Lessons of Rezoning: When It Doesn’t Work Out as Planned

Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City (LIC) have been utterly transformed since city policy toward those neighborhoods changed in 2004 and 2001, respectively. Numerous towers have sprouted after rezonings unlocked permission to build big on formerly low-rise industrial or commercial space. By one account, LIC is the nation’s fastest-growing neighborhood.

But those new towers almost exclusively contain apartments, rather than the expected result of mainly office space. The failure to plan for new residents means overcrowded public schools and insufficient open space, according to a recent report from the Municipal Art Society (MAS), a longstanding advocate for a more livable city. The neighborhoods are “whiter, wealthier, and more crowded than ever.”

In Downtown Brooklyn, a key piece of open space, 1.15-acre Willoughby Square Park—to be built over a parking garage—didn’t materialize as planned. (In fact, if the long-delayed deal doesn’t close by Jan. 27, the developer will be in default, according to Brooklyn Paper.)

While the new supply may be good news for renters of those units, the rezonings failed to require that new market-rate apartments in a development should cross-subsidize affordable ones, which is city policy today. So that has sparked catch-up projects like 80 Flatbush, a spot rezoning recently approved with far greater bulk than permitted in 2004, under the rationale that only larger towers could make affordable units and new schools financially feasible.

What Went Wrong?

A smarter review process would help. The MAS report, A Tale of Two Rezonings, points to serious flaws in the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) process, which is supposed to mitigate adverse impacts. Better scenario planning and periodic monitoring could enhance future city rezonings, the report said, as well as the state process expected to approve Amazon’s creation of a new headquarters in LIC.

Yes, these neighborhoods, given their proximity to Manhattan and extensive subway service, were ripe for new density. The MAS report suggests the new burdens on transportation in Downtown Brooklyn were relatively modest, though average ridership in LIC’s three main subway stations increased sevenfold compared to the city-wide rate over the last six years.

“A series of deficiencies already exist in this community [LIC],” Elizabeth Goldstein, president of the MAS, told The Bridge. That means the Amazon review should consider not merely the waterfront corporate headquarters, she said, but “how that integrates in a thoughtful way into the community, and doesn’t exacerbate problems.”

In a November op-ed for the New York Times, Goldstein cited LIC’s deficits in schools and open space, and encouraged Amazon founder Jeff Bezos to “leverage” the attention on the Amazon deal to “demand long overdue relief” for neighborhood residents and to build a stronger city going forward.

How much of that will happen? At a contentious oversight hearing Dec. 12, City Council members pressed Amazon and city officials regarding such contributions, and were told it was a subject for further discussion. Council members also expressed dismay that the land-use changes involved in the Amazon development are being assessed by the state’s looser review process, rather the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).

Planning for Office Space Didn’t Work

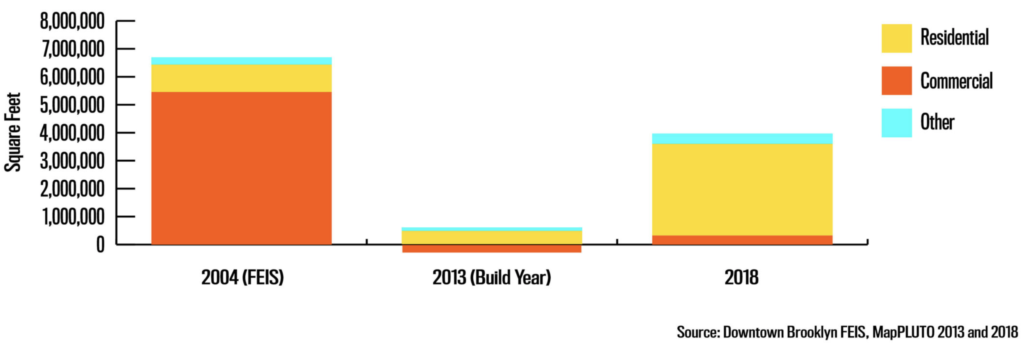

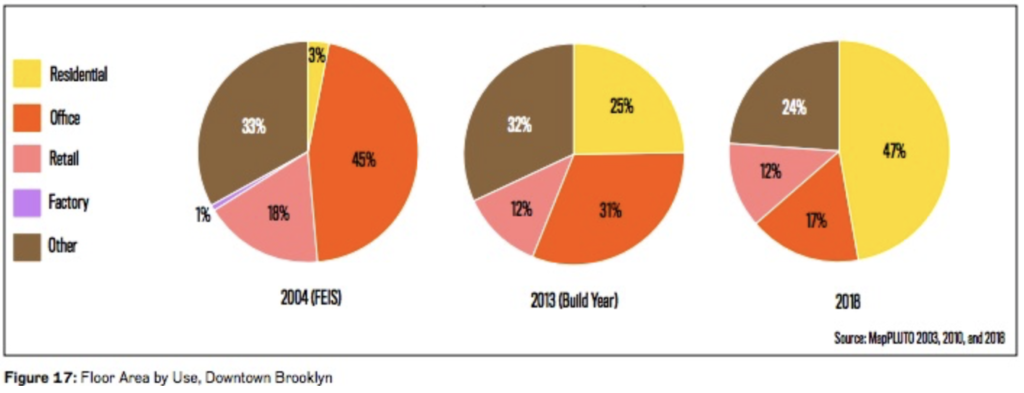

Recent history points out the perils of prediction. The Downtown Brooklyn Rezoning Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) projected that 6.5 million sq. ft. of development, mostly office space, would materialize by 2013 on the 33 blocks at issue, according to the MAS report. In fact, only a fraction emerged by that year, with more residential than office space, but since then many more apartment buildings have risen.

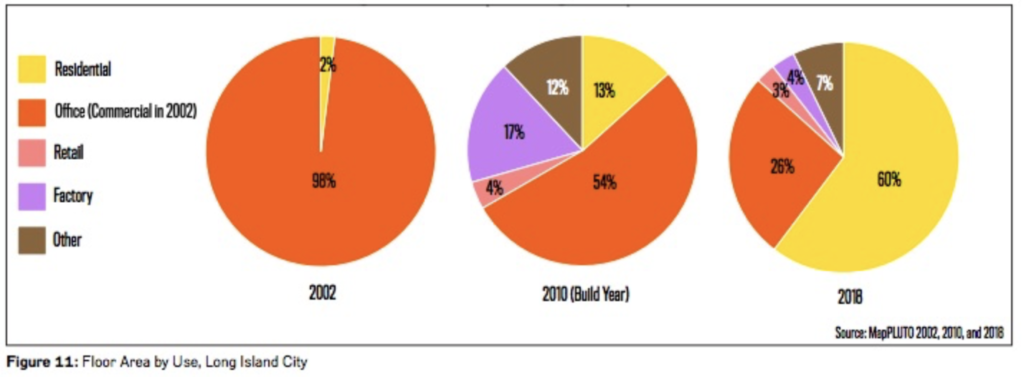

Similarly, though the Long Island City FEIS projected about 5.7 million sq. ft. of new development by 2010 on 39 blocks, mostly office and commercial space, the area actually lost commercial space because of demolitions. Instead came apartments.

What happened? Despite expert prognostication about the need for new back-office space for the financial industry, in order to prevent those companies from being lured to New Jersey, changes in the economy and technology upended such plans. Builders pivoted to the residential market.

That displaced small businesses in Downtown Brooklyn, as the Pratt Center for Community Development explained in a 2008 report. There was a partial upside. Had the commercial centers been built as planned, “you’d have another neighborhood that’s completely dead at night,” observed MAS Planning Committee Chair Jill Lerner at a Nov. 8 panel discussing the report.

Indeed, with so many new residents in Downtown Brooklyn, there’s finally a demand for nearby office jobs. (That said, developers of the recently proposed tower at 625 Fulton St., potentially rising 942 feet, are requesting a rezoning for unprecedented density to allow more large-floorplate office space. That implies that the 2004 rezoning now doesn’t work economically for office space, given current land costs.)

Still, Lerner said, “we missed the possibility of solving some of our displacement problems in other neighborhoods” by not requiring affordable housing in the original plan. Added fellow panelist Elena Conte, Director of Policy for the Pratt Center, “When we get it wrong, we’re not only making it bad for people in that neighborhood … it’s bad for the system.”

The Pratt Center recently issued its own report warning that the city’s standard method for predicting indirect residential displacement—the ripple effects of gentrification—vastly underestimates the number of people forced out because it assumes, for example that all people living in rent-stabilized buildings will be protected.

Planners Missed Developer Tactics

Hindsight shows several flaws in the city review process. As the MAS observes, that process requires estimation of a “Reasonable Worst Case Development Scenario” by a specific year. With both Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City, those scenarios were way, way off.

The planners didn’t anticipate savvy developer tactics that produced far taller and bulkier buildings than anticipated, thanks to so-called zoning lot mergers, which allow multiple parcels to be combined for bigger buildings. One result: the buildings cast far larger shadows on green space than ever studied in the review.

As the MAS report details, 32 completed or planned developments in Long Island City and 21 in Downtown Brooklyn have used transfers of development rights from those zoning lot mergers. Examples in Downtown Brooklyn are Avalon Fort Greene and the Hub (333 Schermerhorn St.), both far larger buildings than contemplated for those sites in the city’s review.

Going Forward, a Better Way?

