breakfast in Brooklyn with that investor rather than going into the city and pitch.”

Where’s the Political Revolution?

One of the biggest reasons blockchain and its cryptocurrencies have captured the imagination of so many people is that it is not just a technology. Its use can also be seen as a political act. Blockchain’s supporters cite its inability to be censored and its pre-programmed dilution of the token supply as core features.

With free speech a trending topic once again in our country’s political life and inflation at crisis levels in some countries, these would seem like features that could be great justifications for the technology. But transactions on the blockchain for anything other than cryptocurrency speculation remain exceedingly rare. So why do people have such a political attachment to the technology?

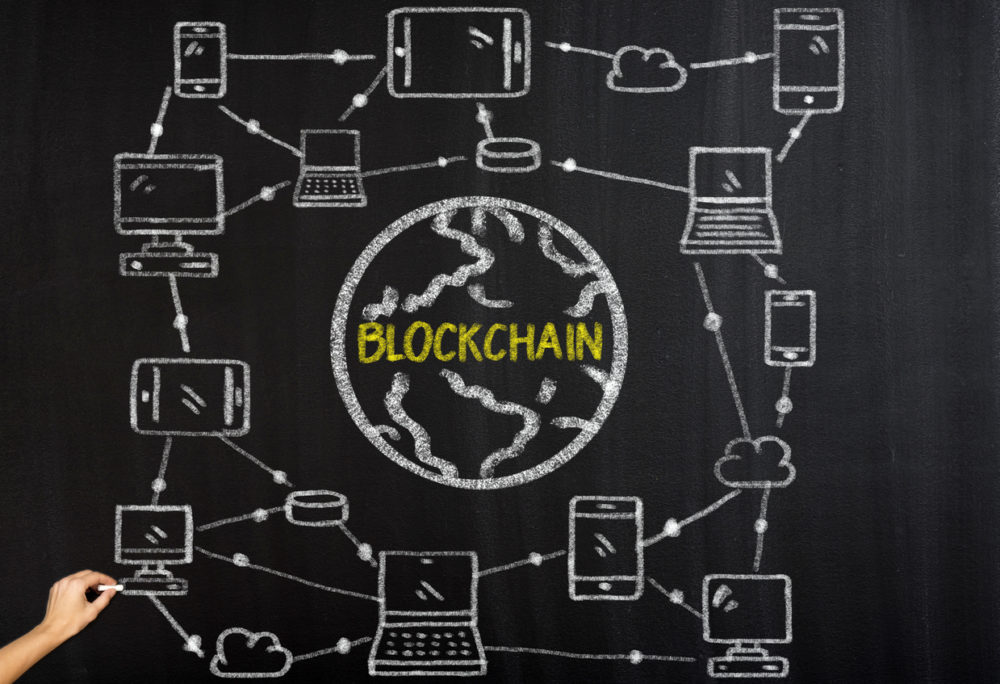

At its base, the original value proposition of Bitcoin was that it could be money transacted digitally with technology that prevented double-spending, meaning that you could not digitally send $5 to Steve and then also send that $5 to Arden. The need to prevent this double spending inspired the creation of blockchain, which is essentially a database of every transaction that occurs on it. This database is maintained by computers, by a lot of computers, and is published freely for inspection, although people’s names have been replaced by long strings of letters and numbers.

Inside the Bushwick Generator, home of the Bushwick Blockchain Alliance (Photo courtesy of the Bushwick Generator)

The result of this invention is that it could solve the core function of the many companies who’ve built massive businesses doing the work of exchanging money between people. These would be companies like PayPal, American Express, Visa, Western Union, banks, pretty much any company who takes money from Steve and sends it to Arden and takes a fee to make sure the accounts are reconciled.

This has political ramifications as well. Under current systems of electronic funds transfer, banks and other financial companies have veto power over which transactions are permitted. Last week, the U.S. government re-imposed sanctions on Iran that disallow many money transfers with the Iranian government and nationals. PayPal removed accounts belonging to organizations it views as politically objectionable, including the far-right-wing Proud Boys and some chapters of radical leftist Antifa.

This financial censorship, or “deplatforming,” isn’t possible using blockchain technology. Since there is no middleman, and hence no organized body that oversees payment processing, there’s no way asset transfers can be shut down on a blockchain; there’s no one to do it.

A second reason people are interested in cryptocurrency is that the generation of new tokens is not a matter of anyone’s discretion. On nearly every blockchain of repute, there is a certain rate at which new tokens are added to the ecosystem, and thus a steady (and low) rate of inflation. There’s no governing body like the Federal Reserve Board controlling the money supply based on economic judgments. It’s this fact that got many people interested, including Sam Cassatt, who was a graduate student in the neuroscience department at Johns Hopkins University when he became intrigued by monetary policy and theory during the 2008 financial crisis.

“It’s the first time ever that actors other than nation states can issue a currency and so it changes that whole dynamic in who gets to be the player that controls that,” he told The Bridge at the conference. “Control of the money supply is one of the most important tools for governments.”

The initial way in which blockchain has subverted traditional financial structures its through use as a means for raising investment money. Through fundraising methods called alternately an Initial Coin Offering (ICO) or a Token Generating Event, a company creates its own tokens, the currency of its app, and sells them to the public.

(Illustration by Mario 31/iStock by Getty Images)

Investors buy the tokens either because they want to be able to use the product, akin to buying tokens at an arcade, or they buy the tokens because they expect the app to go into heavy use, generating high future demand for the tokens, allowing the purchaser to sell them at a markup—or often a bit of both reasons. What ICO investors don’t get is equity in the company or a dividend, the two things investors usually receive when they put their money up for a company.

Blockchain applications have raised staggering sums from ICOs. In 2017, a startup called Filecoin raised $257 million in a coin offering and a new blockchain called Tezos raised $232 million. These sums were raised because anyone, anywhere in the world, could participate in the fundraising to whatever degree they liked. Rather than venture capitalists picking startups to invest their wealthy investors’ money in, anyone with a computer could put their money into an ICO.

“I don’t think there’s ever been a time in history when an entrepreneur has these kinds of options and this distribution of power,” remarked Hasson, the TechStars executive, at the conference. “All of a sudden there is a plethora of capital that can be distributed globally with this kind of technology.”

Some venture capitalists, however, don’t think it’s quite as simple as that. “It has never been the case that VCs were the only source of funding,” said O’Donnell, the Brooklyn venture capitalist. “There are lots of things that have come out and said, ‘Oh this is the end of VCs!’ You still at the end of the day have to convince a person to put their money in your company. You still need to do the blocking and tackling work.”

The investing landscape is changing, however. In 2018 regulators took a good look at fundraising through token offerings, with the Securities and Exchange Commission indicating that it will be enforcing fraudulent transactions much more diligently, a move that has put a significant chill on the practice, in part because of uncertainty about how the enforcement will be applied.

“I think we’re at a bit of a logjam,” said Rodrigo Seira, a lawyer with the blockchain boutique firm DLxLaw, explaining why the prevalence of coin offerings is way down in the U.S. Many blockchain startups are now raising money through more conventional means. “I think it’s actually overcorrected,” Seira explained. According to a study by accounting firm Ernst & Young, released last month, of the 141 largest ICOs in 2017, 86% are trading below their listing price, 30% have lost almost all their value, and an investor purchasing a portfolio of tokens would have lost on average 66% of their investment.

