Where the Trucks Have No Home: a Battle for Space

To describe the Foster Avenue frontage road between East 83rd and East 87th streets as unremarkable is generous. On one side, imposing brick warehouse walls span entire blocks. On the other, a steady flow of traffic zips by on northern Canarsie’s main east-west thoroughfare. Litter and fallen leaves mingle in untended dunes, spilling over from the gutter onto the sidewalk. At night, streetlights cast a harsh glare that somehow makes everything feel even dimmer.

But this drab, fifth-of-a-mile stretch of roadway is the flashpoint in a rift between the Brooklyn Terminal Market, a neighborhood stalwart, and a group of truck drivers who say they’re getting short shrift from a newly accelerated policy of ticketing and towing tractor-trailers. While the roadside is designated a no-standing zone during overnight hours, it has long been used as a de facto parking lot for big rigs. But now, at the market’s request, it’s the target of an aggressive police crackdown on illegal commercial parking.

Ricky Ewers, 41, has been issued tickets in the stepped-up enforcement push on the service road outside the Brooklyn Terminal Market. “It’s really unfair,” said Ewers, who lives nearby and says there’s nowhere else in the area to park his truck overnight

Trucks are the lifeblood of the market, a major wholesaler of produce for stores throughout Brooklyn and beyond. On any given day, up to 200 tractor-trailers come through to load or unload goods at the market’s 29 vendors, according to Charlie Ciraolo, who heads the cooperative that owns and manages the space. (Ciraolo also runs Whitey Produce Co., a vendor at the market whose bright yellow bumper stickers proudly proclaim, OUR SPECIALTY: TEXAS WATERMELONS.)

The problem, Ciraolo said, is that trucks parked on the service road interfere with daily market operations. “They block traffic, so our trucks can’t get out,” he said. “And it’s not fair to our guys who drive all day and then there’s nowhere for them to park. It’s terrible. We want to be friends—we don’t want to be mean—but there’s nowhere for our trucks.”

NYPD traffic-enforcement agents prepare to tow a tractor-trailer parked on the service road

Richard Andrews doesn’t buy Ciraolo’s argument. The 39-year-old trucker lives just blocks from the market, where since 2000 he has picked up and dropped off produce and Christmas trees, always parking overnight on the service road, he said. “We don’t bother nobody,” Andrews said, adding he doesn’t have many alternatives. “There are no yards in Brooklyn. There’s parking at JFK, but it’s full. Why should I have to park in Jersey? I’m serving the market.”

The battle for street space outside the Brooklyn Terminal Market is just one piece in the citywide puzzle of remedying traffic congestion caused by trucks. Citing the environmental and economic impacts of semi-clogged streets—trucking congestion cost the city’s economy an estimated $862 million in 2017—the New York City Economic Development Corp. recently unveiled a plan, Freight NYC, aimed at drastically reducing the number of trucks on the city’s roads by 2045. By consolidating freight hubs and increasing the amount of freight carried via sea and rail, the plan aims to eliminate over 40 million miles of truck travel each year.

In Canarsie, that epic struggle for space is happening one truck at a time. On a recent brisk evening, Officers Yhayh Saleh and Matthew Mauro from the 69th Precinct were carrying through on warnings made the week prior, when they wrote tickets to truck drivers parked overnight and told them that future violators would be towed. The two directed a specialized heavy tow unit to the vehicles to be hauled to the Brooklyn Tow Pound at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The frontage road between Foster Avenue and the Brooklyn Terminal Market is the staging ground for a dispute between truckers, who have long parked there without incident, and the market, which has requested police enforcement to keep the road clear

Saleh and Mauro said they don’t find any joy in having trucks towed, but they see the enforcement as a necessary response to the market’s complaints. “It’s what the community wants,” Saleh said with a shrug. Asked if he had any unpleasant encounters during the operation, Mauro said he hadn’t. “The drivers are all gentlemen,” Mauro said, “but they can’t be here, and they know that.”

Pressed by drivers at a community meeting last month, the precinct’s commanding officer, Capt. Terrell Anderson, said his officers would schedule and mediate a summit between the market and the truckers. Drivers said such a meeting has yet to be set up. In the meantime, they’re looking for parking elsewhere.

A market employee uses a forklift to move a pallet of tomatoes from the back of a tractor-trailer. The market is a major wholesaler of produce for stores and restaurants across the city

Andrews pulled up in a sedan as the towers arrived. He had been tipped off by a fellow neighborhood trucker and came over to survey the scene, move his truck, and warn anyone whose truck he recognized that they were in danger of a tow. “I don’t know why these people are complaining,” he said, shaking his head, referring to the market. “We bring the food to the grocery store. We take your garbage to the landfill. And yet we’re still getting chastised because we park here.”

In all, three trucks were towed in the operation, the first in a series of tows to come, said the precinct. Art Rodriguez, 50, another market trucker, lamented the predicament he and his fellow drivers find themselves in. Despite providing an essential service, he said, they’re often castigated. “We don’t get a fair shot at all,” he said. “Help us out. You can’t buy things without us. If we stop moving, the world stops.”

A truck is towed by the NYPD. Trucks are brought to the impound lot at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where one trucker said it’s “a nightmare” to get the vehicle out

Brooklyn News Group Helps Spur NY Lawsuit Against Exxon

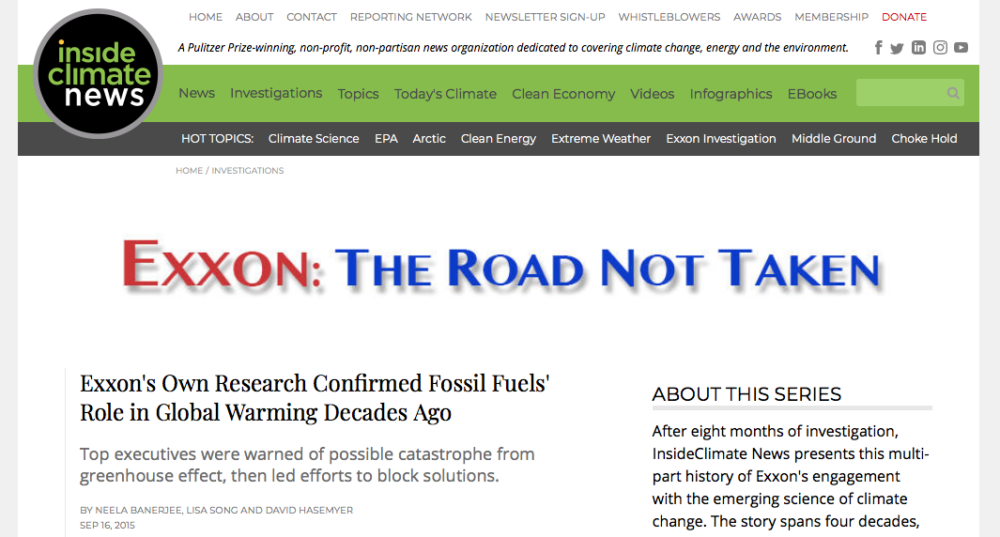

Did scientific confirmation of climate change sneak up on the world, with only a few lonely academics toiling away on the issue? Not hardly. In fact, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, cutting-edge research on climate change was conducted by none other than Exxon Corp. The oil giant even equipped one of its supertankers, the Esso Atlantic, as an oceanic laboratory to measure for CO2 in the air and water.

The company’s studies confirmed the role of fossil fuels in global warming, and Exxon researchers warned top executives of the potentially catastrophic effects. Then the company went into denial mode. “After a decade of frank internal discussions on global warming and conducting unbiased studies on it, Exxon changed direction in 1989 and spent more than 20 years discrediting the research its own scientists had once confirmed,” wrote InsideClimate News, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit news organization, in a groundbreaking series in 2015 titled Exxon: The Road Not Taken.

The impact of the series, which was a finalist for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service and the winner of a dozen other awards, was reaffirmed Wednesday when New York’s attorney general filed a lawsuit against the company, now Exxon Mobil, accusing it of defrauding investors by downplaying the financial risks the company faces as a result of climate change.