In future city reviews, the MAS recommends that evaluators consider small lots to account for the possibility of lot mergers and much larger buildings. The projected “build year” should assess all development sites under a rezoning, rather than only those likely to be developed soon. (After all, many more buildings in LIC and Downtown Brooklyn emerged just after their respective “build years.”)

Also, the report suggests that planners analyze alternative possible development scenarios, such as one with residential rather than commercial space. For example, because the rezonings focused on office space, rather than thousands of new residents, the reviews failed to identify any the loss of open space for those residents. (One sign of progress: the Brooklyn Strand project, with a $10 million boost from the governor’s office, is gaining momentum.)

Another MAS idea: the “Optimal Sustainable Development Scenario,” which focuses on practices that reduce water and energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, urban heat-island effect, and more. That’s especially relevant in projects near the precarious waterfront.

To avoid deficits like the delayed Willoughby Square, the MAS suggests that mitigation commitments—the civic betterments required in the environmental review—should be tracked, and that an independent body of experts track projects impacts over time.

Another Solution: Look More Broadly

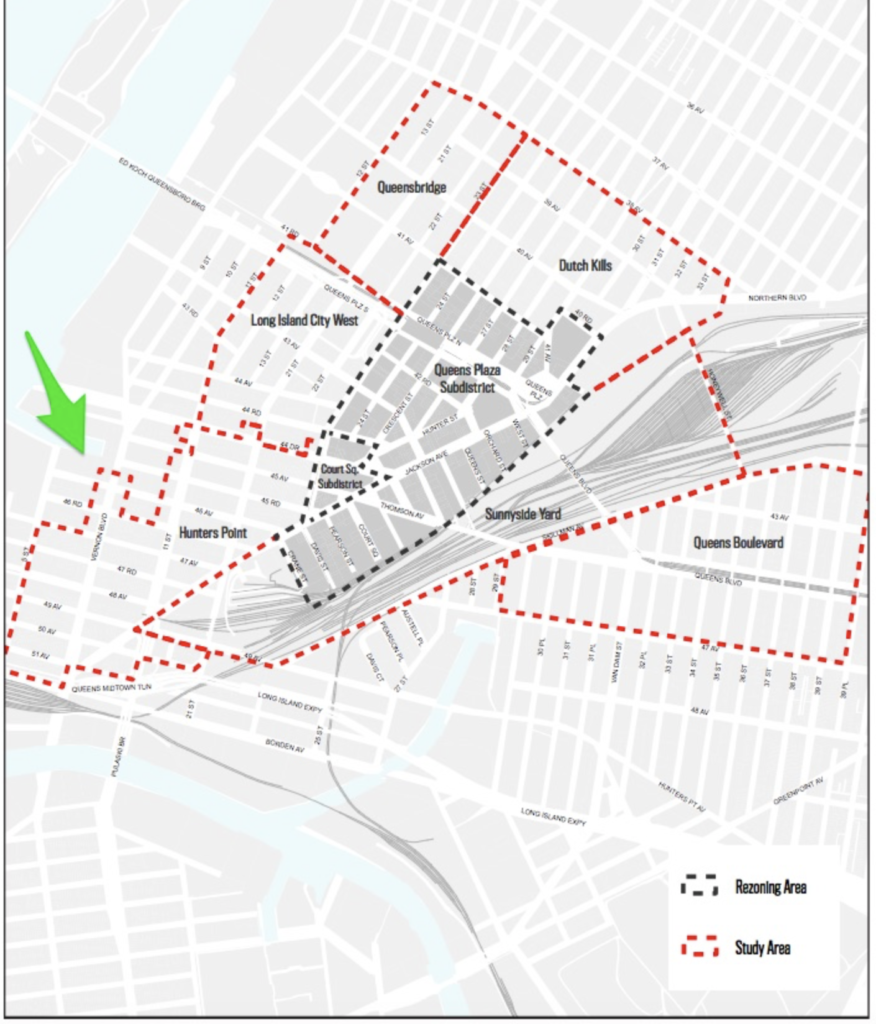

The two major rezonings analyzed in the MAS report were undertaken without due consideration of other land-use changes in the surrounding neighborhoods, the report points out. Not long after the city rezoned the central part of Long Island City, two other large sub-neighborhoods nearby were rezoned—but the three efforts were not evaluated together.

“Currently, the unmitigated impacts that result from rezonings are not considered when new actions are proposed in neighboring areas,” the report states. “This is especially problematic in Long Island City where countless impacts have yet to be addressed, and two new projects are under review: the Long Island City Innovation Center and the Anable Basin Rezoning.”

As of early November, the latter two proposed rezonings were being reviewed separately, thus calling into question whether the city would downplay their cumulative impacts. But those two projects, with one block subtracted, now translate into the site proposed for Amazon’s new headquarters. (The subtracted block will still be part of the state’s overall review, however, sparking criticism from City Council members, as Crain’s New York Business reported.)

So that’s an argument for the so-called Generic EIS: environmental reviews that assess broader impacts in a larger neighborhood. (Other city projections can be flawed too. Public-school advocates, in a recent op-ed in Gotham Gazette, observed that “the city has consistently underestimated the real need for public schools.”)

That said, the MAS didn’t pursue its report because it foresaw Amazon, but rather because the city regularly seeks land-use changes, such as to foster affordable housing. “We need to make sure if we’re doing this kind of environmental review, we do it in the best way possible,” Goldstein said. “Rezonings are happening all over the city.”

“The big takeaway from Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City,” she said, “is that the ‘purpose and need’ for which the city initiated these rezonings was not achieved.”

How to change the city’s approach? The process has begun, according to Goldstein, as MAS starts briefing city officials and council members. “We are very engaged in the City Council Charter reform process,” she said, referring to a council-spurred review that likely will produce new ballot measures next year. The new spotlight on Long Island City—perhaps even brighter now that, in Seattle, Amazon rival Microsoft has said it will devote $500 million to affordable housing—might further influence decision-makers.

Why Brooklyn’s First Marijuana Dispensary Looks Like a Spa

Your newest weed dealer just set up shop in the shadow of the Barclays Center.

But passers-by could be forgiven for assuming that the new store at 202 Flatbush Ave. is an upscale spa. Inside the sleek, ground-floor retail space, among the nostalgia-stirring photos of old New York and vintage bottles, you’ll find weathered paperbacks on shelves next to white candles and succulent plants. Natural surfaces abound, including wood-clad walls and a handmade glass mosaic by a Bushwick artist.

With the feel of a modern-day apothecary—and the perpetual presence of a licensed pharmacist—the store is now the home of Brooklyn’s first medical-marijuana dispensary.

Citiva, a New York City-based cannabinoid medicine company, opened the store on Dec. 30—a holiday-season gift for Brooklyn’s marijuana enthusiasts that also put a bow on what was another banner year for local and national cannabis liberalization. The store will sell marijuana-based capsules, liquids and oils to people who’ve opted into the state’s medical-marijuana program after receiving a prescription from a doctor.

The spa-like feel is intentional. “The store is designed to provide the most patient-friendly experience possible,” stated Carlos Perea, chief operating officer of iAnthus, the parent company. “It serves as a welcoming and educational space for people to come in and learn about cannabis as medicine.”

But the front-lobby space is open to the public, who can learn how to enroll in the program and find a physician approved for writing prescriptions. Unlike the states from Alaska to Massachusetts that have legalized recreational marijuana, New York State’s law is still restrictive. Medical-pot dispensaries aren’t allowed to sell smokeable weed or edibles, only extracts that can be ingested via a vaporizer or inhaler.

Citiva’s store will sell offerings from established providers including PharmaCan and Etain Health, as well as their own brand of vapes, capsules and tinctures, blended for use in daytime or evening hours and with their exclusive “ratios” of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and other ingredients.

Because the state’s Department of Health dictates what lines of cannabis can be distributed to the program participants, according to Amy Holdener, vice president of Citiva’s operations in New York, the selection in Brooklyn won’t vary much from what other dispensaries in New York City have on hand—at places like Vireo Health, in Queens, and Columbia Care and Etain’s own store, both in Manhattan. However, Holdener believes Citiva’s customers will appreciate that their products are “100% pure,” with no additives. “We’re just hoping you will be able to benefit from the quality of the products we’re bringing to market,” she said.

While Brooklyn is an obvious market for Citiva’s products, finding the precise spot for the store wasn’t easy. “We’re pretty excited,” Holdener told The Bridge. “We would’ve loved to have been open even sooner,” she continued, “but it just really takes a lot of time to find the right location under the current regulations that we have.”

By law, New York’s registered medical-marijuana businesses—of which currently there are 10—shall not “locate a dispensing facility on the same street or avenue and within one thousand feet of a building occupied exclusively as a school, church, synagogue or other place of worship,” acccording to the Department of Health’s website.

An assortment of the store’s marijuana-based products, which are packaged as capsules, liquids, and oils

Citiva had to work within those parameters, while trying to optimize patient accessibility, Holdener said. Given that the Atlantic Avenue transit hub is just steps away, the storefront on Flatbush Avenue made sense as a central location, as did the busy commercial character of the immediate area.

“We want the support of the community and support of the town leaders,” she said. “We’ve incorporated work by artists from Brooklyn within the space [and] we’re hiring staff from the area as well.”