In conversations with nearly everyone at the conference, it’s clear the sentiment is that the days of simply adding “blockchain” to a company’s name and seeing its valuation jump are over. But that could be a good thing for the industry, as expectations are recalibrated and actual, unsexy work gets done. At the Williamsburg Hotel, uncertainty ran high and hype was questioned, but the promise of the technology persisted. The coming years will bear out whether this technology will, in fact, become the new internet or a case study in speculation for the economics textbooks of the future. Or somewhere in between.

A Showcase for ‘Smart Glasses’ Opens in Brooklyn

An augmented-reality eyewear company that has kept its work under wraps for several years will make its retail debut in Brooklyn this week.

Tuesday marks the grand opening of the Focals by North retail storefront at 178 Court St. in Cobble Hill. The company, which will occupy about 7,200 sq. ft. over two floors, says this will be the world’s first smart-glasses store. “It’s been an exciting opportunity to launch something that’s weird, and new, and fun,” said Adam Ketcheson, the company’s chief marketing officer.

North is a Canadian startup founded in 2012. The company—which develops futuristic, human-to-computer interaction products—has raised over $135 million from investors that include the Amazon Alexa Fund, which invests in apps for Amazon’s virtual assistant.

The new shop’s ground level features hovering screens that give customers a preview of the display inside the glasses

These glasses are North’s highest-profile product release, following a gesture-control armband that the company has discontinued in order to give its full attention to the new product. So-called “smart glasses” have struggled to gain traction in the past, from Google Glass to a failed attempt by Intel.

But North is counting on a few things to make smart spectacles actually stick. Focals are custom-built glasses with a transparent, holographic display that only the wearer can see. From this display you can scroll through texts, travel directions and weather notifications. The glasses even allow you to hail an Uber and speak with Alexa.

The display is controlled with a Loop, a small finger ring with a tiny, four-way joystick that’s included in the purchase, along with a case that doubles as a battery charger. The glasses sync with the wearer’s Android or Apple iOS device via Bluetooth.

A model wears the classic version of the glasses, in black. They can be fitted with either prescription or non-prescription lenses

Glasses come in stylish designs, more like Warby Parker (which also has a store in the neighborhood) than geeky Google Glass. The idea, according to the website, is to make the technology “invisible—there when you need it, gone when you don’t.”

Ketcheson told The Bridge that retail space is a necessity, as you have to be custom fitted for Focals. It’s also crucial, he noted, for customers to understand how the technology looks and feels. “It’s incredibly important for people to get a hands-on experience, especially at our price point,” he said. (Focals will be offered in a variety of styles at $999.) “The entire retail model is so people can immersively understand what it is and get the right fit.”

North tapped San Francisco architecture firm Envelope A+D to customize their showroom in Cobble Hill, which is opening simultaneously with one in Toronto. The two-tier space, Ketcheson said, allows for “different phases” of a store experience.

An example of the Focal’s display, which the company says is based on its own proprietary “retinal projection technology”

You walk into “immersion stations” upon entering the storefront, which offer a simulated version of the holographic display. (North designed the display to hover in front of you with a crisp image, but unobtrusively so.) After you see a preview of the display, employees guide you upstairs to “sizing rigs.” This is where you get a 3D scan of your head, offering a precise view of the shape of your head and face. That scan will allow North to custom-build the glasses. “It’s a little bit like stepping into the future,” as Ketcheson put it.

Then employees allow you to try out different sizes, styles and colors. Once you’ve decided on the details, the information is sent to North’s manufacturing facility in Canada. The final product is sent to the store for one last customer fitting. “It’s not unlike a traditional eyewear journey,” Ketcheson said. “The big difference is there’s way more tech along the way.”

North was intentional in choosing Cobble Hill for its first U.S. showroom. “We want our first wave of retail to be in neighborhoods,” Ketcheson said. “We’re looking at big international cities that have an influence on the rest of the world, but within those cities be neighborhood-based.”

The more intimate experience in a Brooklyn neighborhood like Cobble Hill, he said, was preferable to “a high-traffic SoHo location.”

Cobble Hill was also chosen due to its tenant mix and a neighborhood demographic “focused on lifestyle … who they are, how they curate their look,” Ketcheson said. “They’re early adopters when it comes to new things. But it’s not as showy as other parts of the city.”

North has been quietly building its Brooklyn retail team, alongside a company that now employs 450 people. “We have essentially been working on this project in secret for over four years,” said Ketcheson. The Cobble Hill opening marks a notable shift for the company and its public brand.

“For these engineers, physicists and scientists to now see we’ve built a retail store to house and sell a product they’ve slaved over in secret for four years—it’s unbelievable,” he said.

Inside the Serious Business of Opening a Comedy Club

After nearly a decade of running a successful comedy club in the East Village, Marko and Tia Elgart’s business needed a new home. Their lease was expiring and they had been looking for a new spot in the obvious place, Manhattan. Then, one day while they were exploring the area around Barclays Center, the couple considered Brooklyn.

They saw young people and tourists enjoying the new nightlife, and shopping the Apple Store and Whole Foods. “And with the train station, it’s more accessible than almost anywhere in the five boroughs,” Marko told The Bridge in a recent interview. Plus, he and his wife already live in Park Slope, where they’ve called home the past eight years.

Marko and Tia were also well aware at the time that Brooklyn did not have a dedicated comedy club. “Brooklyn has a lot of rooms that do comedy,” Elgart said. “There’s Union Hall, there’s also The Bell House, but those are event spaces,” he said, not the same type of venue as, say, Carolines, the famous comedy club in Times Square.

Proprietors Marko and Tia Elgart in their new venue, not far from where they live in Park Slope (Photo by Caleb Caldwell)

Indeed, for all the culture in Brooklyn—from the mainstream events at Barclays Center to the popping parties at House of Yes to the fine art of the Brooklyn Museum—the borough hadn’t had a comedy club of its own … until now. In July, the Elgarts’ new venue, Eastville Comedy Club, opened its doors to paying customers for the first time at 487 Atlantic Ave., right on the edge of the Brooklyn Cultural District.

On opening night, in front of a 120-seat full house, revered performers like Janeane Garofalo (Wet Hot American Summer), Todd Barry (Flight of the Conchords), and Christian Finnegan (Chappelle’s Show) nailed their punch lines and sent drink-swigging comedy fans into convulsions. The new spot is sleeker than the old one, with a freshly plastered subway-tile stage backdrop, high beamed ceilings, and an exposed-brick bar area just past the all-glass façade.

While the move seems like a natural migration now, the road from Manhattan to Brooklyn had its share of potholes. After founding their original club on East 4th Street in 2008—Marko had started producing shows after a short stint as a stand-up performer—they had built up a loyal following, based on performances by rising stars and recognizable stage veterans like Sarah Silverman.

Comic Akaash Singh performing on opening night. Says his website: “He wanted to be a doctor like his uncle and graduated pre-med from Austin College. Naturally, the next step was to move to Los Angeles and become a comedian.” Next stop: New York City (Photo by Adina Lerner, courtesy of Eastville Comedy Club)

But it was time to go. The Elgarts had landlord troubles and felt the need for an upgrade. “The old space was kind of a shithole dive, which was cool ten years ago, but not really anymore,” Marko said. “Our lease was expiring. I started negotiations with my old landlord,” who he describes in colorfully unflattering terms. “He just wanted a lot of money, additional taxes. It was way more than we were willing to pay.”

Finding a new place for a comedy club, however, is a lot harder than finding one for, say, a toy store. The Elgarts scoped out a new location on Avenue A, situated within the boundaries of Community Board 3, the same district as their old club. They crossed their fingers and hoped for the best. Elgart said CB3 had made business at Eastville difficult for him over the years, forbidding the front of the club to operate as a full-time bar, which meant the staff could sell drinks only to show-goers.

