Lessons of Rezoning: When It Doesn’t Work Out as Planned

A report on Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City says a smarter city review process might have staved off problems

A view of the Brooklyn and Manhattan skyline from the Hub, a residential rental tower that is currently Brooklyn's tallest building (Photo by Stefano Ukmar/The New York Times/Redux)

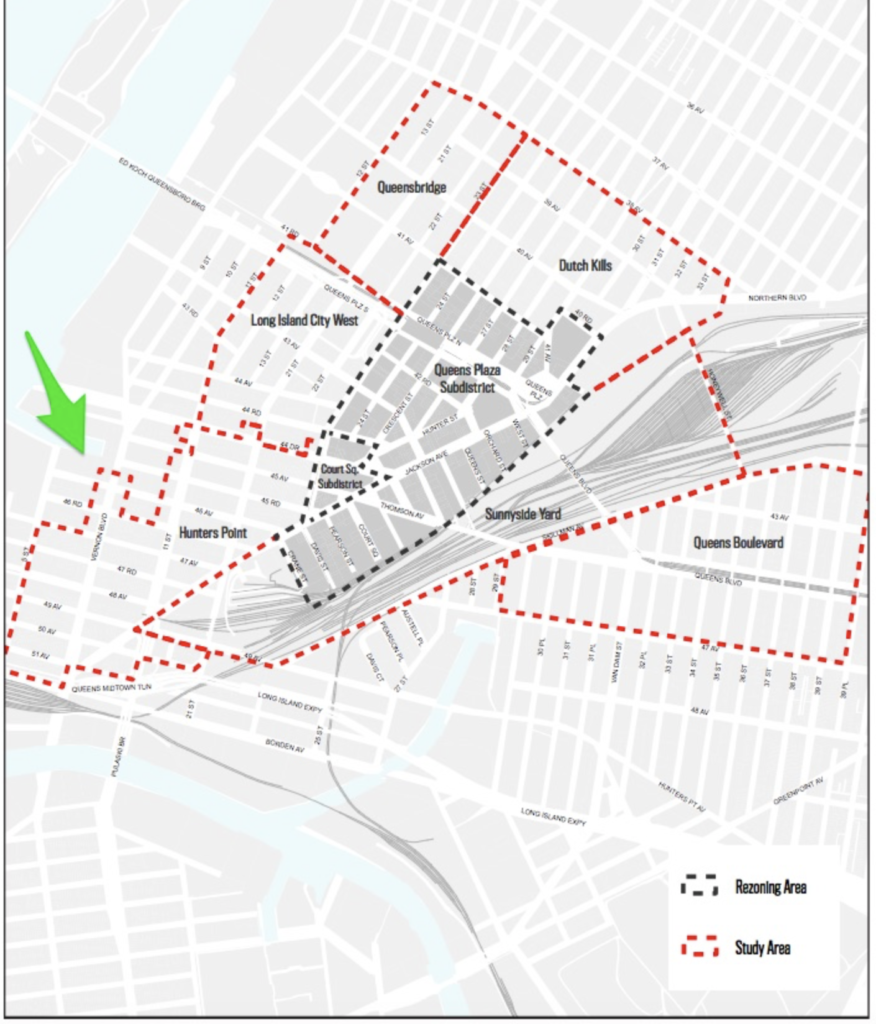

Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City (LIC) have been utterly transformed since city policy toward those neighborhoods changed in 2004 and 2001, respectively. Numerous towers have sprouted after rezonings unlocked permission to build big on formerly low-rise industrial or commercial space. By one account, LIC is the nation’s fastest-growing neighborhood.

But those new towers almost exclusively contain apartments, rather than the expected result of mainly office space. The failure to plan for new residents means overcrowded public schools and insufficient open space, according to a recent report from the Municipal Art Society (MAS), a longstanding advocate for a more livable city. The neighborhoods are “whiter, wealthier, and more crowded than ever.”