At the October meeting of Community Board 8, whose jurisdiction includes the new dispensary’s storefront, Citiva’s Director of Medical Outreach Marc Kassman spoke about its opening. Judging by the minutes, he seemed to have been met with little opposition, fielding just two questions. Kassman was asked about marketing to children, which Kassman assured Citiva won’t ever do, and the presence of a “doctor” onsite.

(Holdener clarified the minutes’ language by saying a pharmacist will be in the store assisting customers, while the company has also employed a physician who, behind the scenes, consults with other doctors about patients seeking medical marijuana.)

Citiva’s opening also garnered the approval of Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams. “I’m excited that Citiva has opened Brooklyn’s first regulated medical marijuana dispensary, providing valuable palliative care to certified patients in our borough,” Adams said in a press release. “My administration advocated hard for our borough to be part of the State’s medical marijuana program, and the long-awaited opening of this dispensary translates to quality local jobs and quality local access to critical health care.”

The Brooklyn store is the first brick-and-mortar location for the company, which until now has focused mostly on research, product development, and education initiatives. The company is also planning stores for Staten Island and two upstate locations.

The store on Flatbush could be just the first outpost of a much bigger local retail industry. New York State’s constrictions on product diversity seem destined to loosen. Since opposing weed during his first campaign for governor in 2010, Andrew Cuomo has mellowed on the subject, reviewing pros and cons of medical marijuana just a year later, reducing penalties for public possession of pot in 2012, and approving the state’s medical marijuana program in 2014.

Last year Cuomo launched a study of the impact that recreational marijuana legalization would have on New York. After its findings said the positives outweigh the negatives, he organized a workgroup to draft recreational-use legislation. That team then went on a statewide listening tour, hearing community concerns and opinions on what the laws should look like.

Following the governor’s lead, Mayor de Blasio has also reversed course when it comes to cannabis—sort of. Though he told the Daily News in May that he has “real concerns” about the seemingly inevitable dissolution of recreational-pot prohibition, he instructed the NYPD to cease arrests for public smoking, and to issue summonses instead. “He’ll put together a task force of city officials to lay the groundwork for full legalization,” the Daily News also wrote, “figuring out issues like how cops will deal with public smokers, what kind of zoning will be needed for pot dispensaries, and what types of public health campaigns the city should run about marijuana.”

Citiva plans to be ready to go with the flow. The company was acquired in 2017 for $18 million by iAnthus Capital Holdings, a publicly traded corporation that plans to expand into multiple states. Holdener said the acquisition has granted Citiva greater “depth of expertise” in the field, and enhanced its insight into marijuana legislation and sales trends across the U.S.

The company is also opening a cannabis cultivation and processing facility in Warwick, N.Y. In a statement about its construction, iAnthus wrote that the facility will “eventually support up to 125,000 sq. ft. of total cultivation and processing space,” and “enable perpetual harvesting, with an estimated yearly production of 2,400 kg of medical cannabis.”

“So as we potentially move to a recreational market,” Holdener said, “it’s going to allow [Citiva] to be poised to not only have the best product in New York, but have the best product at the best price.” However, she added, “That wasn’t our focus when we started; it’s still not our focus now. Our focus is solely on medical [marijuana], but with an eye on what looks to be happening [legislatively] in the state of New York.”

New York State residents can obtain a medical-marijuana program identification card by first consulting with a practitioner who’s registered with the Department of Health. Qualifying conditions for a patient’s participation in the program include cancer, ALS, Parkinson’s disease, HIV and AIDS, epilepsy, PTSD, chronic pain, and other ailments. After obtaining certification, a patient can register for the program online, and will later receive an ID card permitting them to buy products at state-registered dispensing facilities like Citiva.

—With reporting by Rachyl Houterman

Encore Edition: 18 of Our Favorite Stories from 2018

Brooklyn skyscrapers reached for the sky, new Italian restaurants blossomed, chic new private clubs opened, and the impact of gentrification was the talk of the town. ICYMI, here’s a sampling of The Bridge stories from 2018, some because they were most-read, others because the editor is partial to them. Happy New Year!

Why Brooklyn’s Winterfest Won’t Be Back Next Year

Yes, there has been a Santa Claus in residence here. And a few dozen elves, in the form of eager artisans selling their wares, from cozy mittens to deep-fried pickles.

But so much else about the inaugural Winterfest at the Brooklyn Museum has been a festival of frustration, including a vocal cast of aggrieved vendors, disappointed customers, contentious organizers, and appalled supporters. Winterfest won’t be back next year, at least under current management, a spokesperson for the organizers told The Bridge.

As the event plays out its final days, it’s still worth stopping by, if only to show support for the craft-market vendors who have kept their little chalets open in spite of the recriminations. But it’s also worth asking how such a winter washout could have happened in Brooklyn, which has come to consider itself a major-league event space. A few early takes:

The Hype Was Over the Top

A press release in October declared, “With visitors coming from all over the world, Winterfest will be one of the highlights of New York’s holiday season.” The event’s website still proclaims: “A world of holiday joy and wonder awaits at Winterfest Brooklyn.”

The organizers promised a veritable theme park: a shopping village of 50 entrepreneurs, rides including a snow slide called Snowzilla, an “Enchanted Tree Maze,” musical performances, a beer garden, a wine-tasting experience, and a long list of other attractions.

Salespeople at the chalet for BearHands & Buddies, a maker of mittens, scarves and accessories (Photo by Steve Koepp)

Partners in the event predicted that Winterfest would become “a marquee holiday attraction for Brooklyn,” drawing an estimated 300,000 visitors in its first year and generating an economic benefit of $15 million for the community. The event had the backing of Brooklyn Museum, which was renting out 40,000 sq. ft. of its parking lot for the festival, as well as sponsors including Delta Air Lines.

SirRoan Smiley, proprietor of herbal-goods merchant Dropping Seeds, had been optimistic about the event. “What I came to this for,” he told The Bridge, “was to be part of what was advertised: The most extravagant Christmas event in New York City.”

All of this promised wonderment may have sounded plausible to prospective customers who’ve attended winter festivals like Manhattan’s Union Square Holiday Market and Holiday Shops at Bryant Park, which offer a sensory overload of holiday sights, sounds, and merchandise. Now it would be Brooklyn’s turn.

But those festivals are operated by Urbanspace, a company that has been putting on festivals since 1972. The company behind Brooklyn’s festival, Seasonal Activation Group, is a Boston-area firm that calls itself a “worldwide leader in seasonal entertainment,” but is evidently not in the same league.

A Soft Launch, But Full Prices

When the event opened on the day after Thanksgiving, the organizers had an ambitious plan to charge admission for some of the attractions, including package deals for family outings and romantic dates. But many of the promised attractions weren’t open yet, and others were underwhelming.

Local reporters started hearing about Winterland visitors asking for refunds and describing attractions as pathetic efforts. A Bklyner reader named Julia commented, “the immersive chocolate experience is actually a cup of instant cocoa and a Tupperware of fun size Halloween candy.”

Santa was on duty at his post, but not very busy one afternoon (Photo by Lesley Alderman)

The tree maze looked like a disorganized Christmas-tree sales lot, and an exhibit on the history of Santa Claus was mostly a series of placards. Much of the perimeter was enclosed by an ungainly chain-link fence.

Visitors who had trekked a long way to the event were especially peeved. “This is a total scam and there are many angry New Yorkers,” Hannah Kim, who traveled from Bergen County, N.J., told Gothamist. She spent $75 on tickets and another $50 on food and wine. “Being that I made my husband drive for so long to go to this event, I was utterly embarrassed,” she said, calling the festival a “ridiculous event.”

The organizers started offering refunds to disappointed customers, but some of them reported difficulty reaching anyone connected with festival management. With such a difficult start, the image of Winterfest quickly pivoted from wonderland to scam event, drawing comparisons to the infamous Fyre Festival and Brooklyn’s own notorious $75-a-head pizza festival of last year.

Vendors Left in the Cold

Yet the frustration of customers paled next to that of many vendors, who were typically charged $6,200 to rent one of the little chalets where they could sell their wares. The structures suffered power outages at first, as well as leaks that soaked some of the merchandise. A rug vendor, who asked not to be named, said he had to dry out his goods several times after rainstorms.

Other vendors complained of sparse foot traffic, blaming poor logistics and and a failure by the organizers to live up to their contractual agreements to promote the event. One vendor, asking for anonymity out of concern of reprisal from the organizers, pointed out that the large gate that leads into the festival from Eastern Parkway was kept closed for the first week, with only a small walkway for passers-by to enter. Along with lack of lighting, “no one could see we were here,” she said.

Vendors, one of whom showed The Bridge the walls and wiring of his chalet, said they suffered a power outage in addition to water leaks when it rained (Photo by Patrick Smith)

Some vendors quickly dropped out. One of them, canvas-bag maker Pamela Barsky, took her complaint to the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office. “This wasn’t just disorganized, I think they had every intention of scamming everyone,” Barsky told Brooklyn Daily. “It was like kindergartners trying to set up a show.”

Barsky said she complained about the power outage directly to Lena Romanova, CEO of the company that organized the event. “As soon as I met her I complained. She then blamed me for all the problems and later sent out a letter to all other vendors saying bad things about me,” Barsky told Bklyner.