When the Elgarts proposed their move to the board, Marko said they approved it, but with impossibly burdensome stipulations. “They were like, ‘You can only be open til 12 a.m. on weekends, you can’t have any lines outside,’ just completely shitting all over the business we had for 10 years.”

In an email to The Bridge, Susan Stetzer, District Manager of CB3, wrote that the Elgarts wished to move the club “to a very saturated area,” when it comes to the number of establishments owning late-night liquor licenses. She also wrote that that part of the neighborhood was home to “a great deal of noise complaints reported to the community board,” sparked by commotion on the sidewalk. “No wait lines is a consistent stipulation for businesses in the area and the Comedy Club was not being singled out.”

The comedy club has a bar in the front of the house, separate from the main room (Photo by Adina Lerner, courtesy of Eastville Comedy Club)

Once the Elgarts gave up on Manhattan, they found a place in Brooklyn with a lease that Marko said is much more agreeable than the one he was nearly forced into. After six weeks of renovation at the new space, the club reopened, retaining its original name because, Elgart said, most people don’t make the connection between the moniker and the original East Village location. Nor did he want to throw away a decade of branding efforts.

Summer was a slow season to launch a new club, but Elgart expects Eastville to recoup the cost of the move within a couple years. Tickets for the shows are priced modestly, with a $20 cover charge for weekend shows, a buck cheaper than Eastville was charging in Manhattan. Weeknight shows are $12 per ticket, or roughly 20% less than the prices for many such shows across the river.

The club’s cash cow, of course, is booze. “Ticket prices are a low-revenue source; I would guess 10% or 20%, tops,” Elgart said. There’s a two-drink minimum during shows but Elgart says customers will buy more than that if the waiters work quickly enough. “We staff a little more, and people will drink more than two, you’ve just got to get to them.” Drink prices are a bit higher in the main room than you’d find in your corner watering hole, or even the bar in the front of the club before performances begin.

The Atlantic Avenue club is near other cultural venues, including Brooklyn Academy of Music and Barclays Center (Photo by Adina Lerner, courtesy of Eastville Comedy Club)

Elgart said he compensates the comics competitively, if not a little better than some other clubs, depending on the show’s date, time, and roster. In general, the pay for stand-up performers ranges from notoriously little, sometimes $20 to $50 for comics just starting out, to hundreds or thousands of dollars for headliners.

In Elgart’s case, he said he pays a total of “thousands of dollars a week” to the comedians. “I like being a good boss to everybody. I want to make everybody as happy as I can, but I also have to make smart business decisions because these comics aren’t paying the huge rent that I’m paying, they’re not paying the huge insurance I’m paying.”

The talent has certainly found its way to the new Eastville stage, including Anthony DeVito, a writer on The Break with Michelle Wolf; Mark Normand, who’s starred in two Comedy Central specials; and born-and-bred Brooklynite Wil Sylvince, who’s toured the country with the likes of Damon Wayans and Katt Williams.

“When I first entered the new Brooklyn location of Eastville Comedy Club I was surprised to see how fresh, clean, and magnificent it looked,” Sylvince wrote in an email to The Bridge. “The actual room where the comedy show was happening was excellent. As I walked out after my set I thought—this is just what Brooklyn needed.”

Spats with community boards, landlords, and perhaps the occasional comedian aside, Marko Elgart says he and his wife—who have two young children—enjoy running Eastville. “I love it,” he said. “I’m very fortunate that I’m not stuck in a cubicle from 9 to 5; that’s not something I want to do; I’m my own boss. It’s a lot of hard work, but we’re lucky to be in the business.”

Joel Hamilton, co-owner, Studio G Brooklyn

You’ve probably heard music that was recorded at Studio G Brooklyn, the legendary sound laboratory tucked into the border of Greenpoint and Williamsburg. Clients of the space have included Aaron Neville, Bonobo, Ani DiFranco, Tom Waits, Talib Kweli, Sesame Street, Spotify, and many more. Our podcast guest Joel Hamilton, an acclaimed producer and engineer who owns and operates the place along with Tony Maimone and Chris Cubeta, told us how the sophisticated studio was built from scratch over the last two decades.

Studio G was hip from the start, before Williamsburg or Greenpoint were what they are today. The founders had the good fortune, Hamilton acknowledges, of getting started in the right place at the right time. “For me to comment on the studio business is for me to comment on a very personalized trajectory that operated within a very, sort of, DIY scene,” he said, “and then expanded when the DIY scene ultimately bubbles up from the underground and becomes ‘cool.’”

It wasn’t blooming from the beginning, though. Hamilton recalled the Brooklyn nobody knew, as it went from the destination to which “you had to argue with the taxi driver to go over the Williamsburg Bridge” to the place “where everyone wanted to be.” The early days were largely about finding artists willing to make the trek. “That’s a part of the story: convincing people to come to Brooklyn. It’s not like it was the middle of nowhere, it was actually scary to some people. It was worse than nowhere.”

Their location, along with being the new kids in the business, meant that a large source of early clientele were Hamilton’s own friends. “When you’re in a band, it’s usually your friends’ bands are the bands that are coming in to record with you, so that’s a double-edged sword,” Hamilton said. “You have access to more people who need recordings and less people who are going to pay you. You just keep the overhead low.”

Slowly but surely, Studio G built a stronger resume and Brooklyn started to shift. “There was this groundswell of relevant artists that were living in the cheaper neighborhoods out here because the East Village got expensive. Our business model kept evolving to support that new breed of kid that was starting bands in Williamsburg. We just happened to speak the same language. We came from the same set of influences and had enough gear that we could get the job done for them.”

The studio’s infrastructure grew almost as a direct reflection of the community surrounding it. “I had really broken stuff and that was serving a community that could only afford the kind of broken stuff, and therefore they were more patient with me having to kind of make it work,” Hamilton recalled. “And then we moved to the next level because that process and those bands’ patience got me to the next level,” he said.

Soon, artists with higher budgets started coming in. “They were a little less patient with my broken shit but they had a little more money to spend. And so I would take a percentage of that budget and put it into the next vocal microphone or mic pre[amp] or piece of equipment that sort of pushed me to the next level on the infrastructure side.”

Even as the business has scaled up, the ethic has been the same: make the most of the resources you have. “For me the game has always been: If you have $500 available to make a record, make it sound like $1,000. If f you have $1,000 make it sound like $5,000. And that applies even now. If you’re doing a record with a $100,000 budget, you have to make it sound like it had a million-dollar budget.”

The philosophy seems to have worked. Hamilton has been nominated for seven Grammy awards.—By Kora Feder

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Two Brooklyn Democrats Help Clinch New Majorities

Democratic victory was especially sweet in southern Brooklyn last night, where two underdogs defeated GOP incumbents and became part of new majorities in Albany and Washington.

It was just past midnight when the 33-year-old State Senate candidate Andrew Gounardes emerged as the winner in his bid to upset Marty Golden, an eight-term Republican icon. “We could see this huge crowd of people that had spilled out onto the street to greet us,” said Dara Adams, chief strategist for the Gounardes campaign, who made his way with colleagues from their headquarters in Bay Ridge to the victory party a few blocks away at Cebu Bar & Bistro.

“It was pretty insane, it was pretty incredible. There were so many people that voted for the first time, people who’d never been involved in politics before, and there were people who have been waiting 16 years to have a representative that they feel shares their values.”

