How the Borough President Is Essentially Backing 80 Flatbush

While he would chop one tower's height 39%, Adams proposes just a 12% cut in bulk, plus benefits like a new subway entrance

Borough President Adams recommends that the two-part school building between the towers more than double in height to accept some bulk subtracted from the taller tower (Rendering courtesy of Alloy Development)

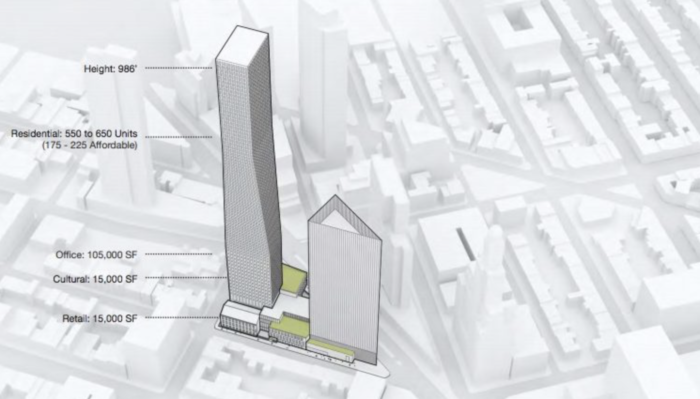

When Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams weighed in last week on the hotly contested, two-tower 80 Flatbush project, what drew most of the attention was his proposal to chop the height of the larger tower. Adams recommended cutting the project’s taller tower from the proposed 986 feet to 600 feet, a downsizing of 39%. That change would respond to one criticism of the project–that it would be out of scale, vastly higher than even the nearest skyscraper, the 610-ft. 333 Schermerhorn St., also known as The Hub.

Officially, Adams checked the box marked “disapproval with conditions” in his recommendation to the City Planning Commission. But he was sending a notably different message than the one delivered by Brooklyn Community Board 2’s nearly unanimous vote against the ambitious plan, which would combine market-rate and affordable housing, office space, two schools, retail shops, and cultural space in a tight, 1.4-acre site.

What the borough president’s dramatic height-reduction proposal obscured is a modest 12% reduction in floor area, leaving the complex far bulkier than the standard in rezoned Downtown Brooklyn nearby and still approaching 1 million sq. ft. in floor space. The site is within the Special Downtown Brooklyn District, which was designated to create a transition between high-rise Downtown Brooklyn and the row houses of nearby neighborhoods like Boerum Hill.

The taller of 80 Flatbush’s two towers would be cut to the height of The Hub, at right, according to Adams’s recommendation

In the 37-page document Adams submitted to the planning commission, he proposed that some bulk be shifted to an intermediate building currently planned to contain a new elementary school, a replacement for Khalil Gibran International Academy, and a shared “gymnatorium.” That building would grow from 130 feet to 300 feet in height. The shift in bulk, detailed in the full recommendation, was not mentioned in the borough president’s press release last Friday.

The project has been proposed by Dumbo-based Alloy Development in partnership with the New York City Educational Construction Fund (ECF), which partners with developers in order to construct schools with no direct capital outlay.

Subtracting Density, Then Adding It

Besides the project’s proposed height, another big point of contention is its density, a measure of how much floor space (and thus people and their activities) will be packed into a building complex. The Alloy/ECF proposal asks for a rezoning to nearly triple the allowed Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which assesses bulk as a multiple of the lot size, from 6.5 to 18. Critics, including Assembly Member Jo Anne Simon and State Senator Velmanette Montgomery, have called that rezoning “unprecedented.” (See our previous coverage.)

The borough president’s recommendation did not quantify his suggested cut in density, but his document includes the data for making such a calculation. Adams proposed a different zoning classification, with an initial FAR of 10, but then cited various bonuses for affordable housing, a subway-station improvement, school space, and a community facility. The result: an effective FAR of 15.8. (Adams’s office confirmed this reporter’s calculations.)

Adams’s proposal would make the schools building significantly taller

That exceeds the standard of 12 FAR, if one includes a bonus for affordable housing or a plaza, set in the 2004 Downtown Brooklyn rezoning. It also exceeds the ratio of 15 FAR allowed in the recent spot rezoning for apartments and office space at 141 Willoughby. City Council Member Stephen Levin, whose District 33 includes the 80 Flatbush site, earlier this year suggested to The Bridge that the Willoughby project was more clearly located in Downtown Brooklyn rather than at its margin.

It’s unclear whether Adams’s proposed reduction would diminish the amount of residential space in the building–with some 700 proposed market-rate units and 200 affordable ones–or commercial space. The borough president’s office, when queried, commented that the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP, “is ongoing.”

The borough president’s recommendations, like the Community Board’s vote, are non-binding. The City Planning Commission, which held a hearing June 13 (see video), will vote by late July to approve, modify, or disapprove the application. After that, the City Council, with Levin as a crucial voice, will decide. Adams’s proposal seemingly leaves room for Levin to recommend further cuts.