Jennifer Crosby, a spokesperson for the event, said in an email that “Winterfest is in its first year. Like in any other event of this type, our contract doesn’t guarantee specific footfall or performance to the vendors.” Crosby stated that on weekends, foot traffic has been good and the vendors have been doing well.

Several vendors who spoke with The Bridge agreed with that assessment. Some were forgiving of the shaky start, saying their expectations were tempered, given the nature of a first-time event.

Cornelia Koller, owner of Brooklyn-based COKO Jewelry, said that the customers she encountered were mostly from the neighborhood and were excited to have such an event nearby, but said the event “wasn’t quite ready” and organizers should have been better prepared.

A Reboot Helped, to Some Degree

Management of the Brooklyn Museum, seemingly appalled by the chaos of the event’s start and the rising public-relations crisis, quickly decided to force a reorganization of the event in early December.

“We are extremely disappointed that the organizers have failed to live up to their promises and we have conveyed our concerns to them,” museum management said in a statement. “Specifically, we have demanded that they make immediate changes to the overall look and feel of the event, and we have demanded that they stop selling tickets and make all attractions free of charge.”

SirRoan Smiley, proprietor of herbal-goods merchant Dropping Seeds, said his business was nearly expelled, but is sticking around for the duration (Photo by Patrick Smith)

The event was reduced in frequency as well, switching from a six-day-a-week festival to a Thursday-Sunday schedule. “Vendors complained about closing the event two days a week when they themselves asked for it to reduce costs,” event spokesperson Crosby told The Bridge in an email. “While there was power issues the first day, those issues were taken care of and resolved.” The changes seemed to boost foot traffic, vendors said.

In a statement issued to the vendors, museum spokesperson Kate Lupo said, “This has become a very challenging issue for the Museum because the organizers have failed to live up to so many of their promises and obligations that we really don’t want to associate with them.”

The only reason the museum was allowing the market to remain open, the statement said, is out of solidarity with the vendors. The museum added that the organizers had not “paid us a dime with regard to their rental obligation.”

Alleged Hardball Tactics

While the organizers sometimes seemed conciliatory about the festival’s shortcomings, they seemed acrimonious in other cases, vendors say.

Smiley, proprietor of Dropping Seeds, who was working in conjunction with the Brooklyn healing center Minka to create what they called a “healing tea temple” at Winterfest, said they had signed on for six days a week at the festival, investing $10,000 in rent and other costs.

Customers complained that the promised attractions were missing or rather sparse in their presentation (Photo by Lesley Alderman)

When the event was cut down to four days a week, however, he had “not even had a conversation” about getting a refund for the days they were promised, but suddenly received an email saying his contract would be terminated and he needed to vacate his stand or face “forced removal” if he didn’t comply.

A follow-up email from the organizers reversed the expulsion at “the request of other vendors,” but noted that Smiley—by speaking to the press about conditions at the market—had violated a clause in the rental contract and that this would be a “final warning.”

Some vendors, like this holiday-ornament shop, had trucked in large amounts of inventory to sell (Photo by Steve Koepp)

Asked about the alleged hardball tactics, Winterfest spokesperson Crosby responded: “Other vendors understand the difficulties of a first year event and that they are outside of our control. They are as disappointed as we are but they don’t go around making false and negative statement(s) to harm the event.”

Crosby alleged that several vendors spoke to the press with the purpose of sabotaging the event in hopes of getting public opinion on their side so they could get a refund from the organizers.

An Organizer With a History

Seasonal Activation Group has offices in Newton, Mass., Las Vegas, London, and Riga, Latvia, according to its website. CEO Romanova is originally from Latvia and told Bklyner that her family has been hosting holiday markets in Eastern Europe for nine years. After the shaky start in Brooklyn, she promised to make changes. “I want to make people happy,” she said. “We want it to be a memorable experience.”

Yet the firm has had at least one similarly contentious episode in the past. Seasonal Activation Group is associated with Millennial Entertainment, which since 2016 has operated a festival called Boston Winter, with more than 100 vendors. Vendors at that event complained to the Boston Globe about weak turnout, a poor physical layout, and closed concession stands.

Tucker Gaccione, owner of Boston-based The Happy Cactus, who shared a chalet at the 2017 market with two other vendors, echoed those complaints as well as what he saw as Millennial Entertainment’s adversarial way of responding to problems. Gaccione said he had “never done a market so poorly operated, that treated small business owners so badly.”

The vendor Afrodesiac Worldwide, which sells African-made goods, was one of those who stuck with the festival despite its problems (Photo by Steve Koepp)

The company that manages the seasonal festivities at Boston’s City Hall Plaza—Boston Garden Development Corp.—filed a lawsuit early this year to terminate its three-year contract with Millennial Entertainment, claiming that it’s still owed $235,000 from the first year of the agreement. Millennial, for its part, said it was ending the agreement by its own choice because Boston Garden had failed to honor terms of the contract.

The Festival’s Last Chapter

At the Brooklyn event, some vendors have kept their chalets open for business, looking forward to mild weather over the weekend, although one said that many out-of-town vendors had already packed up and shipped out. The festival will continue through next Monday, Dec. 31, according to spokesperson Crosby.

The Brooklyn Museum continued to promote the show on social media, which vendors said they appreciated, though recent posts pointedly avoided the term “Winterfest.”

And while the organizers said they’re not coming back next year, they’re not done with Brooklyn yet. “Winterfest retained legal counsel to initiate litigation and seek full recovery against parties who engaged in defamatory statements and posted anonymous stories across the web,” spokesperson Crosby told The Bridge. “More details will be announced shortly.”

Will Macy’s Total Makeover Lead to a Turnaround?

Traditionally, everything about Macy’s is big: the July 4 fireworks, the Thanksgiving Day parade, the flagship store on Herald Square. The Macy’s store in Downtown Brooklyn has been a big landmark too, with almost nine acres of floor space at its peak.

But now the Macy’s company, squeezed like so many other big retailers, is trying to reinvent itself by thinking smaller. The Cincinnati-based company, which has 650 locations, is closing some stores while shrinking and upgrading many others.

The Brooklyn store, which re-opened last month after a three-year renovation, is a prime example of the Macy’s makeover. Floor space has shrunk by about one-fourth, to 278,000 sq. ft., consolidated on just four stories and a lower level, instead of sprawling over twice as many floors.

The grand-opening ceremony last month including CEO Gennette, center, and Brooklyn civic leaders (Photo by Kent Miller, courtesy of Macy’s)

The new store environment is brighter, fresher, with more energy and less clutter. Gone are the overstocked shelves and confined spaces. In their place are more visually engaging displays designed to showcase the merchandise, not just house it. The floors have a gleaming shine, while the pillars are adorned with festive decoration.

On a recent visit by The Bridge, employees were assisting a number of customers in synchrony, more than one might expect for 11:30 a.m. on a Wednesday. Alice Avouris of Windsor Terrace was being assisted by a store employee as she attempted to buy some pants for her husband. “I like it better,” said Avouris of the new-look Macy’s. “I like the floors and the [cleaner look] makes for better ‘retail therapy.’”Avouris said she doesn’t do a great deal of online buying, and is a “picky shopper.”

While the downtown store remained open during the lengthy renovation, a confusing interior layout was less than welcoming. Now Macy’s hopes shoppers will come streaming back. “We are proud to present our customers with an updated store environment, enhanced merchandise offerings and an elevated sense of customer service,” said Kizzie Tunson, vice president and store manager, in a statement. “We anticipate everyone in the community will find a reason to come in and take a second look at their local Macy’s.”

The Hotel Collection, on the store’s lower level, offers housewares from stylish pots and pans to luxurious sheets with high thread counts (Photo by Steve Koepp)

The store has played a prominent role in Brooklyn history. It started small, a 25-foot-wide storefront that opened in 1865 by a 22-year-old Bavarian immigrant named Abraham Abraham and his friend Joseph Wechsler. In 1893, the Straus family bought Weschler’s interest in the company and was renamed Abraham & Straus. The current complex was built in 1873 and later expanded in 1929 and 1947.

In its heyday, A&S became a hub of Brooklyn cultural life, with an estimated 70,000 customers a day, and it became the flagship of an 18-store chain. In 1995, however, the parent company converted all the A&S stores to better-known national brands like Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s.

As part of the current shrinking process, Macy’s has unloaded some of its extensive real estate. It sold the top five floors of the Brooklyn store (and a nearby parking garage) for $270 million to the developer Tishman Speyer, which is crowning the complex with a ten-story office tower to become a “creative hub” called The Wheeler.

The apparel sections of the store offer mini-boutiques, like this one for Adidas (Photo by Steve Koepp)

“If your store is too big and your dollars per square feet are too low and you can’t lease the space to someone else, then you’ve got to hive off a floor,” Macy’s CEO Jeff Gennette told the Wall Street Journal last month for a story about the company’s downsizing. “If we were building stores today, we’d build them smaller,” he said.

What happened to make these radical adjustments necessary? As recently as 2015, Macy’s had operating margins hovering over 10% and sales growth was still positive. But an almost 15% reduction in gross profit since 2015 has had Macy’s scrambling for answers. Since then, the brand has lost more than 3.4 million customers, according to a report produced for Macy’s by the research-and-consulting firm GlobalData.