The InsideClimate News editorial team around the time the Exxon series was published (Photo courtesy of InsideClimate News)

“Exxon built a facade to deceive investors into believing that the company was managing the risks of climate change regulation to its business when, in fact, it was intentionally and systematically underestimating or ignoring them, contrary to its public representations,” Attorney General Barbara Underwood said in a prepared statement. In its own statement, Exxon said it “looks forward to refuting these claims as soon as possible and getting this meritless civil lawsuit dismissed.”

A team of InsideClimate News journalists spent eight months reporting their series in in 2015, producing an epic tale that spanned four decades and was populated by characters including Exxon scientist Henry Shaw, whose own children were steeped in their father’s global-warming research. “I knew what the greenhouse effect was before I knew what an actual greenhouse was,” David Shaw, Henry’s son, told the reporters.

InsideClimate News published its series in September 2015. The following month, the Los Angeles Times published its own series on global warming and Big Oil, reaching similar conclusions. In November of that year, news of New York’s investigation broke when then-Attorney General Eric Schneiderman issued a subpoena to Exxon Mobil, demanding extensive documents.

The nine-part series was also published as an e-book and paperback

After the New York lawsuit was filed this week, InsideClimate News founder and publisher David Sassoon told The Bridge: “Our team was awfully proud yesterday. The lawsuit is a direct result of work our small, non-profit newsroom published three years ago about one of the most powerful companies in the world. Who says journalism doesn’t matter anymore?”

InsideClimate News, which has offices in Downtown Brooklyn and reporters in other cities, started in 2007 as a blog by Sassoon and co-founder Stacy Feldman. In 2013, the growing organization won the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for its series The Dilbit Disaster: Inside the biggest oil spill you’ve never heard of.

The news organization, which describes itself as non-partisan in its coverage, supports itself through donations from foundations and its readers. What was once a blog is now staffed by seasoned journalists recruited from the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, ProPublica, Los Angeles Times, and Bloomberg News.

Even with such a pedigreed staff, it all comes down to the effort, says Sassoon. “It requires hard work and dedication to produce a nine-part series like we did. It’s how we work every day, and how journalists around the country work every day. That’s the most important thing to remember.”

The news organization produced this video last year to mark its 10th anniversary (Video courtesy of ICN, via YouTube)

Editor’s note: In 2017, InsideClimate News co-published The Bridge’s story on the effects of climate change on one Brooklyn neighborhood, Red Hook vs. the Rising Tide.

Inside RLab, a Place to Create Virtual New Realities

I reached out and touched a human cadaver yesterday, using a scalpel to dissect a deltoid muscle. I might have been more squeamish about the experience, but this was not a human body of the deceased kind. It was a corpse created in virtual reality, viewed through a VR headset. Yet it was vividly real.

“It’s intended to replace cadaver dissection, because that’s kind of expensive,” explained Sam Seidenberg, a software engineer for Medivis, a Brooklyn-based company developing an educational product called Anatomy X. “You still get the same three-dimensional exploration without having to deal with an actual human cadaver.”

Seidenberg and his company were among 30 exhibitors demonstrating their projects at the launching of RLab, the first city-funded lab in the U.S. dedicated to virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR). When completed next year, the lab will house 16,500 sq. ft. of co-working labs, classrooms and studios in a former manufacturing building in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

At the launch event, hundreds of visitors tried on headsets to get a sense of things to come, inspiring many waving arms and swiveling heads as they explored virtual worlds ranging from construction sites to medieval sword fights.

A dancer wearing motion-capture sensors spun around to create a 3D recording

In a nearby space, a dancer/technologist spun about in acrobatic patterns, her body fitted with motion-capture sensors to enable a computer to record a 3D rendering of her movements. The exhibit was the work of an NYU class that seems to represent the kind of cross-disciplinary creativity and community that’s expected to thrive at RLab. The class brings together both engineering and art students, who learn motion-capture techniques, graphics rendering, and the conceptual development to create stories in VR, said class’s instructor, Todd Bryant.

If the new lab is a success, it will have many beaming parents. It represents a $6.5 million investment by the New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYCEDC) and the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment (MOME), and will be administered by Brooklyn’s NYU Tandon School of Engineering, with a participating consortium including Columbia University, CUNY and The New School.

Julie Menin, commissioner of the Mayor’s Office and Media and Entertainment, said the new lab will help create jobs by providing “a pipeline into these fields”

Super Ventures, an early-stage fund for VR/AR ventures, will support startup companies in a business accelerator program on the site. “This is a product of years of work by many, many individuals,” said Justin Hendrix, executive director of the NYC Media Lab, who will serve as RLab’s interim executive director.

Several of the speakers at the event emphasized that, while many projects are already underway for the site, it represents an incubator for ideas that haven’t been hatched yet. “This is a really proud day for NYU Tandon and all our partners,” said the school’s new dean, Jelena Kovačević. “This will be the epicenter for things we can’t even contemplate today.”

Mary Boyce, dean of Columbia University’s Fu Foundation School of Engineering, did offer a sneak preview that VR/AR enthusiasts will welcome. Researchers at her school are working on new materials and optics to make VR/AR headsets less cumbersome, she said.

A willing participant in the VR version of Knightfall, a History Channel series about the Knights Templar. The game will be deployed for “location-based experiences,” for example in the lobbies of Imax theaters, said Timothy Call, a senior director of multimedia for A+E Networks

For the Navy Yard, RLab will provide a kind of greenhouse for producing new ideas, startup companies and trained workers to help fulfill its plans to grow in the next few years from 9,000 employees at 400 companies to 20,000 people at about 1,000 companies.

“We’ve been trying to woo NYU to the Navy Yard for quite some time,” said David Ehrenberg, the Navy Yard’s president and CEO, who recounted the yard’s evolution from building battleships to creating tech-driven products. “We don’t know what will take off, so we try to create a diverse ecosystem.”

When completed next year, the 16,500-sq.-ft. space will provide labs, studios and classrooms on the third floor of Building 22 in the Navy Yard

The takeoff of VR/AR seems well underway. “Investors have poured $7.2 billion into XR startups in the last 12 months alone,” said Ori Inbar, founder and managing partner at Super Ventures, who helpfully explained that the term XR, or extended reality, is becoming a kind of umbrella term for virtual-, augmented- and mixed-reality technologies. “Every once in a while a new technology revolution comes along that changes everything. XR is ready for explosive growth,” he said, adding, “NYC has all the ingredients you need to be the epicenter of XR.”

Much of the city’s motivation for backing the venture is about creating jobs. Mayor de Blasio, in his 2017 New Yorks Plan, committed to creating 100,000 good-paying jobs over 10 years, including 30,000 jobs in tech fields.

Indeed, while many of the initial applications of XR are in the realm of fun and games, many of the exhibitors at the RLab opening showed apps that are being embraced by mainstream industry. InsiteVR, for example, is developing a digital platform for the construction industry that allows architects and engineers to walk through planned buildings together, even if they’re dialing in from far-flung continents.

Even the field of journalism may benefit as it strives to reinvent itself. “We are seeing tremendous interest from journalism organizations in experimenting with VR and AR,” said Sarah Bartlett, dean of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. “We’re excited to help expand the community that participates in that experimentation.”

Perhaps the most epigrammatic thing said during the heady event was from Inbar, who emphasized the reality-based aspect of it all: “XR isn’t about technology, it’s about life.”

Cooked: Inside the Sudden Fall of a Business Incubator

Standing next to a walk-in refrigerator that held plastic bins packed with perishable food, entrepreneur Adriana Jaramillo was still in disbelief as she recalled the tense Saturday afternoon when she and her fellow Pilotworks members were asked to leave the premises.

“I understand they don’t have money, I understand they have to close the business. Why I’m mad, is the way they did it,” says Jaramillo of the owners of Pilotworks, the commercial kitchen billed not long ago as a “WeWork for food startups,” which housed an estimated 175 small companies.