In Downtown Brooklyn, a key piece of open space, 1.15-acre Willoughby Square Park—to be built over a parking garage—didn’t materialize as planned. (In fact, if the long-delayed deal doesn’t close by Jan. 27, the developer will be in default, according to Brooklyn Paper.)

While the new supply may be good news for renters of those units, the rezonings failed to require that new market-rate apartments in a development should cross-subsidize affordable ones, which is city policy today. So that has sparked catch-up projects like 80 Flatbush, a spot rezoning recently approved with far greater bulk than permitted in 2004, under the rationale that only larger towers could make affordable units and new schools financially feasible.

What Went Wrong?

A smarter review process would help. The MAS report, A Tale of Two Rezonings, points to serious flaws in the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) process, which is supposed to mitigate adverse impacts. Better scenario planning and periodic monitoring could enhance future city rezonings, the report said, as well as the state process expected to approve Amazon’s creation of a new headquarters in LIC.

Yes, these neighborhoods, given their proximity to Manhattan and extensive subway service, were ripe for new density. The MAS report suggests the new burdens on transportation in Downtown Brooklyn were relatively modest, though average ridership in LIC’s three main subway stations increased sevenfold compared to the city-wide rate over the last six years.

“A series of deficiencies already exist in this community [LIC],” Elizabeth Goldstein, president of the MAS, told The Bridge. That means the Amazon review should consider not merely the waterfront corporate headquarters, she said, but “how that integrates in a thoughtful way into the community, and doesn’t exacerbate problems.”

In a November op-ed for the New York Times, Goldstein cited LIC’s deficits in schools and open space, and encouraged Amazon founder Jeff Bezos to “leverage” the attention on the Amazon deal to “demand long overdue relief” for neighborhood residents and to build a stronger city going forward.

How much of that will happen? At a contentious oversight hearing Dec. 12, City Council members pressed Amazon and city officials regarding such contributions, and were told it was a subject for further discussion. Council members also expressed dismay that the land-use changes involved in the Amazon development are being assessed by the state’s looser review process, rather the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).