Online giants like Amazon certainly have played a part in this, according to Neil Saunders, managing director of retail at GlobalData. Icons ranging from Sears to Toys “R” Us have been brought down in the so-called retail apocalypse. But as much as Amazon is portrayed as the big bully who is single-handedly killing brick and mortar stores, in this case it simply isn’t true.

Sergio Arias, a frequent Macy’s customer from Howard Beach who said the renovation process had been a deterrent from shopping, was back and said the store now looks “very different” (Photo by Patrick Smith)

Most of the customer defection Macy’s is seeing is to other brick-and-mortar retailers, particularly the discounters TJ Maxx, Nordstrom Rack and Kohl’s, who have all taken a larger share of Macy’s customer base than Amazon, according to GlobalData.

“They did not evolve fast enough,” said Saunders of Macy’s performance. “And of lot of the stores look like they did in the 1970s and 1980s, which is not what customers want now.” Stores bloated with inventory, coupled with large and expensive floor space, made finding products or assistance from employees difficult. This caused customers to find the stores “uninspiring” and “dull,” according to the report.

Another problem in Macy’s strategy, said Saunders, was in promoting too many other brands rather than developing their own. When those name brands become commodities and customers shop primarily based on price, the competition is easily won by the likes of TJ Maxx, who built their entire business on the discount model.

The store on Fulton Street was once the flagship for the Abraham & Straus chain (Photo courtesy of Macy’s)

In the renovated Brooklyn store, shoppers can see Macy’s answer to that challenge, especially in the housewares department on the lower level. The proprietary Hotel Collection—“It’s all the luxury you could want”—has everything from dishes to coffeemakers to linens, all developed for Macy’s.

Frequent special sales were another problem for Macy’s, “getting into a cycle of constantly discounting stock to sell it through. This got the customer accustomed to only purchasing when a product was discounted,” Saunders said. The redesigned Brooklyn store was dotted with signs advertising the idea of “one low price.”

Scaffolding still partially blocks the view of the Art Deco edifice as its makes its transition into a mixed-use complex called The Wheeler (Photo by Patrick Smith)

While growing the house brands are part of Macy’s strategy, the company is simultaneously bringing in eye-catching popular brands. The ground floor now has an expanded, 18,000-sq.-ft. cosmetics department, with name-brand counters including Dior, Bobby Brown, Kiehl’s, Philosophy, and Benefit Cosmetics. The same floor offers name-brand handbags, a LensCrafters outlet, and an At Your Service center.

The second floor is the men’s department, with brand additions including Super Dry, Armani Exchange, and Lacoste. On the third floor is women’s read-to-wear (featuring DKNY, Rachel Roy, and Juicy Couture) and a new shopping service called MyStylist @ Macy’s. The fourth floor has children’s wear and intimate apparel.

Will the new look turn the company around? Macy’s beat their early fiscal 2018 financial predictions, with CEO Gennette saying in a call to investors that “we are still early on in our journey, but as I look at the progress we’ve made on merchandising, on our strategic initiatives, the re-engineering of our marketing machine … I feel good about the work that’s underway and optimistic about Macy’s Inc. future.”

The company may be benefiting from a tailwind, at least at the moment. “Macy’s has done some good things and some smart things with their stores,” said Saunders. “The slight issue is that the consumer economy is very robust. How much of this growth is due to Macy’s and how much is due to the market?”

In Brooklyn, at least, Macy’s has a fresh face and a new start. Said Alice Avouris, the shopper from Windsor Terrace: “It does matter how a store looks.”

Backers of the BQX Say Amazon Helps Prove Their Case

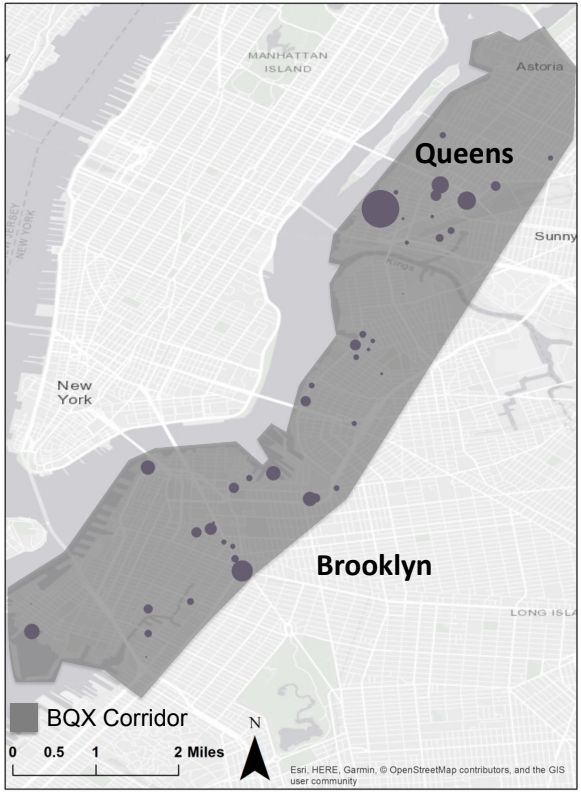

The proposed Brooklyn Queens Connector (BQX) streetcar system has been moving forward at a crawl for nearly three years, sometimes even appearing to be permanently stalled. Along the way, ambitions have been tempered. In August, Mayor de Blasio announced a new plan in which the rail system would be shorter (11 miles, down from 16), pricier ($2.73 billion, up from $2.5 billion), and later (running by 2029, instead of 2024).

The progress so far, along with debate about the plan’s worthiness, hasn’t left Brooklyn and Queens residents holding their breath for that low-cost, scenic ride from Gowanus to Astoria.

But then along came Amazon and its plans to spend $2.5 billion to create an office complex for 25,000 workers in Long Island City, right along the BQX’s proposed route. Amazon’s plan has delivered a see-what-we-mean moment for BQX supporters, who contend that commercial and residential development along the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront will make the rail system an essential transit link.

A rendering of proposed BQX lines crossing between the boroughs on the Pulaski Bridge over Newtown Creek (Image courtesy of Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector)

Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector, a non-profit organized to support the streetcar proposal, issued a statement Thursday making their case: “Amazon’s decision to open a Long Island City campus underscores just how essential a role the BQX will play in delivering workers—many living in areas sorely underserved by quality mass transit—to jobs and workforce development opportunities along the corridor, which will be home to more commercial space than the downtowns of Los Angeles, Philadelphia or Boston by 2029.”

To buttress the point, the BQX group released a new analysis of future commercial-property development along the route. Office space within a mile of the BQX corridor is expected to grow by more than 50%, or 20 million sq. ft., over the next decade, said the report, conducted by the BJH Advisors real-estate firm for the BQX group. The corridor could be home to 70,000 new jobs, including the 25,000 at Amazon’s campus, as the spillover effect of Amazon’s investment stimulates the economy around it, the report said.

The BQX already has the substantial support of the business community, including the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership and the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. “I’m sure many Brooklynites will be commuting to Long Island City to work at Amazon,” chamber CEO Hector Batista told The Bridge for a story on the company’s arrival. “So this is actually a great time to get to work on projects like the BQX light rail in order to help us continue to grow our local talent and economy.” The BQX group is chaired by Jed Walentas, CEO of Two Trees Management, developer of the multibillion-dollar Domino Sugar factory redevelopment site in Williamsburg.

A mockup of the proposed streetcar on display a year ago in the Brooklyn Navy Yard (Photo by Steve Koepp)

Yet the project still faces major obstacles in terms of logistics and cost, including the argument that the money would be better spent on other kinds of transportation projects, like bus lines. The proposed streetcar would be built by a public-private partnership and paid for partly through the increased tax revenue collected from rising property values along the route. But it would still need about $1 billion from the federal government, the mayor’s office acknowledged this year.

Some elected officials and other opponents, however, think the BQX would be a costly distraction from focusing on improving existing transit. Earlier this month, City Council Member Carlos Menchaca, who represents Red Hook and Sunset Park, ripped the plan as a “terrible” idea in a hearing at City Hall. Speaking to transit chief Andy Byford, the council member declared: “Your visionary plan is in conflict, I think, with this idea that no one likes except for developers and can have an impact … on your plan if so much energy is going from the [government ] agencies into this plan.”

In another twist, Queens Borough President Melinda Katz, who supports the BQX plan, said earlier this month that Amazon should help pay for it. “A substantial and meaningful investment by Amazon that helps ensure the feasibility of [the BQX],” she said, “would be a fair investment into its new home and a welcome opportunity for a good corporate neighbor.”

Of course, using the Amazon development in support of the BQX begs the question of whether the Amazon deal is a good one for the city. City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and several Queens elected officials have blasted the lack of community input in the agreement, which was brokered by the governor and the mayor, and the $2 billion in public subsidies provided for it. “We got played,” declared Johnson at a public hearing on the Amazon deal.

For Brooklyn’s part, however, the borough’s civic leaders made a spirited bid to lure the so-called HQ2 and several now say that having it right next door is a lucrative consolation prize for the area’s economy.

The corridor along the proposed route of the BQX, where supporters predict rapid growth of commercial office space (Map courtesy of Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector)

The Rescue of a Brooklyn Startup Kitchen Falls Apart

Just as the cake seemed baked, it has fallen apart. Nearly 200 displaced food-oriented businesses were preparing to return to the former Pilotworks community kitchen in Brooklyn when they were told this week that an agreement to reopen the facility had collapsed, leaving the startup businesses locked out during the busiest season of the year.

