The Plan for 80 Flatbush Hits a Bump. What Happens Next?

After the community board votes no, Borough President Adams will consider "the new character of the community"

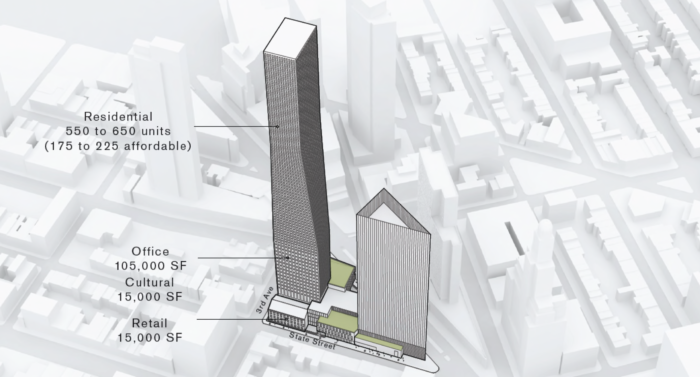

A diagram from the presentation of the 80 Flatbush proposal by the Educational Construction Fund

This outcome wasn’t a surprise. Brooklyn Community Board 2 voted overwhelmingly last night to oppose the proposed rezoning of the 80 Flatbush development site, which would allow for a near tripling of the density on the block bordered by Flatbush and Third avenues and State and Schermerhorn streets. The rezoning would allow the construction of two towers, rising 560 and 986 feet, while delivering affordable housing, cultural space, a new elementary school, and a replacement high school, thanks to the value of hundreds of market-rate apartments.

At the meeting, which took place in a Long Island University lecture hall, the only CB 2 member to comment, Boerum Hill resident Dwight Smith, tried to reframe the debate. “We’re not anti-development, quite the contrary,” he said, turning to the audience and reporters. The Boerum Hill Association, he said, supports transitional zoning, as designated by its location in the Special Downtown Brooklyn District, not the commercial core of Downtown Brooklyn.

“Forty stories is not anti-development,” he said, referring to the single tower along Flatbush that could be built as-of-right, with no rezoning. “What we strongly oppose,” he said, is “a grossly excessive development.” The board then rejected the rezoning by a vote of 32-1 (with five abstentions and two recusals), unwilling to offer conditional approval for a project they considered unable to be tweaked. (Here’s the one supporter’s take.)

Looking east along Schermerhorn Street, where the taller 80 Flatbush tower at the end on the south (right) side, would be more than 50% taller than the highest building on the left, The Hub (Photo by Norman Oder)

What Happens Next?

But such votes are only advisory, and the as-of-right alternative brings none of the promised benefits, which help address the shortcomings of the 2004 Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, aimed to create office space, but which instead brought a wave of market-rate housing and no new schools for those residents.

So it’s unclear how much the vote will influence Borough President Eric Adams, whose recommendation is also advisory but represents a broader constituency, and Council Member Stephen Levin (District 33), who holds the key voice on the City Council. So far, he has been wary of taking sides, though he has acknowledged to The Bridge that the project might be seeking to accomplish too much.

The other big question is how much compromise is possible. 80 Flatbush has been presented as a package—density delivers benefit—but without clarity about the value of the increased bulk to Alloy Development, the Dumbo-based firm developing the site, and the terms of the company’s deal with the New York City Educational Construction Fund, which partners with developers on projects that contain schools.

“We appreciate that the Community Board took the time to review our application,” said Alloy President AJ Pires in a statement after this week’s vote. “While we respect its position, we’ve also received a lot of support for the project, both in the neighborhood and citywide. The consensus among those many supporters is that building in Downtown Brooklyn along Flatbush Avenue and across from one of the largest transit hubs in the City to deliver affordable housing, two schools and cultural space makes 80 Flatbush a model for intelligent development.”

Community Board 2 member Dwight Smith speaking at this week’s meeting; Alloy Development President AJ Pires is in the checked shirt at center (Photo by Norman Oder)

If the history of contested developments is any guideline, such statements typically obscure some wiggle room. It’s hard to believe that Alloy hasn’t sketched out alternatives, and that Levin hasn’t tried exploring other ways to deliver a new facility for the Khalil Gibran International Academy, which currently occupies antiquated buildings onsite, and a new elementary school.

Sussing out the Borough President

Adams must offer his recommendation before the project proceeds to a vote by the City Planning Commission and then the City Council. “I’d like to believe he’s concerned about the tripling of the FAR [Floor Area Ratio, a measure of development rights] being a bad precedent for Brooklyn or anywhere,” said Howard Kolins, president of the Boerum Hill Association, speaking after the CB 2 meeting.

As it happens, Adams sounds concerned–somewhat. Though he didn’t offer substantive comments during his brief appearance at the public hearing his office held on April 30, the borough president brought up 80 Flatbush during an interview shortly afterward with the Max & Murphy podcast from Gotham Gazette and City Limits.

“We look at each location individually, and we assess: Is it going to fit into the new character of the community?,” Adams said. “Because we can’t merely say it’s going to fit into the old character, because the character has changed. Brooklyn has changed. We would not have believed the skyline of Downtown Brooklyn would have been what we are looking at now.”