Planning for Office Space Didn’t Work

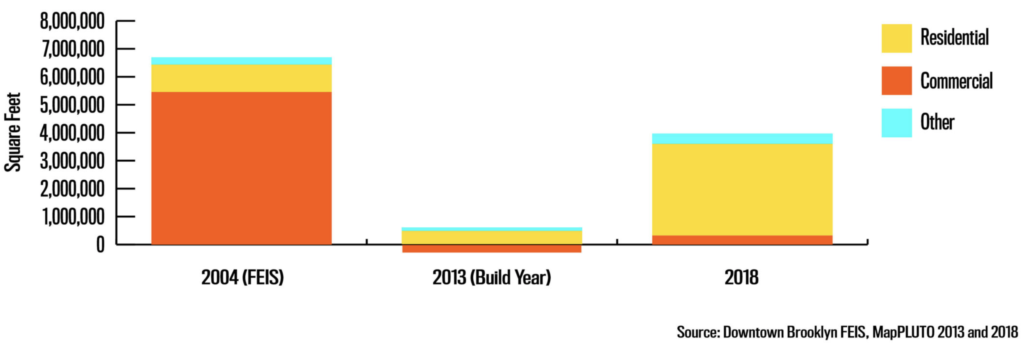

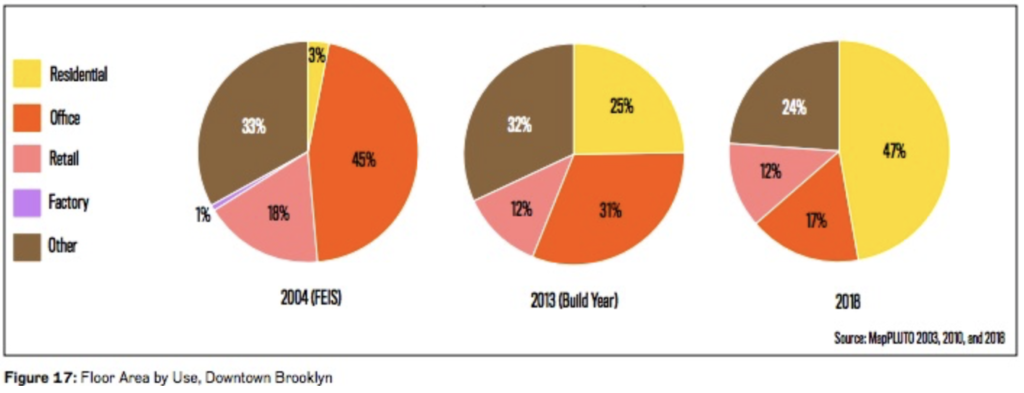

Recent history points out the perils of prediction. The Downtown Brooklyn Rezoning Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) projected that 6.5 million sq. ft. of development, mostly office space, would materialize by 2013 on the 33 blocks at issue, according to the MAS report. In fact, only a fraction emerged by that year, with more residential than office space, but since then many more apartment buildings have risen.

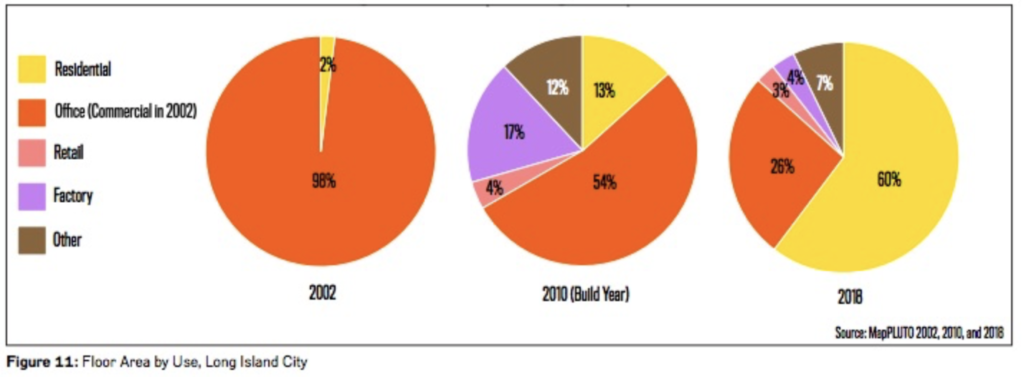

Similarly, though the Long Island City FEIS projected about 5.7 million sq. ft. of new development by 2010 on 39 blocks, mostly office and commercial space, the area actually lost commercial space because of demolitions. Instead came apartments.

What happened? Despite expert prognostication about the need for new back-office space for the financial industry, in order to prevent those companies from being lured to New Jersey, changes in the economy and technology upended such plans. Builders pivoted to the residential market.

That displaced small businesses in Downtown Brooklyn, as the Pratt Center for Community Development explained in a 2008 report. There was a partial upside. Had the commercial centers been built as planned, “you’d have another neighborhood that’s completely dead at night,” observed MAS Planning Committee Chair Jill Lerner at a Nov. 8 panel discussing the report.

Indeed, with so many new residents in Downtown Brooklyn, there’s finally a demand for nearby office jobs. (That said, developers of the recently proposed tower at 625 Fulton St., potentially rising 942 feet, are requesting a rezoning for unprecedented density to allow more large-floorplate office space. That implies that the 2004 rezoning now doesn’t work economically for office space, given current land costs.)

Still, Lerner said, “we missed the possibility of solving some of our displacement problems in other neighborhoods” by not requiring affordable housing in the original plan. Added fellow panelist Elena Conte, Director of Policy for the Pratt Center, “When we get it wrong, we’re not only making it bad for people in that neighborhood … it’s bad for the system.”

The Pratt Center recently issued its own report warning that the city’s standard method for predicting indirect residential displacement—the ripple effects of gentrification—vastly underestimates the number of people forced out because it assumes, for example that all people living in rent-stabilized buildings will be protected.