Given that the company had raised $13 million in venture-capital funding only last December from big-name companies like Campbell’s Soup, the fall of Pilotworks was not only sudden but mysterious. On the afternoon of Oct. 13, the company’s director of operations, Tessa Price, entered the second-floor, 10,000-sq.-ft. kitchen and ordered the members on hand to leave, according to Jaramillo.

“She said you have two hours to pack everything … and if you don’t go easy, we call the police,” says Jaramillo, a 57-year-old immigrant from Colombia. With their paid membership to the Pilotworks community kitchen—about $5,000 a month, which bought them 40 hours a week of kitchen time—Adriana and her son Sebastian had been able to run their own Latin-cuisine catering company called Mi Casa Foods.

By last week, members had hauled away their raw materials and left only idle equipment (Photo by Michael Stahl)

Adriana says Price was “very mean” and “rude” as she spoke to the other members, who at that point had received no prior notice of the kitchen’s shutdown. An email would be sent to all Pilotworks members at 6:42 p.m., informing them that the company was out of business. The members had until the following Wednesday afternoon to clear out their belongings. Several members told The Bridge that less than a week earlier they had paid a month’s rent, which could run between a few hundred and a few thousand dollars.

On the final day they’d be allowed to fetch their stored food—frozen beef, boxes of bananas, trays of carrots, containers of chopped celery, and much more—Adriana and a tiny contingency of her dazed small-business colleagues were gathering what they could, frantically looking for alternative kitchens, and angrily questioning how the company could have mismanaged its money so badly.

Given that $1.3 million in public funding was spent on the company’s initial startup, elected officials wanted to know too, calling for an investigation into the collapse. Based on interviews with members and former employees, The Bridge offers an emerging picture of how a venture with so much momentum suddenly came to a halt.

A Duo In Search of a Killer Idea

As of January 2017, the principal owners of Pilotworks were Nick Devane and Mike Dee, close friends in their 20s who had yearned to find the right startup idea. About the time they finished college in 2013 (Wesleyan and Georgetown, respectively), the duo started Grazer, an app that allowed home cooks to make money cooking meals for their neighbors. The idea was that it wold create “a marketplace for homemade food” and a community among chefs and customers.

The bootstrapping entrepreneurs—Dee was sleeping on Devane’s couch at the time—also opened Zulu’s Coffee Shop, an all-cold-brew establishment on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Both companies quickly folded, but after connecting with Alex Iskold, managing director of the New York City branch of Techstars, a network offering mentorships and investment capital to startups, Devane and Dee were admitted into a program for developers-in-residence.

Nick Devane was the company’s co-founder and the CEO until he stepped down in June (Photo courtesy of Pilotworks)

Utilizing what they learned in Techstars in the summer of 2015 and, according to an interview with Devane, getting a $120,000 investment from Iskold, the duo re-launched Grazer, re-branding it as “Homemade” and promoting it as “the Airbnb for cooking.” (Shortly thereafter, the pair were also given a $100,000 convertible note from Right Side Capital Management.)

But Homemade didn’t last long either, partly because it is illegal to sell food without appropriate permits in New York State, which some of the app’s household chefs hadn’t obtained. (Devane also claimed in Fast Company that Homemade went under because production was limited and chefs frequently broke off to start their own operations.)

After shuttering Homemade, Devane and Dee used leftover proceeds to buy a subsidiary of another floundering company called Dinner Lab, which produced one-off dining events in various cities around the U.S. and, according to a Forbes story in May 2016, “blew through $10 million.” Dinner Lab was the operator of Brooklyn FoodWorks, a “licensed shared kitchen and culinary incubator,” which had opened in an old Pfizer pharmaceutical plant at the base of the Broadway Triangle in Bedford-Stuyvesant in February 2016.

Mike Dee, co-founder of the company, served for a time as chief technical officer (Photo courtesy of Pilotworks)

That venture had been made possible in part by $1.3 million in funding from the New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYCEDC), allocated with the blessing of Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and City Council Member Robert Cornegy Jr., who represents the district where the Pfizer building stands.

“The incubator will provide various personalized business mentorship and programming offerings designed to address crucial aspects of creating sustainable businesses, including branding and marketing, product liability and insurance, early stage financing, and distribution,” said an NYCEDC statement announcing the Brooklyn FoodWorks founding. “Additionally, Brooklyn FoodWorks will be a home for local food discussion and innovation and will host a variety of regularly-scheduled networking events, tastings and social gatherings that will be open to the public.”

Over time, the space became a welcoming hub for small businesses run by women and minorities, which made up the majority of its members, and helped make the Pfizer building a hub for food-and-beverage startups. Purchased in 2011 by Acumen Capital Partners, which did not respond to a request for comment, the refurbished Pfizer building became home to the likes of McClure’s Pickles, Brooklyn Soda Works, and other food-industry up-and-comers.

Devane and Dee eventually shortened the venture’s name to just “Foodworks” and later “Pilotworks” as they launched a plan to rapidly scale up by opening outposts around the U.S., fueled by more than $15 million in total venture capital, acquired from around 20 investors over four rounds of fundraising. The two became stars of the startup world, recognized on Forbes’s 30 Under 30 list last year.

In September 2016, Pilotworks acquired an incubator kitchen in Portland, Maine, followed by a grand opening in Providence 15 months later. Then, within the first five months of 2018, Pilotworks accelerated its growth by opening kitchens in Dallas, Chicago and Newark.

But now all but the Portland kitchen, which reopened under new management, are gone.

A Yen for Spending

Standing in the empty kitchen last week, one member who didn’t wish to give his name pointed to a piece of new equipment, a top-of-the-line commercial blender/mixer he said cost $18,000 and was not needed in the kitchen at all. (Sebastian Jaramillo of Mi Casa Foods told The Bridge he’d heard it was ordered accidentally after the company had already purchased another.) The blender/mixer stood unopened on a delivery pallet in its box.

“The way they fucked everyone over is just …” the member says, unable to finish his thought about Pilotworks’ management. “And they just took off.”

The team behind the family business Mi Casa Foods, who were among those who lost their home base (Photo courtesy of Mi Casa Foods, via Instagram)

Gothamist, which had obtained a copy of the membership contract, reported that the company had agreed to give its members 10 days’ notice if the company wished to terminate it. Eater reported that some Pilotworks members, who have not been able to contact the company’s management, are owed anywhere between $2,000 and $15,000 in outstanding payments from the distribution arm.

Last Wednesday, this reporter rang the bell to the Pilotworks office on the Pfizer building’s third floor but got no response, though chatter could be heard through the glass doors. Tessa Price, Mike Dee, and Zach Ware—the Pilotworks CEO, who took over in June—did not answer requests for comment from The Bridge, nor have top managers, including Nick Devane, made themselves available to the media. Instead, via a now defunct email address, a representative named Kirk Love directed The Bridge to the company’s statement on its website.

“It is with a heavy heart that after failing to raise the necessary capital to continue operations, Pilotworks will cease operations,” the statement reads. “This is a sad outcome for Pilotworks, the makers in our kitchens, and independent food in general. We wish there was another option to continue operating. Sadly, there was not.” The note was signed, “Regretfully, Pilotworks.”

The note left everyone hungry for an explanation. Prospective investigators will have plenty to sift through. In the mean time, multiple sources who spoke to The Bridge say that the widely speculated notion that the company simply expanded too quickly is just part of what went wrong.

“There were so many issues relating to how they spent their money,” said a former management-level employee who had signed a non-disclosure agreement upon being asked to leave the company and, thus, wished to remain anonymous. “There was a big tech team [that] worked on making a member portal where members could have a community board, but basically a lot of functionality that they made was completely unnecessary, and you could’ve gotten it from third parties.”

The source said there was no dialogue between the tech team and the members, nor did members think they even had a need for a tech team. “They were spending an insane amount on salaries for these people, which had nothing to do with the workings of the kitchen,” the source asserted about Devane and Dee.