The character, indeed, has changed, with new towers rising along Flatbush and an Apple Store and Whole Foods across the street in the 300 Ashland tower, which contains 20% low-income affordable units and was designed to avoid obscuring views of the iconic clock on the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, now the One Hanson residential building.

The proposed towers at 80 Flatbush are shown just to the left of the supertall skyscraper planned for 9 Dekalb Ave. (Rendering courtesy of Alloy Development)

“And so the real challenge,” Adams continued, regards projects “on the barriers of those small, low-zone communities, such as a very challenging application, 80 Flatbush Avenue. It neighbors a block where we have a small, tree-lined block where you have those brownstones. So we have to think that through and figure out, How do we do it without overwhelming the existing communities that are there?”

“So our goal is to really speak with the Council person on the ground, find out what are their thoughts,” he said. “How do we do a perfect combination between creating more affordable housing–that’s the No. 1 issue that we are hearing about in this borough … but at the same time take into account the existing history of the community?”

If affordable housing is Adams’ priority, then the housing equation of 80 Flatbush might change. The 200 permanently affordable low-income units (of 922 total apartments) are not due until 2025, when the larger, second building is planned for completion–and deadlines often slip in construction. One might imagine a proposal to front-load some of the affordable units.

One of the arguments in favor of the project is that it would provide new space for two schools (Rendering courtesy of Alloy Development)

But a “perfect combination” may be elusive. Consider: Alloy’s partner on the affordable housing aspect of the project is the respected Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC), led Michelle de la Uz, who as a member of the City Planning Commission has been the most critical of Mayor de Blasio’s rezonings, saying they do too little for the poor. The calculation that this deal is worth it contrasts with the FAC’s posture during the Atlantic Yards debate, when the group was more critical of the developer’s proposal.

Adversaries Dig in

If the initial public hearing, sponsored by the Community Board, drew mainly project opponents from nearby neighborhoods, the hearing sponsored by the Borough President’s office featured a broader mix of commentary.

Those expressing support included people connected to the project—the Khalil Gibran school, unions, nonprofits—as well as representatives of pro-business organizations like the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce and the Real Estate Board of New York. And while Alloy has spent considerable sums on lobbying (more than $400,000) and public relations, it also gained the perhaps unexpected support of a newly vocal YIMBY (Yes in My Back Yard) contingent in favor of more development to provide housing and other benefits.

Several representatives of Open New York (a reported 30 active members) made the not unreasonable argument that New York City needs more housing, that sites near transit can best absorb it, and that wealthier communities should accept their fair share, partly to reduce the pressure of gentrification deeper in Brooklyn. Then again, their scornful posture toward project opponents was not matched by any skepticism toward the project and the deal itself.

The buildings along State Street opposite the site are generally low-rise townhouses (Photo from Draft EIS)

(How fast the addition of market-rate housing can ease the housing crunch remains in question. New School Professor Rachel Meltzer told Politico that, because housing markets are segmented, “building a lot of luxury units is not going to help those on the lower end of the affordability spectrum, and if it does, it’s going to take a really long time to trickle down.”)

Proponents and opponents see 80 Flatbush through competing lenses, neither without distortions. If the 80 Flatbush site is to be considered “Downtown Brooklyn,” that tends to dismiss the history of transitional zoning, in which building heights step up gradually from Schermerhorn Street. And if organizations like Transportation Alternatives say they voice “support solely for the proposal to remove parking minimums” at the site, thus potentially reducing auto traffic, why are they presented as supporting the project as a whole?

Then again, those decrying “No Towers Over Boerum Hill” actually accept the as-of-right tower that Community Board member Smith mentioned. If opponents ask, not unreasonably, why the city can’t use tax dollars to build schools rather than make development deals, that provokes a more systemic question: how many condo owners are willing to sacrifice their 421-a tax break and how many home owners support property tax reform that might cause pain?

A Tight Fit

If building big near a subway hub generally makes sense, can two towers and two schools, with housing and office space, work on this 1.4-acre site? Even if parking is banned, can deliveries really be managed, as the environmental review claims? One lesson of the Barclays Center is that a tight fit leaves little margin of error to accommodate delivery vehicles on narrow streets.

The project would contain a mix of buildings, old and new, as well as a mix of uses (Drawing courtesy of Alloy Development)

Even before 80 Flatbush was proposed, some thought the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning left things out of balance. During an April 2015 panel at Brooklyn Historical Society examining the rezoning a decade later, City Tech’s Kevin Hom, an architect, observed, “As an academic and as a planner, I sort of scratch my head” at the “anomaly that has been created by [the Department of] City Planning,” in which there’s little adjustment between low-rise and high-rise residential districts, throwing the “balance out of the normal ascension of density.” Actually, there is an ascension of density moving from the south, one poised to be vastly remade by 80 Flatbush.

The rezoning-approval process is a “gun to your head,” said Boerum Hill’s Kolins, criticizing the take-it-or-leave-it proposal. “We need schools, we need affordable housing, we’re so in favor of Khalil Gibran getting a new high school. Can we get it back to a place where we the community has some real input?” In this case, that might be up to Alloy–or the few elected officials with clout.