The celebration was similarly jubilant among supporters of Max Rose, who won a close contest with Republican Dan Donovan for the 11th Congressional District, which includes Staten Island and a swath of southern Brooklyn. “Four hundred and sixty two days ago, we launched this campaign to do things differently,” the Brooklyn native told supporters at the Vanderbilt in Staten Island. “We were in this to change politics irrevocably.”

While the hoped-for blue wave had its limitations on the national level, in southern Brooklyn it washed away two remnants of GOP control. Gounardes ousted the only current Republican state senator in the borough, while Rose defeated the only Republican Congressman. Rose’s winning campaign, which drew attention and money from the national party, helped solidify a Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. In New York State, the victory of Gounardes and other Democratic candidates powered the party’s takeover of the Senate, putting control over state government (including the Assembly and governor’s office) in Democratic hands for the first time in a decade.

For Bay Ridge native Gounardes, a community activist and general counsel to Borough President Eric Adams, it was a second try at defeating Golden, an affable but old-school politician. Gounardes won with 31,168 votes, or 50.9% of the total, as of today’s count. Update: Golden has refused to concede, pending a recount next week.

State Senate candidate Gounardes during the campaign, with U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, at center (Photo by Trey Pentecost)

The Gounardes-Golden battle became a heated one in an otherwise quiet district, producing a series of contentious debates, including one in which Gounardes declared that Golden has “a superficial relationship with the truth” and criticized Golden’s vote for a bill that would have allowed insurance companies to cease coverage of pre-existing conditions. “No one should be selling cupcakes to pay for cancer treatments,” Gounardes said. Another flash point was the role of a Golden staffer in the Metropolitan Republican Club, which hosted the Proud Boys white nationalist group on Oct. 12, shortly before a street fight with protesters.

The Rose-Donovan race had its own twist, which was the challenge to the Democrat of running in the city’s most conservative Congressional district. (Rose’s winning tally was 95,458 votes, or 52.8% of the total.) Rose, a decorated Army veteran who served in Afghanistan, avoided liberal orthodoxy and sometimes tacked to the right of his opponent. He took issue with Democratic leaders from Mayor de Blasio to House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, while questioning the need to impeach President Trump. Yet his policy positions were often in line with his party on health care, taxes and immigration.

“The story of this country has always been that no matter our differences, no matter the challenges in our way—we do what others say is impossible,” Rose said in a victory statement. “It has never been about what party you are. On Staten Island and in South Brooklyn, we put country first. We believed in an America where the government has got our backs. An America where it doesn’t matter your color, gender, sexual orientation, rich or poor—the American dream is a dream we can all share. We believed. And we won.”

In January, Rose will join a House majority that will give the Trump resistance legislative clout, complete with subpoena power. Among the first efforts will be ethics reform in such areas as campaign finance and voting rights. “At the same time, the incoming chairs of 21 House committees will be looking for ways to hold the Trump Administration officials’ feet to the fire, mainly by pressing forward on investigations they feel were ignored under the Republican majority,” reported Time in the election’s aftermath.

In Albany, the consolidation of power has rekindled a legislative wish list, including legalization of recreational marijuana, campaign-finance reform, gun control, climate-change measures, and the rebuilding of mass transit. “You have a raft of legislation that has been bottled up for decades,” State Senator Brad Hoylman, a Manhattan Democrat, told the New York Times. “We’re going to be testing the limits of progressive possibilities. I hope we look a lot more like California.”

“We’re so happy with the outcome of these elections,” Mallory McMahon, co-founder of the community organization Fight Back Bay Ridge, told The Bridge this morning. She characterizes her group, which was founded as a reaction to Donald Trump’s election, as a check on local politicians as well. “We know that our work is not done,” McMahon said. Her group knows “full well that these representatives, just because they’re Democrats, doesn’t mean they’re always necessarily going to do what we want, and we’re totally prepared to hold both Rose’s and Gounardes’s feet to the fire as well.”

Merchants Embrace Art to Give Smith Street a Boost

Smith Street needs a lift. The once-thriving restaurant row of more than a decade ago has suffered from a double whammy of economic factors in recent years—rising rents and listless foot traffic—that have left it with empty storefronts and a sometimes lackluster vibe.

But last week a jolt of energy arrived in the form of a vibrant mural spanning three empty storefronts on the block between Douglass and Degraw streets. Bursting with dreamlike scenes celebrating the borough’s history and diversity, “In Unity There Is Strength” is the work of Argentinian street artist Magda Love, who was commissioned by a nearby art center, The Invisible Dog, and a neighborhood group seeking to establish a Business Improvement District (BID) for the area.

City Council Member Brad Lander does the honors at the ribbon cutting. Said he: “People are going to enjoy it as they walk by. It animates our neighborhood, as public art does” (Photo by Steve Koepp)

“We recognize that we have an issue with these vacancies because we get these little strips of blight. So we looked for an imaginative way to break the cycle,” said Heidi Cunnick, co-chair of the steering committee for the Court-Smith BID Formation Effort, as the mural was celebrated with a ribbon-cutting. The group hopes that the creation of the mural is a persuasive demonstration of the kinds of projects a BID could undertake to brighten and promote the retail corridor, drawing in more visitors from the neighborhood and beyond.

“We can’t just depend on the community here. We need to make it a destination,” said Dawn Casale, a co-chair of the BID committee and co-owner of One Girl Cookies, which opened its Dean Street shop in 2006 and has since expanded to Dumbo and Industry City. Unlike some other Brooklyn neighborhoods, which lure visitors to a waterfront or park, she said, Smith Street lacks a particular drawing card. “We need to create something else, and our vision of that is art,” Casale said, given the still-high population of artists in the neighborhood.

In the last several years, Smith Street merchants have blamed declining pedestrian traffic for slowing revenues. Casale agrees, attributing the trend to several demographic factors beyond just the impact of e-commerce. “The makeup of the neighborhood has changed dramatically,” she said. One trend is the conversion of multi-family town houses into single-family homes, decreasing the population density, she said. Another is the increasing number of two-income families, she said, in which the parents tend to want to spend more time on activities with their kids and less time shopping.

Muralist Love strives to raise consciousness about social and environmental issues (Photo by Kathi Littwin)

The BID effort began in 2014 as a small group of volunteers, Cunnick said. Around that time, a wave of pioneering Smith Street stores and restaurants were shutting down, inspiring headlines like “The Rise and Fall of Smith Street.” Even as the overall neighborhood has become more prosperous, the proliferation of empty storefronts and the arrival of more national chain stores have put a damper on Smith Street’s DIY spirit. Court Street, meanwhile, where commercial rents are higher, has attracted a superabundance of real-estate offices.

The mission of the BID would be to promote a healthy mix of businesses by making the streets cleaner, greener, and more vibrant. A BID is a public-private partnership in which property owners within the district pay an assessment on their tax bill each year. The proposed Court-Smith BID, which would include those two streets between Pacific Street and Second Place, has an estimated annual budget of $700,000. In an example cited by the BID group, a Class A commercial property with a 20-ft. storefront would pay an annual assessment of about $1,090.

The money raised would be spent on sanitation, maintenance, beautification, community marketing and other benefits for the merchants and property owners. As the neighborhood blog Pardon Me for Asking has pointed out, the sidewalks of Court and Smith streets would benefit from more attention to trash collection.

Love (on ladder) putting the finishing touches on her mural (Photo by Kathi Littwin)

City Council Member Brad Lander, whose district includes a large portion of the proposed BID, performed the ceremonial ribbon-cutting and called for more help for small retail businesses.