An the deserted Pilotworks, an expensive mixer/blender was still in its box. Members said it was an unnecessary expense (Photo by Michael Stahl)

Nick Devane was so “reckless with spending,” according to the source. He “wanted to move to L.A. because he liked surfing, and he tried to acquire a kitchen in L.A., but even when it didn’t work out, he opened a very expensive office in Venice.” (Little public information about such an office is available online, though one LinkedIn profile of a Los Angeles-based sales and outreach worker for Pilotworks notes the company’s presence in the city.) The source also said that Devane “got a company apartment in L.A.”

Over time, all of the previous staff from Brooklyn Foodworks were either fired or quit, the latter because, Sebastian Jaramillo said, they were poorly treated by the Pilotworks head honchos. Jaramillo also told The Bridge that, in meetings with Devane, he heard him describe the business model of Pilotworks in terms far different from its stated purpose of being a nourishing business incubator. “We can run it like a gym model: people sign up, most people won’t use most of their time and we can just cash in,” Jaramillo recalls Devane saying.

During the company’s burst of expansion, signs of strain began to show. In February, Zach Ware, a veteran of Zappos and Republic of Tea, was hired as the chief operating officer after a week of consulting for the company. In June, Ware stepped up to CEO while Devane stepped down from his leadership role to focus on “long-term creative and strategic initiatives,” according to a company statement, and has been living in Los Angeles.

By at least one account, Ware didn’t exactly impose stringent cost controls. According to the former management-level employee, Ware utilized company funds in “refabbing a lot of the kitchens because he wanted each kitchen to have the same layout … which I don’t think was necessary at all.”

Anke Albert, who owns Anke’s Fit Bakery and was clearing out her belongings from Pilotworks last week, said, “People had a feeling something was off with Pilotworks.” Albert founded her company in the Hamptons, where she still utilizes another kitchen to make her healthy baked goods. After her recent expansion into Pilotworks, she got a 40% boost in sales this year, which she fears could be flushed away. Like other members, Albert wonders whether Pilotworks expanded too fast, especially since the company hadn’t really mastered the maintenance of its Brooklyn kitchen. Equipment would break and not get fixed quickly; the distribution service was inefficient and slow, she said.

Was It Ambition, or Pressure?

What was Devane thinking, as the company rose and fell so quickly? “In my impression of him, I don’t think there was any intention of hurting any business, and I also don’t think in his mind there was any possibility that they were going to fail,” said April Wachtel, a former Pilotworks member and founder of Swig + Swallow, which produces bottled cocktail mixers. Wachtel is sympathetic to the plight of the Pilotworks members—after all, she’s one of them, and in the wake of the kitchen closing has built supportindependentfood.com to assist Pilotworks vendors in making helpful connections.

However, Wachtel told The Bridge she considers Devane a friend, and got to know him fairly well, especially after interviewing him on her podcast, Movers and Shakers, where he paints the classic picture of a kid who “grew up pretty poor” and toiled through lean years as he tried to make a name for himself in business and tech. Wachtel said there’s a chance Devane didn’t initially know about the legal ramifications of the Homemade model, and, in the early days of Pilotworks, excitement about the company was abundant in the kitchens.

A member of the facility at one of its 16 workstations, back when it was still called Foodworks (Photo courtesy of Foodworks)

But when nearly two dozen investors sink more than $15 million into a business, they tend to want to see growth. Still unclear are the promises that Devane and Dee had made in that regard, or what pressure investors put on them to expand. What’s more certain is the duo had no previous experience at growing a business on that scale.

In a text, Wachtel wrote: “I just like to look for the learnings and positive ways to move forward. For me personally, the learning has been we will mostly not speak to VCs anytime soon and will try to raise from [angel investors], as this shows what [venture capitalists] can do to your business if you’re not ready to scale as quickly as they need.”

Acre Venture Partners, the capital investment arm of Campbell’s Soup, one of the lead investors in the Series A funding round for Pilotworks, declined to comment for this story. On Twitter, Alex Iskold of Techstars, which wound up being a second lead investor in that same funding round, appeared nonplussed by the shutdown, writing: “I am the luckiest guy to be an investor in 100 incredible startups. Nick Devane, Mike Dee and @PilotworksHQ will always have a special place in my heart. The journey ends but memories, inspiration and idea lives on. Thank you for everything Nick and Mike!”

Now the doors are closed for good, unless a rescue can be engineered (Photo by Michael Stahl)

VCs tend to see a lot of flameouts. They go with the territory. But forgiveness and farewells don’t come as readily to the small-business owners affected by the kitchen’s closing. “Most people had to cancel all their orders for the week,” Sebastian Jaramillo says. After Pilotworks tossed his mother, Adriana, out of the building, the Mi Casa Foods tandem hurried to another kitchen space they found through their network and cooked through the night.

They were able to complete the order they were working on at Pilotworks, which was due the next afternoon, but called clients who’d placed orders for the next two weeks and told them they couldn’t deliver. “This is an incredible hit to a small business. For us, it’s $5,000 this week alone,” Jaramillo said last week.

Jaramillo, 29, had earlier been a co-founder and the kitchen-operations manager at Brooklyn FoodWorks. He helped design and build the second-floor kitchen, but soon after the Devane/Dee takeover, Jaramillo, unhappy with the way they were running the company, decided to leave his post and run Mi Casa Foods with his mother.

“This is my full-time job, this is my hustle. We took out business loans, we bought a car in order to make deliveries,” he says. “We sold $10,000 last year, we’re about to crack $150,000 this year.” They’d been making their signature empanadas by hand—from a three-generation-old family recipe—and producing about 200 a day. Then they were able to buy a machine that allowed them to cook 600 empanadas an hour. “We’re truly growing, and we were just stopped dead in our tracks,” Jaramillo says.

The Local Economic Fallout

Jaramillo estimates, conservatively, that the Pilotworks shutdown threw 500 jobs into peril across all the small businesses that worked out of the community kitchen, both the second-floor space and a 7,000-sq.-ft. facility on the fourth floor. For the politicians who backed the organization in its initial Brooklyn FoodWorks iteration, it’s a public debacle they’re anxious to fix.

City Council Member Robert Cornegy, who supported the original incubator’s opening in February 2016, was conspicuously frustrated about the situation in a phone interview last week with The Bridge. “I hate that we have to have this call, but it is what it is,” he said. “The cost of commercial space in this city has skyrocketed exponentially over the last two decades. The average entrepreneur, who we’re asking to come out of their basements, their kitchens, their garages, and become part of a vibrant economy, we were able to do that through this program. I was really proud of it, and proud that it was in my district, so to see it be disbanded in this way is a little disheartening.”

In a joint statement with Borough President Adams released Oct. 16, Cornegy added: “It is our hope that NYCEDC, who has overseen this project since its initial inception, will work to find another shared commercial kitchen operator to operate this incubator for the affected food manufacturers who have relied on this space for their businesses’ well-being.” Cornegy also said he still believes that private-public partnerships are “a new model” of good, local business development, and he had hoped that Brooklyn FoodWorks would emerge as an example for similar, future ventures to follow.

A year ago, the incubator was decorated with a playful spirit (Photo by Angelica Frey)

“Over the last two days I’ve focused my attention on trying to save these vendors,” Cornegy said, adding that he expects a “thorough investigation” into “fiscal malfeasance” at some point. Cornegy said he plans to speak about a prospective probe with the Council Member from District 15, Ritchie Torres, who is chairman of the Council’s committee on oversight and investigations.

Members not only need to find new kitchens, but also new means of distribution. Laura Shafferman, who founded Legally Addictive, which produces a chocolate-toffee-cracker treat, was once a tenant in the kitchen, but at the time of its closing solely utilized the Pilotworks distribution service. She said it had helped garner new customers, but just as her business’s most-important quarter of the year—the holiday season, vital to so many other companies—was beginning, Pilotworks failed her.

“I have no clue how this is going to go,” Shafferman said of the situation. “It’s a significant portion of our business, and now I’m scrambling to get in touch with all of our customers, hoping they’ll work with us directly; I’m trying to absorb all the dropped shipping that’s happening. And of course there’s the loss of payment from some of the invoices that were still outstanding.”