Culinary entrepreneur Adam Melonas, who had agreed to take over the shuttered incubator, told the former Pilotworks members in an email Tuesday that the deal was off, blaming conditions in the kitchen that do not “match the extremely high standards by which our company is known to operate.”

Melonas, founder of Chew, a food innovation lab in Cambridge, Mass., had planned to rebrand the kitchen as Nursery. “This news is heartbreaking for me personally, as I know it is for many of you,” Melonas wrote in the email. “[W]e paused our lives and risked everything, in belief of this community and our ability to change the lives and companies of each and everyone of you.”

Acumen Capital Partners, which entered the agreement for the Melonas firm to take over the Brooklyn facility, did not return a request for comment from The Bridge. Acumen bought the old Pfizer building on Flushing Avenue for $26 million in 2011 and turned it into a center of culinary innovation, with the startup incubator occupying a portion of the massive, eight-story building.

The New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYC EDC), which backed the launch of the incubator in 2015 with $1.3 million in funding, told The Bridge in a statement, “Unfortunately, negotiations between the landlord and the prospective operator were not successful.”

When it was up and running, the entrepreneurs at the facility were focused primarily on creating foods, condiments and drinks with a level of specificity that is rarely seen in major brands (Photo courtesy of FoodWorks)

City Council Member Robert Cornegy, Jr., who represents the district that includes the Pfizer building, and who publicly supported the initial legislative funding for the space, told The Bridge in an email that he is “frustrated by Nursery’s decision to abandon their plans to take over the Pilotworks space.” He added: “This news so close to the Christmas holiday is extremely disappointing.”

Launched as Brooklyn FoodWorks, the facility got off to a roaring start, but has had a troubled management history. The original proprietors were soon bought out by food entrepreneurs Nick Devane and Mike Dee, who raised $15 million in venture capital and went on an aggressive expansion to other cities under the brand name Pilotworks.

Then in mid October, the owners abruptly closed the facility, citing an inability to raise more funds. The sudden move left the fledgling food-and-beverage companies out in the cold. The timing was particularly bad for their businesses, coming at the beginning of the holiday season.

Less than two months later, however, their spirits rose when Melonas, who has been described as a Willy Wonka of culinary innovation, agreed to take over the Brooklyn facility. In an email to Pilotworks members, he said his company was “honored to open our doors to this wonderful and inspiring community of makers.”

Several of the small-business owners who received that message told The Bridge they were looking forward to getting back to work in the bustling kitchen. They hoped to salvage their fourth-quarter revenues, and were eager to cook side-by-side with other members who’d banded together to help keep each other afloat in the wake of the Pilotworks debacle.

Back in October, the startup kitchen was abruptly closed, with resident companies getting only a few days to clear out (Photo by Michael Stahl)

Then came this week’s email from Melonas. “[W]e are devastated to be the bearers of this news,” he wrote. “We made every effort possible to give this new undertaking the best possible chance of success. We believe deeply in the mission of all of your businesses and the mutual support you have shown one another continues to be an inspiration to us all.”

Former Pilotworks members who had anticipated a return to the kitchen under the Nursery banner expressed frustration and disbelief over the latest development. “I don’t even know what to say. I have no idea how this went so wrong,” said Anke Albert, who owns Anke’s Fit Bakery, in a text to The Bridge.

Anjali Bhargava, the founder of Bija Bhar, which produces a turmeric-based elixir, said in an email, “I was counting on this. Feels like a big blow after I had gotten my hopes up and made plans accordingly.” Bhargava added that she’d like to know at some point soon if the situation is “resolvable or if we really need to give up on being back in the space.”

Veggie Grub proprietor Chef Rootsie said in a succinct text to The Bridge, “Will the madness ever end?”

At a Pilotworks event, an array of products launched at the facility demonstrated its diversity (Photo by Angelica Frey)

“[O]ur hearts continue to break for these producers,” said Cheryl Clements, founder and CEO of PieShell, a food- and beverage-focused crowdfunding platform, in an email to The Bridge. Her organization recently launched a campaign to raise money for the former Pilotworks members. “This is not what they needed to hear with the holidays all around us.”

In his email breaking the news, Melonas said that the NYC EDC, which had interviewed several prospective suitors to take over the space leading up to the Nursery agreement, would contact them to “discuss alternative solutions.” In its statement, the EDC said it “prides itself on fostering economic opportunities across New York City and will continue to offer aid to affected food businesses.”

The EDC has reached out to the displaced Pilotworks members “to reemphasize our commitment to independent food and beverage makers” and to offer financial assistance and other resources.

“We look forward to our continued collaborations with membership to ensure they have the best opportunities to succeed in the shared kitchen and incubator space,” the statement said.

In spite of all this disappointment, stakeholders in this troubling Pilotworks saga may have dodged a bullet with Nursery’s evacuation. After reporting two weeks ago that Melonas and his team would take over the space, The Bridge received several emails from former Chew employees, who called Melonas a difficult and deceptive manager.

The Bridge spoke with two of them, a man and a woman who didn’t want their names used because they feared retaliation from Melonas, they said. They discussed their time at Chew a few years ago, when the company had around 20 employees. According to both, Melonas carried himself in the office like a dictator, talking down to them during all-hands staff meetings each morning. “He was really big on shaming,” the woman said.

Originally launched as Brooklyn FoodWorks, the incubator had 16 workstations for entrepreneurs to develop new products (Photo courtesy of FoodWorks)

Describing Melonas as someone whose “ego can’t fit in the building,” she said that Melonas demanded a lot of employees, but then often didn’t fulfill his own commitments. “He would keep us there till 11 o’clock at night, redoing stuff that he wanted to send to potential clients,” the woman said, recalling that Melonas distributed paychecks weeks later than expected and failed to meet such financial promises as the reimbursement of relocation costs.

The Bridge reached out to Nursery’s public-relations firm for comment on these allegations, but received no response.

The male source confirmed the woman’s stories, and said Melonas would frequently “mislead clients” about the productivity and goings on in the company. In a press release written when Nursery was set to occupy the Pilotworks space, Chew boasted of a client list consisting of “the world’s largest and most influential food and beverage companies.” With Chew, the companies had “created more than 1,400 products.”

The female former employee told The Bridge those numbers are “extremely inflated to say the least,” and the male former employee concurred. “What we did all day was make iteration after iteration of the same product over and over again,” he said. “I think it’s like a dozen products that actually have been on a store shelf … and of those at least six have been discontinued already.”

The two sources said about 40 former Chew workers keep in touch in a private Facebook group and email, likening the collective to a support group. “After going through an experience like that with someone, you’re like war buddies,” the male source said. “We’re all pretty tight.” A barrage of Chew company reviews posted by anonymous current and former employees on Glassdoor, a job-finder website, paint a similar picture of the company’s corporate culture.

Given the reports that the Pilotworks brass had a track record of failed businesses, and may also have unwisely spent company funds, such details about Nursery raise questions about the vetting process in finding occupants for the old Pfizer building’s abandoned kitchen. In an email, the EDC said bringing in Nursery was the call of building owners Acumen Capital Partners, as the EDC was “not involved with Chew’s discussions or agreement with the landlord.”

Council Member Cornegy said he hasn’t given up on the space as a food incubator, which in its brief lifespan had generated dozens of new products and companies. “I remain committed to helping find a suitable tenant for the space so we can restore this meaningful resource for the many small business owners who relied on it.”

Downtown Brooklyn Teams up to Fight Street Crime

Shoppers have become used to crowds and commotion in retail stores during the holidays, but nothing like what happened last month at the Target store in Downtown Brooklyn. Six men in their 20s, one carrying a large knife, pursued a 44-year-old man through the store. After a brief skirmish, the older man shot one of his pursuers in the chest, fatally wounding him. Both the shooter and the man wielding the knife were charged with criminal possession of a weapon, among other crimes.

The Nov. 7 killing at the store in the City Point complex along the Fulton Mall was just one of several incidents of gang-related gunplay in the area in recent months. Suggesting a pattern of violence in Brooklyn’s busiest hub, the shootings prompted Borough President Eric Adams in recent weeks to convene with police, elected officials and business leaders to confront the issue.

Earlier this week, amid the busiest shopping days of the year, Adams and several officials gave a press conference to announce crime-prevention measures they’re putting in place. Adams began by describing the unique nature of Downtown Brooklyn, one of the most mixed-use neighborhoods in the city, including a retail district, courthouses, schools, and high-rise residential buildings.

“It is a very complicated area,” Adams said. “We have a number of courts. Family courts are located here. (The) Supreme Court is located here. Civil courts are located here. We have many parolees, probation officers, all come down to the Downtown area. Witnesses being interviewed by the District Attorney’s offices. And we have a lot of schools,” Adams said.

“But all of that on top of the fact that this is the shopping district of Brooklyn, it makes it extremely complicated to make sure that safety is … treated as the No. 1. priority. It is the prerequisite to any type of prosperity,” Adams concluded.