“Running a small business in New York—boy, it’s got to be a labor of love to navigate all these challenges,” he told the small crowd. “We’re not doing enough as a city to show up for our small business people. That’s a loss for us as much as for them. Small commercial strips are what give our city its character.”

Zach Owens, manager of the BID program for the Small Business Services department, said the city now has 75 BIDs up and running. They represent 93,000 businesses and annual investment of $148 million. While the city provides support services for the BIDs, as does the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, their creation depends on enough local property owners and commercial tenants signing up to pay for them. “It has to be a community-led effort. It’s a bottom-up approach,” said Owens.

“People think we [already] have a BID but are not doing a very good job,” observed Cunnick. She and her colleagues hope their ebullient mural helps rally support for their proposal so they can get their long-proposed BID up and running.

Tokens of Support for Beto O’Rourke, Made in Brooklyn

Marilyn Descours, a 65-year-old retired baker and restaurateur in La Grange, Texas, is an avid supporter of Beto O’Rourke, the Senate candidate who’s aiming to upset Ted Cruz. Her husband thought she was crazy when she showcased her support for the Democrat on the bumper of their car, for all in their red-leaning town to see. So when she saw on Instagram a photo of a small, irregular-shaped round object, something like a coin painted red, white, and blue, with the raised, hand-lettered slogan “Beto/Better,” she was intrigued. Eventually, she tracked down the item’s creator, a Brooklyn street artist named Beriah Wall.

Wall, 71, who lives and works in Red Hook, has been living and making guerrilla art since the 1980s. The “Beto/Better” coin Descours saw is part of a unique, sprawling, decades-long project, wherein he disperses his tokens in obscure nooks and crannies of the city landscape. He might tuck them into the stonework of building facades, throw them into school yards, or leave them balancing on the door of a parked car if the driver has a bumper sticker he likes.

But Wall’s work manages to spread outside New York. He gives boxes of the tokens to friends traveling abroad, or admirers like Descours who contact him online. When Descours received a box of O’Rourke tokens, she immediately began distributing the coins in La Grange, leaving them on ledges, on the driveways with O’Rourke signs nearby, and impromptu spots like a bench outside of a grocery store.

The artist in October in his Red Hook studio, where he also makes abstract paintings (Photo by Robert Nickelsberg)

“I put one on my dog’s stomach and took a picture for Instagram,” she says. She also, with Wall’s permission, sold tokens to O’Rourke’s supporters as part of a small, grass-roots fund-raising effort (the $150 raised was duly mailed off to campaign headquarters). Other collaborators are handing out Wall’s O’Rourke-inspired work in Austin, Houston, El Paso, and San Antonio.

Wall has never done an issue-specific campaign outside of New York City before, but his initial support of O’Rourke was inspired by the candidate’s driving tour across Texas. “The idea of a Don Quixote taking on Ted Cruz seemed like a great political story, something I’d like to be a part of,” he says.

The coins are free and clearly modest in scale—the viewer might easily pass one on the street without noticing it, or mistake it for garbage, a squashed bottle-cap, or a piece of gum. This, Wall says, is a deliberate strategy. “When I was young and ambitious, the guys who were making the coolest stuff were doing vast land-art-type things,” he explains, mentioning Stanley Marsh in Amarillo, Texas, as an inspiration. “My temperament wasn’t suited to negotiating large projects, so it became my goal to see how far in the opposite direction I could go. How small and insignificant could I be and still have an effect?”

A sampling of the artist’s other coinages (Photo by Robert Nickelsberg)

He casts the coins in porcelain clay in issues of 400 to 500 at a time, then hand-paints them with oil paints or custom mixtures of pigment suspended in polyurethane. The messages are usually couplets of one or two words per side, and are sometimes overtly political or topical (“Boil/Oil” or “Diesel/Poison”) but more often espouse an ethos for living that’s casual and simple but meaningful nonetheless.

“Real/Good” or “Be/Little” or “Truth/Beauty” are, Wall says, “ur-issues” that he presses onto his work, and he has returned to them again and again over the years. There are acknowledgements of human imperfection (“I wish I knew/the answer”), denouncements (“Rich/Greed,” “Bigger/Beggar,” “Urn/Earn”), and many statements that are just little moments of communication that don’t take themselves too seriously, like “Squish/Squish” or an “Oink” with a drawing on the other side.

The effect is to have a small, anonymous connection or conversation that causes the recipient to pause, have an insight, or just to smile. Wall estimates that he’s made close to 1 million coins and has spread them as far as Tibet and the Kremlin in Moscow. He likes to think of his work “on many windowsills and in many pen jars, on the corners of many desks, behind the books on seldom used bookshelves, on many corners waiting to be discovered.” The work is free because “it seemed important to eliminate commerce from the artistic experience. By not worrying about selling them, they can touch more people.”

Gallerist Sallie Mize, the programs manager at the Kentler Gallery in Red Hook, the neighborhood where Wall lives and works, commented that Wall’s work is “really special” but “totally outside the mainstream of art in New York City”—something like the early days of O’Rourke’s campaign, when he was driving across Texas as a relative unknown. Wall is not represented by the Kentler, but he donates work to its benefits and often leaves coins on the gallery doors for Mize to find in the morning.

The “defining element,” she says, is that it’s currency, but it’s free. “It’s almost subversive because it’s so understated and anti-commerical,” she says. For people in the know, finding the coins is a delight. Mize once found one endorsing 38th District Council Member Carlos Menchaca in a Brooklyn cemetery, comparatively far from Wall’s Red Hook neighborhood, but still within that council member’s district. “I was totally shocked,” she says. “I was ecstatic.”

Wall’s O’Rourke series of coins follows others he’s done over the years for various local and national politicians. He has come out against former mayor Rudy Giuliani and made coins in support of Barack Obama for President. A coin endorsing Bernie Sanders found its way to the candidate’s hand. And after Donald Trump’s election, a good portion of 2017 was devoted to anti-Trump messaging such as “Donald/Doom,” “He’s dirty/ He lies,” and “Trumpty/Dumpty.”

Cristy Herman, an O’Rourke volunteer now distributing Wall’s work in San Antonio, agrees. She too was inspired to campaign by negative feelings about Trump. Herman is an “ambassador”—“the smiley face between the campaign and people”—and has been working full time going to rallies and events, talking to people about her candidate.

Marilyn Descours, an O’Rourke supporter, took this photo of her dog with the coins for her Instagram page

She uses a series of Wall’s coins with a “Beto/Better” slogan on one side and a Texas flag on the other as a conversation-starter with younger voters. “[Wall] wanted me to just put them places around town and be mysterious” she confides, but she discovered that handing one to someone created a moment of open-mindedness that fostered connection. “When we first started it was so hard to get young people to talk to me,” she says. “They thought Ted Cruz was someone from Iowa who had run for president. They didn’t know he was our senator.”

Herman believes the Texas flag on Wall’s coins helped young people realize the issue was for them. And the act of receiving the coin and wondering about it was ice-breaking. “People would look at it and look at it and smile,” Herman says. “They would say ‘This is really cool. What is this? I can really keep it?’”

Herman notes that Wall is not the only artist who has been inspired by O’Rourke’s campaign. “The campaign has become very much about the merchandise,” she says. Its black-and-white color scheme is easy to imitate, so people have taken the premise and begun designing shirts and stickers of their own. “I’ve probably seen 70 T-shirt designs,” she says. “I wouldn’t say Beto seems creative, but he is. Maybe that creative streak in him is coming out in everybody else.”