Shafferman said she had reasons for optimism, though. She is impressed with the fact that displaced Pilotworks residents have banded together and helped each other in procuring kitchen space and other opportunities. Equally encouraging is that other businesses have offered to help in any way they can. Shafferman said a staffer at Eataly, who subscribes to her newsletter, reached out to say, “We’ve got jobs available; if anyone in the kitchen doesn’t have a job send them to us.”

Hot Bread Kitchen, a shared commercial kitchen space in East Harlem, opened a hotline and set up a digital intake form for Pilotworks members so they could serve as matchmaker in finding a suitable kitchen for them, either in East Harlem or at other kitchens in their network. “I have a lot of empathy for what it takes to run a small business,” says Shaolee Sen, Hot Bread Kitchen’s executive director. “Just knowing that everybody would be in a scramble and having to contact a bunch of different places to find help immediately, we said we would set up this hotline so they could have one point of contact.”

Greene Grape Annex, a café in Fort Greene, offered its space for a group meeting for those affected by the closure, as did the Moore Street Market, an East Williamsburg indoor market sustained by the NYCEDC, which saw a session organized by Brooklyn Quality Eats last week.

All this outreach and support more accurately reflects what, to many, the Pilotworks kitchen was supposed to be about. “I was here from the beginning,” said Adriana Jaramillo last week as she emptied out the Mi Casa Food storage at Pilotworks.

“I love our business, our community,” she said. “I love this kitchen.”

Small Businesses Need a Boost. Is This Law the Answer?

So you opened a small business in the neighborhood where you’ve lived since you were a kid. Maybe it’s in East New York. Because your roots are so deeply entrenched there, because you understand what your neighbors want and need, your dream business takes off. Could be a corner store, a hair salon, a day-care center, a bar or restaurant. Over the course of the ten-year lease on your storefront, you’ve built up a community of regulars and enjoyed plenty of walk-in traffic from newcomers to the neighborhood. You’ve hired a staff of three full-time employees so you can have dinner every night with your kids. Maybe you’ve started socking money away for a down payment on a home.

But now, 10 years later, your lease is up for renewal. And because East New York has become one of the fastest-developing neighborhoods in the five boroughs, commercial rents in the area have been on the rise. Your landlord, with whom you’ve had an amiable relationship for years, is demanding a rent increase you can’t afford—at least not without jacking up your prices to the point where you’ll scare away your customers. “It’s not personal,” the landlord tells you.

You consider laying off your employees—mothers and fathers themselves. You think about reopening elsewhere, but with no assurances your business will translate in another neighborhood. You also contemplate the grim option of closing the business altogether, with the prospect of seeing a cash-flush business—perhaps a national chain—occupying the space you’d built into a local institution.

In April, elected officials and community leaders rallied on the steps of City Hall in support of the SBJSA (Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation/Flickr)

Melodrama? No, a sadly common situation, according to proponents of the Small Business Jobs Survival Act (SBJSA), which they hope will provide a remedy. First proposed in the City Council over 30 years ago, the SBJSA would provide protections for small-business owners in their lease renewal negotiations. Among other conditions, it would require commercial landlords to inform their tenants 180 days in advance of a lease expiration whether they intend seek renewal. (The provisions of this chapter apply to any landlord and current tenant whose lease expires on or after Jan. 1, 2019.)

If a landlord doesn’t wish to do so, they’d have to provide valid reasons as to why, such as late rent payments or a history of criminal activity on the premises. If the tenant is in good standing, they’ll automatically qualify for a new 10-year lease, and if a rent rate cannot be agreed upon between the tenant and landlord, an independent arbitrator will establish one for them.

The SBJSA, which is currently being reviewed in the City Council’s Committee on Small Business, will get a hearing at City Hall on Mon., Oct 22. A preceding rally organized by the advocacy group Friends of the SBJSA will take place on the landmark’s steps at noon. While the legislation has been in limbo for three decades, the current City Council speaker, Corey Johnson, vociferously supports the bill, and its proponents are making a last-ditch campaign for it.

“This bill is going to save small businesses,” Friends of the SBJSA founder David Eisenbach told The Bridge. “It will stop the extortion; it’ll stop the massive turnover and turnout of mainly immigrant-owned businesses, which is what we’re seeing particularly in neighborhoods that have been rezoned.”

While small business has been under strain because of rising rents, an increasing number of chain stores have taken their places (Illustration by Heather Jones. Photos by Arden Phillips)

The northwest corner of Brooklyn, including Williamsburg and Greenpoint, famously underwent a rezoning 13 years ago, leading to a wave of rent hikes in both the residential and commercial sectors. According to commercial real-estate market reports published by TerraCRG, a brokerage firm that focuses on Brooklyn commercial properties, between 2010 and 2017 the average price per square foot of retail space in Williamsburg and Greenpoint went from $166 to an astronomical $1,710.

While that’s on the extreme end compared with other parts of Brooklyn, rising rents citywide have brought economic pressure on small businesses to the point of squeezing out their profit margin. The failure of such businesses has contributed to a new kind of urban blight: empty storefronts in prospering neighborhoods. Last month the New York Times cited a study showing that 20% of all retail space in Manhattan is currently vacant, up from about 7% from just two years ago.

City Council Member Rafael Espinal, who helped push through rezoning legislation for East New York, part of the district he represents, supports the SBJSA as “the first step in addressing the vacancy crisis head-on,” he told The Bridge in an email.

“I’m committed to finding even more legislative solutions to address the skyrocketing rents and commercial tenant harassment that so many small business owners face,” Espinal wrote. “Keeping our local shops open helps keep our neighborhoods affordable, and build a sense of community.”

The case for the bill is not just an economic one, according to many supporters, but an aesthetic and cultural one as well. “What I like about the SBJSA is the positive impact I believe it will have on small business people and the streetscape of the city,” Jeremiah Moss, author of Vanishing New York, the book and popular blog about the city’s ever-changing landscape, said in email. “The bill gives existing commercial tenants in good standing a few basic rights,” Moss continued. With it in place, “a landlord can’t just refuse to renew a lease, as they often do today. They can’t just double, triple, quadruple the rent, as they also often do today.”

Moss also noted that the bill protects small businesses of many varieties, from ground-floor retailers to manufacturing tenants to artists renting a penthouse loft. Moss also wrote that he works as a psychotherapist and “lost my office space to a luxury developer.”

Indeed, while the prospective beneficiaries of the bill are typically portrayed as established mom-and-pop shops, a newer generation of entrepreneurs has a stake in the issue as well. Says Max Friefeld, CEO of Voodoo Manufacturing, a 3-D printing company in East Williamsburg: “Small businesses and manufacturing are the foundation of any strong local economy. We’re excited to be in New York City, employing New Yorkers, and we want to stay.”

An Opposition Argument: It’s Not Legal

The reason the SBJSA has languished without passage in the City Council for so long, according to its supporters, is staunch opposition to the bill from “Big Real Estate,” typically personified by the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), the industry’s leading trade association. In a statement emailed to The Bridge last week, John Banks, REBNY’s president, said that the SBJSA is “illegal and ignores market conditions.”

“Vacancy rates fluctuate among individual retail corridors and rents are, in general, decreasing,” his statement continued. “The Council should focus its limited time, energy, and resources on solutions that will support small businesses instead of wasting millions of tax dollars defending an illegal bill that experts agree will be thrown out by the courts.”

Among those experts would be the New York City Bar Association, an organization of 2,400 lawyers and law students, which recently published a report that called the SBJSA “commercial rent control” —a label frequently used by the bill’s detractors in the press. The bar association committee that studied the bill determined that the city would be empowered to pass such legislation only by a concern for “health and welfare” and that “previous attempts by the City Council to enact residential rent controls–which the committee maintains are closer to concerns of health and welfare than are commercial rent controls–have already been struck down by the courts.”

Other opponents of the SBJSA object to the way the law is written. In an op-ed for the Commercial Observer, Steven Kirkpatrick, a member of the bar association, slammed the SBJSA for its lack of clarity on the origins of funds for prospective arbitration hearings, as well as its ignoring of the spectrum of commercial-tenant types. “So, a national retail chain store is granted new property rights and powers under the act just like the neighborhood pizzeria,” Kirkpatrick wrote. “Never mind what the landlord desires to do with her property. Under the act, the commercial tenant calls the shots.”