At Borough Hall earlier this week, from left: Melinda Alexis-Hayes of the District Attorney’s office, the NYPD’s Jeffrey Maddrey, Borough President Eric Adams, Downtown Brooklyn Partnership President Regina Myer, and Randy Williams of the city’s Department of Correction (Photo by Patrick Smith)

To be sure, crime in the general area is just a vestige of what it used to be. In the 84th Precinct, which includes Fulton Mall as well as such neighborhoods as Brooklyn Heights and Dumbo, the number of robberies last year was just 127, down 93% from 1990, when the statistic hit 1,908.

Even so, gunplay in the Fulton Mall area raises high-level concerns not only because of the vast crowds of innocent bystanders, but because the headlines have the potential to discourage shoppers, which was even the case decades ago, when Brooklynites were more inured to violent crime.

Now the economic stakes are even higher, since billions of dollars have been invested in new residential, office, and retail developments, including such City Point destinations as Century 21 and the DeKalb Market Hall. Commercial rents on Fulton Street reached $326 per sq. ft. last year, among the highest in the U.S.

What’s problematic in terms of crime, Adams said, is the major presence of court systems, which draw alleged criminals and parolees, as well as their associates and gang rivals.

In a shooting on July 13 near the Gap Factory Outlet on Fulton Mall, three people were wounded, including the intended target and two bystanders. On Aug. 1, gunfire apparently sparked by a sidewalk argument rang out at MetroTech Center at 11:15 a.m., prompting office workers to take shelter; no was was injured. On Oct. 1, multiple shots were fired just a block from Borough Hall in mid afternoon, wounding at least two of the teens involved in the altercation.

The October episode prompted Adams to call for a collaboration of Brooklyn leaders to search for solutions. “The Downtown Brooklyn community was deeply impacted today by gunshots fired in broad daylight, the third such incident in effectively as many months,” he said in a statement. “Young people were in the immediate vicinity of this shooting, as were members of my office.”

Police investigate the scene of a shooting in October in which teens were wounded (Image via NBC News)

At a press conference later in October, Adams attributed the outbreak of shootings to gang members and other criminal defendants visiting courts and parole offices. In investigating the incidents, police found guns stashed at multiple Downtown sites, as if in preparation for a beef with rivals. “People who were on their way to court,” Adams said, “appeared to have hidden guns on construction sites or other locations.”

At this week’s press conference, Adams and other officials said they are putting in place several new measures, including the increased use of security cameras, heavier policing, and sharing of information among departments.

“We did have a few incidents earlier in the year,” said the NYPD’s Jeffrey Maddrey, commanding officer of Patrol Borough Brooklyn North, “but we were able to put more resources down, increase the visibility of the patrol officers, increase our intelligence gathering capacity to understand what was going on and why we were having this phenomenon.” All of the shootings, Maddrey said, were gang-related.

Regina Myer, president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, said that her organization is providing increased information from its affiliates—the partnership manages the MetroTech Business Improvement District as well as the Fulton Mall Improvement Association—in the form of new and enhanced security cameras as well as increased collaboration with the NYPD.

Representatives from both the city’s Department of Correction and the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office stated that they were relaying more information to NYPD when potential “problem” individuals would be in the area, hoping to head off any potential confrontations before they start.

All parties professed confidence that their new, comprehensive approach to identifying potential threats would pay dividends.

“This is a safe place because of the coordination we have put in place,” Adams said. “And to those who believe they want to come downtown and create any form of havoc: It is not going to happen in Downtown Brooklyn.”

A Whimsical Shop Where Every Picture Tells a Story

The Risk Gallery & Boutique in Bushwick has been called “one of the most Instagrammable places in New York,” but just seeing it on a smartphone doesn’t do it justice. Once you set foot inside, it’s like entering a dreamland of color, playfulness and whimsy. From pink, princess-like dresses to unicorn headbands and watermelon-shaped handbags, the space is a trove of eclectic treasures.

In the dressing room, delighted customers have been known to scribble testimonials on the walls. “This store makes me feel like I could fight dragons and look glamorous while doing it,” read one note.

The boutique’s owner, Lindsay Risk, said her goal was to replicate Barbie’s closet. She considers the space to be “an adult playground” that strives to combine the experiences of visiting an art gallery, shopping for high-end vintage items, and attending a party. “It’s a happy place,” Risk told The Bridge. “It’s where people want to come and spend all day. I’d say 90% of the people that come in here say, ‘Can I live here?’”

The proprietor, Lindsay Risk, outside the original Bushwick shop she opened in 2015 (Photo by Katie Warren)

This month, after a brief hiatus, Risk’s business re-opened in new, larger space at 205 Central Ave., about a mile southeast of her previous location. Because the boutique is on the ground floor of a new residential building, she was able to design the store from scratch, including a lower level that does multiple duty as a studio and event space. “I’m very happy. I love the new space,” she said.

Besides operating the retail store, Risk works as a personal stylist and provides garb for magazine fashion shoots and TV shows including The Deuce and The Americans. “I’d say 30% of my business is costume for HBO, for Showtime, and for some independent stuff,” she said.

Risk’s new space landed with a splash of notoriety even before it opened. Risk, with help from friends and family, painted the sidewalk outside the store in a black-and-white chessboard pattern, just as she had at her previous location. While some neighbors, especially kids, seemed to take delight, at least one neighbor called 311 to complain. The city’s Department of Transportation threatened a $250 fine and a local TV news crew showed up to chronicle the controversy. Risk is circulating a petition to defend it.

Risk’s carefully curated vintage ware is flamboyant, elegant, and sometimes both (Photo by Katie Warren)

Risk opened her original Bushwick gallery-boutique in 2015 after working in the nightlife industry for a decade. The Michigan native, lifelong artist and graduate of Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) worked for the Gerber Group, the operator of swanky hotel bars like the Whiskey Blue.

After quitting her job and moving to Bushwick with her husband, she worked on her paintings in a rented studio and earned money selling clothes on consignment in neighborhood shops and painting their holiday window displays. It was a frigid day in February when she realized she should open her own store.

This is the latest installment of a periodic feature on The Bridge, focusing on retail stores in the borough

“I was freezing cold and walking down the street, and every one of these stores had all my clothes in the window and my art on the window,” she recalled. “I said to my husband, ‘We’re never going out to dinner ever again, we’re going to eat Chinese food every day, and I’m going to open my own store. I’m just going to do it.’” She had set aside some money from her corporate work as well.

Even so, she had found a calling well-matched to her last name. Retail businesses, especially the brick-and-mortar kind, have struggled in recent years, battered by rising rents and competition from online shopping. Many of the new retailers in Brooklyn have been national chain stores rather than indies, and Bushwick has been no exception.

But Risk says she has succeeded because her business is more than just a retail store. “It’s difficult to break even in retail,” she said. “It’s so hard, especially with Amazon taking over the world. However, this store is an experience, and it’s a destination experience. So that’s the only reason I think I’m surviving—and expanding.”

Before opening the boutique, however, Risk had no idea what it would be like. “I really had no idea how to run a retail store,” Risk said. “I knew how to open and run a bar.”

Studying the Business

To learn the ropes, Risk asked if she could work for a friend who owned a children’s store on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. “I asked her, ‘Can I just, like, intern for two months to learn how to run a store?’” Risk said.

She learned that although the basic business principles were the same, there was actually a vast difference between her past and future industries, especially in terms of the clientele. “It’s just a totally different animal because in Brooklyn, one day I have hipsters, the next day I have men that want suits, and the next day I have moms with children,” Risk said. “It was very difficult, in the beginning, to shop for [the store].”

Every set piece in the store has little surprises tucked here and there, including family and celebrity photos (Photo by Lesley Alderman)

Eventually, she embraced an expansively eclectic process of gathering merchandise. Pieces in the store come from artists in New York, Italy, Bali, and beyond. She knows the stories of every item for sale, many of which were sourced from her own family, including clothes from her mother’s closet, hats from her grandmother, and a neon sign from a store her father used to own in Detroit.

“Growing up, I always loved Barbies. I was an only child and my mom was working, so she would send me to my playroom,” Risk said. “She was a model and she was married five times. Sometimes we’d shop at Salvation Army; sometimes we’d shop at Barneys. I learned how to dig and I learned what was quality, too.”

Doing double duty as stylist and mannequin, Risk struck a pose in her original Bushwick store (Photo courtesy of Risk Gallery & Boutique)

Risk’s paintings line the walls of the store, while the shelves carry jewelry and clothing from her travels to Indonesia. She supports other artists by stocking their handiwork, including sunglasses made by a student at FIT and jewelry made by an artist in Italy. She features an artist-in-residence as well, currently Taylor Hengesbach of Ette Art.

Risk’s knack for finding unique pieces has served her well in another side of her business: personal styling. In August, she was slammed with people looking for outfits for the Burning Man festival in Nevada. She finds the one-on-one styling sessions particularly meaningful. “I love doing the styling,” she said. Some women come to the store who have suffered personal trauma or setbacks, she said, “or they feel fat or they feel awful, and we just try to make you feel good and make you feel positive about yourself.”

As part of that good vibe, Risk works hard to banish any of the usual vintage-store mustiness. “I’m a germaphobe. Everything here is nicey-nicey-nice,” she said. Her advice to vintage-clothing shoppers is to avoid falling for just a cute look, and spend time inspecting the quality of the garment. “Make sure the stitching is proper” and check for stains and missing buttons, she said. Anything that says “union made” on the label tends to be of higher quality and holds its value better than other garments, Risk said.