Still, the coins are unique—literally, the surface imperfections and tiny variances in their painting are a considerable part of their beauty, when examined up close. “It’s not just another sticker, you know?” Herman says. And their humble humanist message dovetails with the positivity, energy, and one-on-one connection generated by the campaign.

O’Rourke and his staff, admirers say, have become known for responding to email and otherwise making the myriad small interactions that have led to the groundswell of support for the candidate. It’s a simple but cumulatively powerful approach very much like Wall’s coin project, which also offers street-level connection to anyone who is interested. If Texas will decide Beto is Better on Tuesday remains to be seen.

Editor’s note: this story was originally published by Texas Monthly in a slightly different form.

A Democratic House Candidate Plays Against Type

“I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the First District of Arizona, but I was doing other things. As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi.” —Navy veteran John McCain, after being called out for carpetbagging during his first race for Congress in 1982

“I would’ve come here sooner; I was too busy defending my country in Afghanistan.”—Congressional candidate Max Rose, responding to an accusation that he “is not one of us”

The 11th Congressional District is an exception to the almost uniformly blue carpet of the New York City electoral map. It’s the most conservative Congressional district in the city, the only one with a Republican representative, and went for Donald Trump by eight percentage points in 2016. Staten Island comprises most of the district, but about a quarter of its voters live in a stretch of southern Brooklyn neighborhoods from Bay Ridge to Gravesend.

This year’s Democratic candidate, a purple-hearted, bronze-starred, Afghan War veteran named Max Rose, happens to have been born in Brooklyn, but watching his campaign, and his performance in a recent debate, one must concede that Rose does a pretty good job of appearing to be Staten Island to the core.

Incumbent Congressman Donovan giving his acceptance speech on election night in 2015 (AP Photo/Julie Jacobson, File)

His crossover style is getting results. While the district might have looked like a lost cause judging by 2016 results, in which incumbent Dan Donovan won by 25 percentage points, it’s “now seen as a battleground, attracting national attention, and national money,” noted the New York Times, whose polling on Oct. 23-27 showed Donovan having a slight edge, 44% to 40%, with 15% undecided.

Indeed, to veteran election watchers, this year’s race has provided a dramatic role reversal. Though Staten Island once served as home base to the Jesuitical intellectual GOP State Senator John Marchi, recent Staten Island politicians have not been in the mode of wonky altar boys. They’ve tended to be pugnacious street fighters like Borough President Jimmy Oddo and former Congressman Michael Grimm, who famously once threatened to throw a Brooklyn-born reporter off a balcony.

But despite his occasional descent into verbal malaprops like “denucularizin,” it is the Staten Island native Donovan who is sounding like a wonk from the era of Marchi, calmly reminding voters of two-decades old battles he once fought as chief of staff to the Staten Island borough president. And it is the Brooklyn-born Democrat whose demeanor reminds one of Grimm, without the explicit threats of violence. Still, every once in a while, it looks like Rose is ready to heave Donovan over a balcony.

In some parts of the country, Democrats have nominated candidates who think base mobilization will wake up potential left-wing votes, even in places with no discernible history of having them. But in the 11th, Max Rose is just as happy to throw a right hook as one to the left.

Don’t like Mayor de Blasio (and this district decidedly doesn’t)? Max Rose says he’s doing a lousy job. Don’t like Nancy Pelosi? Max Rose wants to dump her. Against abolishing ICE? So is Rose. He opposes a carbon tax and rejects calls for Trump’s impeachment. In fact, Rose states that, when it comes to Trump, he will not be “a pure, unadulterated obstructionist.”

While some of his primary opponents attacked Donovan’s record as DA from the left, sometimes criticizing his failure to indict cops involved in the death of Eric Garner, Rose is attacking Donovan’s record from the right, saying Donovan was soft on the opioid scourge and linking it to Donovan’s campaign contributions from Big Pharma.

Rose, on the campaign trail, has taken positions contrary to Democratic orthodoxy (Photo courtesy of the Max Rose campaign)

This is not to say that Rose is in any way a conservative. Rose supports health care for all, attacking Donovan for flip-flopping on repeal of the Affordable Care Act. Rose wants to increase taxes on the super rich, opposes Trump’s detention of immigrant children, and attacks Donovan’s wavering position on immigration policy.

What Rose is doing is finding the sweet spot for a constituency which is not all that liberal, but embraces liberal policies it sees in its interest. More importantly, he does this while dog-whistling all the while that he is really “one of us.”

Earlier this year, a lot of national Democrats quietly gave up on this seat once Donovan managed to beat back a Grimm comeback attempt in the primary. Grimm had resigned his seat in 2014 after pleading guilty to felony tax fraud, making him an attractive Democratic target, but Donovan prevailed, largely by making a sharp right turn. Now, veering back to the center, it appears that Donovan may lose to a Democrat who channels much of the Grimm demeanor.

Incidentally, perhaps because Rose knows that he can count on a safe majority of votes from Brooklyn, the borough got considerably less than its share of the recent debate’s attention. Rose did eventually manage to squeeze in mention of the R train, while Donovan admitted he does not even own a MetroCard.

A Rose victory would be seen, especially in the context of Democrats taking the House, as a defeat delivered to Trump in a district he carried. And to some extent, it would be. Democratic Party activists here are loaded for bear and the leadership in both counties is working hard for their Congressional candidate, something they have not always done.

But anti-Trump sentiment here is probably not enough for a Democratic victory. What a Democratic victory here would take is a candidate who can read the local zeitgeist and translate the non-ideological portion of the voter anger which led to Trump’s 2016 victory here—Obama won the district in 2012—into anger against an incumbent regardless of his party.

And, if ever such a candidate existed, it is Max Rose. National Dems and their allies have been spending and contributing large for Rose, regardless of his ideological heresies. While FiveThirtyEight is still calling this race “Likely Republican,” current polling shows the gap dramatically narrower than two years ago. Could an upset be in the cards? Well, it was once inconceivable that voters here would figuratively toss Donovan off the famous bridge nicknamed “the gangplank.” And it is no longer inconceivable.

Can This Young Politician Topple a Brooklyn GOP Icon?

As he sat in a windowless office at his headquarters on 86th St. in Bay Ridge, with a sprawling map of southern Brooklyn on the wall behind him, Andrew Gounardes, the 33-year-old Democrat running for the District 22 seat in the State Senate, reflected on what has been an explosive campaign in a long-quiet district. The last few weeks of debates have sparked talk of truth and lies, cupcakes and cancer treatments, even Nazis and Martians.

With the balance of power in the State Senate on the line, Gounardes’s opponent, Marty Golden, a former police officer and Brooklyn’s only Republican state senator, is seeking his ninth term. But Democrats think they have a real chance this time of upsetting his reign. The district in play covers a wide swath of the borough, including nine neighborhoods from Bay Ridge to Gerritsen Beach.

“Marty Golden is someone who has given a lot to this community. He served in uniform, you can never take that away from someone,” Gounardes told The Bridge. “He’s been elected multiple times by this constituency, so you have to give him that.”

That was about where the pleasantries ended, as Gounardes quickly pivoted.

In a debate in Dyker Heights, incumbent Golden, far right, engaged in a fiery debate with his challenger (Photo by Trey Pentecost)

“This is also someone who wanted to host a women’s etiquette seminar, to teach women proper etiquette and deportment,” he said, “someone who led the opposition to letting people love who they want to love; someone who, in the face of children being torn from their parents’ arms and put in cages, stayed silent.”