What Was the Original Intent?

Those in favor of the SBJSA say the measure is definitely not “commercial rent control,” including Ruth Messinger, the former City Council member and Democratic Party nominee for mayor. In 1986, when she represented the Council’s 4th District, Messinger wrote the initial version of the bill that has since been altered. She recently told The Bridge that, back then, “There was already an acute issue [with] small businesses establishing themselves, sometimes over three years, sometimes literally over 30 years, and all of a sudden running into the end of a lease at a point in which building owners felt—I think, largely correctly—that they could get much more for the space.”

Building owners asking for triple the rent on a new lease was one thing, but Messinger says a larger concern was the commonality of landlords only informing their tenants of a looming hike just prior to the lease’s expiration. “Because what they wanted was to get the existing tenant out in order to attract a new tenant,” Messinger says of landlords at the time. “I would say in most instances when the demand for a rent increase was huge, they knew that the tenant wouldn’t be able to pay, and they intensified that likelihood by telling them [shortly] before their lease was up.”

Rather than attempting to dictate rental rates, “it was a bill for binding arbitration in commercial-rent disputes,” Messinger says. “It required a back-and-forth negotiation [between the tenant and landlord], and maybe they would come to a meeting of the minds, but if they didn’t, they would go to an arbitration panel.”

Kirsten Theodos, a member of TakeBackNYC, a small-business advocacy group that has thrown its full support behind the SBJSA, and who recently wrote an op-ed for The Villager about the bill, worries that it could fall victim to mislabeling. “If it’s already being framed as something it’s not—‘commercial rent control,’” she told The Bridge last week, “it kind of makes you wonder, how fair is this hearing going to be?” Theodos argued that if the legal “nonsense” about the SBJSA is not refuted, the hearing will “revolve around the ‘legality’ of the bill, and we’re not going to have time to discuss real solutions.”

Whatever course the hearing takes, Eisenbach, who’s running for Public Advocate next year, believes that if the bill doesn’t pass through the City Council this year, it won’t get another chance for a long time, if ever. “I think this is the year. This is the window of opportunity and it really must be done now because we are losing so many businesses at an alarming rate,” Eisenbach said. “It’s really about the soul of the city. The loss of the small business is the loss of the character of our neighborhoods, the loss of the New York we all fell in love with.”

5G Wireless Is Coming! OK, What Exactly Does That Mean?

You’ve probably heard some of the hype: if you thought 4G wireless was great, you won’t believe 5G. In fact, the next generation of cell-phone service is already being launched in several U.S. cities. But how does it work? What makes it faster, better, and more efficient than what we’ve got now? And is there a wireless world even beyond that?

As it happens, answers to these questions can be found in Brooklyn, where NYU Wireless, an academic research center at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, is a world leader in the field. The program’s founding director, Prof. Ted Rappaport, just recently won the Radio Club of America’s Armstrong Medal, a prestigious award given for excellence in the field. (Going back in history, Walter Cronkite was a previous winner.) At about the same time, NYU Wireless received the largest grant in its history, a donation from Keysight Technologies that includes an array of cutting-edge equipment to help the school further its pioneering research.

The Bridge spoke with Prof. Rappaport about 5G’s capabilities, how it will affect our lives, and what comes next:

How did you personally get interested in the field?

When I was 5 years old, my grandpa showed me his Philco shortwave radio, and we tuned around for hours listening to ship-to-shore and Morse code. I’ve been hooked on wireless ever since. In college, my PhD research was the first to consider wireless data communications in factory buildings. This work helped develop the world’s first WiFi standards.

How would you describe 5G to someone who is unfamiliar with the term?

5G is the fifth generation of cellular telephone technology. The first generation occurred in the 1980s, using analog FM and was used mostly just for voice phone calls. The second generation of cellular (2G) was the world’s first cellphone system that sent digital signals over the air, obtaining greater capacity and supporting more cellphone subscribers as the industry grew at 100% subscriber growth per year. 2G is when texting was first used, and Europe, Asia, and the U.S. were split on their choice of technology, so that phones could not operate easily around the world.

The third generation of technology (3G) achieved more efficient use of the radio spectrum, supporting the 30% annual customer growth that occurred throughout the late 1990s and 2000s, and early internet browsing was supported, although it was clunky. And still the world had not unified its technology choice, with two main competitors: a Qualcomm-based CDMA technology, and a European-based UMTS technology that derived from the European GSM standard of the 1980s.

4G is when the world unified the technology choice, standardizing on LTE for phones around the world. 4G is the first wireless standard that truly supported high-speed internet browsing, with data speeds in the tens to hundreds of megabits per second per user, and international roaming capabilities in every handset.

5G will extend wireless connectivity into the range of gigabits per second, enabling fiber-optic speeds over wireless, which will support massive content transfers, driverless cars, new factory automation capabilities, live- stream television and media over our cellphones—and vast new applications not yet envisaged.

Prof. Rappaport led a video tour at the Brooklyn 5G Summit, which NYU Wireless hosted. Click on the image to watch (Video courtesy of IEEE.TV)

Where does NYU Tandon fit in the world of wireless R&D?

NYU Wireless is a global thought leader and research center of excellence, and is supported by the U.S. government and more than a dozen major wireless companies. I was recruited from the University of Texas in 2012, well before the merger between Brooklyn Poly and NYU was certain. My task was to build a center of excellence in wireless communications, since I had done it before in my career at Virginia Tech and the University of Texas. The administrations of Brooklyn Poly and NYU were extremely supportive, and our growth and rise to international prominence was faster than I could have ever imagined.

Our pioneering measurements and theoretical analysis in 2012, which proved to the world that millimeter waves (mmWave) could be used for mobile communications, certainly helped propelled our center to international prominence. Companies around the world were skeptical at first, but when they came to NYU Wireless, they eventually came to believe—and proved to themselves—that we can use spectrum never thought to be useful for mobile communications.

What’s the level of interest among students in wireless technology?

Students today are gravitating more towards machine learning and artificial intelligence, where computers are programmed to make decisions and process huge amounts of data. However, there are still many students excited by wireless, compelled by the magic of wireless.

How will advanced wireless change our urban lives?

Our lives will be greatly enhanced, as new applications and access to information will be faster than ever. Imagine having the speed of the internet connected to your pocket phone. New sensing and monitoring around the city can be used for improvement in safety, efficiency, and economy.

Are there major infrastructure projects necessary to upgrade to 5G?

Yes, as we increase the data rates provided over cellular networks, we must move the towers [that hold the antennas and equipment] closer to where the users are. This means shrinking the height of tall cell towers, and installing more “small cells” that allow for lightweight, low-power stations on lamp posts and small poles. We also will see the creation of low cost “phased arrays” or “adaptive antennas.” These are antennas that will be in our cell phones that automatically steer the signal to wherever the best tower is located, without us knowing it. This will also keep the energy from transmitting to our face.

What will the Keysight Technologies grant be going towards?

The Keysight gift is huge for our wireless center. It gives us the equipment needed to explore the next range of frequencies likely to someday be used for wireless networks, say in a decade from now. Our center is moving beyond mmWave, up to terahertz (THz) frequencies, where there is very little knowledge. Our new equipment will let us measure to frequencies above 100 GHz. With bandwidths of many GHz, this is so much greater than what most programs are able to do. These tools will let us build and test new systems, and will enable us to test and confirm new theories and principles that can benefit the wireless communications industry, as well as illuminate new concepts in imaging and sensing.

What are some examples of applications that would use these technologies?

Optical cables are the backbone to global internet communications. As we move to THz, the bandwidths become so great that wireless links could actually approach the data rates of optical cables. This has great promise for providing super high speed communications in rural areas, to cure the digital divide, as well as creating new architectures for cellphone and computer networks. We could even see wireless replacing wiring harnesses in vehicles, and on circuit boards. For medical imaging, there is some compelling evidence that THz could be safer than X-rays or CT scans for detecting problems in the body.