Adams Aims for “Perfect Combination”

The borough president made several other recommendations, including an emphasis on affordable-housing units big enough to accommodate families, a new subway entrance at the corner of State Street and Flatbush Avenue, and a rat-mitigation strategy for the construction site. To help achieve the cut in height and bulk, he proposed decoupling part of the development from ECF funding, asking the city Department of Education to fund the new elementary school–and thus re-injecting public capital for the project.

In recognition of the project’s impact on residential, low-rise State Street, Adams recommended shifting the Flatbush Avenue tower’s loading dock from State to Schermerhorn Street, and that the elementary school entrance be moved to Third Avenue from State Street.

“My goal is to realize the perfect combination of addressing the need to create affordable housing–the most critical issue facing Brooklyn–while simultaneously taking into consideration the history of the neighborhood,” stated Adams, who’s pursuing the mayoralty in 2021, in his press release. “The voices of Boerum Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, and adjoining communities are reflected in these recommendations, which I hope will be thoughtfully considered as this ULURP application moves through the process.”

Critics Call It a Start

Howard Kolins, president of the Boerum Hill Association (BHA), gave initial praise to Adams’s “thoughtful recommendations,” saying his “recognition of the Boerum Hill and Fort Greene communities is the first step to a better solution.”

That said, Adams rejected the BHA’s call for a single, as-of-right tower (which wouldn’t necessarily include affordable units), and only the high school. Also, putting a 600-foot tower on Third Avenue represents an acceptance of significantly more bulk on the south side of Schermerhorn, otherwise home to a row of buildings rising no higher than 140 feet.

Looking east along Schermerhorn Street, where the taller 80 Flatbush tower would be situated down the block on the right side of the street. The Hub is the tallest building at left (Photo by Norman Oder)

Ben Richardson, a founder of the Block 80 Flatbush Towers campaign and a board member of the Fort Greene Association, said he was encouraged by elements of Adams’s proposal but warned “there has been no financial transparency” regarding “the real cost to the taxpayers of this project measured against the actual value of the public benefit.”

While the developer claims $230 million in public benefit, critics suggest the developer would reap far more value from the air rights granted by the rezoning as well as access to the city’s borrowing power in raising money for the project. No independent entity has assessed those numbers.

Developer Unruffled, at Least Partly on Board

Alloy, lauded for smaller projects like 1 John Street in Brooklyn Bridge Park, sounded unperturbed by Adams’s recommendation. “We appreciate that the Borough President took the time to review our application and that his decision acknowledges the pressing need for the public benefits included in our proposal,” said CEO Jared Della Valle in a statement.

“We also appreciate that the decision reflects the widespread support we’ve received for the project, both in the neighborhood and citywide,” he added. “The consensus among those supporters is that building in Downtown Brooklyn along Flatbush Avenue and across from one of the largest transit hubs in the city to deliver much-needed affordable housing, two public schools and cultural space makes 80 Flatbush a model for thoughtful urban planning and development.”

A letter from Alloy and the ECF appended to Adams’s recommendation indicates that the developer is already on board with various proposals made by the borough president, including larger affordable units, hiring local and minority-owned businesses, and meeting environmental standards. That letter does not address issues like height and bulk, presumably subject to later negotiations.

The developer agreed to negotiate a Community Benefits Agreement–a concept that has worked nationally but was extremely controversial with the Atlantic Yards project–to address quality of life issues, including construction logistics, noise and dust, and pest control.

Looking at Affordability

The project is proposed in two phases, with a 561-foot-tall tower along Flatbush Avenue, with market-rate residential and office space, plus the schools building. Phase two would involve the larger tower, which includes market-rate housing, affordable housing, and office space, plus reuse of two historic buildings.

The height of the taller tower would be cut nearly 40% under Borough President Adams’s proposal (Image from Educational Construction Fund presentation)

Adams would like some of the affordable housing to be included in the first phase, suggesting “it might be possible to re-evaluate the funding arrangements.” He also would accept fewer affordable units to achieve more family-sized units, with two- and three-bedroom units.

With the current estimated square footage for below-market units, the average unit size would be closer to one bedroom. If at least half of the affordable units contain two or more bedrooms, by this reporter’s estimate–which Adams’s office deemed reasonable–there could be 165 to 170 apartments.

The housing will be affordable to residents with an average of 60% of Area Median Income (AMI), which is considered low-income. However, because some units for seniors could have rents set as low as 30% of AMI, the target average of 60% AMI could still be met by including some middle-income units; the developers’ letter to Adams pledges no households over 130%.

Though the project is in Community Board 2, Adams suggested that nearby residents of Community Board 6, who live in the New York City Housing Authority’s Gowanus Houses and Wyckoff Gardens, as well as households with children who attend local schools, should be considered among those who get local preference for 50% of the affordable units.