If Gounardes, a community activist and general counsel to the Brooklyn borough president, pulls off an upset and flips the seat next week, it could bring the end of what the Wall Street Journal called the GOP’s “last bastion of power in New York.” Partly because of how Senate districts are apportioned, the chamber has long been Republican-dominated. But at the moment, the GOP has only a one-seat advantage. With the governorship and Assembly already in Democratic hands, the turning of the Senate would be a momentous realignment of power.

The larger stakes of the District 22 race have raised the temperature, to be sure, but there’s more to it. This is a rematch, with Gounardes seeking to avenge his loss to Golden in 2012, and a battle of opposites in many ways, with the two candidates differing strongly on almost every issue.

In a series of contentious debates closely covered by local journalists, the vitriol has come to the surface. At an Oct. 23 debate at Xaverian High School in Bay Ridge, Gounardes declared that Golden has “a superficial relationship with the truth,” and later castigated Golden’s vote for a bill that would have allowed insurance companies to cease coverage of pre-existing conditions. “No one should be selling cupcakes to pay for cancer treatments,” Gounardes said.

For his part, Golden—who’s 68 and refined, with neatly parted white hair—reverted to calling Gounardes a “Martian” after Gounardes expressed support for the city’s new policy of allowing transgender New Yorkers to change their gender to “X” on official documents.

Another flash point resonating beyond the borough is the role of Golden staffer Ian Reilly as executive committee chairman of the Metropolitan Republican Club, which hosted the Proud Boys white nationalist group on Oct. 12, shortly before their infamous street fight with protesters. When asked by an audience member as he walked out of the Xaverian auditorium if he would “fire the Nazi,” sources told The Bridge that Golden responded with “I’m not firing him” and “He’s not a Nazi.” Another source said that Golden added: “I’ll give him a raise.”

“I don’t think that Marty Golden’s values represent the values that I was raised with, or the values of southern Brooklyn,” Gounardes told The Bridge at his headquarters, located a little more than a mile from his childhood home.

Growing up in Brooklyn

Along with his brother and sister, Gounardes was raised in a two-bedroom, second-floor apartment in a duplex on 70th Street between Colonial Road and Ridge Boulevard. His grandmother occupied the first-floor flat; he played with other neighborhood kids in the narrow driveway and postage-stamp backyard. Gounardes’s mother was a public-school music teacher during his childhood, and his father a dentist.

From Greek-American descent, Gounardes attended elementary school at a nearby Greek Orthodox school associated with the Holy Cross Church on 84th Street, before moving on to Fort Hamilton High School. “I grew up with a strong sense of community,” which he cites as his motivation for getting into politics. “Service was always a thing we just did, and it was just second nature.”

After a debate with Golden, the challenger has a sidewalk conversation with his prospective constituents (Photo by Trey Pentecost)

“He was always the kid that was out there seeing what he could do” to help others, said his mother, Dianne. “He’s always been driven and really, really focused.” She said he played baseball and the piano, was an avid reader with great interest in history and Greek traditions, and achieved Eagle Scout status. (His earnest ambition is leavened with a dry wit, his inner circle is quick to note.)

As a teen, Gounardes considered entering the priesthood, but about the time he finished up high school, a fateful trip to Washington, D.C., altered his path. Organized by the Manatos & Manatos lobbying firm, the excursion brought him to the capital with a group of Greek-American youths. There they met Greek-American public figures including George Stephanopoulos, George Tenet, and Paul Sarbanes. Gounardes said Sarbanes, at the time a U.S. Senator from Maryland, sat with the teens for two hours and spoke passionately about his family, his work, and what called him to government. “That sealed the deal for me,” Gounardes said.

Gounardes completed a bachelor’s degree in political science at Hunter College in three years, and then worked on Bob Menendez’s successful 2006 campaign for a U.S. Senate seat from New Jersey. Gounardes later moved to Washington, D.C., after taking a job in Menendez’s office as a staff assistant.

“I started answering phones, and I basically worked my way up,” Gounardes said. “People were calling all the time and they were either very friendly or very not friendly on the phones. It was a great way to keep perspective as to what people thought on the ground.”

He left the post to earn his law degree at George Washington University, but returned to Menendez’s office, where he wrote legislation and helped conduct an investigation into Scotland’s release of the Libyan national convicted in the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing of 1988. (The culprit had been let out of prison on grounds of “compassion,” which the Menendez-fronted report said was not justified.)

Shortly after the report was published, Gounardes returned home. “I love D.C., but D.C. is a one-show town,” Gounardes said. “When you’re from New York City, you meet everyone from everywhere, and if you want Afghani food at three in the morning, or three in the afternoon, you can find it.” He added: “Plus, the pizza and bagels in D.C. suck.”

For a year and a half, Gounardes served as director of external affairs at the Citizens Committee for New York City, a nonprofit dedicated to upgrading the quality of life in low-income neighborhoods. Then came his first clash with Marty Golden.

A Rookie’s Strong Showing

In 2012, Gounardes, then just 27, was politically green. But he told The Bridge he felt Golden, who sometimes ran unopposed, “kept getting a free pass,” and that “no one was stepping up.” What’s more, Golden wasn’t satisfactorily addressing issues Gounardes was concerned about, like marriage equality, fair pay for women, elevator access at subway stations, and others, Gournardes said.

“No one thought I had a snowball’s chance in hell to win,” Gounardes said of his candidacy that year. “No one thought I could do better than 30%, and we ended up with just under 43% of the vote. We won this neighborhood of Bay Ridge by over a thousand votes; we were outspent nearly four to one.”

Gounardes’s strong showing was perhaps partly a result of his efforts in the community after Hurricane Sandy, which especially hit southern Brooklyn hard just a week before the election. On the night of the storm, he hunkered into FDR High School doing intake for displaced individuals seeking shelter. Then he went to Gerritsen Beach and spent three days knocking on doors to provide information about Red Cross assistance and to deliver food to those in need, mostly senior citizens. “I think I wiped out the sandwich counter at the gas station minimart like three or four times,” Gounardes said. “I, and so many others, felt compelled to do anything that would help.”

Later, he co-founded Bay Ridge Cares, an outreach group that was launched in the kitchen of St. Mary’s Antiochian Orthodox Church on 81st Street a couple days after the storm. “We had all these chefs who got washed out of their restaurants in Downtown Brooklyn, who had nowhere to go,” Gounardes said. “So they came to us and they started cooking meals for us that we then distributed.”

At the Dyker Heights debate, the crowd of about 100 was vociferous, often in support of the challenger (Photo by Trey Pentecost)

Gounardes helped secure a $5,000 grant from Citizens Committee for NYC, and over six weeks the kitchen dished out 25,000 hot meals to people in Coney Island, the Rockaways, Gerritsen Beach, and Staten Island. A few months after the election, wanting to continue the community outreach, he and Karen Tadross, a theater producer who’d initially secured the St. Mary’s kitchen space, decided to incorporate the nonprofit. They envisioned Bay Ridge Cares as “the neighborhood’s Red Cross.” The group has organized community breakfasts and Thanksgiving dinner deliveries, as well as pajama drives for the homeless and victims of domestic abuse.

“He’s smart,” Tadross said, praising the candidate’s problem-solving skills. “Whenever I hit up against a brick wall or was looking for a way to make Bay Ridge Cares happen, he was always there with quick answers, ways to do things, so I came to value his advice. He’s just got common sense, and that is so hard to find these days, especially in young people,” said Tadross, who’s 59.