Brooklyn’s Recycling Startups Aim to Shrink the Trash Pile

The old-school approach to recycling was to ship the discarded material to distant processing plants, typically overseas. But that system suffered major disrupton last year, largely because China, as part of an anti-pollution crackdown, decided to stop importing most paper and plastic recyclables. That presented an epic question: Where to process all this stuff?

The answer lies close to home, judging by several Brooklyn startup companies that have pioneered ways to recycle everything from fabric to computers. “The waste industry is starting to come into a closed loop,” says Marisa Adler, a consultant at Resource Recycling Systems, who believes that in the next few years the industry will evolve on a local level.

“We’re really starting to realize that it’s all connected—through supply chains, through our limited natural resources—and I think that we’re going to start seeing more systems where the materials are recovered and the emerging technologies and startups are finding ways to more efficiently integrate recovered materials and resources back into products.”

These local entrepreneurs may help New York City achieve its Zero Waste goal, which calls for the end of sending waste to landfills by 2030. While the city’s sanitation department (DSNY) already collects 1,760 tons of recyclables each day, that’s still outweighed by a daily haul of 10,500 tons of residential and institutional garbage, shipped through facilities like the new Southwest Brooklyn Marine Transfer Station.

Among the Brooklyn startups aiming to make a dent in that trash pipline:

Handling spent brewers’ grain at Kings County Brewers Collective (Photo courtesy of Rise Products)

Turning Brewing Waste into Flour

Started by a group of five graduates from New York University, Rise Products creates high-fiber and protein-rich flour using spent grain from the beer-brewing process, usually malted barley. Co-founder Ashwin Gopi and his fellow graduates believe in a sustainability philosophy called industrial symbiosis, which promotes the idea of using one industry’s byproduct as the raw product of another.

The process is also called upcycling, meaning the creative re-use of material to make a better product or have a more desirable environment impact. In Rise’s case, the company says its “super flour” has 12 times the fiber and twice the protein of all-purpose flour.

Calling themselves “the Spent Grain People,” Rise Products upcycles leftovers from several of Brooklyn’s 20 craft breweries, including Greenpoint Beer & Ale Co. and Sixpoint Brewery. The leftover grain, which is turned into flour through a proprietary process, is used by bakers at Runner & Stone in Gowanus and other shops across New York City. “Chefs are looking for healthy, nutritious, and local ingredients,” Gopi says, “and I think we hit all of those points.”

Rise Products creates two main flours—light and dark—both of which can be bought on their website. They also create customized flours for the bakeries that order from them.

While the founders know their technology—CEO Bertha Jimenez has a PhD in technology management—they’re learning about sales and marketing on the job. “We’re not very good at selling our products,” Gopi admits. “It took us a while to even learn the vocabulary.” So the founders take a personal approach to sales, walking into local bakeries and striking up conversations with chefs about their flour to persuade them to test their products.

Rise Products is also currently conducting tests of the flour with Kellogg’s and Nestlé. The two food giants “are looking for upcycled ingredients, especially fiber, which is missing from the American diet,” Gopi says.

Bolts of castoff fabric can be sold by the yard; students can buy at a discount

A Solution for Textile Scraps

FABSCRAP collects unused rolls of fabric, clothing with imperfections, and leftover fabric from garment makers that can be reused by artists, crafters and students. Working out of the Brooklyn Army Terminal, which is situated near many clothing manufacturers, FABSCRAP also recycles material to create such products as carpet padding and moving blankets.

“Everyone at Brooklyn Army Terminal and the surrounding neighborhood have been so supportive about what we’re doing,” says Jessica Schreiber, founder of the startup. Her experience while working on the city’s clothing-recycling program at the DSNY inspired her to start FABSCRAP. While the city’s clothing-recycling program accepted castoff garments from consumers, it wasn’t equipped to receive commercial textile waste from businesses that were interested in participating.

FABSCRAP solved this problem by creating a process designed for processing raw textiles from fashion companies. Since its inception, FABSCRAP has collected more than 130,000 lbs. of raw material from dozens of fashion brands.

Co-founder Camille Tagle, a fashion designer by training, helps to classify and sell the fabric. Full rolls of fabric are cut into yards to be sold, while smaller pieces of textile are offered for sale as is. Students can buy fabric at a discount, while non-profit organizations can acquire fabric free of charge.

The company welcomes volunteers to help sort the fabric. After a three-hour shift, they’re welcome to help themselves to 5 lbs. of fabric. Says Schreiber: “Brooklynites tend to get the need for sustainability.”

O’Brien’s company has helped tame a “notoriously wasteful” industry (Photo courtesy of Earth Angel)

Helping Film Crews to Tread Lightly

The TV-and-film crews on Brooklyn’s streets not only take up a lot of parking spaces, they use a lot of energy and throw away plenty of trash. Greenpoint-based Earth Angel provides environmental consulting services for entertainment productions to help reduce their environmental impact.

Founded by Emellie O’Brien, who has a BFA in film and TV from NYU, Earth Angel has advised more than two dozen productions including Madam Secretary (CBS), The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (Amazon Studios), The Post (21st Century Fox), and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (Sony).

Entertainment production is “notoriously wasteful,” says the company, with examples ranging from fuel-guzzling generators to the dumping of used film sets into landfills. To date, the company says it has diverted 3,130 tons of waste from landfills and avoided the use of more than 1.5 million single-use plastic bottles.

Worthy causes benefit as well: Earth Angel has donated more than 59,000 meals and about 90 tons of unused products. What’s more, the firm says its efforts have successfully prevented 6,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases from entering the atmosphere.

Revivn distributed pre-owned tablet devices to young people at a neighborhood festival (Photo courtesy of Revivn)

Giving Electronics a Second Life

The nature of electronic hardware is that users are constantly upgrading. But what happens to the cast-offs? Many companies recycle by removing parts and precious metals, while dumping the rest in landfills. Revivn, a company based in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, has a more thoughtful approach.

Revivn serves businesses by collecting their excess hardware, making sure the data is secure, and repurposes the hardware based on whether it still has some usefulness left in it. The company partners with non-profit organizations including JustFix.nyc, Chicago Youth Centers and the Women’s Prison Association to place the hardware with disadvantaged people who might welcome a working computer, phone, keyboard or other device. Hardware items that technicians at Revivn deem unsalvageable are recycled responsibly using e-Stewards safety protocols.

Revivn aims to make the hardware-recycling process easy for businesses with a concierge service and deployment team that handles pickup and packaging of hardware. Companies that have recycled hardware through Revivn include Buzzfeed, Lyft, Teach for America, Christie’s and Twitter. Founded in 2012, the company has expanded to more than a dozen other cities and has plans to go global.

Hector Batista Named as New CEO of the Brooklyn Chamber

The Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce announced today that it has chosen a new president and CEO: Hector Batista, most recently the CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of New York City and a veteran of city government. Batista becomes the first Hispanic to serve as president in the group’s 100-year history.

“This is kind of a homecoming for me. I’m a local kid from Brooklyn, who went to high school in Brooklyn and continues to have roots in Brooklyn,” said Batista in the press release announcing his appointment. He succeeds Andrew Hoan, who left in May to become head of the Portland Business Alliance. The chamber is the largest such group in New York State, with more than 2,100 members, and was recognized as the state’s chamber-of-the-year in 2017.

Batista will join the chamber on Oct. 22 and will be officially welcomed aboard two days later at the group’s 2018 annual membership meeting at Gargiulo’s Restaurant in Coney Island. “I am truly thrilled to hand over the reins to a person who has made quite an impact in the non-profit sector and who has the experience and energy to lead this organization,” said Rick Russo, a senior vice president of the chamber who has served as acting president since Hoan’s departure.

A graduate of Brooklyn’s St. Francis College with a degree in political science, Batista began his career in economic-development roles, including service as a senior policy advisor to the Brooklyn borough president. In a city-wide post, he was the chief operating officer of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development. In the private sector, he ran external relations for Jeffrey M. Brown Associates, a construction-management firm. In the non-profit realm, he served as executive vice president of the American Cancer Society and CEO of the Vocational Foundation, which helps disadvantaged young adults.