Planners Missed Developer Tactics

Hindsight shows several flaws in the city review process. As the MAS observes, that process requires estimation of a “Reasonable Worst Case Development Scenario” by a specific year. With both Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City, those scenarios were way, way off.

The planners didn’t anticipate savvy developer tactics that produced far taller and bulkier buildings than anticipated, thanks to so-called zoning lot mergers, which allow multiple parcels to be combined for bigger buildings. One result: the buildings cast far larger shadows on green space than ever studied in the review.

As the MAS report details, 32 completed or planned developments in Long Island City and 21 in Downtown Brooklyn have used transfers of development rights from those zoning lot mergers. Examples in Downtown Brooklyn are Avalon Fort Greene and the Hub (333 Schermerhorn St.), both far larger buildings than contemplated for those sites in the city’s review.

Going Forward, a Better Way?

In future city reviews, the MAS recommends that evaluators consider small lots to account for the possibility of lot mergers and much larger buildings. The projected “build year” should assess all development sites under a rezoning, rather than only those likely to be developed soon. (After all, many more buildings in LIC and Downtown Brooklyn emerged just after their respective “build years.”)

Also, the report suggests that planners analyze alternative possible development scenarios, such as one with residential rather than commercial space. For example, because the rezonings focused on office space, rather than thousands of new residents, the reviews failed to identify any the loss of open space for those residents. (One sign of progress: the Brooklyn Strand project, with a $10 million boost from the governor’s office, is gaining momentum.)

Another MAS idea: the “Optimal Sustainable Development Scenario,” which focuses on practices that reduce water and energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, urban heat-island effect, and more. That’s especially relevant in projects near the precarious waterfront.

To avoid deficits like the delayed Willoughby Square, the MAS suggests that mitigation commitments—the civic betterments required in the environmental review—should be tracked, and that an independent body of experts track projects impacts over time.

Another Solution: Look More Broadly

The two major rezonings analyzed in the MAS report were undertaken without due consideration of other land-use changes in the surrounding neighborhoods, the report points out. Not long after the city rezoned the central part of Long Island City, two other large sub-neighborhoods nearby were rezoned—but the three efforts were not evaluated together.

“Currently, the unmitigated impacts that result from rezonings are not considered when new actions are proposed in neighboring areas,” the report states. “This is especially problematic in Long Island City where countless impacts have yet to be addressed, and two new projects are under review: the Long Island City Innovation Center and the Anable Basin Rezoning.”

As of early November, the latter two proposed rezonings were being reviewed separately, thus calling into question whether the city would downplay their cumulative impacts. But those two projects, with one block subtracted, now translate into the site proposed for Amazon’s new headquarters. (The subtracted block will still be part of the state’s overall review, however, sparking criticism from City Council members, as Crain’s New York Business reported.)

So that’s an argument for the so-called Generic EIS: environmental reviews that assess broader impacts in a larger neighborhood. (Other city projections can be flawed too. Public-school advocates, in a recent op-ed in Gotham Gazette, observed that “the city has consistently underestimated the real need for public schools.”)

That said, the MAS didn’t pursue its report because it foresaw Amazon, but rather because the city regularly seeks land-use changes, such as to foster affordable housing. “We need to make sure if we’re doing this kind of environmental review, we do it in the best way possible,” Goldstein said. “Rezonings are happening all over the city.”

“The big takeaway from Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City,” she said, “is that the ‘purpose and need’ for which the city initiated these rezonings was not achieved.”

How to change the city’s approach? The process has begun, according to Goldstein, as MAS starts briefing city officials and council members. “We are very engaged in the City Council Charter reform process,” she said, referring to a council-spurred review that likely will produce new ballot measures next year. The new spotlight on Long Island City—perhaps even brighter now that, in Seattle, Amazon rival Microsoft has said it will devote $500 million to affordable housing—might further influence decision-makers.