The Transit Issues

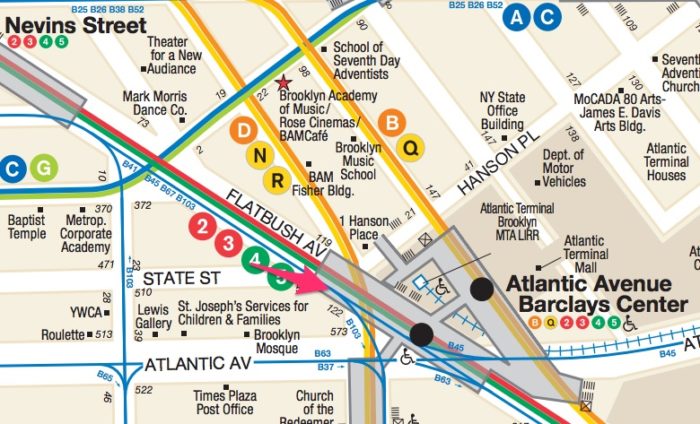

The project has been supported as an example of transit-oriented development, given its proximity to multiple subway stations, including Brooklyn’s biggest subway hub. Adams suggested that, given that the developers would save money by not being required to build the typical amount of interior car-parking, the public should get an additional benefit in exchange.

He proposed public access directly to Atlantic Terminal, specifically the Brooklyn-bound 2/3 subway track at the Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center subway. The developers could construct an access way to the platform level, and would “at minimum, fund engineering investigation and construction drawings” for a passageway situated at the northern corner of State Street at Flatbush Avenue. The developer “would be expected to fund a portion of such improvement,” he wrote, leaving some wiggle room.

The Borough President proposes a new subway entrance (see red arrow) from 80 Flatbush to the 2/3 Brooklyn-bound track at the Atlantic Ave.-Barclays subway (Image adapted from MTA neighborhood map)

Questions About Timing of Benefits

At the City Planning Commission hearing, most public commenters supported the project, including a top policy advisor to Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen. They argued for the public benefits as well as the general impact of increased supply on moderating rents. (By contrast, the first public hearing overwhelmingly included project opponents, and the second leaned negative.)

None of the commissioners sounded disapproving in their comments, but they posed pointed questions. “This is a very, very complicated project,” said Commissioner Anna Hayes Levin, who complimented the developers on the clarity of their presentation. “You’re being asked to accomplish a whole lot of things that result in this having to be a very large project.” (Among those things: public-school seats, partly because of the unintended consequences of the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, which was aimed primarily to add office space but instead delivered thousands of apartments.)

“This is a zoning designation that … only exists in this particular neighborhood in Lower Manhattan,” said Levin, referring to the area around the meeting site. “So that will be breaking a barrier for Brooklyn.” She asked why the project’s initial benefit was schools, with the affordable housing coming in the second phase. “A project of this scale, we know it’s likely that it will take twists and turns, and probably be something quite different by the time it gets built. But we need the affordable housing now,” she asserted.

Jennifer Maldonado, executive director of ECF, responded that the school-development agency owns only about 23% of the site. “In order for those schools to be built and paid for, we need the revenue from the first piece,” which includes the market-rate housing. She said the project’s development agreement obligates Alloy to build the affordable units as well, and would provide a separate letter describing that. (It hasn’t been previously made public.) Alloy’s Della Valle added that “there’s a huge financial incentive for us to get to that aspect of the project.”

Questions About Scale and Demand

Levin asked Regina Myer, president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership (and former head of the Department of City Planning’s Brooklyn office), if she could respond to the Boerum Hill Association’s point that the site was meant to be transitional. “From the perspective of the folks in Boerum Hill,” she asked, “how can we feel right about the planning decision that locates such scale so close to them?”

“I think the overriding principle is the location on Flatbush Avenue,” responded Myer, emphasizing the Downtown Brooklyn edge of the site and noting the new high-rise construction along that artery, including mixed-use projects like 300 Ashland. “This is really our last location to develop at that scale.”

Commissioner Larisa Ortiz noted that Community Board 2, in its disapproval of the project, pointed to the numerous, still-vacant new apartments in Downtown Brooklyn. “Are you seeing higher rates of vacancy?” she asked. “We see reports that rents are going down, and concessions are being made.”

Myer responded that “four projects of considerable scale came online at once” this year. “I have not heard from the development side, concerns about absorption,” she said, using the industry term for new apartments getting rented or purchased. (At a conference in May, experts suggested that the Downtown Brooklyn apartment surplus may be easing, as The Bridge reported.) Ofer Cohen, a commercial real-estate broker who is the new chair of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, said that that pipeline of new projects would slow down in two years, so this one would meet demand.

Two Broader Perspectives

At the hearing, a resident of State Street across from the project site, said he supported 80 Flatbush, despite the inconvenience of construction. “People rarely support major developments before they happen,” he said. “But when done well, they are loved by the communities of the future.”

At a previous hearing, sponsored by the borough president, one project opponent warned about the course of the debate, calling the ambitious proposal “a classic highball-lowball tactic,” he said. “When my little daughter asks for three cookies, hoping for two when she should get one, she still gets one.” So far, the second cookie, at minimum, seems achieved.