The Party Rallies Around Him

Gounardes has benefited from New York’s constellation of Democratic stars, including the governor and both U.S. senators, who have showered endorsements on him. “Andrew Gounardes exemplifies what public service should be,” reads an endorsement from his boss, Borough President Eric Adams. “I know that because I’ve seen it firsthand at Brooklyn Borough Hall. He’s committed to empowering his neighbors, passionate about grassroots advocacy, and personally engaged with addressing critical issues …”

The New York Times editorial board endorsed him as well, allowing that Golden has been “a classic, affable politician,” but that Gounardes “would help end the obstruction to reform in Albany and would provide fresh energy in a stultified Senate.”

If he’s victorious, Gounardes plans to push for better pedestrian safety, particularly by placing speed cameras in school zones, which Golden, who has been issued 10 school-zone speeding tickets since 2015, opposes. Gounardes wants mass transit reform, with greater MTA accountability, and free, quality education, from Pre-K through college across the state. (Golden, who did not respond to an interview request for this story, has said that Gounardes’s prospective policies will be too costly for the state.)

In the realm of business, Gounardes’s website says he’ll do more to support small businesses by lowering the sales tax on items they sell and encouraging the development of more co-working spaces to ease costs for startups and freelancers. He’ll look to generate jobs with higher wages, and wishes to create “a local regional business council for Southern Brooklyn to support economic development, immigrant owned businesses, innovation, and bring 21st century jobs to Southern Brooklyn.”

The 22nd District stretches from the diversely populated neighborhood of Bay Ridge to mostly white, conservative neighborhoods to the East (Courtesy of Google Maps)

Like many legislative districts, the 22nd has been gerrymandered so that its shape is like that of a circuit board crafted by a deranged engineer. The equal-rights group Common Cause called it “the Marty Golden gerrymander” for the way the legislature stretched it to include decidedly conservative neighborhoods to strengthen the GOP’s grip on it. In 2016, outside of Staten Island, District 22 saw more people vote for Donald Trump than just about anywhere else in the city. That same year, Golden ran for his senate seat unopposed.

So on the surface, it appears, Gounardes and his left-leaning platform face an uphill battle. But since Golden has been in office, the district’s demographics have shifted. According to a CityLab story that analyzed data from the city comptroller’s office, between 2000 and 2015 the area has seen an influx of Asian-, Hispanic-, and African-Americans, all groups that tend to vote Democratic more frequently. The white population, meanwhile, has decreased.

Concerns about racial tension have come up in Gounardes-Golden debates. At the Dyker Heights stop, Gounardes mentioned that Golden has a checkered history with Arab-American relations—to which Golden called him “a liar”—and when a white audience member asked Gounardes if immigrants walk the streets of South Brooklyn “in fear” because they “came here illegally,” Gounardes spoke of various hate crimes in the area, which he denounced. “We’re all immigrants, we all came from somewhere else,” he said. (Golden is the oldest of eight children born to Irish immigrants.)

Gounardes wants the district’s power structure to become more inclusive of the newcomers. “You’re seeing the old guard that is incredibly outdated in their views, and in their connections to the neighborhood, desperately holding on to whatever they can,” he said. “Marty Golden’s machine has really kept Republicans employed here for a very long time, so [they’re] nervous about what’s going to happen to them when they lose.”

Why does he think that’ll happen this time around? “I’m a better candidate, I’m running a better campaign, and times are different.”

Apple Discovers a New Stage for Its Fanfare: Brooklyn

The event being planned for the Brooklyn Academy of Music was so hush-hush for awhile that BAM staffers were using a code name: Acme. By this morning, however, the secret was out. Crowds were lining up by the hundreds to see the latest announcements from a company that knows how to put on a show: Apple.

It was a historic event, the first time the company has staged one of its keynote product announcements in New York City, so it became almost as much a celebration of the location as the merchandise. “I am moving to New York!,” Apple CEO Tim Cook declared after a Brooklyn-sized roar from the crowd.

Brooklyn Academy of Music, site of the event, was festooned in Apple iconography

That’s not likely, since Apple has just finished building its new, $5 billion “spaceship” headquarters in California, but the company’s newfound affinity for Brooklyn as a creative hub was expressed early and often. The show included several nods to local culture, ranging from a performance by singer Lana Del Rey to a demonstration of a video game pitting the Brooklyn Nets vs. the Golden State Warriors on a new iPad Pro.

“I think it’s a really big deal that Apple chose Brooklyn for a launch event. So much of the creative class is here in Brooklyn,” said Regina Myer, president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, who said she was suitably wowed by Apple’s audio-visual mastery: “A flawless presentation.”

After the announcements, attendees trooped over to the lobby of One Hanson Place for some hands-on time with the updated devices

Cook and his colleagues unveiled a wave of product upgrades aimed at boosting its sales of computers and tablets, including the first redesigned version of the MacBook Air since 2010, sleeker and more powerful versions of the iPad Pro, and a five-times-faster iteration of the Mac mini desktop computer. All of the upgraded products carry higher prices as well, to keep Apple’s legendary profits chugging along. Last month, the company announced new versions of the iPhone (the XS, XS Max and XR) and its smartwatch. Among today’s announcements:

While iPhones now bring in two thirds of Apple’s revenues, an all-new version of its best-selling laptop, the MacBook Air, shows an abiding commitment to its Mac line. (Cook said that 100 million Macs are now in use.) The new version features Apple’s high-def retina display and Touch ID for the first time. It’s also thinner, lighter, and has less overall volume because its 13.3-inch screen extends nearly to the outer frame. The new MacBook Air starts at $1,199, up $200 from the current model.

Demonstrating the high-def display of the new iPad Pro, video-game makers showed a closeup of Nets star D’Angelo Russell

The top of the line iPad, the Pro model, has been revved up in multiple ways. Amid sagging sales of tablet devices, the new iPad Pro seems designed to compete with PCs and even gaming consoles. In two display sizes, 11 inch ($799) and 12.9 inch ($999), the new model packs more speed, power and memory into a smaller package. Other new features include Face ID, which debuted on last year’s iPhone X, and an updated Apple Pencil that attaches magnetically to the side of the device.

Sustainability was a big theme as well. The frames of the new MacBook Air and iPad Pro will be made from 100% recycled aluminum, creating a new custom alloy that Apple says it has engineered “down to the molecular level.” The MacBook Air is built with 100% recycled tin and 35% recycled plastic as well.

As part of its move toward sustainability, Apple makes the frames of the MacBook Air from recycled metals

In keeping with the overall theme of creativity, representatives from software companies showed what the new devices can do. Adobe reps demonstrated the graphic capabilities of the forthcoming Photoshop for the iPad, due next year, using the Pencil device to zoom in and out of an illustration at high speed. Take-Two Interactive Software touted the high definition of its NBA 2K game version for the iPad, displaying a close-up of star player D’Angelo Russell in such detail the audience could see the finer points of his tattoos and beads of sweat on his head.

Apple’s ballyhoo in Brooklyn today could well be a harbinger of things to come, with more events of national import occurring in the borough, said the downtown partnership’s Myer. “We’re going to have the venues to bring more and more great events to Downtown Brooklyn,” she said, citing the planned refurbishment of the LIU Brooklyn Paramount Theatre and a 1,000-seat auditorium in the new building at the New York City College of Technology (City Tech).

While waiting for the event to start, a group demonstrates with their smartphones why Apple has such a hold on its devotees