The shopkeeper says she’s going to court to defend the art she painted on the sidewalk (Photo by Steve Koepp)

Just as with her wares, the proprietor seems emotionally invested in her sidewalk artwork, which she notes was created with non-slip paint, specially made for concrete. While the alternating black-and-white squares remind some passers-by of Alice in Wonderland, which took place upon a large chessboard, to Risk it’s also a symbol of the hard work and smart moves needed to survive in business. Risk said she plans to go to court to defend it, armed with her petition.

The gallery and boutique are open Friday through Sunday from noon to 8 p.m. and Tuesday through Thursday by appointment, which can be made by emailing lindsay@rosybleu.com.

A shopper checks out a vintage look assembled with items from the store (Photo by Steve Koepp)

Amazon in Brooklyn: Why the Bid Didn’t Quite Measure Up

Did Brooklyn ever really have a chance at winning the new Amazon campus?

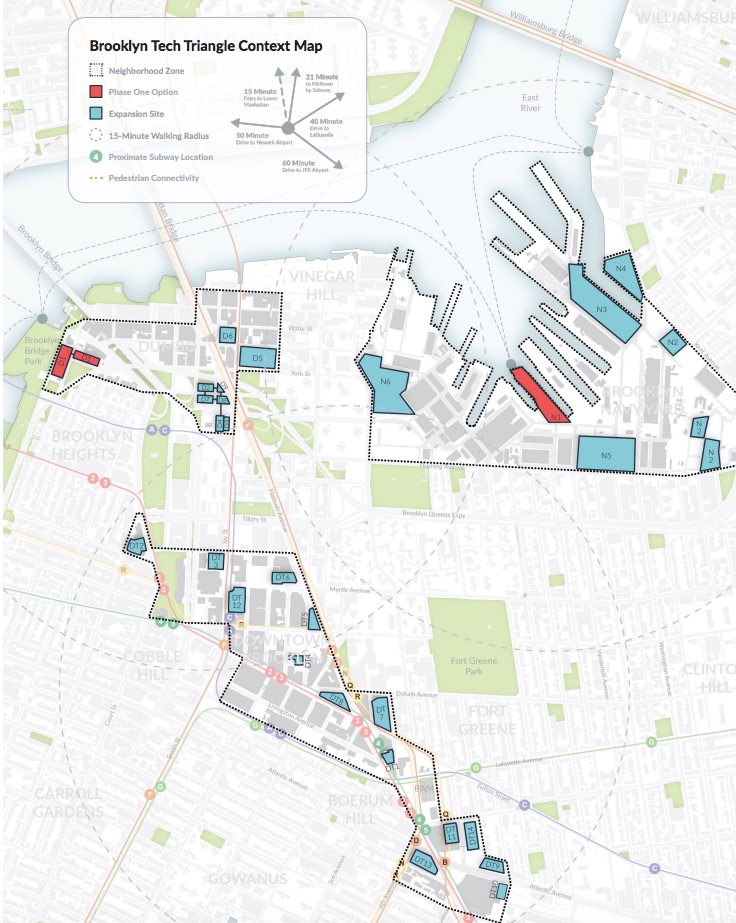

The Brooklyn Tech Triangle may have many assets, including residential space, creative companies, food, and educational institutions, but a comparison of the bids presented to the Seattle-based behemoth looking to house at least 25,000 workers shows that Long Island City, the company’s choice, had some distinct advantages.

Not only did Long Island City offer space above a subway station for the first tranche of workers, that building, at One Court Square, was closer to a move-in than two sites proposed in Brooklyn: the Panorama complex (formerly the Watchtower headquarters) at the edge of Dumbo and Fulton Ferry, and Dock 72 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

One Court Square was presented as cheaper than Panoroma and competitive with Dock 72. Also, future office space—Amazon seeks a total of 4 million sq. ft.—would cost less in Long Island City, with more opportunity for contiguous sites.

The city/state bid included a map showing sites available in the Brooklyn Tech Triangle, including Downtown, Dumbo, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, with the Phase 1 buildings in red (Map courtesy of the NYC EDC)

Still, boosters of the Brooklyn bid pulled out the stops, even mocking up an image with Amazon supplanting the former Watchtower sign on the complex formerly owned by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and in the process of conversion by its new owners, Columbia Heights Associates.

The city-and-state bid to Amazon, released last night by the New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYC EDC) after a public information request from Politico, even modified Milton Glaser’s iconic “I ❤️ New York” logo by substituting Amazon’s smiling-arrow symbol for the heart image. The documents emerged less than two days before the first City Council hearing regarding plans for a new Amazon campus.

Brooklyn < LIC

While Brooklyn offered a cost advantage over both Midtown West and Lower Manhattan, the other two city neighborhoods in the package, Long Island City still offered logistical and price advantages. For example, One Court Square, long known for its anchor tenant Citigroup, was said to offer “net illustrative rent” of $46 per sq. ft.*

Amazon would get 12 months of free rent on a 20-year lease and, yes, NYC EDC also presented an image of that building topped by the Amazon logo.

In Brooklyn, Dock 72 at the Navy Yard, under construction by Boston Properties/Rudin and scheduled for occupancy next year, was presented as renting for $43 per sq. ft. But that 610,000-sq.-ft.space, despite offering an outdoor half basketball court and four outdoor terraces, is far from a subway, relying on shuttles and a future ferry. It too offered 12 months of free rent.

The Dumbo-adjacent Panorama site, 25-30 Columbia Heights, is under conversion and “offers a prominent signage opportunity atop a Brooklyn icon,” but also lacks direct subway access. The rent was said to be $59 per sq. ft., with six months free on a 20-year lease for the 772,000-sq.-ft. complex.

Real-state firms that proposed buildings for the first phase of occupancy were said to have executed term sheets with NYC EDC, thus agreeing to refrain from leasing their space until this year in order to hold it open for a prospective Amazon move-in.

Building out the Campus

Beyond that, for the further buildout, several Long Island City sites—including some (but not all) that Amazon chose—were presented as costing between $24 and $49 per sq. ft., a relatively wide range.

Brooklyn didn’t quite measure up. While five potential expansion sites at the Brooklyn Navy Yard were said to cost $43 per sq. ft., the total available space (2.6 million square feet) would have been insufficient for Amazon, even combined with Dock 72.

Ditto for the eight potential expansion sites in Dumbo, offering 2.54 million sq. ft. and renting for at least $54 per sq. ft. (Note: before Amazon decided to split its purported HQ2 into two sites, including Crystal City, Va., the sites contesting for HQ2 were presenting a potential 8 million sq. ft.)

The bid touted the recently expanded NYC Ferry, while promoting the Brooklyn-Queens Connector (BQX) as “a state-of-the-art streetcar with the potential to connect over 400,000 residents to major job hubs along the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts”—but, of course, its future remains uncertain.

“Land Use Action Required”

Brooklyn’s bids offered many creative proposals for using space under development, or planned for it. The eagerness to welcome Amazon meant that a good number of site owners were open to a change in use and thus zoning, typically a deliberative process involving community input and City Council approval, but not in this case. After all, Empire State Development, Gov. Cuomo’s economic-development authority, has been prepared to override city zoning to ease the process, as it plans to do in Queens.

In Dumbo, more than 1 million sq. ft. would have come from converting the 85 Jay complex, a former Jehovah’s Witnesses parking lot expected to house residential space, into office use, albeit renting for $64 per sq. ft. The document notes “land use action required,” indicating the need for that state override.

The city, which pitched four sites in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens, included this rendering of Amazon’s logo atop One Court Square in Long Island City (Rendering courtesy of the NYC EDC)

Downtown Brooklyn, offering much transit and adjacent residential space, offered more than 9 million sq. ft. in 14 buildings, with rents said to be between $49 and $59 per sq. ft. Notably, the bid indicated a willingness to ensure that two planned buildings, 565 Fulton St. and 625 Fulton St., would include office space, with “land use action required.”

Moreover, the bid discloses an ambitious plan for construction at, and near, the Pacific Park project, all associated with the address 590 Atlantic Ave.. That’s currently home to retail outlets P.C. Richard & Son and Modell’s, at the intersection of Flatbush and Fourth avenues.

The four prospective towers offered to Amazon included one site at the northeast flank of Barclays Center, long known as B4 of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, which is expected to start construction next year and house 810 apartments. It too would have required “land use action.”

Another would be the 1.14 million-sq.-ft. tower (or towers) planned for the P.C. Richard/Modell’s parcel, long known as Site 5 of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area. While that site has been approved for office space, the developers aim to augment it by shifting the bulk of the never-built tower approved for the Barclays Center plaza across the street, which also would require “land use action.”

Finally, the bid discloses ambitious plans to build towers, apparently already permitted by current zoning, over the Atlantic Center mall. The bid describes two sites, one with 990,000 sq. ft. and the other, with 1.84 million sq. ft. (which likely means two towers). Such towers were once to be designed by Frank Gehry, the original Atlantic Yards architect.

While Brooklyn’s business and civic leaders appeared to put a lot of effort and creativity into the bid, and Brooklyn’s tech community touted its abundance of talent, the Long Island City bid tended to offer cheaper and more readily available space for the early and later phases of the project. But in the end, given Brooklyn’s current issues with high costs and gentrification, the prospect of having Amazon at arm’s length may offer more tempered benefits and challenges.