Will Brooklyn’s Freight Trains Get Rolling Again?

The city's plan to reduce truck traffic could bring the little-used Bay Ridge line rumbling back to life

A locomotive rolls by on the New York & Atlantic tracks in Queens (Photos by Chris Polansky)

On occasional moments of quiet in Brooklyn, when the sounds of honking horns and garbage trucks die down, residents can hear the lonely whistle of a freight train. Many might wonder where it’s coming from, since lines of boxcars are not a familiar sight in Kings County.

The answer is that a few freight trains still roll along the Bay Ridge Branch of the New York & Atlantic Railway, typically carrying goods bound for points east. The 12-mile stretch of track snakes across the borough from the harbor just south of the Brooklyn Army Terminal, through the low-rise blocks of Borough Park, past Brooklyn College’s stately campus, and through industrial zones in Flatlands, Canarsie and East New York, before terminating at a yard in Glendale, Queens.

For much of its length, the Bay Ridge line is hidden behind overgrowth and fencing. With the exception of once or twice a day when a train rattles by, the line gives neighbors and passersby no indication that it’s alive.

It wasn’t always like this. In its heyday from the beginning of the 20th century through the mid 1960s, freight and passenger trains shared the tracks, carrying commuters and commodities, reportedly at a rate of up to 30,000 cars a year. That’s ten times the line’s current average of 3,000 freight-only railcars per year, according to James Bonner, the New York & Atlantic Railway’s president.

“As manufacturing in New York City and on Long Island declined, and better roads and interstate access materialized, volume declined significantly,” Bonner said, as the economy shifted to a reliance on trucks for the movement of goods. Today, about 90% of all freight going in or out of New York City is carried by tractor-trailer trucks, which contributes to congestion, damage to infrastructure, and environmental harm.

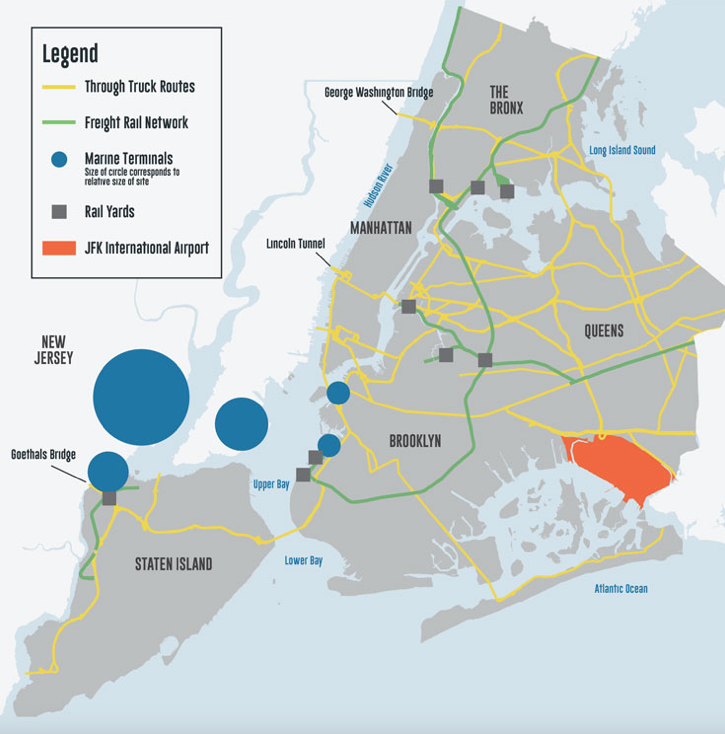

But now freight-rail advocates see a golden opportunity for growth along the Bay Ridge line, thanks to a city’s Freight NYC initiative, a $100 million plan to modernize the city’s freight-distribution system. The plan, from the city’s Economic Development Corp. (NYC EDC), aims to rejigger the region’s transportation infrastructure to spur greater use of boats and trains in the shipment of the 400 million tons of freight that flow in and out of the city each year.

Improvements to the rail network, the plan postulates, will grow the economy and foster job growth by lowering operating costs for industrial businesses, and in turn encouraging new businesses to move here. “New York’s supply chain is at a crossroads,” states Andrew Genn, senior vice president of the Ports & Transportation Dept. of the NYC EDC. “This critical infrastructure, which served the city well in the past, is not equipped to handle the exponential population growth and increased consumer demand it has already begun to see.”

In Brooklyn and Queens, the plan calls for new facilities to smooth the shipment of material from one transport mode to another. “We expect to have up to five new facilities by 2020, which will include new platforms, track, shed space, scales, silos and other yard equipment to make it easier to transload to trucks for final-mile deliveries,” stated Genn.

The Bay Ridge branch joins busier New York & Atlantic branches in Glendale. Walking through a jungle of train tracks and boxcars in the yard, crushed stone crunching under his boots, railroad chief Bonner pointed to a train pulling into the yard from points west, and rattled off its cargo: steel, cooking oil, lumber, and produce.

“We handle about 30,000 carloads per year here,” said Bonner, counting the traffic on all of its branches, stretching from Long Island City to Montauk. “That’s the equivalent of 120,000 truckloads.” The freight line runs on tracks owned by the Long Island Rail Road. All told, the New York & Atlantic has 270 route miles, 13 locomotives, and about 60 employees.

The Freight NYC plan will be beneficial to the industrial and food-related businesses along the railroad’s corridor, proponents say. But not everyone is persuaded that the investment numbers add up. Skeptics include Bill Wilkins, director of economic development for the Local Development Corp. of East New York, which advocates for the area’s industrial businesses.

“In concept, it sounds like a great idea: reduce congestion, good for the environment,” said Wilkins. “I was of that same opinion. But we did a deep dive, and the economics don’t work. It’s no silver bullet.”

While some businesses with large properties and sizable lines of credit could benefit from the volume of goods carried by rail, Wilkins said, those make up a small fraction of the borough’s industrial sector. “The industrial parks with 300,000 sq. ft., the Amazons of the world who are flush with cash, maybe for them rail makes sense,” he said. “Our businesses are usually 10,000 to 20,000 sq. ft. They don’t need rail. And it’s New York City— God’s not making any more land.”

Wilkins recognizes the problem of over-reliance on trucking, but doesn’t think rail, at least in its traditional form, should be the linchpin of a solution. “Because of our increasing population, we are at capacity as far as our roadways go,” he said. “We really do need to look at alternative methods. But maybe it’s not the old Santa Fe lines and long cars. Maybe it’s smaller cars, smaller trailers, boats, barges. But ultimately, we still need to have our shelves full of goods.”

West from Wilkins’ turf on the Bay Ridge Branch, at the Brooklyn Terminal Market in Canarsie, a rail spur from the main track now sees its share of deliveries, but nothing like it used to be, according to Frank Seddio, the Democratic Party’s county leader and the market’s lawyer.

“We used to get watermelons, other things,” Seddio said. “They don’t use it as much as they used to.” Now the produce arriving by rail, according to Charlie Ciraolo, president of the market’s merchants association, consists of just potatoes and onions. “I wish the train would bring more,” he said, “like back in the day.”