In his eight years at Big Brothers Big Sisters, Batista expanded the group’s programs and fundraising, as well as doubling the number of youths served, to more than 5,200 annually across the five boroughs. He grew the organization’s on-the-ground footprint too, opening new offices in Staten Island, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx.

“We are excited to bring Hector on board as he really has the experience and enthusiasm needed to move the chamber forward with its programming and economic-development initiatives,” said Ana Oliveira, the chamber’s co-chair, in making the announcement. “The addition of Hector’s leadership also adds the element of diversity which is reflective of the borough, and really pushes the chamber into the next century.”

Video: in April, Batista spoke at the annual Sidewalks of New York gala, a signature event for Big Brothers Big Sisters of New York City (Video via YouTube)

Pilotworks Suddenly Closes, Leaving Cooks With No Kitchen

Pilotworks, the Brooklyn-based business incubator that helped launch hundreds of food-company startups, abruptly announced its closing on Saturday, leaving some 175 entrepreneurs suddenly without a home base. The move came “after failing to raise the necessary capital to continue operations,” the company said in a note on its website. “We realize the shock of this news and the disruption it causes for the independent food community …”

Indeed, the shutdown set off a scramble among dozens of food entrepreneurs to find new kitchens and other facilities at the start of their busiest season of the year. Said one of the displaced companies, cookie-maker Keto-Snaps, on its website: “We were shocked yesterday, not 2 hours after a wonderfully successful bake, to learn that Pilotworks Brooklyn, our commercial kitchen space, is suddenly, immediately, and without warning, closing all operations. Keto-Snaps … have been given three days to collect our things from the facility with no wind-down period and no support offered to find alternative space.”

Added Keto-Snaps co-founder Andy Barbera in a comment on The Spoon: “It’s unconscionable to end things so abruptly.” How abruptly? One source told The Bridge that suddenly the gas was cut off while the company was still in the middle of a production batch.

Malai Ice Cream was one of the many Pilotworks startups that went on to success (Photo by Heather Duval)

Reached for comment, a Pilotworks spokesman referred to a statement that the company had announced “that it will cease operations of all its kitchen spaces effective immediately” and that “all staff and members have been notified about the closure and are working with member companies to resolve pressing issues as quickly as possible.”

The incubator and commercial kitchen launched in 2016 as Brooklyn FoodWorks with a $1.3 million grant from the Brooklyn borough president’s office, with a particular focus on helping startups owned by women and minorities. The for-profit venture set up shop in a former Pfizer pharmaceutical plant at 630 Flushing Ave., on the northern edge of Bedford-Stuyvesant.

The incubator underwent a change of management after its original parent company folded and FoodWorks was acquired by entrepreneurs Nick Devane and Mike Dee. The duo changed the company’s name to Pilotworks and its business strategy to one of expanding across the U.S. Scaling up rapidly, the company established outposts in Newark, Dallas, Chicago, Providence and Portland, Ore.

Nick Devane was the company’s co-founder and the CEO until he stepped down in June

With a growth-oriented business plan, the company became a funding magnet, drawing $15.2 million from venture capitalists, according to Crunchbase, including $13 million just last December. Among the investors were celebrities of the food world, notably David Barber, co-owner of Blue Hill and Blue Hill at Stone Barns. “Food’s future depends on strong networks of like-minded eaters and lower barriers of entry for the entrepreneur. Pilotworks accomplishes both under one roof,” said Barber in a press release announcing last December’s funding.

The idea was delicious, drawing rapt attention from the likes of Food & Wine: “Pilotworks’ vision of entrepreneurship is all about taking people’s deep, passionate, personal connections to food, and lowering the barriers to entry that could otherwise prevent them from making that passion into a viable business to be shared. And in doing so, Pilotworks is helping to democratize food entrepreneurship.”

But hints of strains in the execution of that vision surfaced this summer, when co-founder Devane stepped down as CEO to transition to “a new role focusing on long-term creative and strategic initiatives.” Devane was succeeded as CEO by the company’s chief operating officer, Zach Ware, a veteran of the Republic of Tea and Zappos, who had joined Pilotworks four months earlier.

A Pilotworks member on the job at one of the incubator’s 16 workstations

Between its launch and its bitter end, the incubator fostered the launch of more than 300 new products. Among them: Zesty Z, started by the mother-son duo Lorraine and Alexander Harik, who produce a brand of Mediterranean condiment za’atar now available in Whole Foods and other stores around the U.S. Malai Ice Cream, the creation of entrepreneur Pooja Bavishi, has landed its spiced flavors on “best ice cream” lists and recently launched its own shop on Smith Street.

But now the sweet smell of success has turned sour as the incubator’s members search for explanations. “Instead of using the $13 million to make sure they were operating properly in their existing locations, they decided to expand,” David Roa of Superlost, a CBD-focused company, told Grub Street. “It was careless and irresponsible for them to do that considering hundreds of businesses depend on their facilities for their livelihoods.”

Update: In response to the closure, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and City Council Member Robert Cornegy, whose district includes the Pilotworks site, issued a joint statement: “Our community was disappointed to learn of the shuttering of Pilotworks. While we all understand the challenges and variability of the business world, it is concerning to see the impact on so many local food entrepreneurs who were tenants of this incubator. We thank non-profit organizations like Evergreen Exchange who are stepping up amid the confusion and triaging resources to facilitate work and storage spaces for more than 175 affected small businesses. It is our hope that NYCEDC, who has overseen this project since its initial inception, will work to find another shared commercial kitchen operator to operate this incubator for the affected food manufacturers who have relied on this space for their businesses’ well-being.”

Runners Defy a Rainstorm to Launch a New Brooklyn 5K

Just minutes before start time, sheets of rain were lashing Brooklyn, with flash-flood warnings posted. But the organizers were determined to carry on with the first-ever Brooklyn Runs, a corporate-challenge 5K organized by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce.

The weather cooperated. Showers turned into a light spritz. When the starter’s horn went off at 5 p.m. on Thursday, 143 runners took off on a course around Prospect Park, some as part of company teams with matching T-shirts, others as individuals out for a bit of adventure on a week night.

Members of the team from Downtown Music/Songtrust, including the women’s winner, Ashley Hofferber, front row left, with colleague Chinua Green

First across the finish line was Dawud Abdur-Rashid of Canarsie, a pre-med student, with a time of 19:05.33. He did not seem particularly taxed, turning around after the finish and running the loop in reverse as a cool-down exercise. “I enjoyed the rain as much as I could. I prefer rain over heat,” said Abdur-Rashid, who recently graduated from Manhattan College, where he ran on the cross-country and track-and-field teams.

The women’s winner was Brooklyn resident Ashley Hofferber, with a time of 24:16.71, who had just run the Chicago Marathon four days earlier. “Time-wise, it doesn’t take as long, but I’m tired,” she said. “I had a good pacer,” she added, pointing to her colleague, Chinua Green.

Dawud Abdur-Rashid of Canarsie was the winner among male runners

Hofferber and Green were on a team of 14 co-workers from Downtown Music Publishing/Songtrust, based in Manhattan, who said they do a lot of team-building exercises. “Next week we’re doing yoga,” said Green. “Last month, we went to the Color Factory. We’ve had a softball team and a kickball team.” Two of their colleagues, Asia Smulders and Gab Roth, placed 2nd and 3rd among women competitors. (More results and photos will be available at the Brooklyn Runs website.)

Running just after a downpour, the competitors had the loop road all to themselves

Samara Karasyk, EVP and chief of staff for the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, was a colorful presence at the finish line, cheering the runners as they crossed

Some competitors ran with bravado…

…while others expressed joy that their rainy slog was complete

After the race, the runners repaired to the LeFrak Center at Lakeside Prospect Park for an after-party. The Prospect Park Alliance was a partner in the event, while the principal sponsor was Just Energy, an alternative supplier of electricity and natural gas. Other sponsors of the run included Investors Bank, HSBC, National Grid, Mount Sinai Health System, and Con Edison. The Bridge was a media partner.